A favourite pastime of former finance minister P Chidambaram other than telling us that the Indian economic growth was about to bounce back, was to ask the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to cut interest rates.

The new finance minister Arun Jaitley has carried on from where Chidambaram left. On August 10, Jaitley had nudged the RBI to cut interest rates after taking various factors into account.

The thing with most politicians is that either they do not understand how a market operates or they pretend otherwise. Jaitley and Chidambaram, I assume would fall into the latter category. Allow me to explain.

The latest RBI annual report points out that “the household financial saving rate remained low during 2013-14, increasing only marginally to 7.2 per cent of GDP in 2013-14 from 7.1 per cent of GDP in 2012-13 and 7.0 per cent of GDP in 2011-12…the household financial saving rate [has] dipped sharply from 12 per cent in 2009-10.”

Household financial savings is essentially the money invested by individuals in fixed deposits, small savings scheme, mutual funds, shares, insurance etc. The household financial savings were at 12% of the GDP in 2009-10. Since then, they have fallen dramatically to 7.2% in 2013-14. A major reason for the fall has been the high inflation that has prevailed since 2008.

This has had two impacts. One is that expenses of people have consistently gone up, leading to lower savings. Further, of the money that was saved a higher proportion was directed towards physical savings like gold and real estate. This was done because the rate of return available on financial savings was much lower than the rate of return on gold as well as real estate. The average savings in physical assets between 2005-06 and 2007-08 stood at 11.4% of the GDP. This shot up to 14.8% in 2012-13(the data for 2013-14 is not available).

What has not helped is the fact that over the last few years the fiscal deficit of the government shot up dramatically, as its expenditure shot up at a much faster rate, in comparison its income. Fiscal deficit of the government is the difference between what it earns and what it spends. This increase in fiscal deficit was financed through increased borrowing.

In fact, buried in the second chapter of the Economic Survey of 2013-2014 is a very interesting data point. In 2012-2013, the household financial savings amounted to 7.1% of the GDP. The government borrowing stood at 7% of the GDP. A similar comparison for 2013-2014 is not available yet. Nevertheless, it would be safe to assume that it won’t be materially different from the 2012-2013 comparison.

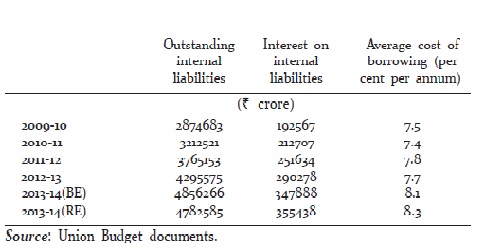

The conclusion that one can draw from this is that entire household financial savings were used up to fund the fiscal deficit. This is also reflected in the following table from the Economic Survey.

As the government borrowed more and more, eating up into the household financial savings, the cost of its borrowing also went up. In 2009-10, the average cost of borrowing stood at 7.5%. By 2013-2014, this number had shot up to 8.3%.

Lending to the government is the safest form of lending. Hence, the rate of interest that the government pays on its borrowing becomes the benchmark for all other kind of loans. Also, with greater borrowing, it left a lower amount of money available for others outside the government to borrow. As the Economic Survey pointed out “In recent years, with a decline in the savings rate and an enlarged fiscal deficit, the external capital from outside the firm, available to the private sector has declined.”

So, with the government paying a higher rate of interest on its debt, and not enough money going around for others (which included banks) to borrow, it isn’t surprising that you and I had higher EMIs to pay.

To cut a long story short, if interest rates need to come down, the government needs to borrow less. If the government has to borrow less, it needs to spend less or try and increase its income. If this happens, there will be more money going around for everyone else to borrow, and will lead to a fall in interest rates.

Unless these things happen, any call by the finance minister asking the RBI to cut interest rates needs to be taken with a pinch of salt. The RBI may decide to humour the finance minister and go ahead and cut the repo rate (the rate at which it lends to banks). Nevertheless, any material fall in interest rates will happen only once the government is able to make serious efforts towards curtailing the fiscal deficit.

And the next time you hear Jaitley asking the RBI to cut interest rates, remember, he is trying to do a Chidambaram on us.

The article originally appeared on www.Firstbiz.com on August 23, 2014