Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

Economists and analysts have turned bearish on the future of the rupee, over the last couple of months. But very few of them predicted the crash of the rupee. Among the few who did were,SS Tarapore, a former deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of India, and Rajeev Malik of CLSA.

Tarapore felt that the rupee should be closer to 70 to a dollar. As he pointed out in a column published in The Hindu Business Line on January 24, 2013 “With the inflation rate persistently above that in the major industrial countries, the rupee is clearly overvalued. Adjusting for inflation rate differentials, the present nominal dollar-rupee rate of around $1 = Rs 54 should be closer to $1 = Rs 70. But our macho spirits want an appreciation of the rupee which goes against fundamentals.”

Rajeev Malik of CLSA said something along similar lines in a column published on Firstpost on January 31, 2013. “The worsening current account deficit is partly signalling that the rupee is overvalued. But the RBI and everyone else are missing that clue,” he wrote. The current account deficit is the difference between total value of imports and the sum of the total value of its exports and net foreign remittances

What Tarapore and Malik said towards the end of January turned out to be true towards the end of May. The rupee was overvalued and has depreciated 20% against the dollar since then. The question is why did most economists and analysts not see the rupee crash coming, when there was enough evidence available pointing to the same?

One possible explanation lies in what Nassim Nicholas Taleb calls the turkey problem (something I have talked about in a slightly different context earlier). As Taleb writes in his latest book Anti Fragile “A turkey is fed for a thousand days by a butcher; every day confirms to its staff of analysts that butchers love turkeys “with increased statistical confidence.” The butcher will keep feeding the turkey until a few days before thanksgiving. Then comes that day when it is really not a very good idea to be a turkey. So, with the butcher surprising it, the turkey will have a revision of belief—right when its confidence in the statement that the butcher loves turkeys is maximal … the key here is such a surprise will be a Black Swan event; but just for the turkey, not for the butcher.”

The Indian rupee moved in the range of 53.8-55.7 to a dollar between November 2012 and end of May 2013. This would have led the ‘economists’ to believe that the rupee would continue to remain stable against the dollar. The logic here was that rupee will be stable against the dollars in the days to come, because it had been stable against the dollar in the recent past.

While this is a possible explanation, there is a slight problem with it. It tends to assume that economists and analysts are a tad dumb, which they clearly are not. There is a little more to it. Economists and analysts essentially feel safe in a herd. As Adam Smith, the man referred to as the father of economics, once asserted, “Emulation is the most pervasive of human drives”.

An economist or an analyst may have figured out that the rupee would crash in the time to come, but he just wouldn’t know when. And given that he would be risking his reputation by suggesting the obvious. As John Maynard Keynes once wrote “Worldly wisdom teaches us that it’s better for reputation to fail conventionally than succeed unconventionally”.

An economist/analyst predicting the rupee crash at the beginning of the year would have been proven wrong for almost 6 months, till he was finally proven right. This is a precarious situation to be in, which economists/analysts like to avoid. Hence, they tend to go with what everyone else is predicting at a particular point of time.

Research has shown this very clearly. As Mark Buchanan writes in Forecast – What Physics, Meteorology and the Natural Sciences Can Teach Us About Economics “Financial analysts may claim to be weighing information independently when making forecasts of things like inflation…but a study in 2004 found that what analysts’ forecasts actually follow most closely is other analysts’ forecasts. There’s a strong herding behaviour that makes the analysts’ forecasts much closer to one another than they are to the actual outcomes.” And that explains to a large extent why most economists turned bearish on the rupee, after it crashed against the dollar. They were just following their herd.

There is another possible explanation for economists and analysts missing the rupee crash. As Dylan Grice, formerly an analyst with Societe Generale, and now the editor of the Edelweiss Journal, put it in a report titled What’s the point of the macro? dated June 15, 2010 “Perhaps a more important thought is that we’re simply not hardwired to see and act upon big moves that are predictable.”

A generation of economists has grown up studying and believing in the efficient market hypothesis. It basically states that financial markets are largely efficient,meaning that at any point of time they have taken into account all the information that is available. Hence, the markets are believed to be in a state of equilibrium and they move only once new information comes in. As Buchanan writes “the efficient market theory doesn’t just claim that information should move markets. It claims that only information moves markets. Prices should always remain close to their so called fundamental values – the realistic value based on accurate consideration of all information concerning the long-term prospects.”

What does this mean in the context of the rupee before it crashed? At 55 to a dollar it was rightly priced and had incorporated all the information from inflation to current account deficit, into its price. And given this, there was no chance of a crash or what economists and analysts like to call big outlier moves.

Benoit Mandlebrot, a mathematician who spent considerable time studying finance, distinguished between uncertainty that is mild and that which is wild. Dylan Grice explains these uncertainties through two different examples.

