In the budget speech he made on February 28, 2015, the finance minister Arun Jaitley had said: “I intend to begin this process this year by setting up a Public Debt Management Agency (PDMA) which will bring both India’s external borrowings and domestic debt under one roof.”

The government of India, like most governments spends more than it earns. The difference it makes up through borrowing. This borrowing is currently managed by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). Jaitley now wants to take away this responsibility from the RBI and set up an independent public debt management agency.

On the face of it this sounds like a simple move-one institution was taking care of the government borrowings needs, now the government wants to takeover the responsibility. But it is not as simple as that.

Before I explain why, it is important to understand something known as the statutory liquidity ratio (SLR), which currently stands at 21.5%. What this means is that for every Rs 100 that banks raise as a deposit, Rs 21.5 needs to be invested in government bonds.

This number was at higher levels earlier and has constantly been brought down by the RBI over the years. This provision helps the government raise money at lower interest rates than it would otherwise be able to.

This is something that the Report of the Expert Committee to Revise and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework (better known as the Urjit Patel committee) released in January 2014 pointed out: “Large government market borrowing has been supported by regulatory prescriptions under which most financial institutions in India, including banks, are statutorily required to invest a certain portion of their specified liabilities in government securities and/or maintain a statutory liquidity ratio (SLR).”

This statutory requirement essentially ensures that there is a constant demand for government bonds. This helps the government get away by offering a lower rate of interest on its bonds.

“The SLR prescription provides a captive market for government securities and helps to artificially suppress the cost of borrowing for the Government, dampening the transmission of interest rate changes across the term structure,” the Expert Committee report points out.

Take a look at the following chart. Between 2007-2008 and 2013-2014, the government was able to borrow money at a much lower rate of interest than the prevailing inflation. The red line which represent the estimated average cost of public debt (i.e. Interest paid on government borrowings) has been below the green line which represents the consumer price inflation, since around 2007-2008.

|

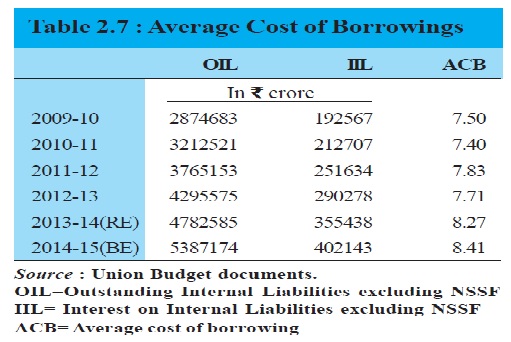

The major reason for the same is the fact that there is an inbuilt demand for government securities. The Economic Survey of 2014-2015 has some interesting data which buttresses the point that I am trying to make. The total internal liabilities of the government of India have gone up by 1.9 times between 2009-10 and 2014-2015. Nevertheless, the average cost of borrowing has gone up only from 7.5% to 8.41%.

This financial repression of forcing banks, insurance companies as well as provident funds to buy government bonds, allows the government to raise money at low interest rates, than they would be able to do if they allowed the market to operate.

Now the government wants to take away the debt management function from the RBI and raise money independently. In this scenario the question is can the SLR continue? Dr YV Reddy, former governor of the RBI, made this point in an interview to the The Economic Times. As he said: “If the government is having an independent debt office then how can the statutory liquidity ratio of a high order continue. Once it is an independent debt office, basically, it should independently be able to raise money.”

Fair point, I guess. “So, if the government want to raise money then indirectly the regulator cannot go on supporting through a cell. So the pre-condition will be SLR has to be removed. Because it would be inappropriate to say that you are independent but I will help you do something. So, in all probability the RBI will have no choice except to reduce SLR to zero as a precondition for an independent debt office,” Reddy told The Economic Times.

The question that crops up here is whether the government is ready to take on this risk given that it is likely to lead to higher interest rates. With banks no longer having to compulsorily buy government bonds, they may not buy government bonds all the time, like is the case currently. This will lead to a situation where the government will have to offer a higher interest rate to get the banks interested. While this sounds good on the face of it, given that if the government offers higher interest rates on its bonds, that higher interest rate will become the benchmark.

Given this, banks will have to offer higher interest rates on their fixed deposits. This means that the chances of savers getting a higher rate of interest (which is greater than the rate of inflation) also goes up.

But if banks offer a higher rate of interest on fixed deposits, they will also have to charge a higher rate of interest on their loans. And this is something that the government won’t like, given that it is currently trying to push down interest rates in the hope of getting the investment cycle and the consumption cycle going all over again. It needs to be pointed out that savers are not the ones either governments or politicians are really bothered about.

Nevertheless, the government might force the RBI to keep the SLR at its current level. But then there would be no independent public debt office. It would be a farce. As Reddy put it: “If the government is pressurising the RBI to not reduce the SLR that is inappropriate. That is not an independent debt office. And it would be inappropriate for RBI even to appear to support the government debt programme. It cannot appear to be.”

Long story short-we haven’t heard the last of this issue. There will be more to come in the time to come. Stay tuned.

The column originally appeared on The Daily Reckoning on Mar 14, 2015