Vivek Kaul

In an interview to NDTV, Naveen Jindal , chairman of Jindal Steel and Power, and Congress politician said that his company would not be able to pay the fine imposed by the Supreme Court. “We will not be able to pay it..because we have not made a provision for it,” Jindal said.

Jindal also told the television channel that the Supreme Court decision “was a ‘setback’ for companies which have mined coal for the past 20 years to generate power and make steel, and now been told that what they are doing is illegal, while they have been creating wealth for the country.”

In a decision on September 24, 2014, the Supreme Court had cancelled 204 out of the 218 coal blocks allocated by the government since 1993. The coal blocks were allocated for free for captive mining. Companies which were given these blocks could use the coal to produce power, iron and steel, aluminium, cement etc. The Court has also fined companies at the rate of Rs 295 per tonne for all the coal that they have produced till date and will continue producing till March 31, 2015, when they need to hand over their mines to the government.

Jindal was the biggest beneficiary of the captive coal block allotments, having been given nine blocks in all. Given this, things he has said in the NDTV interview need to be looked at closely.

The first thing Jindal talks about are “companies which have mined coal for twenty years.”

No company has been mining coal for twenty years. Provisional coal statistics released by the Coal Controller Organisation, which is a part of the coal ministry, shows that coal was first mined by the captive coal blocks only in 1997-98. Also, during this year a minuscule amount of 0.71 million tonnes of coal was produced by these mines. The production crossed 10 million tonnes of coal only in 2004-2005, when these blocks produced 10.11 million tonnes. Hence, serious production from these coal mines has happened only for 10 years and not 20 years as Jindal points out. This was primarily because between 1993 and 2002 only 15 blocks had been allocated to private companies.

This maybe nitpicking, nonetheless it is an important factual point to make given the sensitivity of the issue. In Jindal Steel and Power’s case the Gare Palma IV coal block has been operational from February 1999. This coal mine produced 6 million tonnes of coal in 2013-2014 and is expected to produce a similar amount in 2014-2015.

Further, just because something has been happening for many years, doesn’t mean it is right, even though it may have been government policy. The coal blocks were allocated based on the recommendations of an inter ministerial screening committee. The committee was set up in July 1992 and the coal secretary was its chairman.

As Vinod Rai writes in Not Just an Accountant—The Diary of the Nation’s Conscience Keeper “This committee was to scrutinize applications for captive mining and allocate coal blocks for development, subject to statutes governing coal mining, following which the coal minister would approve the allotment…The screening committee is expected to asses applications based on parameters such as the techno-economic feasibility of the end-use project, status of preparedness to set up the end-use project, past track record in executing projects, financial and technical capabilities of applicant companies and the recommendations of the concerned state governments and ministries.”

The committee was supposed to look at each application based on these criteria and then make a decision of who to allot the coal block to. But that doesn’t seem to have happened. As the Supreme Court judgement dated August 25, 2014, clearly points out “The entire exercise of allocation through Screening Committee route thus appears to suffer from the vice of arbitrariness and not following any objective criteria in determining as to who is to be selected or who is not to be selected.”

The judgement further points out that “there is no evaluation of merit and no inter se comparison of the applicants. No chart of evaluation was prepared. The determination of the Screening Committee is apparently subjective as the minutes of the Screening Committee meetings do not show that selection was made after proper assessment. The project preparedness, track record etc., of the applicant company were not objectively kept in view.”

Further, the guidelines that the Screening Committee was supposed to follow did not contain “any objective criterion for determining the merits of the applicants.” “As a matter of fact, no consistent or uniform norms were applied by the Screening Committee to ensure that there was no unfair distribution of coal in the hands of the applicants.” The Supreme Court came to this conclusion after studying the minutes of the Screening Committee meetings.

Interestingly, the Comptroller and Auditor General(CAG) had come to a similar conclusion when it had audited the procedure for allotment of coal locks in mid 2011. As Rai points out “The process that the committee actually followed was not really clear from the records. All that the records showed was that the committee met, deliberated and merely recorded the name of the block allotted to a company, and the state where the end-use plant existed. It is left to the reader to decide if transparency was a victim and, if so, how audit erred in pointing out this lacuna.”

The problem was that even if the Screening Committee wanted to follow objective criteria, at times it was simply not possible. Former coal secretary P C Parakh (who took over as coal secretary in the second week of March 2004) explains this in Crusader or Conspirator—Coalgate and Other Truths “By the time I took charge of the ministry, the number of applicants for each block had increased considerably although still in single digits. I found a number of applicants fulfilling the criteria specified for allocation of each block on offer. This made objective selection extremely difficult.”