As he writes “Imagine taking 1000 men at random and calculating the sample’s average weight. Now suppose we add the heaviest man we can find to the sample. Even if he weighed 600kg – which would make him the heaviest man in the world – he’d hardly change the estimated average. If the sample average weight was similar to the American average of 86kg, the addition of the heaviest man in the world (probably the heaviest ever) would only increase the average to 86.5kg.”

This is mild uncertainty.

Then there is wild uncertainty, which Dylan Grice explains through the following example. “For example, suppose instead of taking the weight of our 1000 American men, we took their wealth. And now, instead of adding the heaviest man in the world we took one of the wealthiest, Bill Gates. Since he’d represent around 99.9% of all the wealth in the room he’d be massively distorting the measured average so profoundly that our estimates of the population’s mean and standard deviation would be meaningless…If weight was wildly distributed, a person would have to weight 30,000,000kg to have a similar effect,” writes Grice.

Financial markets are wildly random and not mildly random, like economists like to believe. This means that financial markets can have big crashes. But given the belief that economists have in the efficient market hypothesis, most of them can’t see any crash coming.

In fact, when it comes to worst case predictions it is best to remember a story that Howard Marks writes about in his book The Most Important Thing (and which Dylan Grice reproduced in his report titled Turning “Minimum Bullish” On Eurozone Equities dated September 8,2011). As Marks writes “We hear a lot about “worst case” projections, but they often turn out not to be negative enough. I tell my father’s story of the gambler who lost regularly. One day he heard about a race with only one horse in it, so he bet the rent money. Halfway around the track the horse jumped over the fence and ran away. Invariably things can get worse than people expect. Maybe “worse case” means “the worst we have seen in the past”. But it doesn’t mean things can’t be worse in the future.”

Disclosure: The examples of SS Tarapore and Rajeev Malik were pointed out by the Firstpost editor R Jagannathan in an earlier piece. You can read it here)

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 26, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Dylan Grice

Rupee debacle: UPA should stop blaming gold for screw up

“How do I define history?” asked Alan Bennett in the play The History Boys, “It’s just one f@#$%n’ thing after another”.

But this one thing after another has great lessons to offer in the days, weeks, months, years and centuries that follow, if one chooses to learn from it.

Finance minister P Chidambaram and other fire fighters who have been trying to save the Indian economy from sinking, can draw some lessons from the experience of the Mongols in the thirteenth and the fourteenth century.

The Mongol Empire at its peak, in the late 13th and early 14th century, had nearly 25 percent of the world’s population. The British Empire at its peak in the early 20th century covered a greater landmass of the world, but had only around 20 percent of its population. The primary reason for the same was the fact that the Mongols came to rule all of China, which Britain never did.

In 1260 AD, when Kublai Khan became King, there were a number of paper currencies in circulation in China. All these currencies were called in and a new national currency was issued in 1262.

Initially, the Mongols went easy on printing money and the supply was limited. Also, as the use of money spread across a large country like China, there was significant demand for this new money. But from 1275 onwards, the money supply increased dramatically. Between 1275 and 1300, the money supply went up by 32 times.By 1330, the amount of money in supply was 140 times the money supply in 1275.

When money supply increases at a fast pace, the value of money falls and prices go up, as more money chases the same amount of goods. As the value of money falls, the government needs to print more money just to keep meeting its expenditure. This leads to the money supply going up even more, which leads to prices going up further and which, in turn, means more money printing. So the cycle works. That is what seems to have happened in case of Mongol-ruled China.

Gold and silver were prohibited to be used as money and paper money was of very little value as the various Mongol Kings printed more and more of it. Finally, the situation reached such a stage that people started using bamboo and wooden money. This was also prohibited in 1294.

What this tells us is that beyond a certain point the government cannot force its citizens to use something that is losing value as money, just because it deems it to be so. By the middle of the 14th century, the Mongols were compelled to abandon China, a country, they had totally ruined by running the printing press big time.

There is a huge lesson here for Chidambaram and others who have been trying to put a part of the blame on the fall of the rupee against the dollar because of our love for gold. The logic is that Indians are obsessed with buying gold. Since we produce almost no gold of our own, we have to import almost all of it. And every time we import gold we need dollars. This sends up the demand for dollars and drives down the value of the rupee.

This logic has been used to jack up the import duty on gold to 10%. But as Jim Rogers told the Mint in an interview “Indian politicians…suddenly blamed their problems on gold. The three largest imports to India are crude oil, gold and cooking oil. Since they can’t do anything about crude and vegetable oil, the politicians said India’s problems were because of gold, which, in my view, is totally outrageous. But like all politicians across the world, the Indians too needed a scapegoat.”

