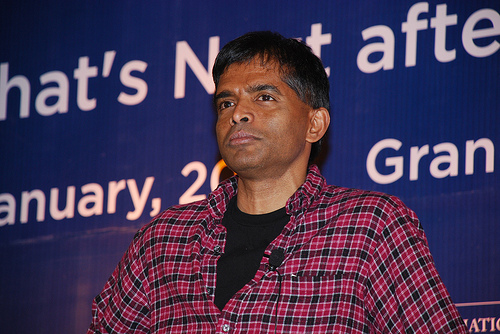

Have you ever heard someone call equity a short term investment class? Chances are no. “I have always had this notion for many years that people buy equities because they like to be excited. It’s not just about the returns they make out of it… You can build a case for equities on a three year basis. But long term investing is all rubbish, I have never believed in it,” says Shankar Sharma, vice-chairman & joint managing director, First Global. In this freewheeling

interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul.

Six months into the year, what’s your take on equities now?

Globally markets are looking terrible, particularly emerging markets. Just about every major country you can think of is stalling in terms of growth. And I don’t see how that can ever come back to the go-go years of 2003-2007. The excesses are going to take an incredible amount of time to work their way out. They are not even prepared to work off the excesses, so that’s the other problem.

Why do you say that?

If you look at the pattern in the European elections the incumbents lost because they were trying to push for austerity. And the more leftist parties have come to power. Now leftists are usually the more austere end of the political spectrum. But they have been voted to power, paradoxically, because they are promising less austerity. All the major nations in the world are democracies barring China. And that’s the whole problem. You can’t push through austerity that easily in a democracy, but that is what is really needed. Even China cannot push through austerity because of a powder-keg social situation. And I find it very strange when people criticise India for subsidies and all that. India is far less profligate than many nations including China.

Can you elaborate on that?

Every country has to subsidise, be it farm subsidies in the West or manufacturing subsidies in China, because ultimately whether you are a capitalist or a communist, people are people. They don’t necessarily change their views depending on which political ideology is at the centre. They ultimately want freebies and handouts. In a country like India, they don’t even want handouts they just want subsistence, given the level of poverty. The only thing that you can do with subsidies is to figure out how to control them. But a lot of it is really out of your control. If you have a global inflation in food prices or oil prices you are not increasing the quantum in volume terms of the subsidy. But because of price inflation, the number inflates. So why blame India? I find it absurd that the Financial Times or the Economist are perennially anti-India. They just isolate India and say that it has got wasteful expenditure programmes. A lot of countries hide things. India, unfortunately, is far more transparent in its reporting. It is easy to pick holes when you are transparent. China gives no transparency so people assume that whatever is inside the black box must be okay. That said, I firmly believe the UID program, when fully implemented, will make subsidies go lower by cutting out bogus recipients.

If increased austerity is not a solution, where does that leave us?

Increased austerity, while that is a solution, it is not achievable. If that is not possible what is the solution? You then have a continual stream of increasing debt in one form or the other, keep calling it a variety of names. But you just keep kicking the can down the road for somebody else to deal with it as long as the voter is happy. Given this, I don’t see how you can have any resurgence. Risk appetite is what drives equity markets. Otherwise you and I would be buying bonds all the time. In today’s environment and in the foreseeable future, we are overfed with risk. Where is the appetite to take more risk and go, buy equities?

So are you suggesting that people won’t be buying stocks?

Well you can get pretty good returns in fixed income. Instead of buying emerging-market stocks if you buy bonds of good companies, you can get 6-7% dollar yield, and if you leverage yourself two times or something, you are talking about annual returns of 14-15% dollar returns. You can’t beat that by buying equities, boss! Even if you did beat that by buying equities, let’s say you made 20%, it is not a predictable 20%, which has been my case for a long time against equities. Equities are a western fashion. I have always had this notion for many years that people buy equities because they like to be excited. It’s not just about the returns they make out of it: it is about the whole entertainment quotient attached to stock investing that drives investors. There is 24-hour television. Tickers. Cocktail discussions. Compared with that, bonds are so boring and uncool. Purely financially, shorn of all hype, equities have never been able to build a case for themselves on a ten-year return basis. You can build a case for equities on a three-year basis. But long-term investing is all rubbish, I have never believed in it.

