Vivek Kaul

Nothing works like the formula. And the formula to rescue a bank which is in trouble is to merge it with another bank. Reports in the media seem to suggest that there might be plans to merge the troubled United Bank of India with the Union Bank of India.

In fact, on February 24, 2014, the share price of United Bank jumped by 13.75% on this possibility, in the early morning trade. It finally closed the day 6% higher at Rs 25.8 , from its closing price on February 21, 2014.

As has been reported before, the United Bank of India is in major trouble. For the period of three months ending December 2013, the bank reported a loss of Rs 1,238 crore. This, after it had provided Rs 1,858 crore against bad loans.

During the period, the bank’s gross non performing assets (NPA) increased by a whopping 36% to Rs 8,545.5 crore. This amounted to nearly 10.8% of the total loans given out by the bank. In fact, in December the Reserve Bank of India(RBI) had asked United Bank not to give a loan of greater than Rs 10 crore to any single borrower. A recent report in the Mint newspaper points out that the bank has issued an internal directive not to make any fresh loans, unless they are backed by the mortgage of fixed deposits.

In this scenario it is not surprising that there is speculation of the bank being merged with the Union Bank of India. Having said that, the United Bank has denied any such possibilities.

But given the past record of the government merging a bank in trouble with another bank, the merger of the United Bank with the Union Bank(or any other public sector bank) is a possibility that remains. The troubled Global Trust Bank was merged with the state run Oriental Bank of Commerce in 2004. In 2002, the Benares State Bank was merged with the Bank of Baroda. Before this, in 1988, the Hindustan Commercial Bank was merged with the Punjab National Bank. The Punjab National Bank also came to the rescue of Nedungadi Bank in 2003.

So there is a clear trend of a failing bank being merged with an existing bank. In the examples given above, all the failing banks were private sector banks and they were taken over by public sector banks. The United Bank of India is a public sector bank in which the government has a stake of 88%.

This makes it even more likely that the government will try and do everything to save the bank. The total assets of the United Bank as on March 31, 2013, amounted to Rs 1,14,615 crore. The Union Bank is around 2.7 times bigger and has total assets of Rs 3,12,912 crore.

If the banks had been merged on March 31, 2013, the total assets of the new bank would amount to around Rs 4,27,527 crore. The assets of the United Bank would form around 26.8% of the merged entity. Given this, the erstwhile United Bank would form a significant part of the merged entity.

Hence, with nearly 10.8% of its total loans being classified as gross non performing assets, it is possible that the bad loans of United Bank may dramatically pull down the performance of the merged entity.

Let’s take the case of Oriental Bank of Commerce. In August 2004, the Global Trust Bank, which had run into trouble due to bad lending, was merged with the Oriental Bank of Commerce. For the year ending March 31, 2004, the Oriental Bank of Commerce had reported a profit of Rs 686 crore.

The merger destablized Oriental Bank of Commerce and the net profit fell to Rs 557 crore for the year ending March 31, 2006 and took a few years to recover.

A similar thing will happen with the Union Bank of India, if the United Bank is merged into it. Also, it is worth pointing out that most public sector banks are already in trouble, given the mounting amount of bad loans on their books. As the latest RBI Financial Stability Report points out “Among the bank-groups, the public sector banks continue to have distinctly higher stressed advances at 12.3 per cent of total advances, of which restructured standard advances were around 7.4 per cent.”

So, merging United Bank with Union Bank or any other public sector bank for that matter means destablizing the Union Bank as well and in the process creating more trouble for the entire banking sector.

It will also bring to the fore the issue of “moral hazard”. Before we get into discussing this, it is important to understand what moral hazard means. As Alan S Blinder writes in After the Music Stopped “The central idea behind moral hazard is that people who are well insured against some risk are less likely to take pains ( and incur costs) to avoid it. Here are some common non financial examples: …people who are well insured against fire may not install expensive sprinkler systems; people driving cars with more safety devices may drive less carefully.”