The question that no politician seems to be answering is, why have Indians really been buying gold, over the last few years? And the answer is ‘high’ inflation. As we saw in Mongol ruled China, it is very difficult to force people to use something that is losing value as money. And rupee has constantly been losing value because of high inflation.

High inflation has led to a situation where the purchasing power of the rupee has fallen dramatically over the last few years. And given that people have been moving their money into gold. As Dylan Grice writes in a newsletter titled On The Intrinsic Value Of Gold, And How Not To Be A Turkey “Now consider gold. In ten years’ time, gold bars will still be gold bars. In fifty years too. And in one hundred. In fact, gold bars held today will still be gold bars in a thousand years from now, and will have roughly the same purchasing power. Therefore, for the purpose of preserving real capital in the long run, gold has a property which is unique in comparison with everything else of which we know: the risk of a loss of purchasing power approaches zero as one goes further into the future. In other words, the risk of a permanent loss of purchasing power is negligible.”

And this is why people are buying gold in India. Gold is the symptom of the problem. Take inflation out of the equation and gold will stop being a problem, though Indians might still continue to buy gold as jewellery. But creating ‘inflation’ is central to the politics of the Congress led UPA. Now that does not mean that people need to suffer because of that? Especially the middle class. As M J Akbar put it in a column in The Times of India “Gold is the minor luxury that a confident economy purchases for its middle class. The cost of gold imports has become a problem only because the economy has imploded.”

Nevertheless people need to protect themselves against the inflationary policies of the government. “Historically, people have understood money’s intrinsic value when they have been forced to, when alternative monies have been rendered unfit for purpose by persistent debasement,” writes Grice.

In ancient times Kings used to mix a base metal like copper with gold or silver coins and keep the gold or silver for themselves. This was referred to as debasement. In modern day terminology, debasement is loss of purchasing power of money due to inflation.

Given this, people will continue to buy gold. The buying may not show up in the official numbers because a lot of gold will simply be smuggled in. A recent Bloomberg report quoted Haresh Soni, New Delhi-based chairman of the All India Gems & Jewellery Trade Federation as saying “Smuggling of gold will increase and the organized industry will be in disarray.”

And other than leading to a loss of revenue for the government, it might have other social consequences as well. As Akbar wrote in his column “If we are not careful we might be staring at 1963, when finance minister Morarji Desai imposed gold control to save foreign exchange. Desai, and a much-weakened prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, could issue orders and change laws but they could not thwart the Indian’s appetite for gold, even when he was in a much more abstemious mood half a century ago. All that happened in the 1960s was that the consumer turned to smugglers. From this emerged underworld icons like Haji Mastan, Kareem Lala and their heir, Dawood Ibrahim. India has paid a heavy price, including the whiplash of terrorism.”

Maybe the new Dawood Ibrahims and Haji Mastaans are just about starting up somewhere.

The piece originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 20, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

As yen hits 100 to US$, get ready for more currency wars

Vivek Kaul

Ushinawareta Nijūnen or the period of two lost decades for Japan(from 1990 to 2010) might finally be coming to an end. Or so it seems.

And Japan has to thank Abenomics unleashed by its current Prime Minister Shinzo Abe for it. Abe has more or less bullied the Bank of Japan, the Japanese central bank, to go on an unlimited money printing spree, until it manages to create an inflation of 2%.

The Japanese money supply is set to double over a two year period. And all this ‘new’ money that is being pumped into the financial system, will chase an almost similar number of goods and services, and thus drive up their prices. Or so the hope is.

The target is to create an inflation of 2% and get people spending money again. When prices are rising or are expected to rise, people tend to buy stuff, because they don’t want to pay a higher price later (This of course is true to a certain level of inflation and doesn’t hold in the Indian case where retail inflation is greater than 10%). As people go out and shop, it helps businesses and in turn the overall economy.

In an environment where prices are stagnant or falling, as has been the case with Japan for a while now, people tend to postpone purchases in the hope of getting a better deal. The situation where prices are falling is referred to as deflation.

In 2012, the average inflation in Japan was 0%, which meant that prices neither rose nor they fell. In fact, in each of the three years for the period between 2009 and 2011, prices fell on the whole. This has led people to postpone their consumption and hence had a severe impact on Japanese economics growth. To break this “deflationary trap”, Shinzo Abe and the Bank of Japan have decided to go on an almost unlimited money printing spree.

