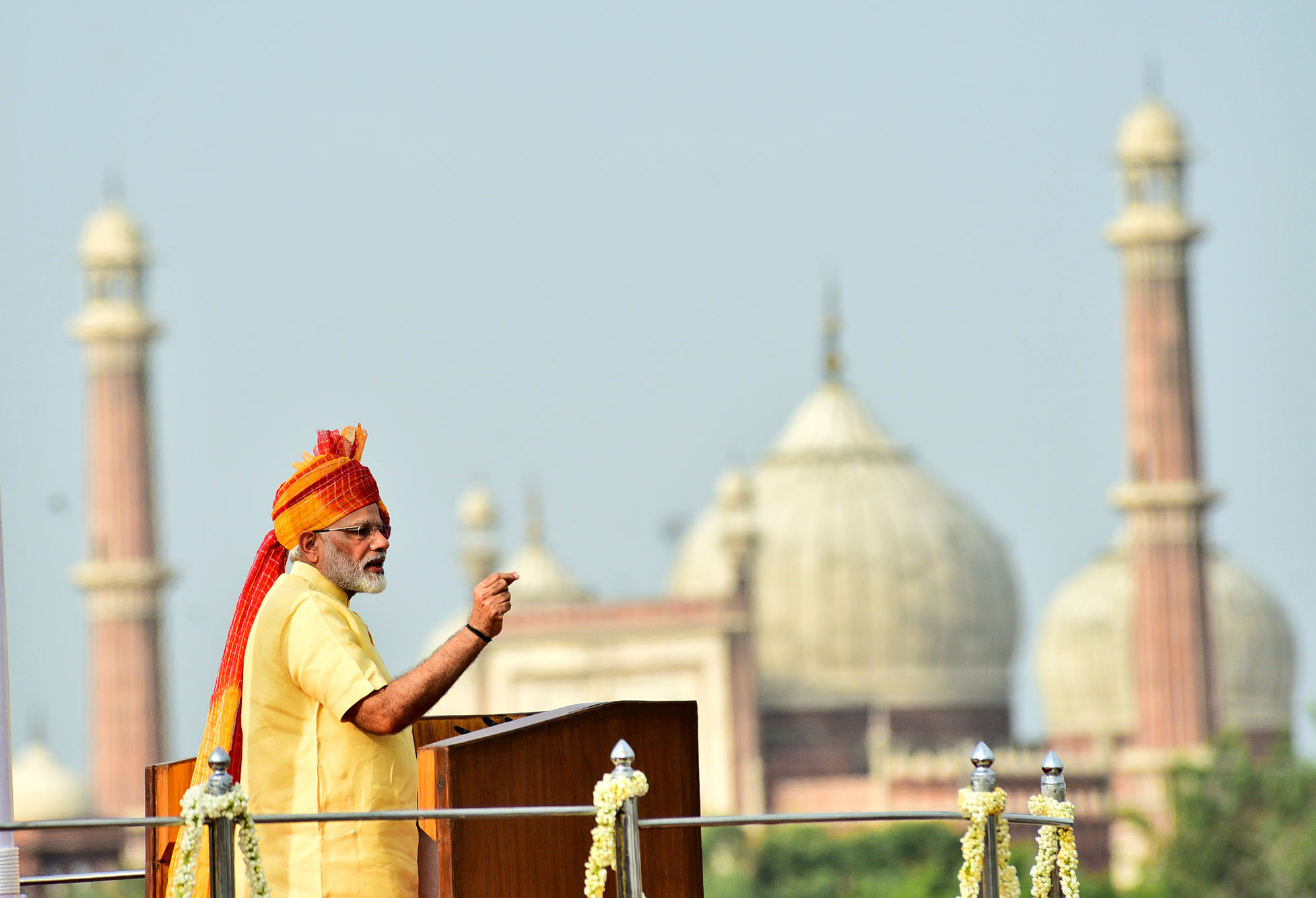

Narendra Modi, took over as the prime minister of the country on May 26, 2014. On that day, the global price of the Indian basket of crude oil was $108.05 per barrel. Back then, one litre of petrol cost Rs 80 in Mumbai. Diesel in the city was being sold at Rs 65.21 per litre.

