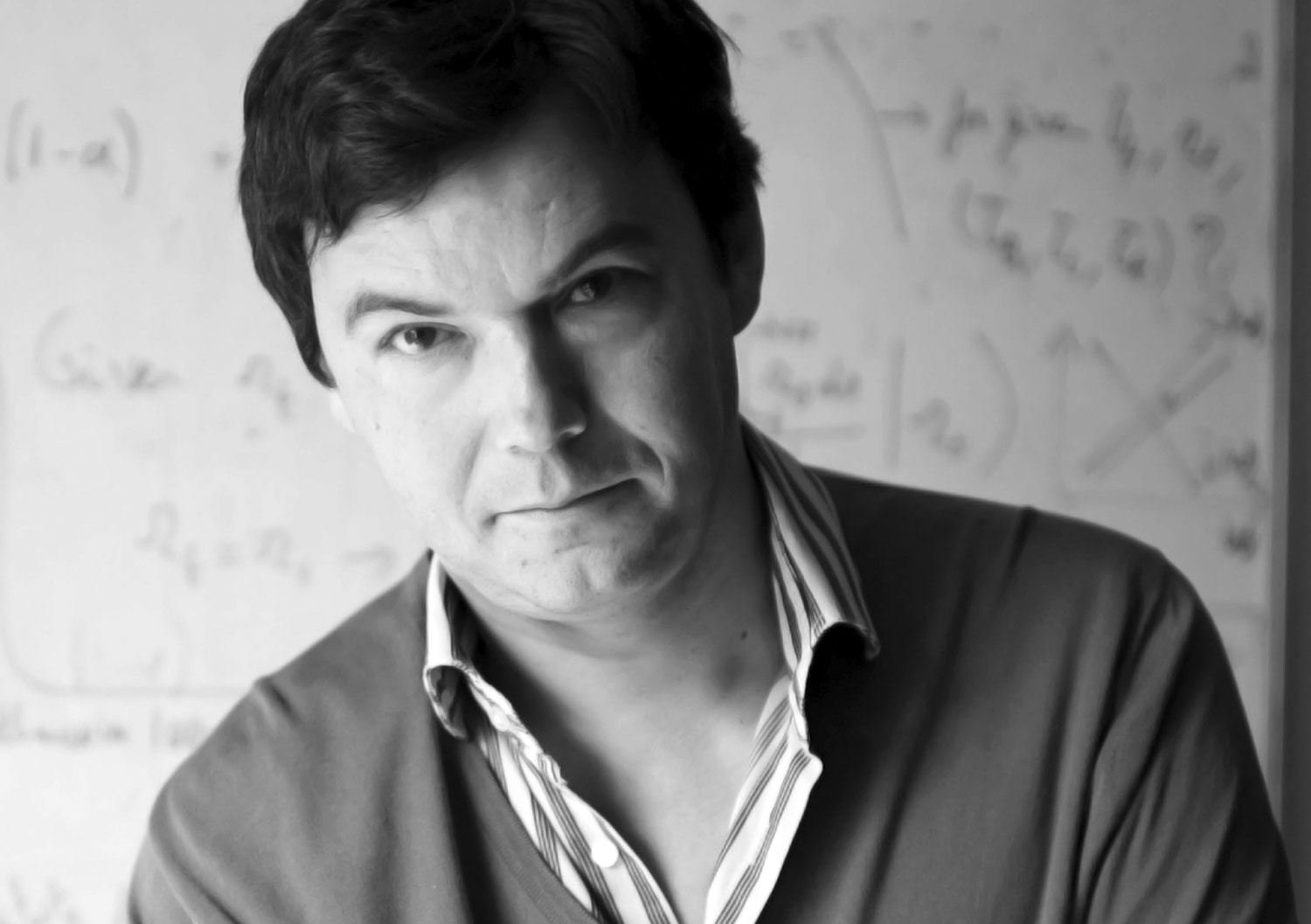

The French economist Thomas Piketty whose bestselling book Capital in the Twenty First Century was published last year, in an interview to the German newspaper Die Zeit recently said: “What struck me while I was writing is that Germany is really the single best example of a country that, throughout its history, has never repaid its external debt. Neither after the First nor the Second World War.”

In the recent past, Germany has been insistent that Greece repay the money that it owes to the economic troika of the European Central Bank, the European Commission and the International Monetary Fund. As Piketty remarked: “When I hear the Germans say that they maintain a very moral stance about debt and strongly believe that debts must be repaid, then I think: what a huge joke! Germany is the country that has never repaid its debts. It has no standing to lecture other nations.”

In order to understand what Piketty meant we will have to go back nearly 100 years. At the end of the First World War in 1918, Germany had to compensate the victorious Allies (read Britain, France, and America primarily) for the losses it had inflicted on them.

At the reparations commission, the British delegation wanted Germany to pay $55 billion as compensation to the Allies. This was a huge number, given that the German gross domestic product (GDP) at that point of time stood at around $12 billion.