In fact in the years to come the situation became much worse as more and more companies applied for coal blocks. As Parakh writes “According to CAG’s report, 108 applications were received for Rampia and Dip Side of Rampia Block [names of two coal blocks]. I found it difficult to make an objective selection when the number of applicants was in single digits. How could the Screening Committee take objective decisions when the number of applicants per block had run into three digits?”

Parakh to his credit realized pretty early that the Screening Committee method of allotment wasn’t working. In fact, in his book Parakh goes on to list several reasons on why giving away coal blocks free for captive mining by companies just did not make sense. By giving away coal blocks for free, companies which had no experience in coal mining were getting into a totally unrelated field. The government had no way of monitoring whether the captive mine was being used for captive use. Or was the company, which had got the coal block, selling the coal it was producing in the open market and thus “promoting corruption and black money”. Further, the system of allocation of coal blocks for free was discriminatory. It offered a huge premium to companies which managed to get a free coal block, in comparison to ones that did not.

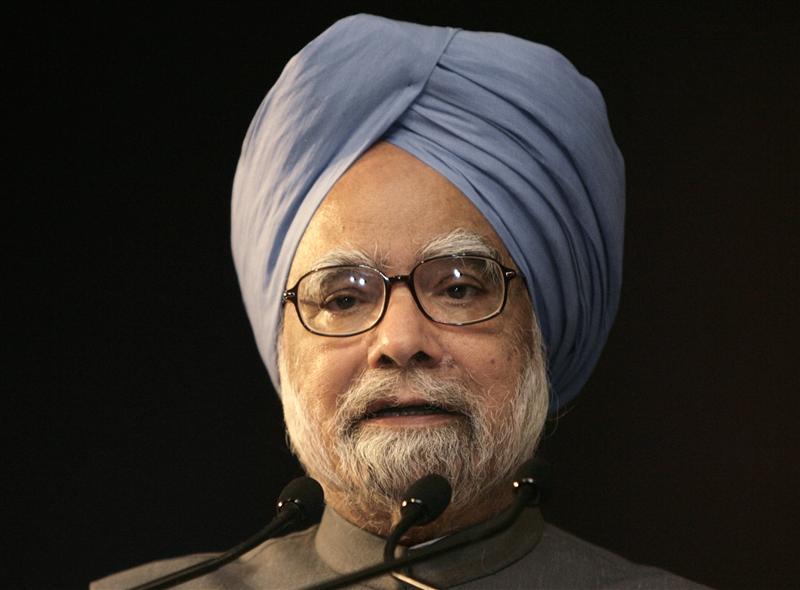

Hence, Parakh proposed to Manmohan Singh(who had taken over as coal minister) in August 2004 that coal blocks should be allotted through the competitive bidding route. Before he did this Parakh had even called an open discussion of all the stakeholders in June 2004.

The stakeholders included the business lobbies FICCI, CII and Assocham, other ministries whose companies had applied for coal blocks and private companies.

Parakh points out that most invitees were not in favour of competitive bidding of coal blocks. As he puts it “not many participants were enthusiastic about open bidding. Their main argument was that the cost of coal to be mined would go up if coal blocks were auctioned.”

Parakh suggests that assuming that business men bidding for coal blocks (if such a process were to be introduced) would drive up the price of coal to astronomical levels is suggesting that they are stupid. As he writes “Participants at open auctions are hard-headed businessmen with an acute sense of profitability. They do not make irrationally high bids. The price at which coal from CIL[Coal India Ltd] was available would automatically put a cap on the bid amount.”

The industry ultimately resisted open bidding simply because until then they had been getting coal blocks for free. And if something is available for free why pay for it. “To an extent, it was a reflection of corporate India’s aversion to transparency,” writes Parakh.

Nevertheless on August 20, 2004, Manmohan Singh approved allocation of coal blocks through the competitive bidding route. Immediately after this a number of letters written by MPs opposing competitive bidding started coming in. As Parakh writes “This included one from Mr Naveen Jindal who had considerable interest in coal mining.”

This is when Dasari Narayana Rao, the famous Telgu film director, who was the minister of state for coal. entered the scene. As Rai points out in his book “Rao, observed that any change in the procedure for the allocation of coal blocks would invite further delay in allocation.”

As Rao wrote while submitting the file to Manmohan Singh: “It is difficult to agree with the view that Screening Committee cannot ensure transparent decision-making. This alone was not adequate ground for switching over to a new mechanism, particularly when the interests of core infrastructure areas are involved.”

