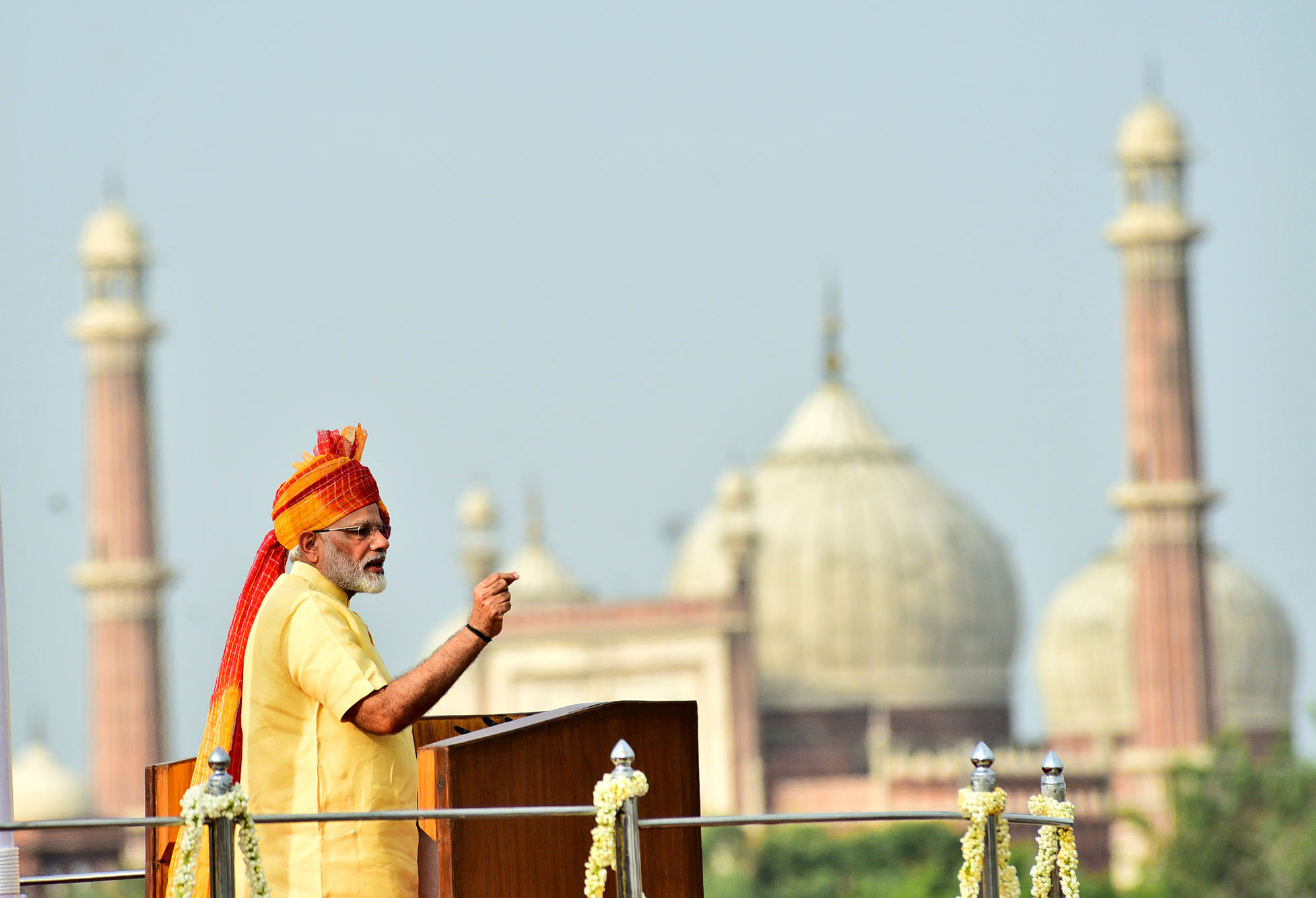

In a speech last week, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, offered several data points to tell his fellow countrymen, that all is well with the Indian economy. And those who didn’t think so were essentially being needlessly pessimistic, he suggested.

