Vivek Kaul

In an interview with the Business Standard in September 2013, Jairam Ramesh was asked why the Congress party was losing ground so badly in urban India. “Because of the bhumihar from Ghazipur,” Ramesh replied. He was referring to the former Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India, Vinod Rai, who had retired from his post in May 2013. The CAG in a series of reports had exposed the wrongdoings of the government.

As Rai writes in Not Just an Accountant—The Diary of the Nation’s Conscience Keeper “Jairam Ramesh was a regular visitor to the CAG headquarters for discussions on the audit of the national rural employment guarantee programme. His discussions did indeed lend value. In one of the conversations with me, he asked why N.K.Singh, the Rajya Sabha MP representing the Janata Dal(United), used to refer to me not only as a bhumihar but as a ‘bhumihar from Ghazipur’. I told him I did know what it meant.” Rai further writes that even his caste was brought into prominence, “and this after sixty-seven years of independence.”

Ramesh’s quip against Rai was a part of a series of statements made by leaders of the Congress party to discredit him. This after, the CAG had meticulously gone about exposing wrongdoings of the government in the telecom, coal, sports and aviation sectors.

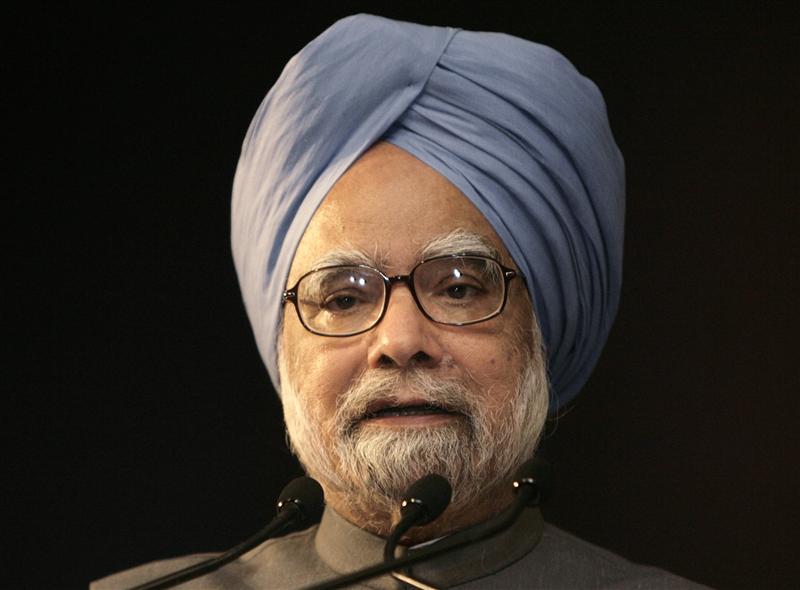

Manish Tewari, the Congress leader who can speak on just about anything, said that the “R-virus has infected the Indian growth story. The R-virus stands for a phenomenon were responsible individuals decide to become loose cannons.” On another occasion Tewari said “When individuals decide to go rogue, institutions suffer. That possibly has the most detrimental effect on the India growth story.” Sharad Pawar, who is a part of the UPA, and was the food and agriculture minister in the UPA government said “CAG has taken certain decisions that have created a different atmosphere in the country… I haven’t seen anything like this in the forty-five years of my career as a politician.” Montek Singh Ahluwalia, the deputy chairman of the Planning Commission, went on to claim that “untrained staff [is] auditing CAG reports.” The business lobby ASSOCHAM even went to the extent of releasing advertisements which said that CAG reports were sending wrong messages. The advertisement went on to state “The CAG’s conclusions over the 57 coal block allotment appear to have been arrived at without taking all facts into consideration. Only one of the 57 blocks has gone into production.”

The then finance minister P Chidambaram even went to the extent of saying that the government had faced no loss from giving away coal blocks free to private and public sector companies. “If coal is not mined, where is the loss? The loss will only occur if coal is sold at a certain price or undervalued,”Chidambaram had said.

In order to understand this statement we need to go back to the early 1990s. The government at that point of time realized that enough coal was not being produced. The Coal Mines(Nationalisation) Act was amended with effect from June 9, 1993. This was done largely on account of the inability of Coal India Ltd (CIL), which produces most of India’s coal, to produce enough coal.

The coal production in 1993-94 was 246.04 million tonnes, up by 3.3% from the previous year. This rate was not going to increase any time soon as newer projects had been hit by delays and cost over-runs, as still often happens in India. As the Economic Survey of 1994-95 pointed out “As on December 31, 1994, out of 71 projects under implementation in the coal sector, 22 projects are bedevilled by time and cost over-runs. On an average, the time over-run per project is about 38 months. There is urgent need to improve project implementation in the coal sector.”

The idea, as the Economic Survey of 1994-1995 pointed out, was to “encourage private sector investment in the coal sector, the Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act, 1973, was amended with effect from June 9, 1993, for operation of captive coal mines by companies engaged in the production of iron and steel, power generation and washing of coal in the private sector.”

The amendment to the Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act 1973 allowed companies which were in the business of producing power and iron and steel, to own coal mines for their captive use. Hence, the coal that these companies produced in these mines was to be used to feed into the production of power and iron and steel. Any excess coal was to be handed over to the local subsidiary of the Coal India Ltd.

Between 1993 and 2011, 195 coal blocks were given away for free to public and private sector companies for captive use. Most of these free coal blocks were given away between 2004 and 2011. Nevertheless even by 2011-2012, these coal blocks produced only 36.9 million tonnes of coal. This amounted to around 6.8% of the total production of 539.94 million tonnes during the course of that year.