On March 25, 2005, Manmohan Singh “recorded the approval of the cabinet note seeking sanction of the competitive bidding system,” Rai points out. But Rao still did not give up and kept talking about the “cost implications” of the competitive bidding system of allocation of coal blocks. He finally succeeded and on July 25, 2005, it was decided that the coal ministry would continue to allot coal to blocks through the Screening Committee route.

In May 2014 the enforcement directorate slapped money laundering charges against Rao and Jindal. As the PTI reported “The agency, according to sources, has framed the charges after it found multi-layered transactions between the firms owned by Jindal to Rao’s firms based in Hyderabad and “illegal money” was routed for alleged favours given for the allocation of coal firms to Jindal.”

Interestingly Jindal told NDTV that “one of the Jindal companies had lent money to an unrelated company, which in turn invested in a company in which the Mr Rao had a controlling stake.”

Given this, the situation is not as simplistic as Jindal tried to project in his NDTV interview. Also, between the Supreme Court and the CAG it has been clearly established that the Screening Committee route to allot coal blocks was not transparent at all and companies which got coal blocks benefited from this lack of transparency. Given this, it led to the Supreme Court cancelling 204 out of the 218 blocks that had been allocated, including coal mines which were already under operation.

Jindal in his interview also told NDTV that his company won’t be able to pay the fine imposed by the Supreme Court because they hadn’t made a provision for it. The Supreme Court has fined the companies already operating coal blocks Rs 295 per tonne for all the coal that they have produced till now and all the coal they will continue to produce till March 31, 2015, when they need to hand over the mines back to the government. This in a way took care of what Parakh termed as discriminatory. As he writes “The [Screening Committee] system of allocation of captive [coal] blocks offers huge advantage to industries that get coal blocks over those who are not able to get coal blocks.”

Edelweiss Securities estimates that Jindal Steel and Power will have to pay a fine of close to Rs 3000 crore. While the company may not have made a provision to pay the fine, it needs to be pointed out that as on March 31, 2014, the company had a balance sheet size of Rs 74,072.1 crore. Its reserves and surplus amounted to Rs 22,519 crore. It had cash and bank balances of Rs 1,015.28 crore. Further, in the last two financial years it has made a total profit of Rs 4820.5 crore.

Also, let’s calculate the financial benefit arising out of the Gare Palma IV coal block which as pointed out earlier has been operational from February 1999. This coal mine produced 6 million tonnes of coal in 2013-2014 and is expected to produce a similar amount in 2014-2015.

A research report brought out by Kotak Institutional Equities suggests that it costs Rs 600-800 per tonne to produce captive coal. In comparison, it costs Rs 3,500 per tonne to import coal. Hence, imported coal is four to five times more expensive than captive coal.

So the cost of producing 12 million tonnes of coal over a two year period at the upper end cost of Rs 800 per tonne would have been Rs 960 crore. Along with a fine of Rs 295 per tonne this amounts to Rs 1314 crore. Consider the other possibility of importing coal at Rs 3500 per tonne. This would have cost the company Rs 4200 crore. The difference between these two numbers comes to Rs 2886 crore. This calculation just takes the last two years into account. Nevertheless the mine has been functioning for close to 15 years now.

The total fine that the company needs to pay amounts to around Rs 3000 crore. Hence, even after it pays the fine the company would have managed to save a lot of money over the years because it got the coal block for free through a process which wasn’t transparent at all.

In fact, Jindal isn’t the only one protesting. The pink papers over the last few days have been full of quotes criticizing the Supreme Court’s decision to cancel the coal block allocations. But when a process has not been transparent for 20 years, it needs to be cancelled. And when this happens, there are bound to be repercussions, which the incumbents won’t like.

As the American author Upton Sinclair once wrote “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it!” The corporates and their lobbies who are coming out against the Supreme Court’s decision are a good example of this.

It needs to be pointed out here that only 40 out of 218 coal blocks are currently operational. Companies, given that they had got blocks for free, seemed to be in no hurry to start production. That wouldn’t have been the case, had they paid for it in the first place.

To conclude, it is worth quoting what Raghuram Rajan and Luigi Zingales write in Saving Capitalism from the Capitalists “Since a person may be powerful because of his past accomplishments or inheritance rather than his current abilities, the powerful have a reason to fear markets…Those in power – the incumbents – prefer to stay in power.” Jindal clearly would have liked that.

The article originally appeared on www.FirstBiz.com on Sep 28, 2014

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

If Bollywood like Hollywood made political biopics, and if things hadn’t turned out the way they have, the story of the former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh would have made for a reasonably good movie.

If Bollywood like Hollywood made political biopics, and if things hadn’t turned out the way they have, the story of the former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh would have made for a reasonably good movie.