A few months back I wrote a series of columns on oil. In these columns, I maintained that it is very difficult to predict the price of oil over the long term, given that there are way too many factors involved, other than just demand for and supply of the commodity. At the same time I said that in the short-term the price of oil will continue to go down. And that is precisely what has happened.

A few months back I wrote a series of columns on oil. In these columns, I maintained that it is very difficult to predict the price of oil over the long term, given that there are way too many factors involved, other than just demand for and supply of the commodity. At the same time I said that in the short-term the price of oil will continue to go down. And that is precisely what has happened.

Data from the Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell (PPAC) tells us that as on December 8, 2015, the price of the Indian basket of crude oil stood at $ 37.34 per barrel. In fact, during the course of this week, oil prices have touched a seven year low.

What is happening here? The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), an oil cartel of some of the biggest oil producers in the world, met last Friday on December 4, 2015.

The statement released by OPEC after the meeting as usual was very general in nature. It said: “emphasizing its commitment to ensuring a long-term stable and balanced oil market for both producers and consumers, the Conference [i.e. OPEC] agreed that Member Countries should continue to closely monitor developments in the coming months.”

What does this “really” mean? In the past, the OPEC has adjusted its oil production depending on oil demand. If the demand was high, it increased production so as to ensure that oil prices did not go up too much. This was done in order to ensure that other forms of energy did not become viable. If the demand was low, it cut production in order to ensure that oil prices did not fall too much.

In the last one year, OPEC has abandoned this strategy primarily on account of all the oil that is being produced by the shale oil companies in the United States. As shale oil started to hit the market, the OPEC countries started to lose market share. Hence, they decided not to cut production any further, and try and maintain market share, even if that meant low oil prices.

The major producers within the OPEC (the likes of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iraq) produce oil at anywhere between $9 to $20 a barrel. It costs anywhere between $29 to $90 per barrel to produce shale oil, as per the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Hence, the idea was to engineer low oil prices and in the process make shale oil unviable and help OPEC countries maintain their market share. Nevertheless, despite low oil prices, the US shale oil industry is not shutting down at the rate it was expected to, when the price of oil started to fall, around a year back.