Given this, insurance companies must take into account the fact that insurance may induce people to take on more risk. “In financial applications, moral hazard concerns arise whenever some third party—often the government—intervenes to insure against or lessen the consequences of, the risk of loss,” writes Blinder.

In fact, the American economy is a great example of all that can go wrong because of moral hazard. Since the 1980s, scores of financial institutions in trouble have been rescued by the government. The signal this sends out to the participants in the financial system is that they can take on more and more risk, and if something does not work out well, the government will come to their rescue.

This is precisely what happened in the United States, where banks took on more and more risk, confident of the fact that if something went wrong, the American government would come to the rescue.

If the United Bank is merged with the Union Bank (or any other public sector bank), this is the signal that will be sent out. Hence, it is important the United Bank not be rescued by the government.

This does not mean that the bank should be allowed to fail. The government needs to protect the depositors of the bank. As has been suggested before here the government should look to sell the bank to any private businessman for Re 1, who can then run it. Also, India currently has 21 public sector banks, and one less public sector bank will really not make much of a difference to the overall financial system.

The article originally appeared on www.FirstBiz.com on February 25, 2014

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

FirstBiz

Google Plus versus Facebook: How a big brand can win even without the best product

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

Google+ was launched sometime in 2011. It got rave reviews and many technology enthusiasts claimed that it was much better than Facebook and advised users to switch. More than two years later Facebook continues to be the leader and Google+ is at best an also ran.

The moral of the story is that a better product doesn’t always win in the market place. And there are various reasons for the same. In case of Google Plus versus Facebook it was a clear case of the network effect.

As Niraj Dawar writes in Tilt – Shifting Your Strategy from Products to Customers “For those who want to be a part of a social network, it makes sense to congregate where everybody else is hanging out. There is only one village square on the Internet, and it is run by Facebook. Being on a different square from everyone else doesn’t get you anywhere—you just miss the party.”

This was the main reason why people did not move from Facebook to Google+, even though it may have been the better product. “Google + may offer features such as greater privacy or group video chat,” writes Dawar, but it fails to “create the positive feedback loop, because it makes sense for everybody to be where everybody else already is.”

Hence, people stayed on Facebook because everyone else was on it as well. So, even though most people may have the mandatory Google+ account, but ask them where they spend a good amount of their social networking time, and the answer you will get is Facebook.

An excellent example of the network effect being the main reason for the success of a product is the WhatsApp messenger. Despite the fact that there are other players in the market which are advertising very heavily, WhatsApp continues to hold its ground.

Another area where the network effect plays out these days are the movies. “With social networks’ rapid dissemination of information, these types of brand network effects have been turbocharged—they occur more rapidly and forcefully than ever before. A movie now flops or hits as a result of the first forty-eight hours of tweeting and box office sales,” writes Dawar. The holiday season and long weekends are littered with examples of several bad movies, which people watched because everyone else had.

At times what also happens is that the criteria for success that the company had backed on, turns out to be different from what consumers think it should be. Take the case of the VHS versus Betamax battle for the video standard, between Sony and Matsushita, both Japanese companies. Sony decided to concentrate on video quality whereas Matsushita decided to concentrate on longer recording time, which ultimately became the key differentiator between the two standards.

By concentrating on the quality of the video Sony was just doing what it had done in the past. But consumers, it turned out, were looking for a longer recording time and were willing to compromise on the quality of the video.

At times, the consumers don’t have a role to play and have to go with what is offered. Take the case of the battle between Blu-ray and HD-DVD, two competing DVD formats. As Karl Stark and Bill Stewart write in an article titled Why Better Products Don’t Always Winon Inc.com “Unfortunately differentiating factors aren’t always clear, and consumers don’t always get the right to choose. Consider the battle between Blu-ray and HD-DVD; while consumers could buy either product, ultimately the war was fought over which content providers would exclusively back each format. Since more content was available on Blu-ray, it ended up creating more customer value, despite the possibility that HD-DVD was a technically superior product.”

Once the consumer is on the Blu-ray format, there is a huge cost of switching to HD-DVD, even though HD-DVD may catch up in terms of content that is available on it to be viewed.