So investing regularly in equities, doing SIPs, buying Ulips, doesn’t make sense?

I don’t buy the whole logic of long-term equity investing because equity investing comes with a huge volatility attached to it. People just say “equities have beaten bonds”. But even in India they have not. Also people never adjust for the volatility of equity returns. So if you make 15% in equity and let’s say, in a country like India, you make 10% in bonds – that’s about what you might have averaged over a 15-20 year period because in the 1990s we had far higher interest rates. Interest rates have now climbed back to that kind of level of 9-10%. Divide that by the standard deviation of the returns and you will never find a good case for equities over a long-term period. So equity is actually a short-term instrument. Anybody who tells you otherwise is really bluffing you. All the fancy graphs and charts are rubbish.

Are they?

Yes. They are all massaged with sort of selective use of data to present a certain picture because it’s a huge industry which feeds off it globally. So you have brokers like us. You have investment bankers. You have distributors. We all feed off this. Ultimately we are a burden on the investor, and a greater burden on society — which is also why I believe that the best days of financial services is behind us: the market simply won’t pay such high costs for such little value added. Whatever little return that the little guy gets is taken away by guys like us. How is the investor ever going to make money, adjusted for volatility, adjusted for the huge cost imposed on him to access the equity markets? It just doesn’t add up. The customer never owns a yacht. And separately, I firmly believe making money in the markets is largely a game of luck. Even the best investors, including Buffet, have a strike rate of no more than 50-60% right calls. Would you entrust your life to a surgeon with that sort of success rate?! You’d be nuts to do that. So why should we revere gurus who do just about as well as a coin-flipper. Which is why I am always mystified why so many fund managers are so arrogant. We mistake luck for competence all the time. Making money requires plain luck. But hanging onto that money is where you require skill. So the way I look at it is that I was lucky that I got 25 good years in this equity investing game thanks to Alan Greenspan who came in the eighties and pumped up the whole global appetite for risk. Those days are gone. I doubt if you are going to see a broad bull market emerging in equities for a while to come.

And this is true for both the developing and the developed world?

If anything it is truer for the developing world because as it is, emerging market investors are more risk-averse than the developed-world investors. We see too much of risk in our day to day lives and so we want security when it comes to our financial investing. Investing in equity is a mindset. That when I am secure, I have got good visibility of my future, be it employment or business or taxes, when all those things are set, then I say okay, now I can take some risk in life. But look across emerging markets, look at Brazil’s history, look at Russia’s history, look at India’s history, look at China’s history, do you think citizens of any of these countries can say I have had a great time for years now? That life has been nice and peaceful? I have a good house with a good job with two kids playing in the lawn with a picket fence? Sorry, boss, that has never happened.

And the developed world is different?

It’s exactly the opposite in the west. Rightly or wrongly, they have been given a lifestyle which was not sustainable, as we now know. But for the period it sustained, it kind of bred a certain amount of risk-taking because life was very secure. The economy was doing well. You had two cars in the garage. You had two cute little kids playing in the lawn. Good community life. Lots of eating places. You were bred to believe that life is going to be good so hence hey, take some risk with your capital.

The government also encouraged risk taking?

The government and Wall Street are in bed in the US. People were forced to invest in equities under the pretext that equities will beat bonds. They did for a while. Nevertheless, if you go back thirty years to 1982, when the last bull market in stocks started in the United States and look at returns since then, bonds have beaten equities. But who does all this math? And Americans are naturally more gullible to hype. But now western investors and individuals are now going to think like us. Last ten years have been bad for them and the next ten years look even worse. Their appetite for risk has further diminished because their picket fences, their houses all got mortgaged. Now they know that it was not an American dream, it was an American nightmare.

