The Economic Survey for 2016-2017 was released yesterday. The Survey has a chapter on demonetisation and makes some very interesting points which I want to discuss in today’s piece.

One of the reasons offered for the Modi government carrying out demonetisation is: “Across the globe there is a link between cash and nefarious : the higher the amount of cash in circulation, the greater the amount of corruption, as measured by Transparency International.”

The Survey further points out: “In this sense, attempts to reduce the cash in an economy could have important long-term benefits in terms of reducing levels of corruption. Yet India is “off the line”, meaning that its cash in circulation is relatively high for its level of corruption.”

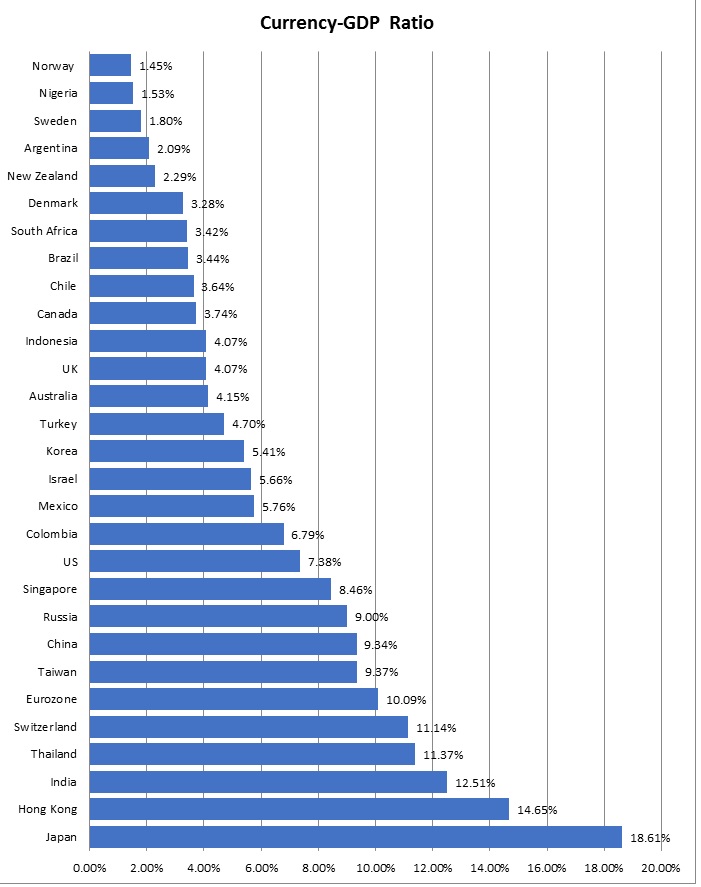

Is this really true? Is there a link between the total cash in the economy and corruption? Let’s take a look at the currency to gross domestic product(GDP) ratio across countries for 2015.

Source: The Curse of Cash, Kenneth Rogoff, http://scholar.harvard.edu/rogoff/curse_of_cash_data

As can be seen from the above table, India’s currency to GDP ratio is quite high at 12.51 per cent. But Japan’s is even higher at 18.61 per cent. What rank does Japan hold in the Transparency International’s corruption ranking? In 2015, Japan was the 18th least corrupt country in the world. Where did India stand? India was the 76th least corrupt country in the world.

Hence, Japan which has a higher currency to GDP ratio than India is significantly less corrupt than India is. This basically means that cash is a greater part of the Japanese economy than it is of the Indian economy, but still the Japanese are less corrupt than the Indians. This goes totally against the point made in the Economic Survey.

Also, Japan is not an outlying one-off example. Take the case of Brazil. The currency to GDP ratio in this case is 3.44 per cent. This is nearly one-fourth the Indian ratio of 12.51 per cent. This means that Brazil has largely moved away from cash or currency as a form of payment. Nevertheless, does that mean that Brazil is less corrupt? As per Transparency International data Brazil is also the 76th least corrupt country in the world, like India is.

There are other examples as well. At 1.45 per cent, the currency to GDP ratio is the lowest in Norway. At 1.53 per cent Nigeria comes in next. Norway is the fifth least corrupt country in the world. On the other hand, Nigeria is the 136th least corrupt country in the world.

Let me give you more examples. After Norway and Nigeria, come Sweden, Argentina, New Zealand and Denmark, when it comes to low currency to GDP ratio. Sweden is the third least corrupt country in the world. New Zealand is the fourth least and Denmark is the least corrupt country in the world. But Argentina comes in at 107th, much lower than even India, despite having a very low currency to GDP ratio.

Are we done yet? Colombia has a currency to GDP ratio of 6.79 per cent, which is significantly lower than that of India. But it is the 83rd least corrupt country in the world. Or take the case of Singapore, which has a reasonably high currency to GDP ratio of 8.46 per cent, but it is the eight least corrupt country in the world, as per Transparency International.

How about China? China’s currency to GDP ratio at 9.34 per cent is lower than that of India. But it is the 83rd least corrupt country in the world, a little below India at 76th position.

All these examples clearly show that there is no clear link between high cash in the economy and the prevailing corruption in the country. And even if there is a link, it is a very weak one. Given this, what do we say about the Economic Survey’s observation? To put it simply, the Economic Survey is published by the ministry of finance, which is a part of the government. Hence, not surprisingly, it is trying to bat for the government on the demonetisation front.

What else does the Economic Survey have to say on demonetisation? On page 55 it points out: “A cautionary word is in order. India’s demonetisation is unprecedented, representing a structural break from the past. This means that forecasting its impact is hazardous.”

This is a very interesting statement. What the Economic Survey is essentially saying here is that forecasting the impact of demonetisation can be hazardous. Why is that? This, for the simple reason that there is no past example of demonetisation in a country being carried out in a situation, like that of India.

As the Survey points out on Page 54: “India’s demonetisation is unprecedented in international economic history, in that it combined secrecy and suddenness amidst normal economic and political conditions. All other sudden demonetisations have occurred in the context of hyperinflation, wars, political upheavals, or other extreme circumstances.”

Given this unique context, it is risky and dangerous (other meanings of the world hazardous) to forecast the impact of demonetisation. If this is the case, it is worth asking on what basis did the government make the decision to demonetise high denomination notes, given that forecasting its impact is not easy at all. Or so the Economic Survey published by the Ministry of Finance tells us. Further, after warning the readers that forecasting the impact of demonetisation is hazardous, the Survey goes about making several forecasts (on pages 59-60).

Such silly blemishes that bat for the government, spoil what is otherwise a well-written Survey.