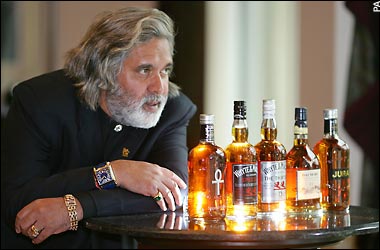

A few days back sections of the media reported that Vijay Mallya, a part-time businessman and a full-time defaulter of bank loans, had celebrated his sixtieth birthday by throwing a huge party at the Kingfisher Villa in Candolim, Goa.

As the Mumbai Mirror reported: “International pop icon Enrique Iglesias belted out his 2014 chartbuster ‘Bailando’ (Dancing) hours after Sonu Nigam completed a nonstop two-hour session with ‘Tum jiyo hazaron saal, saal ke din ho pachaas hazaar’.”

This is while banks wait to recover thousands of crore of loans that Mallya has defaulted on, in his quest to own and run an airline.

While Mallya and other industrialists continue to have a good time, the bad loans of banks continue piling up. The Mid-Year Economic Analysis released by the ministry of finance last week points out towards the same. As it points out: “Gross Non Performing Assets (NPAs) of scheduled commercial banks, especially Public Sector Banks (PSBs) have shown an increase during recent years.”

The total bad loans (gross non-performing assets) of scheduled commercial banks increased to 5.14 % of total advances as on September 30, 2015. The number had stood at 4.6% of total advances, as on March 31, 2015. This means a jump of 54 basis points in a period of just six months. One basis point is one hundredth of a percentage.

The situation is much worse in public sector banks. The total bad loans of public sector banks stood at 6.21% of total advances as of September 30, 2015. This number had stood at 5.43% as on March 31, 2015. This is a huge jump of 78 basis points, within a short period of six months. The number had been at 4.72% as on March 31, 2014. This tells us very clearly that the bad loans situation of public sector banks has clearly worsened.

In fact, we get the real picture if we look at the stressed assets of public sector banks. The stressed asset number is obtained by adding the bad loans and the restructured assets of a bank. A restructured asset is an asset on which the interest rate charged by the bank to the borrower has been lowered. Or the borrower has been given more time to repay the loan i.e. the tenure of the loan has been increased. In both cases the bank has to bear a loss.

The stressed assets of the public sector banks as on September 30, 2015, stood at 14.2% of the total advances. Hence, for every Rs 100 of loans given by public sector banks, Rs 14.2 are currently in dodgy territory. In March 2015, the stressed assets ratio was at 13.15%. This is a significant jump of 105 basis points. In fact, if we look at older data there are other inferences that we can draw.

In March 2011, the number was at 6.6%. In March 2012, the number grew to 8.8%. And now it stands at 14.2%. What does this tell us? It tells us very clearly that banks are increasingly restructuring more and more of their loans and pushing up the stressed asset ratio in the process. And that is not a good thing. The banks are essentially kicking the can down the road in the hope of avoiding to have to recognise bad loans as of now.

In a research note published earlier this year, Crisil Research estimates that 40% of the loans restructured during 2011-2014 have become bad loans. Morgan Stanley estimates that 65% of restructured loans will turn bad in the time to come. What this tells us very clearly tells us that a major portion of stressed assets are essentially restructured loans which haven’t been recognised as bad loans.

This clearly tells us that the balance sheets of public sector banks continue to remain stressed. Data from the Indian Banks’ Association shows that the public sector banks own a total of 77.4% of assets of the total banking system. This means they dominate the system. And if their balance sheets are in a bad shape it is but natural that they will go slow on giving ‘new’ loans. As the latest RBI Annual Report points out: “Private sector banks with lower NPA ratios, posted higher credit growth …At the aggregate level, the NPA ratio and credit growth exhibited a statistically significant negative correlation of 0.8, based on quarterly data since 2010-11.”

As the accompanying chart clearly points out the loan growth of private sector banks which have a lower amount of stressed assets has been much faster than that of public sector banks.

Source: RBI Annual Report

Source: RBI Annual Report

Also, it is worth asking here why are public sector banks continuing to pile up bad loans. The answer might perhaps lie in the fact that the interest paying capacity and the principal repaying capacity of corporates who have taken on these loans continues to remain weak. As the Mid-Year Economic Review points out: “Corporate balance sheets remain highly stressed. According to analysis done by Credit Suisse, for non – financial corporate sector (based on ~ 11000 companies in the CMIE database as of FY2014 and projections done for FY2015 based on a sample of 3700 companies), the number of companies whose interest cover is less than 1 has not declined significantly (this number was 1003 in September 2014 and is 994 in September 2015 quarter).”

Interest coverage ratio is arrived at by dividing the operating profit (earnings before interest and taxes) of a company by the total amount of interest that a company needs to pay on what it has borrowed during a given period. An interest coverage ratio of less than one, as is the case with many companies in the Credit Suisse sample, essentially means that the companies are not making enough money to even be able to pay interest on their borrowings.

Further, “the weighted average interest cover ratio has declined from 2.5 in September 2014 to 2.3 in September 2015 (research indicates that an interest cover of below 2.5 for larger companies and below 4 for smaller companies is considered below investment grade).”

Given this, it is not surprising that bad loans of banks continue to pile up, while guys like Mallya continue to have a “good time”.

Postscript: I will be taking a break from writing The Daily Reckoning for the next few days. Will see you again in the new year. Here is wishing you a Merry Christmas and a very Happy New Year.

The column originally appeared on The Daily Reckoning on December 24, 2015