At the beginning of the year you said that the stock market in India will do really well…

At the beginning of the year our view was that this would be a breakaway year for India versus the emerging market pack. In terms of nominal returns India is up 13%. Brazil is down 3%. China is down, Russia is also down. The 13% return would not be that notable if everything was up 15% and we were up 25%. But right now, we are in a bear market and in that context, a 13-15% outperformance cannot be scoffed off at.

What about the rupee? Your thesis was that it will appreciate…

Let me explain why I made that argument. We were very bearish on China at the beginning of the year. Obviously when you are bearish on China, you have to be bearish on commodities. When you are bearish on commodities then Russia and Brazil also suffer. In fact, it is my view that Russia, China, Brazil are secular shorts, and so are industrial commodities: we can put multi-year shorts on them. So that’s the easy part of the analysis. The other part is that those weaknesses help India because we are consumers of commodities at the margin. The only fly in the ointment was the rupee. I still maintain that by the end of the year you are going to see a vastly stronger rupee. I believe it will be Rs 44-45 against the dollar. Or if you are going to say that is too optimistic may be Rs 47-48. But I don’t think it’s going to be Rs 60-65 or anything like that. At the beginning of the year our view that oil prices will be sharply lower. That time we were trading at around $105-110 per barrel. Our view was that this year we would see oil prices of around $65-75. So we almost got to $77 per barrel (Nymex). We have bounced back a bit. But that’s okay. Our view still remains that you will see oil prices being vastly lower this year and next year as well, which is again great news for India. Gold imports, which form a large part of the current account deficit, shorn of it, we have a current account deficit of around 1.5% of the GDP or maybe 1%. We imported around $60 billion or so of gold last year. Our call was that people would not be buying as much gold this year as they did last year. And so far the data suggests that gold imports are down sharply.

So there is less appetite for gold?

Yes. In rupee terms the price of gold has actually gone up. So there is far less appetite for gold. I was in Dubai recently which is a big gold trading centre. It has been an absolute massacre there with Indians not buying as much gold as they did last year. Oil and gold being major constituents of the current account deficit our argument was that both of those numbers are going to be better this year than last year. Based on these facts, a 55/$ exchange rate against the dollar is not sustainable in my view. The underlyings have changed. I don’t think the current situation can sustain and the rupee has to strengthen. And strengthen to Rs 44, 45 or 46, somewhere in that continuum, during the course of the year. Imagine what that does to the equity market. That has a big, big effect because then foreign investors sitting in the sidelines start to play catch-up.

Does the fiscal deficit worry you?

It is not the deficit that matters, but the resultant debt that is taken on to finance the deficit. India’s debt to GDP ratio has been superb over the last 8-9 years. Yes, we have got persistent deficits throughout but our debt to GDP ratio was 90-95% in 2003, that’s down to maybe 65% now. So explain that to me? The point is that as long as the deficit fuels growth, that growth fuels tax collections, those tax collections go and give you better revenues, the virtuous cycle of a deficit should result in a better debt to GDP situation. India’s deficit has actually contributed to the lowering of the debt burden on the national exchequer. The interest payments were 50% of the budgetary receipts 7-8 years back. Now they are about 32-33%. So you have basically freed up 17% of the inflows and this the government has diverted to social schemes. And these social schemes end up producing good revenues for a lot of Indian companies. The growth for fast-moving consumer goods, mobile telephony, two wheelers and even Maruti cars, largely comes from semi-urban, semi-rural or even rural India.

What are you trying to suggest?

This growth is coming from social schemes being run by the government. These schemes have pushed more money in the hands of people. They go out and consume more. Because remember that they are marginal people and there is a lot of pent-up desire to consume. So when they get money they don’t actually save it, they consume it. That has driven the bottomlines of all FMCG and rural serving companies. And, interestingly, rural serving companies are high-tax paying companies. Bajaj Auto, Hindustan Lever or ITC pay near-full taxes, if not full taxes. This is a great thing because you are pushing money into the hands of the rural consumer. The rural consumer consumes from companies which are full taxpayers. That boosts government revenues. So if you boost consumption it boosts your overall fiscal situation. It’s a wonderful virtuous cycle — I cannot criticise it at all. What has happened in past two years is not representative. It is only because of the higher oil prices and food prices that the fiscal deficit has gone up.