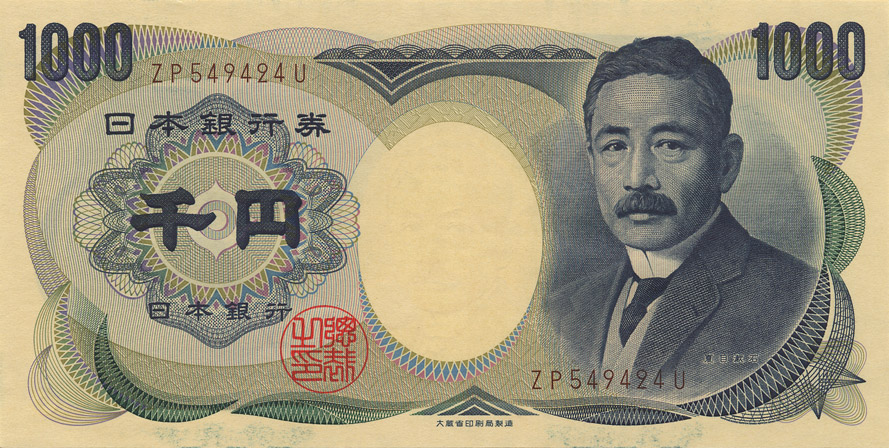

A major impact of this policy has been on the Japanese currency ‘yen’. As more yen are created out of thin air, the currency has weakened considerably against other major currencies. One dollar was worth around 78 yen, on October 1, 2012. Yesterday, yen weakened beyond 100 to a dollar for the first time in four years. As I write this one dollar is worth around 101.1 yen.

This weakening of the yen has helped Japanese businesses which have a major international presence spruce up their profits. As the news agency Bloomberg reports “The weaker yen helped Mazda, Japan’s fifth-largest car company, post a profit of 34 billion yen for the fiscal year that ended March 31, compared with a loss of 107.7 billion yen the previous year. A one-yen change against the dollar, euro, Canadian dollar and Australian dollar has a 9.1 percent impact on Mazda’s operating profit…That compares with 4.7 percent at Fuji Heavy Industries Ltd, which makes Subaru cars, and 3.1 percent at Toyota.”

When yen was at 78 to a dollar, a Japanese company making a profit of $1 million internationally would have made a profit of 78 million yen. Now with the yen at 101 to a dollar, the same company will make a profit of 101 million yen, which is almost 29.5% more.

This increase in profit it is hoped will also encourage Japanese companies to pay their employees more. Albert Edwards of Societe Generale writing in a report titled Thoughts on Asia will a yen slide trigger an EM currency crisis? 1997 redux dated April 17, 2013, cites a survey which suggests that Japanese companies may be short on labour. “This suggests that Prime Minister Abe will indeed get his way on a rapid return of wage inflation to boost consumption,” writes Edwards.

And this boost in consumption will get the Japanese economy going again. So does that mean Japan will live happily ever after? Not quite.

As the Japanese central bank prints more and more yen, the returns from Japanese government bonds are expected to go up. As Edwards writes “if the market really believes that it is committed to the 2% inflation target (and I certainly do), then Japanese bond yields(returns) will quickly attempt a move above 2%.” In early April the return on a ten year Japanese government bond was at 0.45% per year. Since then it has risen to around 0.69% per year.

And this can lead to a major crisis in Japan. If returns on existing bonds go up, the government will have to offer a higher rate of interest on the new bonds that it issues to make them interesting enough for investors.

As Satyajit Das writes in a research paper titled The Setting Sun – Japan’s Financial Miasma “Higher interest rates will increase the stress on government finances. Even at current low interest rates, Japan spends around 25-30% of its tax revenues on interest payments. At borrowing costs of 2.50% to 3.50% per annum, two to three times current rates, Japan’s interest payments will be an unsustainable proportion of tax receipts.”

Now that’s just one part of it. If the government has to spend more of the money than it earns towards interest payments that means there will be less left for meeting other expenditure. So it will either have to borrow more or ask the Bank of Japan to print more money to finance its expenditure, given that there is a limit to the amount of money that can be borrowed. Either option doesn’t sound good. Das estimates that Japan’s gross government debt will reach around 250-300% of its gross domestic product by 2015, a very high level indeed.

Also as things stand as of now it looks like the Bank of Japan will have to finance a major part of Japanese government expenditure in the years to come by printing money. As Dylan Grice wrote in an October 2010, Societe Generale report titled Nikkei 63,000,000? A cheap way to buy Japanese inflation risk “Japan’s tax revenues currently don’t even cover debt service and social security, persistent and growing fiscal burdens. Therefore, once the Bank of Japan is forced into monetisation of government deficits, even if only with the initial intention of stabilising government finances in the short term, it will prove difficult to stop. When it becomes the largest holder and most regular buyer of Japanese government bonds, Japan will be on its inflationary trajectory.” And this is not an inflation of 2% that we are talking about.