Now only if he had bothered to look at data points beyond those he chose to offer, a totally different situation would have emerged. In this piece, I offer many data points to show that all is not well with the Indian economy.

1) Let’s start with the loans disbursed by banks during the course of this year. Let’s look at non-food credit to start with. These are the loans given out by banks after we have adjusted for food credit or loans given to the Food Corporation of India and other state procurement agencies, for buying rice and wheat directly from farmers at the minimum support price (MSP) for the public distribution system. Take a look at Figure 1.

Figure 1:

The Figure 1 clearly shows that the total amount of non-food credit given by banks during the course of this year has been in negative territory. This basically means that on the whole banks haven’t given a single rupee of a loan. The situation is the worse it has been in five years. Non-food credit consists of loans given to agriculture, industry, services and retail sectors, respectively.

Let’s take a look at each of these sectors.

2) Let’s take a look at Figure 2, which plots the loans given by banks to agriculture and allied activities.

Figure 2:

Loans given to agriculture and allied activities are in negative territory during the course of this year. Again, this basically means that on the whole banks haven’t given a single rupee of a loan to agriculture. In technical terms, their loan book to agriculture has shrunk. Is this possibly because of farm loans being waived off by state governments, that only time will tell.

3) Let’s take a look at Figure 3, which plots the loans given banks to industry.

Figure 3:

Figure 3 makes it clear that loans given to industry by banks continue to shrink. This isn’t surprising given the huge amount of bad loans accumulated by banks on lending to industry. Banks still don’t trust the industry.

4) Let’s take a look at Figure 4, which plots the loans given by banks to the services sector.

Figure 4:

This comes in as a major surprise, loans given to services have shrunk majorly during this financial year. Services constitute half of the Indian economy. If the firms operating in this sector are not interested in borrowing, then how can the Indian economy possibly be doing well?

5) Let’s take a look at Figure 5, which plots the retail loans given by banks during this financial year.

Figure 5:

Retail loans are the only loans which have been in positive territory during the course of this year. Nevertheless, they have been more or less at the same level over the last few years.

This, despite the fact that interest rates have come down dramatically. If people are not willing to borrow more even at lower interest rates, how can things be alright with the Indian economy, is a question well worth asking.

Sadly, Prime Minister Modi, did not include any of these data points in his speech and presentation.

6) The latest Consumer Confidence Survey of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) for September 2017, states: “Households’ current perceptions on the general economic situation remained in the pessimistic zone for four successive quarters, with the outlook worsening… The employment situation has been the biggest cause of worry for respondents, with sentiment plunging further into the pessimistic zone; the outlook on employment has also weakened.”

7) Take a look at Figure 6, which plots the cement production over the years.

Figure 6:

Cement production is down this year, in comparison to the previous year. This tells us clearly that the construction and the real estate industry continue to be in trouble. These industries are huge employers of people, especially those who have low-skills.

8) The commissioning of new projects has slowed down. As Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, which tracks this data, points out: “Projects worth Rs 512 billion were commissioned during the quarter ended September 2017. In the coming weeks this estimate is expected to rise. It could reach about Rs 700 billion. Even if this happens, this would be the lowest commissioning of projects during the Modi government’s tenure so far.”

9) There has been a fall in new investment proposals. As Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, which tracks this data, points out: “Projects worth Rs.845 billion were proposed during the quarter ended September 2017. This is the lowest level of intentions to invest seen in a quarter during the tenure of the Modi government.”

10) There has been a huge fall in the profit of companies. As Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy points out: “We infer this and other related nuggets of information from the financial statements of 1,127 listed companies… Profit before taxes of these companies fell by 27.9 per cent over their level a year ago.”

11) Take a look at Figure 7, which plots the trade deficit or the difference between exports and imports.

Figure 7:

The trade deficit has jumped up majorly during the course of this financial year. This as I have explained beforehas primarily been on account of a jump in non-oil non gold non silver imports, in the aftermath of demonetisation. The unseen negative effects of demonetisation continue to impact the economy.