What is your take on interest rates?

I have been very critical of the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) policies in the last two years or so. We were running at 8-8.5% economic growth last year. Growth, particularly in the last two or three years, has been worth its weight in gold. In a global economic boom, an economic growth of 8%, 7% or 9% doesn’t really matter. But when the world is slowing down, in fact growth in large parts of the world has turned negative, to kill that growth by raising the interest rate is inhuman. It is almost like a sin. And they killed it under the very lofty ideal that we will tame inflation by killing growth. But if you have got a matriculation degree, you will understand that India’s inflation has got nothing to do with RBI’s policies. Your inflation is largely international commodity price driven. Your local interest rate policies have got nothing to do with that. We have seen that inflation has remained stubbornly high no matter what Mint Street has done. You should have understood this one commonsensical thing. In fact, growth is the only antidote to inflation in a country like India. When you have economic growth, average salaries and wages, kind of lead that. So if your nominal growth is 15%, you will 10-20% salary and wage hikes – we have seen that in the growth years in India. Then you have more purchasing power left in the hands of the consumer to deal with increased price of dal or milk or chicken or whatever it is. If the wage hikes don’t happen, you are leaving less purchasing power in the hands of people. And wage hikes won’t happen if you have killed economic growth. I would look at it in a completely different way. The RBI has to be pro-growth because they no control of inflation.

So they basically need to cut the repo rate?

They have to.

But will that have an impact? Because ultimately the government is the major borrower in the market right now…

Look, again, this is something that I said last year — that it is very easy to kill growth but to bring it back again is a superhuman task because life is only about momentum. The laws of physics say that you have to put in a lot of effort to get a stalled car going, yaar. But if it was going at a moderate pace, to accelerate is not a big issue. We have killed that whole momentum. And remember that 5-6%, economic growth, in my view, is a disastrous situation for a country like India. You can’t say we are still growing. 8% was good. 9% was great. But 4-5% is almost stalling speed for an economy of our kind. So in my view the car is at a standstill. Now you need to be very aggressive on a variety of fronts be it government policy or monetary policy.

What about the government borrowings?

The government’s job has been made easy by the RBI by slowing down credit growth. There are not many competing borrowers from the same pool of money that the government borrows from. So far, indications are that the government will be able to get what it wants without disturbing the overall borrowing environment substantially. Overall bond yields in India will go sharply lower given the slowdown in credit growth. So in a strange sort of way the government’s ability to borrow has been enhanced by the RBI’s policy of killing growth. I always say that India is a land of Gods. We have 33 crore Gods and Goddesses. They find a way to solve our problems.

So how long is it likely to take for the interest rates to come down?

The interest rate cycle has peaked out. I don’t think we are going to see any hikes for a long time to come. And we should see aggressive cuts in the repo rate this year. Another 150 basis points, I would not rule out. Manmohan Singh might have just put in the ears of Subbarao that it’s about time that you woke up and smelt the coffee. You have no control over inflation. But you have control over growth, at least peripherally. At least do what you can do, instead of chasing after what you can’t do.

Manmohan Singh in his role as a finance minister is being advised by C Rangarajan, Montek Singh Ahulwalia and Kaushik Basu. How do you see that going?

I find that economists don’t do basic maths or basic financial analysis of macro data. Again, to give you the example of the fiscal deficit and I am no economist. All I kept hearing was fiscal deficit, fiscal deficit, fiscal deficit. I asked my economist: screw this number and show me how the debt situation in India has panned out. And when I saw that number, I said: what are people talking about? If your debt to GDP is down by a third, why are people focused on the intermediate number? But none of these economists I ever heard them say that India’s debt to GDP ratio is down. I wrote to all of them, please, for God’s sake, start talking about it. Then I heard Kaushik Basu talk about it. If a fool like me can figure this out, you are doing this macro stuff 24×7. You should have had this as a headline all the time. But did you ever hear of this? Hence I am not really impressed who come from abroad and try to advise us. But be that as it may it is better to have them than an IAS officer doing it. I will take this.