The Americans were fine with anything in the range of $10 to $12 billion and did not want anything more than $24 billion. The French did not put out a number of what they were expecting but they wanted a large reparation from Germany.

This was primarily because when the French had been in a similar situation in 1870 they had paid up Germany. After France had lost the Franco-Prussian War, Germany had asked France to pay 5 billion francs to make good the losses that it had faced during the course of the war. The French had rallied together and paid this money in a period of just two years.

Given this historical background, they saw no reason why Germany should not be made to pay for the losses that France had suffered. The French assumed that like they had paid the Germans 50 years back, the Germans would also pay up. As Piketty put it in the interview: “However, it has frequently made other nations pay up, such as after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, when it demanded massive reparations from France and indeed received them.”

In May 1919, it was decided that Germany would pay the Allies an initial amount of $5 billion by May 1, 1921. The final reparation amount to be paid would be decided by a new Reparations Commission.

Finally, the total reparations amount that Germany would have to pay the allies was set at $12.5 billion, which was equal to the pre-war GDP of Germany. To repay this amount, Germany would have had to pay around $600–$800 million every year.

Germany was in a bad state financially and at the end of the war had a budget deficit that ran into 11,300 million marks (the German currency at that point of time). As the government did not earn enough revenue to meet its expenditure due to the high-reparation payments, it started to print money to finance pretty much everything else.

This finally led to the German hyperinflation of 1923. Inflation in Germany at its peak touched a 1,000 million percent. Interestingly, one view prevalent among economic historians is that Germany engineered this hyperinflation to ensure that it did not have to pay the reparation amounts. The hope was that, with inflation at such high levels, the Allied countries would deal with Germany sympathetically when it came to deciding on reparation payments. And this is precisely what happened.

By the time the hyperinflation came to an end, the economy was in such a big mess that the reparation payments had slowed down to a trickle. And it so turned out that over the next few years more was paid to Germany in the form of various loans than it paid the Allies in reparations. After this, Germany regularly continued to default on the payments and finally when Hitler came to power in 1933, he stopped these payments totally.

As mentioned earlier, after the hyperinflation of 1923, money had started to pour in from other nations into Germany. A substantial part of the preparation for the Second World War was financed through this money.

The Second World War started in 1939 and ended in 1945. Given the fact that Hitler had used foreign money to get the Second World War started, the directive at the end of the Second World was that nothing should be done to restore the German economy above the minimum level required to ensure that there was no disease or unrest, which might endanger the lives of the occupying forces.

Eventually, the realization set in that an economic recovery in Europe was not possible without an economic recovery in Germany, the largest economy in Europe. The American Secretary of State, George C. Marshall, after having returned from Moscow in April 1947, was convinced that Europe was in a bad shape and needed help. This eventually led to the Marshall Plan. From 1948 to 1954, the United States gave $17 billion to 16 countries in Western Europe, including Germany, as a part of the Marshall Plan.

So what does all this history tell us? One is that Germany did not repay the debt that it owed to the Allied nations and hence, as Piketty said: “Germany is the country that has never repaid its debts. It has no standing to lecture other nations.”

But there is a bigger lesson here—that demanding austerity from Greece in order to be able to repay the debt isn’t exactly the answer. The German experience after the First World War precisely proves that.

The Nobel Prize winning economist Amartya Sen, writes about the German experience after the First World War, in a recent column. As he writes: “Germany had lost the battle already, and the treaty was about what the defeated enemy would be required to do, including what it should have to pay to the victors. The terms…as Keynes saw it…included the imposition of an unrealistically huge burden of reparation on Germany – a task that Germany could not carry out without ruining its economy.”

And this is precisely what has happened in Greece over the last few years. The country now owes close to 240 billion euros to the economic troika. The austerity measures have had a highly negative impact on the Greek economy. As Nobel Prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz recently wrote: “Of course, the economics behind the programme that the “troika” foisted on Greece five years ago has been abysmal resulting in a 25% decline in the country’s GDP. I can think of no depression, ever, that has been so deliberate and had such catastrophic consequences: Greece’s rate of youth unemployment, for example, now exceeds 60%.”

This has essentially led to a situation where the total amount of debt with respect to the Greek gross domestic product (GDP) went up instead of going down. Currently the total debt to GDP ratio of Greece stands at a whopping 175%. And this number is likely to go up further in the days to come. In comparison the number was at 129% in 2009.

The only way Greece can perhaps be able to repay some of its external debt is if economic growth comes back. And that is not going to happen through more austerity. As Sen puts it: “Keynes ushered in the basic understanding that demand is important as a determinant of economic activity, and that expanding rather than cutting public expenditure may do a much better job of expanding employment and activity in an economy with unused capacity and idle labour. Austerity could do little, since a reduction of public expenditure adds to the inadequacy of private incomes and market demands, thereby tending to put even more people out of work.”

As economic history has shown more than once, whenever people in decision making positions forget what Keynes said, the world usually ends up in a bigger mess.

The article originally appeared on Firstpost on July 7, 2015

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)