And because very little coal was being produced in these captive mines, this led Chidambaram and the industry lobby Assocham to put forward the argument that since coal was not being mined how did the government face any losses? This was a really stupid argument to make. The government handed over a natural asset free to private and public sector players. They, in turn, were not able to mine coal from it quickly enough. How does that mean that the government did not face any losses? It does not change the fact that coal blocks were essentially handed over for free.

As Rai puts it in his book: “I thought any prudent and concerned industry body would have questioned the urgency to allot when the allottees had not even commenced mining. But then, since every person who wanted to display his loyalty to the government was hastening to take potshots at the CAG, why not an industry body?”

Interestingly, Manmohan Singh explained the inability of the private coal producers to start producing coal quickly enough by saying “it is true that the private parties that were allocated captive coal blocks could not achieve their production targets. This could be partly due to the cumbersome processes involved in getting statutory clearances.”

This Rai says is a defeatist argument. As he writes “This does appear to be a defeatist argument; if the government is aware that the processes are cumbersome and accords the process urgency, it is incumbent on the government to take steps to ensure speedy clearances.”

The CAG came in for heavy criticism for coming up with a loss figure of Rs 1,86,000 crore for these coal blocks being given away free by the government. In his book, Rai explains with great clarity how this number was arrived at. The CAG worked with most conservative estimates while coming up with this number. While calculating the loss the CAG did not take into account the coal blocks given to the public sector companies. Only blocks given to private sector companies were taken into account.

The total geological reserves of the coal blocks given away for free amounted to around 44.8 billion tonnes. The total amount of coal in a block is referred to as geological reserve. But not all of it can be extracted. Open cast mining of coal typically goes to a depth of around 250 metres below the ground whereas underground mining goes to a depth of around 600-700 metres. Beyond this, it is difficult to extract coal.

The portion of the geological reserves that can be extracted are referred to as extractable reserves. The CAG worked with fairly conservative estimates on this front as well. Typically extractable reserves are around 80-95% of geological reserves. As Rai writes “Audit based its computation on [the] conservative estimate of 73 million tonnes for every 100 million tonnes given in the GR [geological reserve]…Can audit be faulted if its computation was based on a conservative estimate of 73 per cent?…The extractable reserves…based on the aforementioned method, was found by the CAG to be 6282.5 million tonnes, which is mentioned in the report.”

So only 6282.5 million tonnes of the 44.8 billion tonnes of geological reserves was assumed as extractable reserves while calculating the losses of the government due to giving away coal blocks for free.

After establishing the extractable reserves the CAG needed to establish the price at which this coal could be sold as well as the cost of production of this coal. For establishing the price at which the coal cold be cold, the CAG considered three possible options.

“The first was by imports. The average import price of non-coking coal sourced from Indonesia during 2010-2011 was Rs 3,678 per tonne (Indonesia supplied most of our non-coking coal imports). The second source was the coal sold in e-auction by Northern Coalfields Limited, a subsidiary of CIL [Coal India Ltd] based in Singrauli. The third and major source of coal supply in the country was that which was mined and supplied by CIL. Audit utilized the only creditable data available in the public domain—that of CIL. CIL is regularly audited by the CAG, so its accounts and other details can be taken as authentic. From the audited accounts of 2010-2011, the average sales price of all grades of coal sold by CIL was taken as Rs 1,028 per tonne. This was the most conservative price too,” writes Rai.

After this, the cost of production of coal needed to be established. For this, the CAG again went back to CIL, which produces most of the coal in the country. As Rai writes “The average cost of coal mined by CIL was found to be Rs 583 per tonne. The MoC has indicated, after due verification, that the financing cost ranged from Rs 100 to Rs 150 per tonne. To be on the safe and conservative side, audit assumed it to be at Rs 150. Thus, while the average sale price was Rs 1,028, the average cost was Rs 583 plus Rs 150, namely Rs 733,” writes Rai.

Manmohan Singh later criticized this calculation by saying “the cost of production of coal varies significantly from mine to mine even for CIL due to varying geo-mining conditions, method of extraction, surface features, number of settlements, availability of infrastructure etc.”

By taking the average cost of production these are exactly the factors that CAG was taking into account. And this left Rs 295 per tonne (Rs 1028 minus Rs 733) as the financial benefit. So Rs 295 of financial benefit per tonne was multiplied with 6282.5 million tonnes of extractable reserves and a loss figure of close to Rs 1,86,000 crore was arrived at.

As you can clearly see the most conservative estimates had been used to arrive at a loss number. If the CAG had not used these conservative estimates it could have easily put out a much bigger number for these losses.

Another criticism that the CAG came in for was that the loss calculation did not take the concept of net present value(NPV) into account. “Even if discounting had been done to arrive at the NPV, we would have possibly projected an annual increase of 10 per cent in cost/sale price, and we would then have discounted, at, say, a discount factor of 10 per cent. We would have got to an NPV of financial gain of Rs 2.40 lakh crore, at 11 per cent of Rs 1.86 lakh crore and at 12 per cent of Rs 1.49 lakh crore. There is no substantial difference. Hence, why all the ire?”

In the end, Vinod Rai has had the last laugh. The Supreme Court in a recent decision deemed the allocation of coal blocks to be illegal. And for those who are still not convinced about the way Rai operated as the CAG, it is time they read his book.

The article appeared on www.FirstBiz.com on Sep 16, 2014

(Vivek Kaul is the author of Easy Money. He tweets @kaul_vivek)