You talked about equity being a short-term investment class. So which stocks should an Indian investor be betting his money right now?

I am optimistic about India within the context of a very troubled global situation. And I do believe that it’s not just about equity markets but as a nation we are destined for greatness. You can shut down the equity markets and India would still be doing what it is supposed to do. But coming from you I find it a little strange…

I have always believed that equity markets are good for intermediaries like us. And I am not cribbing. It’s been good to me. But I have to be honest. I have made a lot of money in this business doesn’t mean all investors have made a lot of money. At least we can be honest about it. But that said, I am optimistic about Indian equities this year. We will do well in a very, very tough year. At the beginning of the year, I thought we will go to an all-time high. I still see the market going up 10-15% from the current levels.

So basically you see the Sensex at around 19,000?

At the beginning of the year, you would have taken it when the Sensex was at 15,000 levels. Again, we have to adjust our sights downwards. A drought angle has come up which I think is a very troublesome situation. And that’s very recent. In light of that I do think we will still do okay, it will definitely not be at the new high situation.

What stocks are you bullish on?

We had been bearish on infrastructure for a very long time, from the top of the market in 2007 till the bottom in December last year. We changed our view in December and January on stocks like L&T, Jaiprakash Industries and IVRCL. Even though the businesses are not, by and large, of good quality — I am not a big believer in buying quality businesses. I don’t believe that any business can remain a quality business for a very long period of time. Everything has a shelf life. Every business looks quality at a given point of time and then people come and arbitrage away the returns. So there are no permanent themes. And we continue to like these stocks. We have liked PSU banks a lot this year, because we see bond yields falling sharply this year.

Aren’t bad loans a huge concern with these banks?

There is a company in Delhi — I won’t name it. This company has been through 3-4 four corporate debt restructurings. It is going to return the loans in the next year or two. If this company can pay back, there is no problem of NPAs, boss. The loans are not bogus loans without any asset backing. There are a lot of assets. At the end of every large project there is something called real estate. All those projects were set up with Rs 5 lakh per acre kind of pricing for land. Prices are now Rs 50 lakh per acre or Rs 1 crore or Rs 1.5 crore per acre. If nothing else, dismantle the damn plant, you will get enough money from the real estate to repay the loans of the public sector banks. So I am not at all concerned on the debt part. If the promoter finds that is going to happen, he will find some money to pay the bank and keep the real estate.

On the same note, do you see Vijay Mallya surviving?

100% he will survive. And Kingfisher must survive, because you can’t only have crap airlines like Jet and British Airways. If God ever wanted to fly on earth, he would have flown Kingfisher.

So he will find the money?

Of course! At worst, if United Spirits gets sold, that’s a stock that can double or triple from here. I am very optimistic about United Spirits. Be it the business or just on the technical factor that if Mallya is unable to repay and his stake is put up for sale, you will find bidders from all over the world converging.

So you are talking about the stock and not Mallya?

Haan to Mallya will find a way to survive. Indian promoters are great survivors. We as a nation are great survivors.

How do you see gold?

I don’t have a strong view on gold. I don’t understand it well enough to make big call on gold, even though I am an Indian. One thing I do know is that our fascination with gold has very strong economic moorings. We should credit Indians for having figured out what is a multi century asset class. Indians have figured out that equities are a fashionable thing meant for the Nariman Points of the world, but for us what has worked for the last 2000 years is what is going to work for the next 2000 years.

What about the paper money system, how do you see that?

I don’t think anything very drastic where the paper money system goes out of the window and we find some other ways to do business with each. Or at least I don’t think it will happen in my life time. But it’s a nice cute notion to keep dreaming about.

At least all the gold bugs keep talking about the collapse of the paper money system…

I know. I don’t think it’s going to happen. But I don’t think that needs to happen for gold to remain fashionable. I don’t think the two things are necessarily correlated. I think just the notion of that happening is good enough to keep gold prices high.

(A slightly smaller version of the interview appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on July 31,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/money/interview_you-can-shut-the-equity-market-india-would-still-be-doing-fine_1721939)

(Interviewer Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])