On occasions what also happens is that the brand association of a particular product being the best product in that category is very strong and competitors can’t break it. Take the case of Gillette. As Dawar writes “After more than a century of blade technology, Gillette still controls when the market moves onto the next generation of razor and blade. And even though for the past three decades, competitors have known that the next-generation blade from Gillette will carry one additional cutting edge and some added swivel or vibration, they’ve never pre-empted the third, fourth, or fifth blade.”

Why is that the case? “Because there is little to gain from preemption. Gillette owns the customers’ criterion, and the additional blade becomes credible and viable only when Gillette decides to introduce it, backed by a billion-dollar launch campaigns.”

The chip maker Intel is in a similar sort of situation. Consumers believe that the chip is the fastest chip in the market, only if it comes from Intel. “Both AMD’s K-6 chip and the PowerPC chip were faster than the fastest Intel chip on the market at the time of their launch. But the two challengers were unable to move the market,” writes Dawar.

To conclude, let me quote Stark and Stewart: “Better products win when the total value – that is, the benefits minus the cost – is clear and measurable to the customer and creates more value than comparable offerings.” The trouble is it is difficult to figure out in advance what creates more value for the customer. Even the customer may not know the answer to that question.

The article originally appeared on www.FirstBiz.com on February 25, 2014

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Crony capitalism: The truth about Indian banking is finally coming out

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

One of the well kept secrets about the fragile state of the Indian economy is gradually coming out in the open. The Indian banks are not in great shape. The Financial Express reports that the chances of a lot of restructured loans never being repaid has gone up. It quotes R K Bansal, chairman of the corporate debt restructuring (CDR) cell, as saying that the rate of slippages could go up to 15% from the current levels of 10%. “The slower-than-expected economic recovery and delayed clearances for projects will result in a higher share of failed restructuring cases,” Bansal told the newspaper.

When a big borrower (usually a company) fails to repay a bank loan, the loan is not immediately declared to be a bad loan. The CDR cell is a facility available for banks to try and rescue the loan. Loans are usually restructured by extending the repayment period of the loan. This is done under the assumption that even though the borrower may not be in a position to repay the loan currently due to cash flow issues, chances are that in the future he may be in a better position to repay the loan. Or as John Maynard Keynes once famously said “If you owe your banka hundred pounds, you have a problem. But if you owe a million, it has.”

As of December 2013, the CDR cell had restructured loans of around Rs 2.9 lakh crore. Of this nearly 10% of the loans have turned into bad loans with promoters not paying up. Bansal expects this number to go up to 15%. Interestingly, a Reserve Bank of India (RBI) working group estimates that nearly 25-30% of the restructured loans may ultimately turn out to be bad loans.

And that is clearly a worrying sign. There is more data that backs this up. In the financial stability report released in December 2013, the RBI estimated that the average stressed asset ratio of the Indian banking system stood at 10.2% of the total assets of Indian banks as of September 2013. It stood at 9.2% of total assets at the end of March 2013.

The average stressed asset ratio is essentially the sum of gross non performing assets plus restructured loans divided by the total assets held by the Indian banking system. What this means in simple English is that for every Rs 100 given by Indian banks as a loan(a loan is an asset for a bank) nearly Rs 10.2 is in shaky territory. The borrower has either stopped to repay this loan or the loan has been restructured, where the borrower has been allowed easier terms to repay the loan (which also entails some loss for the bank).

The RBI financial stability report points out that this has happened because of bad credit appraisal by the banks during the boom period. “It is possible that boom period[2005-2008] credit disbursal was associated with less stringent credit appraisal, amongst various other factors that affected credit quality,” the report points out. Hence, borrowers who shouldn’t have got loans in the first place, also got loans, simply because the economy was booming, and bankers giving out loans felt that their loans would be repaid. But that hasn’t turned out to be the case.

Interestingly, Uday Kotak, Managing Director of Kotak Mahindra Bank recently told CNBC TV 18 that the current stressed, restructured or non performing loans amounted to nearly 25% of the Indian banking assets. He put the total number at Rs 10 lakh crore of the total loans of Rs 40 lakh crore given by the Indian banking system. This is a huge number.