12) The growth in private consumption expenditure is at a six-quarter low. As the RBI Monetary Policy Statement pointed out: “Of the constituents of aggregate demand, growth in private consumption expenditure was at a six-quarter low in Q1 of 2017-18 [April to June 2017].”

13) As the RBI Monetary Policy Statement further pointed out: “India’s export growth continued to be lower than that of other emerging economies such as Brazil, Indonesia, South Korea, Turkey and Vietnam, some of which have benefited from the global commodity price rebound.”

14) Take a look at Figure 8 which plots the investment to GDP ratio.

Figure 8:

The investment to GDP ratio has improved a little in the period of three months ending June 2017, but it continues to remain very low. As the RBI Monetary Policy Statement pointed out: “The implementation of the GST so far also appears to have had an adverse impact, rendering prospects for the manufacturing sector uncertain in the short term. This may further delay the revival of investment activity, which is already hampered by stressed balance sheets of banks and corporates.”

15) Now let’s take a look at Figure 9, which plots the growth of the non-government part of the GDP.

Figure 9:

Figure 9 basically plots the growth of the non-government part of the economy, which typically constitutes 87 to 92 per cent of the economy. The growth of the non-government part of the economy has fallen to around a little over 4 per cent. This extremely important detail did not find a place anywhere in Prime Minister Modi’s speech.

If the non-government part of the economy is growing at such a slow rate, how will jobs for the one million youth entering the workforce every month, ever be created.

16) The situation becomes even more worrisome if we look at Figure 10.

Figure 10:

As is clear from Figure 10, the growth rate of industry in general and manufacturing and construction in particular is at a five-year low. The manufacturing part of industry grew at 1.17 per cent during April to June 2017, whereas construction grew by 2 per cent during the same period.

This is a big reason to worry simply because manufacturing and construction have the potential to create new jobs. An estimate made by Crisil Research suggests that in construction 12 workers are typically required to create Rs 10 lakh worth of output. In case of manufacturing it is seven workers.

17) Take a look at Figure 11, which basically shows that labour intensive sectors have slowed down between January to June 2017.

Figure 11:

As Crisil Research points out in a recent research note: “In the past two quarters, three sectors have grown much faster than GDP: 1) Trade, hotels, transport, communication and services related to broadcasting; 2) Electricity, gas, water supply and other utilities, and 3) Public administration, defence and other services. Of these, only the trade, hotels and restaurants sub-sector is labour intensive, requiring about 6 workers to produce Rs 10 lakh worth of output. But the share of this sub-sector in total output is low at ~12%. In contrast, a fast growing sector like public administration, defence and other personal services, despite having a larger share in output, has low labour intensity of only 3. And sectors with higher labour intensity – such as construction (12) and manufacturing (7) – have been undershooting overall GDP growth.”

It needs to be said here that public administration, defence and other personal services sector is basically a proxy for the government. And the government has stopped creating jobs.

18) Take a look at Figure 12.

Figure 12:

Figure 12 plots the index of industrial production (IIP), a measure of the industrial activity in the country. It also plots manufacturing, which forms more than three-fourths of IIP. The growth of both these measures has been in low single digits for a while now and is clearly a reason to worry.

19) Take a look at Figure 13, which basically plots the consumption of petroleum products, over the years.

Figure 13:

The consumption of petroleum products has more or less been flat in comparison to the last financial year. This is another good indicator of slowing economic growth.

20) Take a look at Figure 14, which plots the sale of commercial vehicles during the course of this financial year.

Figure 14:

Commercial vehicle sales, which are a very good indicator of a pick-up in the industrial part of the economy. Commercial vehicle sales this year were lower than they were last year.

21) Take a look at Figure 15. It plots the fiscal deficit ratio of the government over the years.

Figure 15:

As can be seen from Figure 15, in the first five months of the current financial year, 96 per cent of the annual fiscal deficit has already been crossed. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends. Why is the fiscal deficit during the first five months of the year at such a high level? The answer lies in the fact that the economic growth is slowing down and the government is trying to drive up growth, by spending more.

