The prime minister Narendra Modi in a speech yesterday assured the nation that All is Well with the Indian economy, and that there was no reason to worry.

He offered data to sell his argument. Let’s go through some of the data that he offered and see what he told us and more importantly what he did not.

1) The fiscal deficit of the government has fallen from 4.5 per cent of the gross domestic product (GDP) in 2013-2014, when Manmohan Singh was prime minister, to 3.5 per cent in 2016-2017. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends.

Yes, the fiscal deficit has come down. A major reason for this is the fall in oil prices, since Modi took over as prime minister. On May 26, 2014, the day Modi was sworn in as prime minister, the price of Indian basket of crude had stood at $108.1 per barrel. As of October 4, 2017, the price was at $55 per barrel, having fallen to even lower levels during the period.

Oil prices go up and down due to a whole host of reasons and Modi’s government has almost no role to play in it.

The central government has captured much of this fall in price of oil, by increasing the excise duties on petrol and diesel, thereby increasing its earnings, and thereby bringing down the fiscal deficit. As they say, there is a difference between making things simple and making them simplistic.

2) Prime Minister Modi also claimed in his speech that the current account deficit has improved from -1.7 per cent of the GDP in 2013-2014 to -0.7 per cent of the GDP in 2016-2017. The current account deficit is the difference between total value of imports and the sum of the total value of its exports and net foreign remittances. Or to put it in simpler terms, it is the difference between outflow (through imports) and inflow (through exports and foreign remittances) of foreign exchange.

Again, this has primarily been account of fall in the price of oil and thus a fall in the total amount of dollars that India pays for importing oil. India imports around 80 per cent of the oil that it consumes. Hence, Modi’s government has had very little role to play in the fall of the current account deficit.

It further needs to be pointed out that imports are a negative entry in the GDP calculation. So, if imports fall, the GDP rises automatically, assuming everything else stays the same. Falling oil imports are a big reason for the pick-up in the GDP growth, during Modi’s tenure as prime minister.

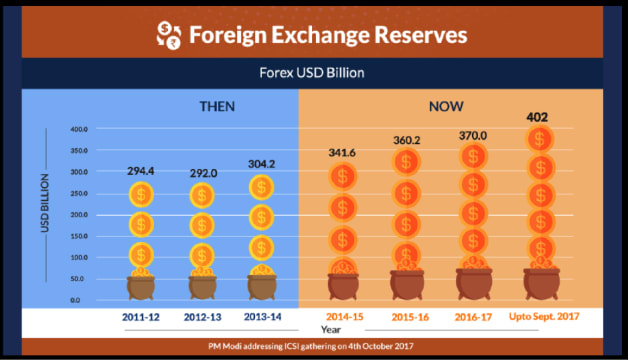

3) Take a look at the following chart, which was a part of the prime minister’s presentation yesterday.

Source: https://cdn.narendramodi.in/economy_1.pdf

As per this chart, the total foreign exchange reserves have risen by close to $ 60 billion during the period that Modi has been prime minister. In contrast, they were more or less flat when Manmohan Singh was the prime minister. At least that is what the above chart suggests.

This is primarily because of data has been taken from the end of 2011-2012 onwards. What happens if the data would have been taken from the end of 2003-2004 onwards. Manmohan Singh first became prime minister in May 2004.

As of March 31, 2004, the total foreign exchange reserves were at around $113 billion. By March 2014, they had jumped to around $304 billion. This meant an increase of 10.4 per cent per ear on an average. Between April 2014 and September 2017, the growth rate in foreign exchange reserves has been at 8.3 per cent per year on an average.

Hence, foreign exchange reserves accumulated at a much faster rate during Manmohan Singh’s tenure as prime minister. Of course, a bulk of these gains came during the first five years of the tenure, when the forex reserves increased at the rate of 17.4 per cent per year. Between 2009 and 2014, when the Congress led UPA made a mess of the economy, the increase in foreign exchange slowed down dramatically to 3.8 per cent per year on an average.

Basically, who did well, Singh or Modi, on the foreign exchange front, depends on where we start measuring from.

4) Prime Minister Modi further said that the interest rate that the government pays on the money that it borrows has fallen from 8.45 per cent in 2013-2014 to 7.16 per cent in 2016-2017. This has happened primarily due to two reasons. The falling fiscal deficit has led to the government having to borrow lesser in proportion to the size of the economy. With the government borrowing lesser, interest rates have come down.

It is important to remember here that the government has had to borrow lesser because it has increased excise duty on petrol and diesel and captured the bulk of the gain of falling oil prices.

Also, after demonetisation, a huge amount of deposits ended up with banks. These deposits were reinvested into government securities and in the process interest rates on government securities came down.

5) Prime Minister Modi pointed out that food inflation is in negative territory. The question is, is that a good thing? Why is food inflation in negative territory? It is in negative territory because farmers haven’t got the right prices for their produce. This is primarily on account of the fact that agri-supply chains have collapsed in the aftermath of demonetisation, forcing farmers to sell their produce at rock bottom prices.

The thing is there is no free lunch in economics. The collapse in food prices led to farmers demanding a waiving off agriculture loans and that has happened in state after state. It is ultimately expected to cost the nation, in the form of state governments compensating banks, more than Rs 2 lakh crore.

6) Over and above this, the prime minister shared data on a few consumption data points. Car sales, two-wheeler sales and tractor sales have improved, since June, hence, all is well.