The yen weakening against other international currencies is making Japanese exports more competitive. A Japanese exporter with sales of a million dollars in early October, would have made 78 million yen (when one dollar was worth 78 yen). Now the same exporter would make 101 million yen.

The weakening yen allows Japanese exporters to cut their prices in dollar terms and become more price competitive. If a price cut of 20% is made, then sales will come down to $800,000 but in yen terms the sales will be at 80.8 million yen ($800,000 x 101). This will be higher than before. Also a cut in price might help Japanese exporters to increase total volumes of sales.

The trouble of course is that this will hit other major exporters like South Korea, Taiwan and Germany. As Michael J Casey points out in a column on Wall Street Journal website “Japan might be a hobbled economy but it is still the third largest in the world, accounting for almost one-tenth of world gross domestic product. So when the Bank of Japan prints as much yen as this, it provokes a worldwide adjustment in relative prices. Electronics producers in South Korea, Taiwan and, to an increasing degree, China, automatically face a price disadvantage versus their Japanese competitors, for example.”

Also interest rates on American and Japanese bonds are currently at very low levels. And this has sent investors looking for return to other parts of the world. Take the case of New Zealand. Foreign money has been flooding into the country. When foreign money comes into a country it needs to be exchanged for the local currency (the New Zealand dollar in case of New Zealand). This leads to a situation where the demand for the local currency increases, leading to its appreciation.

One New Zealand dollar was worth around 64.6 yen on October 1, 2012. It is currently worth around 84.4 yen. An appreciation in the value of a country’s currency hurts its exports. On Wednesday (May 8, 2013), the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, decided that it will intervene in the foreign exchange market to weaken the New Zealand dollar.

How does any central bank weaken its currency? When a huge amount of foreign money comes in, it increases the demand for local currency. The central bank at that point floods the foreign exchange market with its own currency, to ensure that there is enough of it going around. This ensures that the local currency does not appreciate. If the central bank floods the market with more local currency than the demand is, it ensures that the local currency loses value against the foreign money that is coming in.

The question is where does the central bank get this money from? It simply prints it.

The thing to remember is that if Japan can print money to cheapen its currency so can other countries like New Zealand. It is not rocket science. Its what Americans call a no brainer. In fact, yen started appreciating against the dollar once the Federal Reserve of United States, the American central bank, started printing money to revive economic growth. And this has also been responsible for Japan starting to print money. As Casey points out “Together, the U.S. Federal Reserve and the Bank of Japan will print the equivalent of $155 billion every month for an indefinite period.” This will spill over to more countries printing money to hold the value of their currency or even cheapen it.

The currency war which is currently on between countries as they print money to cheapen their currencies will only get worse in the days and months and years to come. Australia is expected to join this war very soon. Countries are also trying to control the flood of foreign money by cutting interest rates. The Australian central bank cut interest rates on Tuesday (i.e. May 7, 2013). The Bank of Korea, the South Korean central bank also cut interest rates on Thursday (i.e. May 9,2013). China has put measures in place to curb foreign inflows.

As Greg Canvan writes in The Daily Reckoning Australia “So as the US dollar moves above 100 yen for the first time in four years…Get ready for an escalation in the currency wars.”

To conclude, it is important to remember what H L Mencken, an American writer, once said “For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.” If only creating economic growth was just about printing more money…

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on May 11, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

A case for gold at $10,000 per ounce

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

The funny thing is that the more I think I will not write on gold, the more I end up writing on it. So here we go with one more piece analysing the prospects of the yellow metal.

The recent past has seen a host of analysts and economists turn negative on gold. One of the reasons for this has been the feeling that the developed world (US, Europe and Japan i.e.) which had been reeling under the aftermath of the financial crisis since 2008 is now on a roadmap to sustainable recovery.

The irony is that analysts and economists jump at any opportunity to predict a recovery but are nowhere to be seen when a recession is looming. As Albert Edwards of Societe Generale writes in a report titled We still forecast 450 S&P, sub-1% US 10year yields, and gold above $10,000 released yesterday “There are some ever-present truths in this business. Economists usually forecast a return to trend growth and will never forecast a recession. Equity strategists tend to forecast the market will rise 10% each year and will never forecast bear markets.”

So dear readers this is an important fact to be kept in mind when reading any dire forecast on gold. As Edwards puts it “The late Margaret Thatcher had a strong view about consensus. She called it: “The process of abandoning all beliefs, principles, values, and policies in search of something in which no one believes, but to which no one objects.” The same applies to most market forecasts. With some rare exceptions…analysts dont like to stand out from the crowd.”

And the consensus right now seems to be that gold is done with its upward journey. The logic being offered is that all the money printing that central banks around the world have indulged in since the end of 2008, has helped them repair their respective financial systems and economies. (To know why I don’t believe that is the case click here).

