Over the last two weeks, the media has speculated on who is likely to be the next governor of the Reserve Bank of India(RBI). If media reports are to be believed Arvind Panagariya, the vice-chairman of the NITI Aayog, seems to be leading the race.

Arundhati Bhattacharya, the chairperson and the managing director of the State Bank of India, is also in the race. The factor going in her favour is that she is a woman, and RBI has had no woman governor till date. The factor going against her is that the merger of the State Bank of India with its subsidiaries has been initiated, and the government is keen that she completes that. Newsreports suggest that the government is even ready to give her an extension so as to ensure that she is able to complete the merger.

Until sometime back Rakesh Mohan, a former deputy governor of the RBI, was also deemed to be in the race. But given that he recently called the Mumbai-Ahmedabad bullet train project useless, his chances of becoming the next RBI governor, despite being qualified for it, are rather dim.

As has been seen in the past, the Modi government is rather touchy about any sophisticated criticism. That was one of the points that went against the outgoing RBI governor Raghuram Rajan, who was seen to be as outspoken. Given this, the government is unlikely to appoint another similar individual. Former deputy governor Subir Gorkarn along with one of the current deputy governors Urjit Patel, are also said to be in the race. And given the government’s tendency to appoint bureaucrats to the RBI governor’s post, one cannot rule out any of the senior bureaucrats in the finance ministry.

Of course, the speculation will continue, until the government announces the next RBI governor, which has to happen soon, given that Rajan’s term ends in early September 2016.

One of the theories that has been put forward over coffee table conversations (at least among people who have such conversations while having coffee) is that the next RBI governor will be someone who is close to the government and in the process do what the government wants him or her to do.

This basically means that the next RBI governor will do the Modi government’s bidding and in the process cut the repo rate. Repo rate is the rate at which the RBI lends to banks. The hope is that once the RBI cuts the repo rate banks will cut their lending rates as well. In the process people will borrow and spend and economic growth will return. This is something that the finance minister Arun Jaitley, has been demanding for a while now.

While the interest rate mechanism is not so straightforward, but then that doesn’t stop people from talking and hoping. Remember, we are talking about coffee table conversations here.

In fact, a similar logic was offered when D Subbarao was made the RBI governor in 2008. Subbarao at that point of time was the finance secretary. He was also in line to be the next cabinet secretary, given his seniority. As the finance secretary he directly reported and worked with the then finance minister, P Chidambaram.

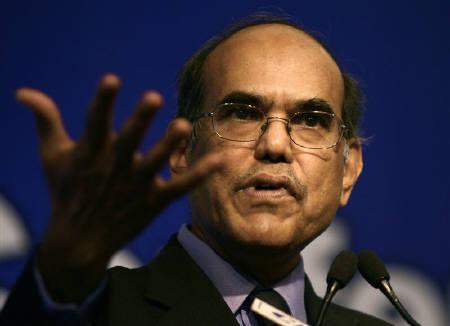

At that point of time the then government, like Jaitley is now, had been demanding lower interest rates. But the then RBI governor YV Reddy had not obliged. When Reddy’s second term came to an end in 2008, Subbarao was appointed to succeed him.

This led people to conclude that given that the government was appointing the current finance secretary as the RBI governor, he would bat for the government. In the past, finance secretaries have been appointed as RBI governors. This includes YV Reddy as well as Bimal Jalan, who was the RBI governor between 1997 and 2003, before Reddy took over.

In Subbarao’s case, it was the first case of the finance secretary directly becoming the RBI governor. In all the earlier cases, there had been breaks. Subbarao recounts this in his new book Who Moved My Interest Rate? – Leading the Reserve Bank of India Through Five Turbulent Years: “Y.V.Reddy, my predecessor, had a formidable reputation for standing his ground with the government. The commentariat said that my familiarity with, and sympathy for, the government’s point of view would help repair that strained relationship between the ministry of finance and the Reserve Bank. Others thought that my allegiance to the ministry of finance would make me more pliable and I would dilute the independence of the Reserve Bank. Some even suggested that I was being dispatched to implement the government’s agenda from within the Reserve Bank.”

People who analysed along these lines forgot that Reddy like Subbarao after him, had also been an IAS officer. Hence, using the logic, even he should have been pliable and could have been made to do things that the government wanted him to. But that did not turn out to be the case and he did what he thought was right for the country.

Subbarao in his book goes on to write: “The only bit [of all the analysis happening on his appointment] that troubled me was doubts about my credentials and the suspicion that I would compromise the autonomy of the Reserve Bank. I was aware too that the only way I could counter those doubts and suspicions, and establish my credibility, was by demonstrating my professional integrity in all that I said and did, which would inevitably take time.”

Rest assured that if Panagariya or Bhattacharya are appointed as the RBI governor, a similar sort of logic of them being close to the government, will be offered. But the thing to remember is that in the past many RBI governors have come from bureaucracy and done the right thing.

There are multiple reasons for it. One is that they have their legacy to think about. Second, the past RBI governors have set high standards and given that the new RBI governor needs to stand up to that. Look at what happened at the Election Commission, after TN Seshan cleaned it up. Booth capturing and violence (though not totally) have become a thing of the past.

Third, the RBI governor’s job is typically the last high-profile government job, an individual will take on, and hence, he need not oblige the government and keep it in good humour. (Manmohan Singh is an exception to this). Fourth, the RBI governor needs to do the right things, if he or she wants to be taken seriously by the financial markets.

Given these reasons, the next RBI governor, whoever he or she is, is likely to do the right things, than just bat for the government.

The column originally appeared in Vivek Kaul’s Diary on Equitymaster on July 27, 2016