Kotak further said that the Indian banking system may have to write off loans worth Rs 3.5-4 lakh crore over the next few years. When one takes into account the fact that the total networth of the Indian banking system is around Rs 8 lakh crore, one realizes that the situation is really precarious.

Interestingly, a few business sectors amount for a major portion of these troubled loans. As the RBI report on financial stability points out “There are five sectors, namely, Infrastructure, Iron & Steel, Textiles, Aviation and Mining which have high level of stressed advances. At system level, these five sectors together contribute around 24 percent of total advances of SCBs (scheduled commercial banks), and account for around 51 per cent of their total stressed advances.”

So, five sectors amount to nearly half of the troubled loans. If one looks at these sectors carefully, it doesn’t take much time to realize these are all sectors in which crony capitalism is rampant (the only exception probably being textiles).

Take the case of L Rajagopal of the Congress party (who recently used the pepper spray in the Parliament). He is the chairman and the founder of the Lanco group, which is into infrastructure and power sectors. As Shekhar Gupta pointed out in a recent article in The Indian Express, Rajagopal’s “company got a Rs 9,000 crore reprieve in a CDR (corporate debt restructuring) process just the other day. His bankrupt companies were given further loans of Rs 3,500 crore against an equity of just Rs 239 crore. Twenty-seven banks were involved in that bailout.”

Here is a company which hasn’t repaid loans of Rs 9,000 crore. It benefits from the restructuring of those loans and is then given further loans worth Rs 3,500 crore. So, if the Indian banking sector is in a mess, it is not surprising at all.

As bad loans mount, banks will go slow on giving out newer loans. They are also likely to charge higher rates of interest from those borrowers who are repaying the loans. This is not an ideal scenario for an economy which needs to grow at a very fast rate in order to pull out more and more of its people from poverty. If India has to go back to 8-9% rate of economic growth, its banks need to be in a situation where they should be able to continue to lend against good collateral.

So is there a way out of this mess? A suggestion on this front has come from Saurabh Mukherjea from Ambit. He suggests that the bad assets be taken off from the balance sheets of banks and these assets be moved to create a “bad bank”. This would allow the good banks to operate properly, without worrying about the bad loans on its books. As he writes “This would, in effect, nationalise the bad assets of the Indian banks and the taxpayer would have to bear the burden of these sub-standard loans.”

The government had followed this strategy to rescue Unit Trust of India (UTI). All the bad assets were moved to SUUTI (Specified Undertaking of the Unit Trust of India). The good assets were moved to the UTI Mutual Fund, which has flourished over the years. The government also has gained in the process.

The trouble here is that even if the government does this, there is no guarantee that it might be successful in reining in the crony capitalists. Over the last 10 years crony capitalists like Rajagopal, who are close to the Congress party, have benefited out of the Indian banking system. Given this, it is but natural to assume that after May 2014, the crony capitalists close to the next government (which in all likeliness will be led by Narendra Modi) will takeover. And that is the real problem of the Indian banking sector, for which there can be no solution other than a political will to clean up the system.

The article originally appeared on www.firstbiz.com on February 25, 2014

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

How Chidambaram, UPA have turned India into a ponzi scheme

The Congress led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government has turned India into a big Ponzi scheme. Allow me to explain.

Most governments all over the world spend more than they earn. This difference is referred to as the fiscal deficit and is financed through borrowing. Any government borrows by selling bonds. On these bonds a certain rate of interest is paid every year by the government to the investor who has bought these bonds.

The bonds also have a certain maturity period and once they mature the money invested in the bonds needs to be repaid by the government to the investor who had bought these bonds.

The trouble is that India has reached a stage where the sum of the interest that the government needs to pay on the existing bonds along with the money the government requires to repay the maturing bonds is greater than the value of fresh bonds being issued (which is equal to the value of the fiscal deficit).