22) Take a look at Figure 16.

Figure 16:

It tells us that the increase in government expenditure has been a greater part of the increase in GDP over the last two years. For the period April to June 2015, the increase in government expenditure made up for around 1.3 per cent of the increase in GDP during that period. Since then it has jumped to 39.2 per cent between January to March 2017 and 34.1 per cent between April to June 2017.

So, the government is spending more and more in order to drive economic growth. This again shows that the government in its actions does believe that the economic growth is slowing down, but PM Modi won’t say so in his public posturing.

23) Take a look at Figure 17, it plots the bad loans ratio of public sector banks.

Figure 17:

Figure 17, basically plots the gross non-performing advances ratio or simply put. the bad loans ratio of public sector banks, over the years. Bad loans are essentially loans in which the repayment from a borrower has been due for 90 days or more. There has been a huge jump in bad loans of public sector banks over the last two years.

On October 7, the Reserve Bank of India imposed restrictions on the banking activities of Oriental Bank of Commerce (OBC). OBC was the seventh public sector bank on which restrictions have been placed. Now, one-third of public sector banks have restrictions in place. And all is well with the Indian economy?

24) Take a look at Table 1.

Table 1:

| Gross NPAs (in Rs Crore) | Gross Advances | Gross non-performing advances ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indian Overseas Bank | 35,098 | 1,40,459 | 24.99% |

| IDBI Ltd. | 44,753 | 1,90,826 | 23.45% |

| Central Bank of India | 27,251 | 1,39,399 | 19.55% |

| UCO Bank | 22,541 | 1,19,724 | 18.83% |

| Bank of Maharashtra | 17,189 | 95,515 | 18.00% |

| Dena Bank | 12,619 | 72,575 | 17.39% |

| United Bank of India | 10,952 | 66,139 | 16.56% |

| Oriental Bank of Commerce | 22,859 | 1,57,706 | 14.49% |

| Bank of India | 52,045 | 3,66,482 | 14.20% |

| Allahabad Bank | 20,688 | 1,50,753 | 13.72% |

| Punjab National Bank | 55,370 | 4,19,493 | 13.20% |

| Andhra Bank | 17,670 | 1,36,846 | 12.91% |

| Corporation Bank | 17,045 | 1,40,357 | 12.14% |

| Union Bank of India | 33,712 | 2,86,467 | 11.77% |

| Bank of Baroda | 42,719 | 3,83,259 | 11.15% |

| Punjab & Sind Bank | 6,298 | 58335 | 10.80% |

| Canara Bank | 34,202 | 3,42,009 | 10.00% |

Source: Author calculations on Indian Banks’ Association data.(The table does not include the associate banks of the State Bank of India which were merged into it).

What does Table 1 tell us? It tells us that many public sector banks are in a big mess on the bad loans front. Banks like Indian Overseas Bank and IDBI with bad loans ratio of 24.99 per cent and 23.45 per cent, will pull down the performance of any big bank they are merged with.

Even the big banks like Union Bank of India, Bank of Baroda, Punjab National Bank and Canara Bank, have a bad loans ratio of 10 per cent or more. If and when weaker banks are merged with these banks, their performance will only deteriorate. The question to ask is, why are many of these banks still being allowed to operate?

25) The capacity utilisation of 805 manufacturing companies tracked by the RBI OBICUS survey fell to 71.2 per cent during the period April to June 2017. This is the lowest in seven quarters.

I guess I will stop at this. There are many other economic indicators which can be used to point out that all is not well with the Indian economy. (For more details on how PM Modi cherry picked data to build a positive economic narrative, you can click here and here). Of course, this is not to say that there are no positive economic indicators right now. But the negative indicators far outnumber the positive ones.

As I keep saying, the first step towards solving a problem is recognising that it exists. But that doesn’t seem to be the case with PM Modi. In his world, all is well.

The column originally appeared on Equitymaster on October 9, 2017.