Three years have gone by since then and meanwhile, the global oil scenario has changed completely. On September 14, 2017, the price of Indian basket of crude oil was at $54.56 per barrel, around half of what it was when Modi took over as prime minister.

At Rs 79.5 per litre, the price of petrol in Mumbai as on September 14, 2017, in Mumbai, was more or less same as it was when Modi took over as prime minister. Diesel at Rs 62.46 per litre was slightly lower.

What is happening here? While, the price of crude oil has halved, the price of petrol and diesel, which are by-products of crude oil, continues to remain more or less the same (This argument may not hold all across the country, given that different states levy different taxes and different rates of taxes on petrol and diesel).

The gain because of fall in price of oil, has been captured majorly by the central government and the state governments, by increasing the different taxes that are levied on petrol and diesel. Lately, the commission given to pumps which sell petrol and diesel, has also gone up.

A small-scale industry has emerged lately, trying to defend the high taxes that consumers pay on petrol and diesel. Here are the arguments on offer:

a) India imports 80 per cent of the oil that it consumes. Given this, prices of petrol and diesel need to be high, in order to discourage people from consuming more and more of it. The assumption is that at lower price levels, people will consume more petrol and diesel.

b) We need to respect the environment. Petrol and diesel pollute the environment, and hence, taxes on petrol and diesel need to be high.

c) The high taxes on petrol and diesel have helped the government bring down its fiscal deficit without having to cut on its expenditure. This is something that is required in an economic environment where growth is slowing down and hence, government spending needs to be strong. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends.

d) High taxes on petrol and diesel help the government earn enough money in order to fund the physical infrastructure that the country badly needs.

e) High petrol and diesel prices push demand towards more fuel-efficient cars. Also, by taxing petrol more than diesel, the government is ensuring that the private modes of transport (which largely use petrol) are taxed more than the public modes of transport (which use diesel).

f) The oil marketing companies need the flexibility to price their products on a day to day basis. It is this flexibility that reflects in the healthy valuations that their stocks currently enjoy in the stock market.

g) High taxes help the government finance the oil marketing companies which can then sell domestic cooking gas and kerosene at lower prices.

Each of these arguments is largely correct (I mean just because a small scale industry has emerged, doesn’t mean they are wrong) except for the last one. The subsidies on domestic cooking gas and kerosene are now down to around Rs 25,000 crore, which isn’t much in comparison to the petroleum subsidy of the past years. Hence, high taxes on petrol and diesel are clearly not required to fund the subsidy.

But there is one point that these economic commentators and analysts do not talk about. High taxes on the petrol and diesel makes the government lazy and helps it to continue favouring the status quo. Allow me to elaborate. It is worth remembering here that money is fungible. Just as high taxes on petrol and diesel allow the government to fund physical infrastructure, they also allow it to do a lot of other things that a government shouldn’t be doing. Let’s look at the points one by one:

a) Between 2010-2011 and 2015-2016, Air India has lost close to Rs. 35,000 crore, and yet it continues to be run. The losses are not surprising, given that the airline business is a very competitive business and the government clearly doesn’t have the wherewithal to run it. The question is where does the money to keep bankrolling Air India come from? The high taxes on petrol and diesel.

Lately, there has been talk of selling the airline. Let’s see, if and when that happens.

b) Or take the case of Hindustan Photo Films Manufacturing Company Ltd. It is the fourth largest loss-making company among the loss making public sector units. It made losses of Rs 2,528 crore in 2015-201 Between 2004-2005 and 2015-2016, the company has made losses of close to Rs 15,000 crore. As mentioned earlier in 2015-2016, the company lost Rs 2,528 crore. It employed 217 individuals. This meant a loss of Rs 11.65 crore per employee. Where does the money to run this company come from?

c) In total, high taxes on petrol and diesel allowed the government to run 78 loss making public sector enterprises in 2015-2016. Between 2011-2012 and 2015-2016, the loss making public sector enterprises have made losses of Rs 1,33,400 crore. Where is the money to finance these losses coming from?

d) Between 2009 and now, the government has spent roughly around Rs 1,50,000 crore, recapitalising public sector banks. The public sector banks have a humungous bad loans portfolio, as they keep writing off the bad loans, their shareholders’ equity keeps coming down and the government as the largest owner, needs to recapitalise them. Bad loans are essentially loans in which the repayment from a borrower has been due for 90 days or more. Take a look at Table 1.