Take the current financial year 2013-2014 (i.e. the period between April 2013 and March 2014). The interest to be paid on existing bonds amounts to Rs 3,80,067 crore. The amount that needs to be paid to investors who hold bonds that are maturing is Rs 1,63,200 crore. This total, referred to as the debt servicing cost, comes to Rs 5,43,267 crore (as can be seen in the following table).

The ratio of the debt servicing cost divided by fiscal deficit(referred to as the Ponzi ratio in the above table) for the year 2013-2014 comes to 1.04 (Rs 5,43,267 crore/ Rs 5,24,539 crore). What this means in simple English is that the government is issuing fresh bonds and raising money to repay maturing bonds as well as to pay interest on the existing bonds.

The ratio of the debt servicing cost divided by fiscal deficit(referred to as the Ponzi ratio in the above table) for the year 2013-2014 comes to 1.04 (Rs 5,43,267 crore/ Rs 5,24,539 crore). What this means in simple English is that the government is issuing fresh bonds and raising money to repay maturing bonds as well as to pay interest on the existing bonds.

This is akin to a Ponzi scheme, in which money brought in by new investors is used to redeem the payment that is due to existing investors. So investors buying new bonds issued by the government are providing it with money, to repay the older investors, whose interest is due and whose bonds are maturing. The Ponzi scheme runs till the money being brought in by the new investors is greater than the money being paid out by the existing investors.

In the Indian case, the Ponziness has gone up over the years. In 2009-2010, the Ponzi ratio was at 0.70. This means that money raised by 70% of the new bonds issued by the government went towards meeting the debt servicing cost. In 2013-2014, the Ponzi ratio touched 1.04. This means that the money raised through all the fresh bonds issued were used to pay for the interest on existing bonds and repay the maturing bonds.

In fact, the projection for 2014-2015 (i.e. the period between April 2014 and March 31, 2015) puts the Ponzi ratio at 1.28. This means that all the money collected through issuing fresh bonds will go towards debt servicing. But over and above that a certain portion of the government earnings will also go towards meeting the debt servicing cost.

The increasing level of the Ponzi ratio from 0.70 in 2009-2010 to 1.28 in 2014-2015, is a clear indication of the fiscal profligacy that the Congress led UPA government has indulged in over the last few years. This has led to a situation where the expenditure of the government has shot up much faster than its earnings. This difference has been financed by the government issuing more bonds. Now its gradually reached a stage wherein the government needs to issue more and more new bonds to pay interest on the existing bonds and repay the maturing bonds.

This is nothing but a giant Ponzi scheme. To unravel, this Ponzi scheme the next government will have to cut down on expenditure dramatically. At the same time it will have to look at various ways of increasing its earnings.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on February 18, 2014

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

How Chidambaram has screwed the next govt even before it takes over

Vivek Kaul

What we don’t achieve ourselves, we expect from others.

This is a statement I have oft used during family conversations in the context of the “unrealistic” expectations parents and grandparents have from their children and grandchildren.

But it is also true for the current Congress party led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government. After spending much more than it earned for close to six years now, and managing to screw up the Indian economy left, right and centre, the Congress-led UPA government wants the government that takes over after the next Lok Sabha elections scheduled later this year, to cut down on the fiscal deficit.

The fiscal deficit target set for the financial year 2014-15 (i.e. the period between April 2014 and March 2015) is at 4.1 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP). Fiscal deficit is essentially the difference between what a government earns and what it spends expressed as a percentage of GDP.

The Congress led UPA government set a fiscal deficit target of Rs 1,33,287 crore or 2.5% of the GDP in the financial year 2008-09 (i.e. the period between April 2008 and March 2009). The actual number came in at Rs 3,36,992 crore or 6 percent of the GDP. And so started an era of fiscal profligacy.

The fiscal deficit target set for the financial year 2013-2014 (i.e. the period between April 2013 and March 2014) was set at Rs 5,42,499 crore or 4.8% of the GDP. But it is expected to come in at Rs 5,24,539 crore or 4.6% of the GDP.

This is primarily a result of accounting shenanigans as explained earlier and does not reflect the true state of the government accounts.

