Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

Over the last few days, there has been a lot of talk in the media about the government considering petroleum subsidy reforms (You can read about it here and here). One of the most well kept secrets in India has been the fact that the end consumer does not get any subsidy on petroleum products. But what we have been told is exactly the opposite.

What we have been told over the years is that the oil marketing companies have been selling products like petrol, diesel, cooking gas and kerosene, at a loss (The price of petrol was deregulated on June 26, 2010, so that is no longer the case). To a large extent, the government compensates the oil marketing companies for this loss. Hence, these products are subsidised. Subsidies are bad and they need to be done away with.

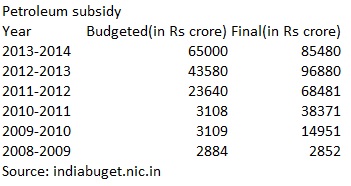

The truth is however a little more nuanced than that. Let’s take a look at the following table.

In 2012-2013, the under-recovery of the oil marketing companies on selling oil products had stood at Rs 1,61,029 crore. Of this the government provided a cash assistance of Rs 1,00,000 crore. Rs 60,000 crore came in from upstream oil companies like ONGC and Oil India Ltd.

So far so good. But does this amount to a subsidy to the end consumer? As Surya P Sethi writes in an article titled “Analysing the Parikh Committee Report on Pricing of Petroleum Products“It is clear that Indian consumers are paying the highest price for lower quality petrol and more for lower quality diesel when compared to the US and Japan – the two most vociferous proponents of removing fuel subsidies. Also, Japan and the UK and, indeed, several other countries tax diesel at a lower rate.”

A major portion of the price that we pay on buying petrol and diesel essentially consists of taxes collected by both the central and the state governments. At the central government level a huge amount of tax on oil products is collected through excise duties. At the state level, the value added tax on petroleum products is the major contributor.

For the calculations here, we will ignore the various taxes collected by the state government on petroleum products. We will consider only taxes earned by the central government. This includes excise duty, customs duty, cess on crude oil, income tax, dividend and dividend distribution tax paid by oil companies, as well as profit from exploration, among other things.

If all this is taken into account for the year 2012-2013 the central government earned Rs 1,17,422 crore. In comparison it paid out Rs 1,00,000 crore in the form of cash assistance to oil marketing companies. That still meant a surplus of Rs 17,422 crore.In 2011-2012, it earned Rs 1,19,850 crore from petroleum products and companies. The cash assistance to oil marketing companies during that year stood at Rs 83,500 crore. That meant a surplus of Rs 36,350 crore.

The scenario looks similar during the first nine months of 2013-2014 as well. The cash assistance to oil marketing companies stood at Rs 35,772 crore. In comparison, the central government had earned Rs 83,619 crore, leading to a surplus of Rs 47,847 crore.

Hence, the end consumer does not get any subsidy on petroleum products as a whole, even though the oil marketing companies suffer huge under-recoveries in the sale of diesel, cooking gas and kerosene.

A criterion that the International Energy Agency uses for defining something as a subsidy is whether it “lowers the price paid by energy consumers.” As A Citizens’ Guide to Energy Security in India points out “consumer subsidies, as the name implies, support the consumption of energy, by lowering prices at which energy products are sold.” That is clearly not the case in India.

Given this, the government and the media should stop using the word subsidy when it comes to talking about petroleum products as a whole. Second, the surplus that the government generates through taxing petroleum products and companies, should actually be paid out as cash assistance to the oil marketing companies. Once, that is done the burden on the upstream oil companies like ONGC and Oil India Ltd, which finance a part of the under-recoveries, will come down.

This is very important given that India imports more than 80% of the oil that it consumes. With the pressure on ONGC to finance the under-recoveries coming down, it can spend more money on exploring for oil. This will go long way towards beefing up the energy security of India.

The trouble is that the surplus that the government makes by taxing petroleum companies and petroleum products goes towards bringing down the fiscal deficit. The fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends.

In fact, once we consider the total amount of taxes earned by the state government the real situation comes to the fore. During the first nine months of 2013-2014, state governments earned Rs 1,01,493 crore from taxing petroleum products. The state governments are highly dependent on these taxes to finance their expenditure. If the price of petroleum products needs to be controlled, it is this dependence that needs to come down. And that is easier said than done.

Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected]

The article originally appeared on www.firstbiz.com on June 15, 2014