To achieve this economic stability a huge amount of money has been printed. As Gary Dorsch, an investment newsletter writer wrote in a recent column “So far, five central banks, – the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, Bank of England, the Bank of Japan and the Swiss National Bank have effectively created more than $6-trillion of new currency over the past four years, and have flooded the world money markets with excess liquidity. The size of their balance sheets has now reached a combined $9.5-trillion, compared with $3.5-trillion six years ago.”

While this money printing has ‘supposedly’ helped the countries in the developed world move towards economic stability, at the same time it has not led to any inflation, as it was expected to. And this is the main reason being cited by those who have turned bearish on gold.

Gold has always been bought as a hedge against the threat of high inflation. And if there is no inflation why buy gold is the argument being offered.

On the face of it this seems like a fair point to make. But lets try and understand why it doesn’t work. It is important to understand that free money does not and cannot exist. As Dylan Grice of Societe Generale wrote in a report titled The Market for honesty: is $10,000 gold fair value? released in September, 2011 “Since there can be no such thing as a government, or anyone else for that matter, raising revenue ‚at no cost‛ simple logic tells us that someone, somewhere has to pay.”

The point being that when the government finances itself by getting the central bank to print money, someone has to bear the cost.

The question is who is that someone. As Grice wrote “This is where the subtle dishonesty resides, because the answer is that no-one knows. If the money printing creates inflation in the product market, the consumers in that product market will pay. If the money printing creates inflation in asset markets, the purchaser of the more elevated asset price pays. Of course, if the printed money ends up in asset markets even less is known about who ultimately pays for the government’s ‘free lunch’…The ‘free lunch’ providers will be the late entrants into whatever asset-bubble or investment fad the money printing inflates.”

So how does this work in the current context? While the money printing hasn’t led to product inflation in the developed world, the stock markets in the developed world, particularly in the United States and Japan, have been rallying big time. Despite the fact that the respective economies are not in the best of shape. Hence, the money printing even though it hasn’t led to consumer price inflation, it has led to inflation in the stock market. And those investors who will enter these stock markets late, will ultimately bear the cost of all the money printing.

Money that leaves the printing presses of the government need not always end up with people, who use it to buy consumer products and thus push up their price. As Grice puts it “By now, some of you might feel this all to be irrelevant. Surely, you might be thinking, the plain fact is that there is no inflation. I disagree. To see why, think about what inflation is in the light of the above thinking. I know economists define it as changes in the price of a basket of consumer goods, the CPI(consumer price index). But why should that be the definitive measure, given that it’s only one of the many possible destinations in money’s Brownian journey from the printing presses? Why ignore other destinations, such as asset markets? Isn’t asset price inflation (or bubbles as they are more commonly known) more distortionary and economically inefficient than product price inflation?”

The consumer price index which measures inflation is looked at as a definitive measure by economists. But there are problems with the way it is constructed. As a recent report titled Gold Investor: Risk Management and Capital Preservation released by the World Gold Council points out “The weights that different goods and services have in the aforementioned indices do not always correspond to what a household may experience. For example, tuition has been one of the fastest growing expenses for US households but represents only 3% of CPI (consumer price index). In practice, tuition costs correspond to more than 10% of the annual income even for upper-middle American households – and a higher percentage of their consumption.”

This helps in understating the actual inflation number. There are other factors at play as well which work towards understating the actual inflation number. As the World Gold Council report points out “Consumer price baskets are frequently adjusted to incorporate the effect that advancement in technology (e.g. in computer hardware) have on prices paid. These so called hedonic adjustments can overstate reductions in price compared to what consumers pay in practice. For example, a new computer can have the same nominal price as it did five years ago, but adjusting for the processing speed and storage capacity it appears cheaper.”

Then there are also methodological changes that have been made to the consumer price index and the way it measures inflation over the years, which in practice do not always reflect the full erosion of the purchasing power of money.

The following chart shows that if inflation in the United States was still measured as it was in the 1980s would be now close to 10% instead of the official 2%.

The moral of the story is that the situation is not as simple as those who have turned bearish on gold are making it out to be. Given that, how does one view the recent fall in prices of gold on the back of this evidence? As Edwards puts it “Gold corrected 47% from 1974-1976 before rising more than 8x to US$887/oz in 1980. A steep correction is normal before the parabolic move.”

Both Edwards and Grice expect gold to touch $10,000 per ounce (one troy ounce equals 31.1 grams). As I write this gold is currently quoting at $1460 per ounce, having risen from the low of $1350 per ounce that it touched sometime back.