The fiscal deficit target set by the finance minister P Chidambaram for the next financial year is at Rs 5,28,631 crore or 4.1% of the GDP. Prima facie, the target is unachievable and there are several reasons for the same.

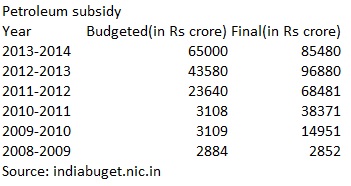

The petroleum subsidy allocated for 2014-15 stands at Rs 63,426.95 crore. In comparison, the petroleum subsidy for 2013-14 has come in at Rs 85,480 crore. This after, Rs 65,000 crore had been allocated towards it, at the beginning of the year.

Even a higher allocation of Rs 85,480 crore is not enough, given that the under-recoveries of the oil marketing companies for the first nine months of the year stand at Rs 1,00,632 crore during the first nine months of 2013-14 (April-December) on the sale of diesel, PDS Kerosene and cooking gas. The interesting bit here is that since 2009-10, the government has never been able to match the petroleum subsidy it allocated originally at the beginning of the year (as can be seen from the following table).

Take the case of 2012-13, when Rs 43,580 crore was allocated towards petroleum subsidy at the beginning of the year. The actual bill came in at close to Rs 96,880 crore, which was more than double. Given this, it is highly unlikely that Rs 63,426.95 crore will turn out to be enough.

This means greater expenditure for the government, and hence, a higher fiscal deficit, unless of course it balances the expenditure by cutting down asset creating planned expenditure. That is not the best strategy to follow, especially in a scenario of low economic growth which currently prevails.

Interestingly, even after making a higher allocation, a portion of subsidy payments is typically postponed to the next year. Estimates suggest that this year close to Rs 1,23,000 crore of subsidies have been postponed to the next year. The next finance minister would have to meet this expenditure.

If this expenditure has to be made and assuming that everything else stays equal, the fiscal deficit of the government would shoot to Rs 6,51,631 crore (Rs 5,28,631 crore + Rs 1,23,000 crore) or 5.1% of the GDP, against the currently assumed 4.1% of the GDP.

The only way the next finance minister would be able to meet the fiscal deficit target of 4.1% of the GDP, would be by following Chidambaram’s strategy of postponing expenditure, which is not the best way to go about it.

Another interesting point is the allocation of Rs 1,15,000 crore made towards food subsidies. Prima facie this does not seem to be enough to meet the commitments of the Food Security Act.

The government estimates suggest that food security will cost Rs 1,24,723 crore per year. But that is just one estimate. Andy Mukherjee, a columnist with Reuters, puts the cost at around $25 billion. The Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices(CACP) of the Ministry of Agriculture in a research paper titled National Food Security Bill – Challenges and Options puts the cost of the food security scheme over a three year period at Rs 6,82,163 crore. During the first year (which 2014-15 more or less is) the cost to the government has been estimated at Rs 2,41,263 crore.

Economist Surjit Bhalla in a column in The Indian Express put the cost of the scheme at Rs 3,14,000 crore or around 3 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP). Ashok Kotwal, Milind Murugkar and Bharat Ramaswami challenge Bhalla’s calculation in a column in The Financial Express and write “the food subsidy bill should…come to around 1.35% of GDP.”

Even at 1.35 percent of the GDP, the cost of the food security scheme comes in at close to Rs 1,73,000 crore (1.35 percent of Rs 12,839,952 crore that Chidambaram has assumed as the GDP for 2014-2015).

All these numbers are more than the allocation of Rs 1,15,000 crore made by Chidambaram towards food subsidies. This means that there will be trouble for the next government in balancing the budget.

Of course, the new government that takes over after the Lok Sabha elections will present a fresh budget, in which it can junk all the calculations of the current budget (or to put it correctly, the vote of account). But even if the next government does that the expenditure commitments that the Congress-led UPA government has created are so huge, that it will be completely screwed on the finance front, even before it takes over.

This article originally appeared on www.FirstBiz.com on February 17, 2014

Vivek Kaul tweets @kaul_vivek