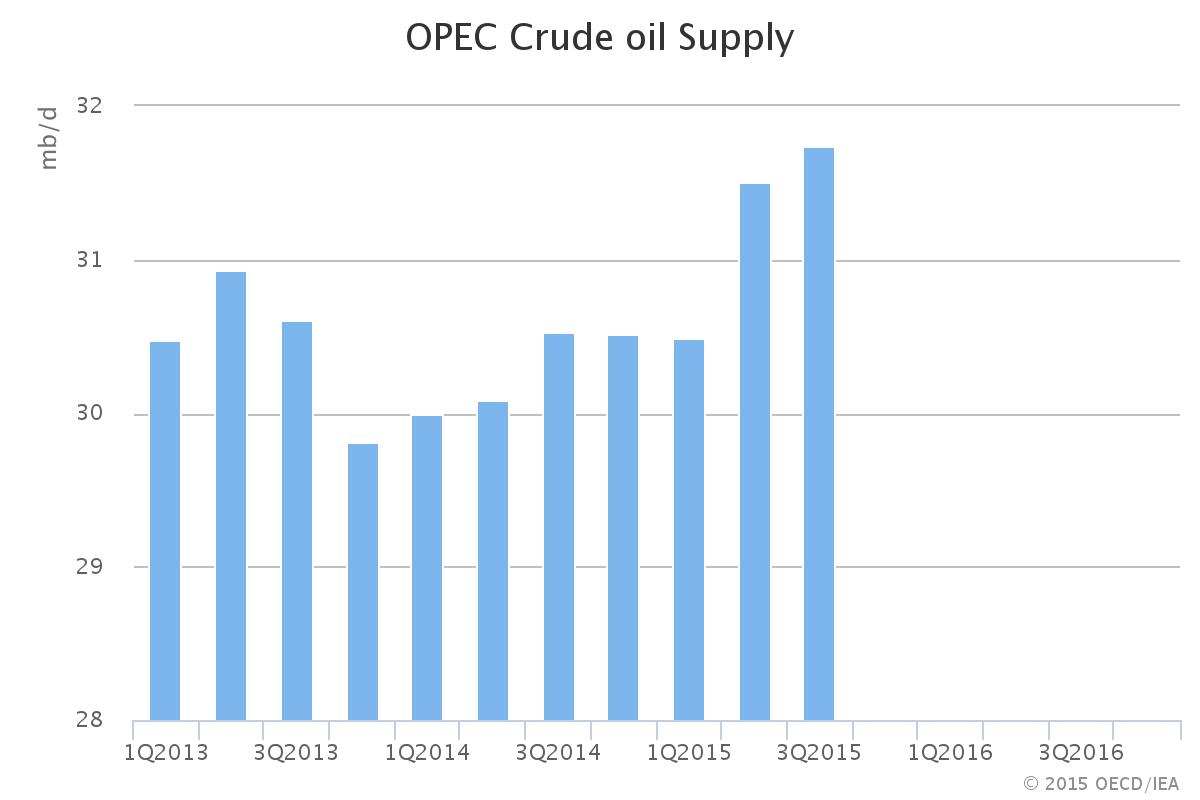

And this explains why OPEC continues to produce oil full blast. It wants to kill the US shale oil industry. Further, what the OPEC’s statement released last Friday really means is that the cartel will maintain its production at over 31.5 million barrels per day. In fact, members of the OPEC have always known to cheat on the side and produce more than their allocated quotas. Hence, the daily production is likely to be more than 31.5 million barrels per day.

As the newsagency Bloomberg reported: “There’s as much as 2 million barrels of oversupply in the market, and OPEC’s meeting on Friday means “everyone does what they want,” Iran’s Oil Minister Bijan Namdar Zanganeh said in Vienna on Dec. 4.”