Central banks around the world have tried to create economic growth by printing money. But their efforts to do so are likely to backfire. As Edwards writes “My working experience of the last 30 years has convinced me that policymakers’ efforts to manage the economic cycle have actually made things far more volatile. Their repeated interventions have, much to their surprise, blown up in their faces a few years later. The current round of QE will be no different. We have written previously, quoting Marc Faber, that “The Fed Will Destroy the World” through their money printing. Rapid inflation surely beckons.”

And that’s the point to remember: rapid inflation surely beckons. And to be prepared for that it is important to have investments in gold, the recent negativity around it notwithstanding.

To conclude let me again emphasise that this is how I feel about gold. I may be right. I may be wrong. That only time will tell. So please don’t bet your life on it and limit your exposure to gold to around 10% of your overall investment.

It is important to remember the first few lines of Ruchir Sharma’s Breakout Nations: “The old rule of forecasting was to make as many forecasts as possible and publicise the ones you got right. The new rule is to forecast so far into the future that no one will know you got it wrong.”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on April 26, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek. He has investments in gold through the mutual fund route)

What the humble electric toaster tells us about the global financial system

Vivek Kaul

Tim Harford writer of such excellent books like The Undercover Economist, The Logic of Life and Adapt, once wrote a blog discussing the perils of a design student trying to make an electric toaster from scratch.

Harford discusses the experience of Thomsan Thwaites, a postgraduate design student, who decided to embark on what he called “The Toaster Project”. “Quite simply, Thwaites wanted to build a toaster from scratch,” writes Harford.

The toaster was first invented in 1893 and is a household good in Great Britain and almost all other parts of the developed world. It costs a few pounds and is very reliable and efficient. But building it from scratch was still not a joke. “To obtain the iron ore, Thwaites had to travel to a former mine in Wales that now serves as a museum. His first attempt to smelt the iron using 15th-century technology failed dismally. His second attempt was something of a cheat, using a recently patented smelting method and a microwave oven – the microwave oven was a casualty of the process – to produce a coin-size lump of iron,” writes Harford.

Next Thwaites needed plastic. Plastic is made from oil. But Thwaites never made it to an oil rig. He finally settled at scavenging plastic from a local dump, which he melted and then moulded into a toaster casing.

More short cuts followed. As Harford writes “Copper he obtained via electrolysis from the polluted water of an old mine… Nickel was even harder; he cheated and bought some commemorative coins, melting them with an oxyacetylene torch. These compromises were inevitable.”

A simple toaster has nearly 400 components and sub components which is made from nearly 100 different materials. So imagine the difficulty if everything had to be procured and made from scratch. As Thwaites told Harford “I realised that if you started absolutely from scratch, you could easily spend your life making a toaster.”

Thwaites finally did manage to make an electric toaster, but it was nowhere as good as the ones easily available in the market. As Harford writes “Thwaites’s home-made toaster is a simpler affair, using just iron, copper, plastic, nickel and mica, a ceramic. It looks more like a toaster-shaped birthday cake than a real toaster, its coating dripping and oozing like icing gone wrong. “It warms bread when I plug it into a battery,” he says, brightly. “But I’m not sure what will happen if I plug it into the mains.””

So dear reader, you might be reading this piece sitting in the air-conditioned comforts of your office on an ergonomically designed chair (hopefully). Or you might be sitting at home reading this on your laptop. Or you must be travelling in a bus/metro/local train hanging onto your life and reading this on your android smartphone. Or you must be waiting for your aircraft to take off and must be quickly glancing through this on your iPad.

The question that crops up here is that how many of the things mentioned in the last paragraph, would you dear reader, be able to make on your own? The answer is none. So then where did all these things that make life so comfortable come from?

Dylan Grice answers this question in the latest issue (dated March 11, 2013) of the Edelweiss Journal. “So where did it all come from? Strangers, basically. You don’t know them and they don’t know you. In fact virtually none of us know each other. Nevertheless, strangers somehow pooled their skills, their experience and their expertise so as to conceive, design, manufacture and distribute whatever you are looking at right now so that it could be right there right now.”

Estimates suggest that cities like London and New York offer ten billion distinct kinds of products. So what makes this possible? “Exchange. To be able to consume the skills of these strangers, you must sell yours,” writes Grice. It is impossible for a single human being to even make something as simple as a toaster from scratch. But when many people specialise in their respective areas and develop certain skills, only then does a product as simple as a toaster become possible.

Let me take my example. I sell my writing skills. With the compensation that I get I buy goods and services that I need for my existence. From something as basic as food, water and electricity, which I need to survive or comforts like buying a washing machine to wash clothes, a refrigerator so that I don’t need to cook on a day to day basis, hiring a taxi to travel in or catching the latest movie at the local multiplex.