Table 1:

| Gross non-performing advances ratio | |

| Indian Overseas Bank | 24.99% |

| IDBI Ltd. | 23.45% |

| Central Bank of India | 19.55% |

| UCO Bank | 18.83% |

| Bank of Maharashtra | 18.00% |

| Dena Bank | 17.39% |

| United Bank of India | 16.56% |

| Oriental Bank of Commerce | 14.49% |

| Bank of India | 14.20% |

| Allahabad Bank | 13.72% |

| Punjab National Bank | 13.20% |

| Andhra Bank | 12.91% |

| Corporation Bank | 12.14% |

| Union Bank of India | 11.77% |

| Bank of Baroda | 11.15% |

| Punjab & Sind Bank | 10.80% |

| Canara Bank | 10.00% |

Source: Author calculations on Indian Banks’ Association data.

As on March 31, 2017.

Table 1 tells us that 17 public sector banks have a bad loans ratio of 10 per cent or high. This basically means that of every Rs 100 of loans that they have given, a tenth or more, is not being repaid. The government currently owns 21 banks, after the merger of the associate banks of State Bank of India and the Bhartiya Mahila Bank, with the State Bank of India.

Some of these banks like the Indian Overseas Bank are in a particularly bad state. This bank has a bad loans ratio of close to 25 per cent i.e. one fourth of its loans have been defaulted on.

Where is the money to keep these banks going, coming from? In a world where money wasn’t free flowing because of high taxes on petrol and diesel, banks like the Indian Overseas Bank, UCO Bank, United Bank of India, Dena Bank, etc., would have already been shutdown or perhaps been sold off. These banks are too small on the lending front to make any substantial difference to the total lending carried out by banks in India. But their losses do hurt the government a lot. Every extra rupee that goes towards funding these banks is taken away from something more important areas like education, health and agriculture.

e) Also, given the different taxes implemented by different states, the price of petrol and diesel tend to vary across the country. Take the case of the government of Maharashtra charging a drought cess of Rs 9 every time one litre of petrol is bought in the state. Why is this cess even there during a time when there is really no drought in the state? It is just an easy way for the government to raise money. Most people don’t even know that they are paying for something like this, every time they buy petrol.

Hence, to introduce a sense of equality among citizens living in different states, petrol and diesel need to be taxed under the GST (They are already a part of it, with zero percent tax rates).

The high taxes from petrol and diesel also helps the government to continue running many inefficient firms as well as banks. Any plan of closing down these firms and banks is likely to met with a lot resistance and also, lead to a lot of hungama (for the lack of a better word). Given this, it makes sense for the government to take the easy way out, maintain the status quo and continue running these firms and banks.

As Donald J Boudreaux writes in The Essential Hayek: “People’s intense focus on their interests as producers, and their relative inattention to their interests as consumers, leads to press for government policies that promote and protect the interests of producers.”

Any idea of shutting down or selling an inefficient public sector enterprise or banks, is likely to be met with a lot of protests from the employees as well as the trade unions representing them. The political parties are likely to join in. Hence, it is easy for the government to maintain the status quo and not make any difficult decisions.

But the money that goes towards keeping these individuals happy, is taken away from other areas like education, agriculture, health etc. People who lose out because of this, do not have the kind of representation that people working for government run firms have.

Of course, all this does not mean that there should be no taxes on petrol and diesel. With the right to govern comes the right to tax people. But these taxes should be at a reasonable level. Also, with lower taxes, people will spend more money on personal consumption and that will help economic growth. And the impact of people spending money, on economic growth, is always greater than that of the government.

To conclude, it is worth remembering that every coin has two sides, and it doesn’t always land up heads.

A slightly different version of this column appeared on Pragati on September 19, 2017.