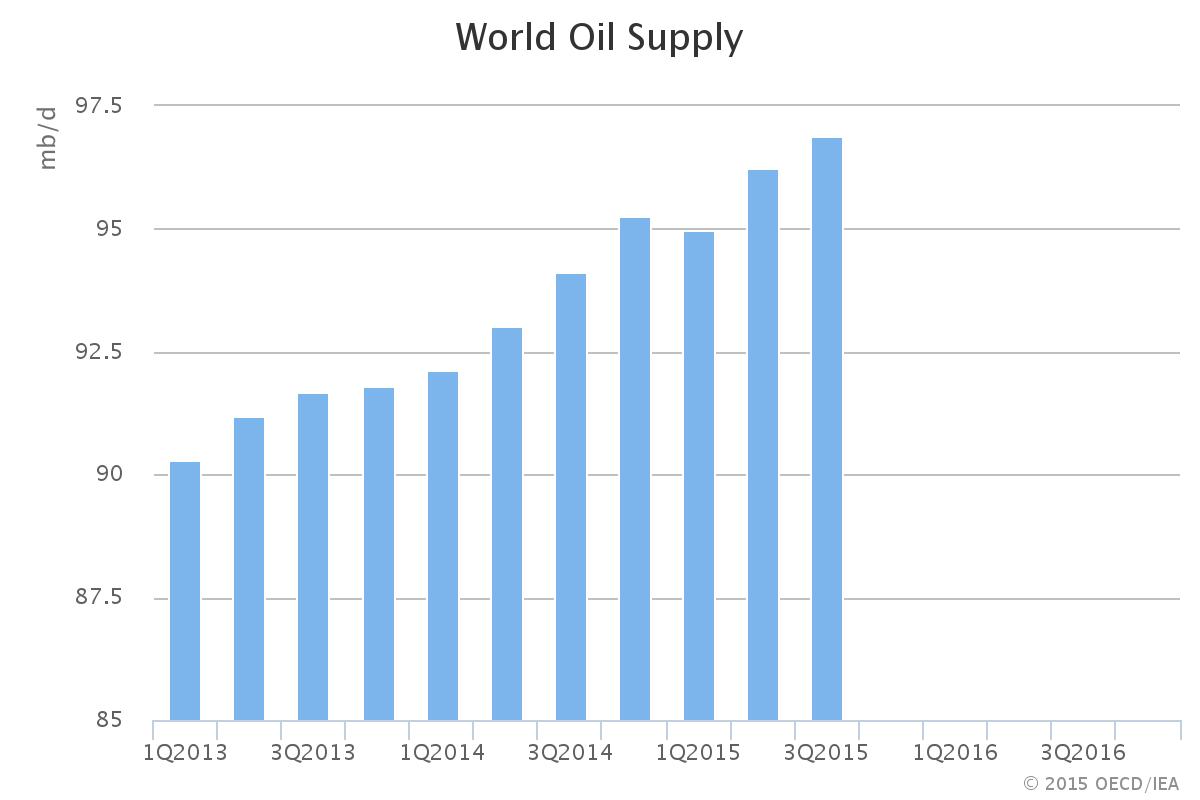

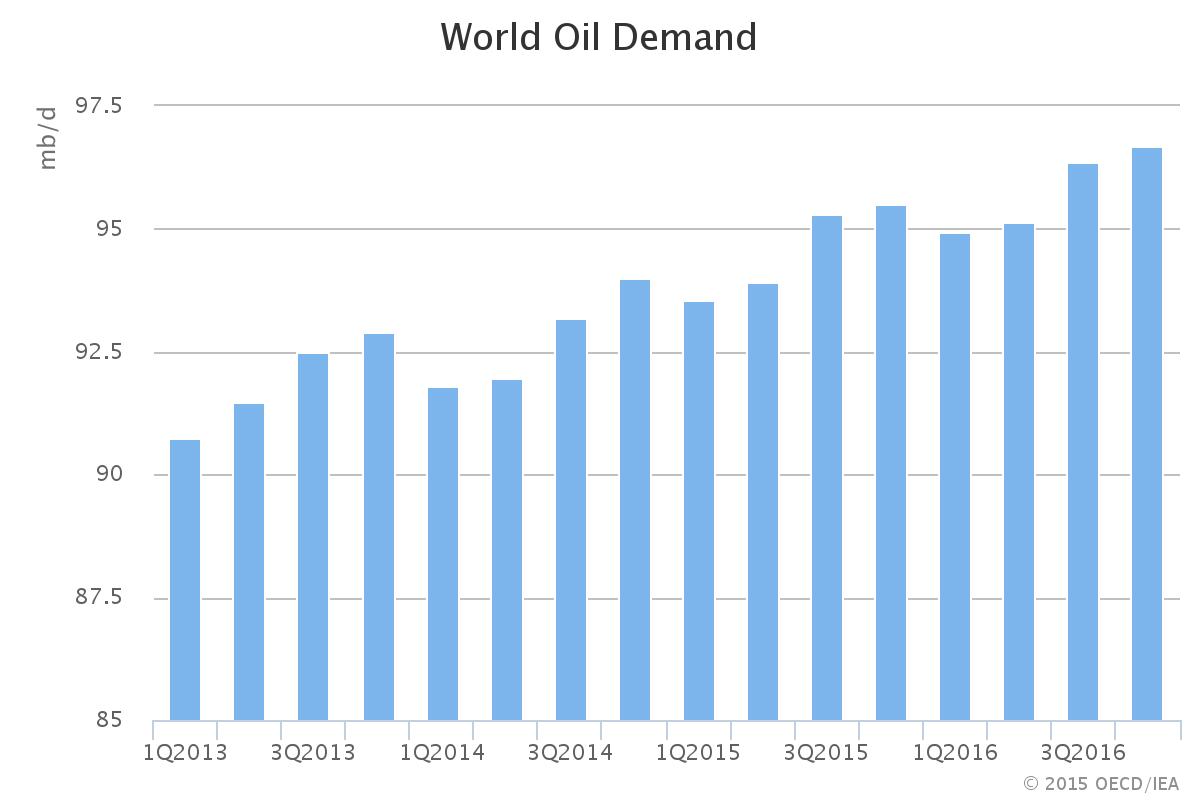

Take a look at the following two charts from the International Energy Agency. One is a chart showing the World Oil Supply. And the other shows World Oil Demand.

As per the chart, the World Oil Supply during the period July to September 2015 was at 96.9 million barrels per day. The demand on the other hand was lower than the supply at 96.35 million barrels per day.

The OPEC oil supply during the period July to September 2015, went up in comparison to the period April to June 2015. The OPEC production between April to June 2015 was at 31.5 million barrels per day. Over the next three months it jumped to 31.74 million barrels per day. Hence, OPEC contributed significantly to the jump in global oil supply.

In fact, the production of OPEC is likely to increase in the months to come as the sanctions on Iran are lifted and the country is allowed to export more oil.

Over and above this, the global oil inventory is at a record high. As a recent IEA report points out: “Stockpiles of oil at a record 3 billion barrels are providing world markets with a degree of comfort. This massive cushion has inflated even as the global oil market adjusts to $50/bbl oil. Demand growth has risen to a five-year high…with India galloping to its fastest pace in more than a decade. But gains in demand have been outpaced by vigorous production from OPEC and resilient non-OPEC supply – with Russian output at a post-Soviet record and likely to remain robust in 2016 as well. The net result is brimming crude oil stocks that offer an unprecedented buffer against geopolitical shocks or unexpected supply disruption.”

As the report further points out: “The stock overhang that first developed in the US on the back of soaring North American crude production, has now spread across the OECD. Since the second quarter, inventories in Asia Oceania have swollen by more than 20 million barrels. In Europe, record high Russian output and rising deliveries from major Middle East exporters are filling the tanks.”

What this clearly means is that oil prices are likely to stay low over the next few months. Further, the forecast is for a fairly mild winter in Europe as well as North America. This means that the demand for diesel, which is the fuel of choice for heating in Europe as well as North East America, is unlikely to go up at a rapid rate. The stockpiles of diesel are at a five-year high.

The column originally appeared on The Daily Reckoning on December 10, 2015