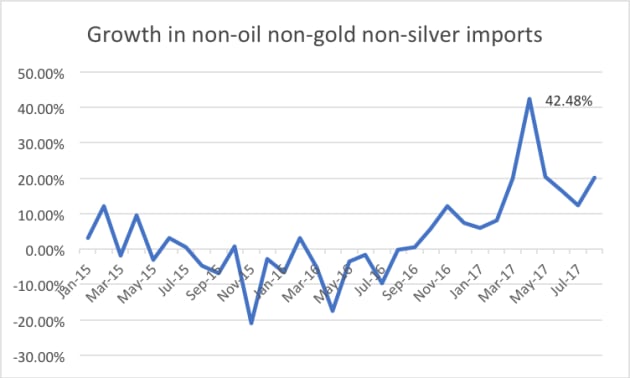

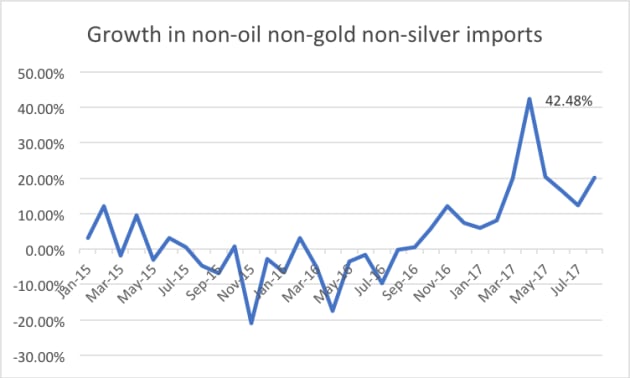

What the prime minister did not tell us is the rapid rise in non-oil non-gold non-silver imports, post demonetisation. Take a look at the following chart.

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry.

Imports also represent consumer demand at the end of the day, even though that demand does not add to the country’s GDP. For example, every time an Indian buys an electronic good manufactured in China, he is adding to the consumer demand but not to the GDP. Of course, he is adding to the Chinese GDP because exports are a positive entry into the GDP formula.

Hence, if we remove the imports of oil, gold and silver, from the total imports number (in dollars), what remains (i.e. non-oil non-gold non-silver imports) is a good indicator of consumer demand.

The above chart tells us that non-oil non-gold non-silver imports have grown at an extremely fast rate after October 2016. They are growing at rates at which they haven’t grown for a couple of years. What is happening here?

Demonetisation destroyed domestic supply chains. Without supply chains products can’t move. This has resulted in consumer demand being fulfilled through imports.

This is clearly visible in the huge growth of non-oil non-gold non-silver imports. What this also means is that as demonetisation destroyed supply chains in India, it also led to a huge job destruction. If goods weren’t moving, there was no point in producing them either. This meant shutdown of firms and massive job losses.

Further, by importing stuff that we used to produce in India earlier, we have helped the manufacturing business in foreign countries and in the process “possibly” helped create jobs there.

Of course, this is something that the prime minister did not tell us in his speech. What he further did not tell us is that:

a) During the course of this financial year between April and August 2017, the total outstanding loans of banks (non-food credit) have shrunk. Only retail loans are growing, loans to industry, agriculture and services have shrunk. This, even though interest rates have fallen. What this clearly tells us is that a large section of the economy is not in a good shape and in no mood to borrow money and that is not a good thing.

b) As on March 31, 2017, 22 out of 27 public sector banks had a bad loans ratio of 10 per cent or more. This basically means that out of every Rs 100 of loans given by these banks, Rs 10 or more of loans had gone bad and weren’t being repaid.

In fact, five banks had a bad loans rate more than 20 per cent, which basically means that more than one-fifth of the loans given by these banks had gone bad and were not being repaid.

This is a problem that has only grown during Modi’s tenure. He and his government have sat on it, and only blamed the previous government for the mess.

c) All the so-called attack on black money has had a very limited impact on the price of real estate. While prices haven’t risen, they haven’t fallen either. This essentially means that homes continue to remain unaffordable for most people.

d) There has been almost no talk on how demonetisation and now the badly implemented GST have played havoc with the functioning and the existence of small and medium enterprises. If small and medium enterprises keep getting destroyed how is the country ever going to create jobs. It is worth remembering here that one million Indians are entering the workforce every year. Where are the jobs for these people?

e) Our primary education system continues to remain in a mess, with most children finding it difficult to read, write and do basic maths. It has been more than 40 months since Modi was elected prime minister, and nothing serious has been done on this front.

f) The non-government GDP has collapsed to 4.3 per cent. The non-government part of the GDP amounts to close to 90 per cent of the economy.

g) The growth rate of industry in general and manufacturing and construction in particular is at a five-year low. The manufacturing part of industry grew at 1.17 per cent during April to June 2017, whereas construction grew by 2 per cent during the same period. Also, it is worth pointing out here that manufacturing and construction together form 82-85 per cent of industry. If these sectors are barely growing, how will any jobs be created?

I can go and on the bad state of the Indian economy, but there is only so much time and only so much space. The trouble with trying to be clever all the time is that ultimately you get found out and more importantly, the nation doesn’t go anywhere.

The first step towards solving a problem is recognising that it exists. The economy has a problem, it is time that the government acknowledged that and worked towards it.

The column originally appeared on Huffington Post on October 5, 2017.