At the heart of any exchange is trust. As Grice puts it “we must also understand that exchange is only possible to the extent that people trust each other: when eating in a restaurant we trust the chef not to put things in our food; when hiring a builder we trust him to build a wall which won’t fall down; when we book a flight we entrust our lives and the lives of our families to complete strangers.”

So for any exchange to happen, there needs to be trust. But trust is not the only thing that facilitates exchange. There is another important ingredient. And that is money.

Money has been thoroughly abused all over the world in the aftermath of the financial crisis which broke out officially in September 2008. Central banks egged on by governments all over the world have printed money, in an effort to revive their respective economies. The idea being that with more money in the financial system, banks will lend more which will lead to people spending more and that will help revive the economy.

But all this comes with a cost. “So when central banks play the games with money of which they are so fond, we wonder if they realize that they are also playing games with social bonding. Do they realize that by devaluing money they are devaluing society?” asks Grice.

Allow me to explain. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, government expenditure all over the world has shot up dramatically. This expenditure could have been met by raising taxes. But when economies are slowing down this isn’t the most prudent thing to do. The next option was to borrow money. But there was only so much money that could be borrowed. So the governments utilised the third possible option. They got their central banks to print money. Central banks used this printed money to buy government bonds. Thus the governments could meet their increased expenditure.

When a government increases tax to meet its expenditure, everyone knows who is paying for it. It’s the taxpayer. But the answer is not so simple when the government meets its expenditure by printing money. As Grice puts it “When the government raises revenue by selling bonds to the central bank, which has financed its purchases with printed money, no one knows who ultimately pays.”

But then that doesn’t mean that nobody pays.

With the central bank printing money, the money supply in the financial system goes up. And this benefits those who are closest to the “new” money. Richard Cantillon, a contemporary of Adam Smith, explained this in the context of gold and silver coming into Spain from what was then called the New World (now South America).

As he wrote: “If the increase of actual money comes from mines of gold or silver… the owner of these mines, the adventurers, the smelters, refiners, and all the other workers will increase their expenditures in proportion to their gains.” These individuals would end up with a greater amount of gold and silver, which was used as money, back then. This money they would spend and thus drive up the prices of meat, wine, wool, wheat etc. This rise in prices would impact even people not associated with the mining industry even though they wouldn’t have seen a rise in their incomes like the people associated with the mining industry had.

So is this applicable in the present day context? The money printing that has happened in recent years has benefited those who are closest to the money creation. This basically means the financial sector and anyone who has access to cheap credit. Institutional investors have been able to raise money at close to zero percent interest rates and invest them in all kinds of assets all over the world. As Ruchir Sharma writes in Breakout Nations – In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles:

“What is apparent that central banks can print all the money they want, they can’t dictate where it goes. This time around, much of that money has flown into speculative oil futures, luxury real estate in major financial capitals, and other non productive investments…The hype has created a new industry that turns commodities into financial products that can be traded like stocks. Oil, wheat, and platinum used to be sold primarily as raw materials, and now they are sold largely as speculative investments.”

While financial investors benefit, the common man ends up paying more for the goods and services that he buys, something that is not always captured in the inflation number. As Grice puts it: “So now we know we have a slightly better understanding of who pays: whoever is furthest away from the newly created money. And we have a better understanding of how they pay: through a reduction in their own spending power. The problem is that while they will be acutely aware of the reduction in their own spending power, they will be less aware of why their spending power has declined. So if they find groceries becoming more expensive they blame the retailers for raising prices; if they find petrol unaffordable, they blame the oil companies; if they find rents too expensive they blame landlords, and so on. So now we see the mechanism by which debasing money debases trust. The unaware victims of this accidental redistribution don’t know who the enemy is, so they create an enemy.”

And people all over the world are doing a thoroughly good job of creating “enemies”. “The 99% blame the 1%; the 1% blame the 47%. In the aftermath of the Eurozone’s own credit bubbles, the Germans blame the Greeks. The Greeks round on the foreigners. The Catalans blame the Castilians. And as 25% of the Italian electorate vote for a professional comedian whose party slogan “vaffa” means roughly “f**k off ” (to everything it seems, including the common currency), the Germans are repatriating their gold from New York and Paris. Meanwhile in China, that centrally planned mother of all credit inflations, popular anger is being directed at Japan.”

This is only going to increase in the days and years to come. As Grice writes in a report titled Memo to Central Banks: You’re debasing more than our currency (October 12, 2012) “History is replete with Great Disorders in which social cohesion has been undermined by currency debasements…Yet central banks continue down the same route. The writing is on the wall. Further debasement of money will cause further debasement of society. I fear a Great Disorder.”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on March 21, 2013

Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek