Vivek Kaul and R Jagannathan

The Sahara group sure has a way with numbers. A separate number for separate occasions.

On 1 December this year, an advertisement issued by the group said two of its companies — Sahara India Real Estate Corporation (SIREC) and Sahara Housing Investment Corporation (SHIC), which fell foul of Sebi – had returned Rs 33,000 crore of money collected through optionally full convertible debentures (OFCDs).

The ad read: “We started OFCD in these two companies in 2008/2009. Most of the money deposited with us was for 5 to 10 years. But now we have cleared around Rs 33,000 crores liability.”

On 5 December, a Supreme Court bench headed by Chief Justice of India Altamas Kabirextended the deadline for repayment till February. It ordered Sahara to pay Rs 5,120 crore immediately to Sebi, Rs 10,000 crore by January, and the rest by February. This suggests that the court still thinks nearly Rs 25,000 crore may be owed to investors.

A Sahara ad released on 9 December claimed it owed investors only Rs 2,620 crore as on date. It mentions that “Total liability was around Rs 25,000 crores of both the OFCD companies” (Note: since there are no dates, nothing can be verified), but then says only Rs 2,620 crore of this Rs 25,000 crore was left unpaid, for which it had given Sebi a cheque – adding an extra Rs 2,500 crore in case there were any discrepancies.

Sahara has a lot of explaining to do. The group, whose attitude has been described as “shaky” by the Supreme Court, is not telling us the real story.

The Supreme Court judgment of 31 August 2012 takes note of an outstanding of Rs 24,029.73 crore as on 31 August 2011 between the two companies that was owed to 29.61 million OFCD investors. (Read the full judgment here)

One wonders at what point did Sahara managed to pay investors Rs 33,000 crore when the figure was only around Rs 24,029 crore in August 2011?

The only way the group could have repaid Rs 33,000 crore over the lifecycle of the OFCD investment was if there was a huge churn even in the initial years of the scheme in 2008-11. Sebi banned them from continuing the scheme in June 2011.

Sahara offered investors three types of bonds through SIREC – the Abode 10-year bond, where early redemptions were possible only after five years; the Real Estate bonds of five years, where no early redemptions were possible; and the Nirmaan four-year bond, where redemptions were possible after 18 months.

The bulk of the investors opted for the first two bonds – Abode and Real Estate, where no redemptions were possible for five years. Since the SIREC OFCDs were issued only from 2008 (SHIC began only towards end-2009), how is it possible that such a large bulk of OFCDs were refunded to investors when they were not due?

As Firstpost noted earlier, a majority of SIREC’s investors (13.036 million) preferred to invest in Real Estate bonds worth Rs 7,120 crore. And Abode bonds came in for second preference, as 7.06 million invested in them, but the amount invested was larger at Rs 8,411 crore. Nirmaan bonds had a small following of 13.06 lakh investors with an investment of Rs 1,959 crore.

The big question is this: how can Sahara claim that it repaid nine-tenths of the money collected (only Rs 2,620 crore left out of Rs 25,000 crore or more) when the two biggest OFCDs issued by SIREC did not have any clause for premature encashment before five years – which meant only in 2013 and not earlier?

There was, of course, a provision for premature refunds in case of deaths, but Sahara is not claiming that most of its investors had passed away during the term of the OFCDs.

The refund patterns disclosed in the Supreme Court’s judgment tell their own story.

Of the total amount of Rs 19,400.87 crore collected by SIREC till 13 April 2011, only 11.78 lakh investors out of 23.3 million had cashed out with Rs 1,744.34 crore by 31 August 2011 – leaving a balance of Rs 17,656.53 crore.

In the case of SHIC, premature redemptions were a meagre Rs 7.3 crore (involving just 5,306 investors) out of total collections of Rs 6,380.50 crore – leaving a balance of Rs 6,373.20 crore.

These numbers are a part of the disclosures made by Sahara to the Securities Appellate Tribunal, which heard and threw out its appeal against Sebi, as on 31 August 2011, and remained part of the Supreme Court order a year later.

The questions are clear:

Why did Sahara not tell the Supreme Court what it owed investors during the hearings on the case? How come the Rs 2,620 crore figure came up only when the Supreme Court ordered it to pay Rs 24,029 crore?

How did Sahara manage to refund most of the money when the bulk of the bonds were not meant to be prematurely redeemed till 2013? How did dues of Rs 24,029 crore become Rs 2,160 crore, or even Rs 5,120 crore?

Did Sahara really refund the money or shift it to different schemes? Or why else would Sebi issue ads warning investors to avoid Sahara approaches? Business Standard clearly reports that investors under pressure are moving their money.

The newspaper reported that agents of the Sahara group were being pushed to collect sehmat patras (consent letters) from investors to show that their money had already been returned to them. “Agents, estimated to be a million strong, who sold OFCDs, often termed housing bonds, have been ordered to collect these letters, failing which their commissions are being stopped. With these consent letters, many of which are pre-dated, with dates ranging from as early as April to show that refunds were spread over a long period, documents such as account statements and passbooks in the hands of the customers are being collected,” the newspaper reported.

Also, money was being transferred to the new Q Shop venture launched by the group. The newspaper adds: “While this documentation process has been on, a significant portion of the money deposited in the accounts have already been transferred to the Q-Shop plan, another money raising plan being marketed as a retail venture.”

What is interesting nonetheless is that the December 1 advertisement of Sahara makes a slightly different point. “Surprisingly in the Hindi belt particularly, we find the name of hundred of different persons, even the area names, including Village, Mohalla, Towns, Cities match. Most surprisingly many many fathers/husbands names also match, so it is very difficult to authentically ascertain the pattern of reinvestment, but through verbal conversations and also through computer data matching we try to understand the pattern. There is always persuasion by field workers out of their good relation with investors for reinvestment. We have vaguely observed that a good percentage of depositors/investors do not come back and go away with 100% of maturity/redemption amount. Another good percentage keep back their principal investment amount but they accept field workers request and reinvest the amount of earning with the company and a big percentage reinvest the full amount”.

How different is good percentage from a big percentage? Why can’t the company put out some real data especially when the advertisement goes onto to claim with utmost confidence that “if you go through the figures, you shall see a similar behaviour in all other institutions where commission is paid like Post Office, LIC etc.”

If Sahara can be so confident about the money going into Post Office investment schemes, and premium being paid towards Life Insurance Corporation of India’s insurance plans, then it can surely give us a little more detail about the money that it raises.

Sahara has a lot of explaining to do. The group, whose attitude has been described as “shaky” by the Supreme Court, is not telling us the real story.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on December 10, 2012.

Supreme Court

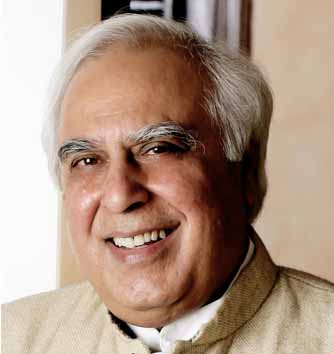

Sibal jumped the gun: SC may well see Coalgate as a scam

Vivek Kaul

Gyan Chaturvedi, a famous Hindi writer of this era, makes a very interesting point in the introduction to his 2004 book Marichika . He writes “jungle ke apne niyam hote hain aur wahan kissi tark ka koi sthan nahi hota (a jungle has its own rules and there is no space for any reasonable arguments to be made there).”

Nobody understands this much better than politicians operating in the jungle of politics. They rush to save their own skin and keep justifying what they had said earlier, despite evidence to the contrary. “My position is right because I had said so in the past,” is the logic with which they operate. There is no scope for a “reasonable argument” there.

The Telecom Minister Kapil Sibal’s reaction to the Supreme Court’s “opinions” on the government reference to it asking for broad-sweep clarifications on its policy of allocating natural resources is a very good example of the same. “We welcome the Supreme Court(SC) opinion. SC has confirmed what the government has been saying,” Sibal said yesterday.

This comment came after a five judge bench of the Supreme Court answered the questions it had been asked by the government of India through a Presidential reference on April 12,2012. Among other things the government had asked the Supreme Court to clarify on “whether the only permissible method for disposal of all natural resources across all sectors and in all circumstances is by the conduct of auctions.”

This question had arisen in light of the Supreme Court judgement cancelling the licenses given to 122 telecom companies in 2008, when A Raja was the Telecom Minister. The government had given out these licenses on the basis of “first come first serve” principle rather than auctioning them as they had done in the past and thus causing a huge loss to the exchequer.

In response to the government’s question the Supreme Court clarified “Auctions may be the best way of maximising revenue but revenue maximisation may not always be the best way to subserve public good. Common good is the sole guiding factor under Article 39(b) for distribution of natural resources. It is the touchstone of testing whether any policy subserves the “common good” and, if it does, irrespective of the means adopted, it is clearly in accordance with the principle enshrined in Article 39(b).”

This paragraph in the suggestions made by the Supreme Court perhaps got the politician in Sibal gloating and into the “I had told you so” mould. The government has maintained that auctioning natural resources is not always the best possible way to operate because it tends to drive up prices. For example, if coal is auctioned to the highest bidder, then power prices will go up. Hence, in lieu of the “common good” natural resources cannot always be sold to the highest bidder.

Let’s see how strong this argument holds in case of the coalgate scam. Between 1993 and 2011, the government gave away 195 coal blocks with total geological reserves of 44802.8million tonnes free to private and government companies. An estimate of the total amount of coal present in a block is referred to as geological reserve. Due to various reasons including those of safety, the entire reserve cannot be mined. The portion that can be mined is referred to as extractable reserve.

Of these 115 blocks were given to companies which would use coal that they produced from these captive blocks for the manufacture of cement and iron and steel, conversion of coal to oil and commercial mining. These blocks have geological reserves amounting to 20526.9 million tonnes of coal.

The manufacture of cement and iron and steel or commercial mining operations are “for profit” operations and cannot be termed as “common good”. Hence there was no reason for the government to give away these coal blocks for free. That is a clear interpretation that one can draw out of what the Supreme Court said.

Eighty coal blocks were given to companies for the manufacture of power. Of these 80 coal blocks, 53 blocks were given to companies for captive dispensation of power. These blocks had 10621.4 million tonnes of geological reserves of coal.

What this meant was that companies had to use the coal produced from the blocks they had been given to produce power to meet their internal needs. Hence a company manufacturing steel could use coal produce from its blocks to manufacture power needed to produce steel. The “free” coal blocks would allow them to produce power cheaply and thus bring down their costs and thus make higher profits from what they would have made. Again, the end result is a “for profit” operation and this cannot be categorized as “common good”.

Hence, 168 out of the 195 coal blocks with geological reserves of 31148.3 million tonnes were allocated to companies supposedly in “for profit” operations. The remaining 27 blocks with geological reserves of 13654.5 million tonnes were allocated for production of power. Of these seven blocks had been allocated to ultra mega power projects. The companies which were given these blocks could produce power cheaply because they did not have to pay for the coal block. This can be categorized as a “common good”.

Hence, common good is limited to around 30% of the coal reserves allocated under the government’s policy of giving away coal blocks for free. Even this can be questioned given that all the seven coal blocks (with geological reserves of 2607million tonnes) allocated to the ultra mega power projects are in the private sector. And no private sector company is in business to make a loss.

If Sibal had read the suggestions of the Supreme Court carefully enough he would have realised that Justice Jagdish Singh Khehar, one of the judges on the bench, does make the points I just raised above. “When natural resources are made available by the state to private persons for commercial exploitation exclusively for their individual gains, the state’s endeavour must be towards maximisation of revenue returns. This alone would ensure, that the fundamental right enshrined in Article 14 of the Constitution of India (assuring equality before the law and equal protection of the laws), and the directive principle contained in Article 39(b) of the Constitution of India (that material resources of the community are so distributed as best to subserve the common good), have been extended to the citizens of the country,”Kehar points out.

Given this, it clearly means that 70% of the coal blocks given away for free should have been auctioned because there is clearly no “common good” involved there.

Judge Kehar also pointed out that “No part of the natural resource can be dissipated as a matter of largesse, charity, donation or endowment, for private exploitation. Each bit of natural resource expended must bring back a reciprocal consideration. The consideration may be in the nature of earning revenue or may be to “best subserve the common good”. It may well be the amalgam of the two. There cannot be a dissipation of material resources free of cost or at a consideration lower than their actual worth. One set of citizens cannot prosper at the cost of another set of citizens, for that would not be fair or reasonable.”

Khehar also clearly points out that even though the Supreme Court was saying that the auction of natural resources wasn’t the right way to proceed always, but that did not mean that there should be no auctions at all. “Government should remain alive to the fact that disposal of some natural resources have to be made only by auction…A rightful choice, would assure maximization of revenue returns. The term “auction” may therefore be read as a means to maximize revenue returns,” the Judge said.

The Judge also makes it clear that in several situations giving away coal blocks for free wouldn’t work. “If the bidding process to determine the lowest tariff (of power) has been held, and the said bidding process has taken place without the knowledge that a coal mining lease would be allotted to the successful bidder, yet the successful bidder is awarded a coal mining lease. Would such a grant be valid?… Grant of a mining lease for coal in this situation would therefore be a windfall, without any nexus to the object sought to be achieved,” he said. Thus a power company which is in the business of selling power at commercial rates could get an undue benefit because it had access to free coal blocks.

Another interesting point that the Judge makes is that the man on the street should know why the decision has been taken in favour of a particular party. What this means in terms of the coalgate scam is that the government owes an explanation to the nation as to why relatives of ministers in the government got coal blocks for free? It also needs to tell us is how did dubious companies with no previous experience in any business land up with coal blocks?

Kapil Sibal clearly jumped the gun while making the comments that he did yesterday. Guess by now he would have found time to read through what the Supreme Court had to say in totality. Given this he would understand that the underlying tone of the suggestions made by the Supreme Court is that the UPA government screwed up majorly while giving away coal blocks for free since they came to power in 2004.

(The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on September 28,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/business/sibal-jumped-the-gun-sc-may-well-see-coalgate-as-a-scam-471881.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

Why the poor are willing to hand over their money to Sahara

Vivek Kaul

Abhijit V Banerjee and Esther Duflo in their book Poor Economics – Rethinking Poverty & the Ways to End It write a very interesting story about a woman they met in the slums of Hyderabad. This woman had borrowed Rs 10,000 from Spandana, a microfinance institution.

As they write “A woman we met in a slum in Hyderabad told us that she had borrowed 10,000 rupees from Spandana and immediately deposited the proceeds of the loan in a savings bank account. Thus, she was paying a 24 percent annual interest rate to Spandana, while earning about 4 percent on her savings account”.

The question of course was why would anyone in their right mind do something like this? Borrow at 24% and invest at 4%? But as the authors found out there was a clear method in the woman’s madness. “When we asked her why this made sense, she explained that her daughter, now sixteen, would need to get married in about two years. That 10,000 rupees was the beginning of her dowry. When we asked why she had not opted to simply put the money she was paying to Spandana for the loan into her savings bank account directly every week, she explained that it was simply not possible: other things would keep coming up…The point as we eventually figured out, is that the obligation to pay what you owe to Spandana – which is well enforced – imposes a discipline that the borrowers might not manage on their own.”

The example brings out a basic point that those with low income find it very difficult to save money and in some cases they even go to the extent of taking a loan and repaying it, rather than saving regularly to build a corpus.

This includes a lot of very small entrepreneurs and people who do odd jobs and make money on a daily basis. Such individuals have to meet their expenses on a daily basis and that leaves very little money to save at the end of the day. Also the chances of the little money they save, being spent are very high. As Abhijit Banerjee told me in an interview I did for the Economic Times “The broader issue is that savings is a huge problem. Cash doesn’t stay. Money in the pillow doesn’t work.”

Hence, as the above example showed it is easier for people to build a savings nest by borrowing and then repaying that loan, rather than by saving regularly.

Another way building a savings nest is by visiting a bank regularly and depositing that money almost on a daily basis. But that is easier said than done. In a number of cases, the small entrepreneur or the person doing odd jobs, figures out what he has made for the day, only by late evening. By the time the banks have closed for the day.

The money saved can easily be spent between the evening and the next morning when the banks open. Also, in the morning the person will have to get back to whatever he does, and may not find time to visit the bank. Banks also do not encourage people depositing small amounts on a daily basis. It pushes up their cost of transacting business.

But what if the bank or a financial institution comes to the person everyday late in the evening, once he is done with his business for the day and knows exactly what he has saved for the day. It also does not throw tantrums about taking on very low amounts.

This is precisely what Subrata Roy’s Sahara group has been doing for years, through its parabankers who number anywhere from six lakh to a million. They go and collect money from homes or work places of people almost on a daily basis.

The Sahara group fulfilled this basic financial need of having to save on a daily basis for those at the bottom of the pyramid (as the management guru CK Prahalad called them). The trouble of course was that there was very little transparency in where this money went. The group has had multiple interests ranging from real estate, films, television, and now even retail. A lot of these businesses are supposedly not doing well.

Over the last few years, both the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and Securities and Exchange Board of India(Sebi), have cracked down on the money raising schemes of the Sahara group. In a decision today, the Supreme Court of India has directed that the Sahara group refund more around Rs 17,700 crore that it raised through its two unlisted companies between 2008 and 2011. The money was raised from 2.2crore small investors through an instrument known as fully convertible debenture. The money has to be returned in three months.

Sebi had ordered Sahara last year to refund this money with 15% interest. This was because the fund-raising process did not comply with the Sebi rules. Sahara had challenged this, but the Supreme Court upheld Sebi’

The question that arises here is that why has Sahara managed to raise money running into thousands of crores over the last few decades? The answer probably lies in our underdeveloped banking system. In a November 2011 presentation made by the India Brand Equity Foundation ( a trust established by the Ministry of Commerce with the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) as its associate) throws up some very interesting facts. A few of them are listed below:

– Despite healthy growth over the past few years, the Indian banking sector is relatively underpenetrated.

– Limited banking penetration in India is also evident from low branch per 100,000 adults ratio – – Branch per 100,000 adults ratio in India stands at 747 compared to 1,065 for Brazil and 2,063 for Malaysia

– Of the 600,000 village habitations in India only 5 per cent have a commercial bank branch

– Only 40 per cent of the adult population has bank accounts

What these facts tell us very clearly is that even if a person wants to save it is not very easy for him to save because chances are he does not have a bank account or there is no bank in the vicinity. This is where Sahara comes in. The parabanker comes to the individual on a regular basis and collects his money.

As a Reuters story on Sahara points out “Investors in Sahara’s financial products tend to be from small towns and rural areas where banking penetration is low. “They see Sahara on television everyday as sponsor of the cricket team and that leads them to believe that this is the best company,” said a spokesman for the Investors and Consumers Guidance Cell, a consumer activist group.”

Sahara has built trust over the years by being a highly visible brand. It sponsors the Indian cricket and hockey team. It has television channels and a newspaper as well. Hence people feel safe handing over their money to Sahara.

The irony of this of course is that RBI which has been trying to shut down the money raising activities of Sahara is in a way responsible for its rise, given the low level of banking penetration in the country.

(The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 31,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/business/why-the-poor-are-willing-to-hand-over-their-money-to-sahara-438276.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])