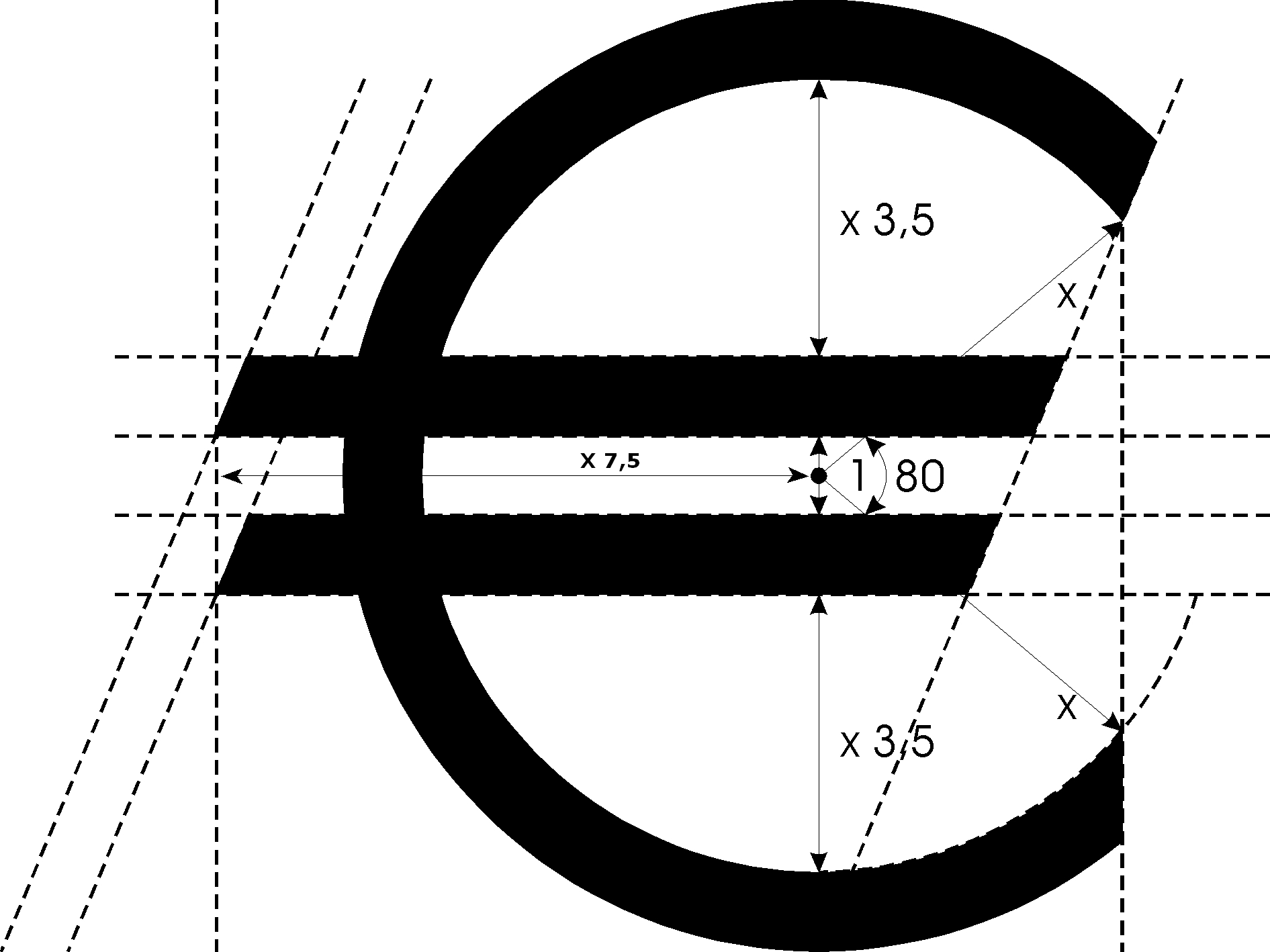

“The Greeks invented democracy and, let’s not forget, tragedy,” writes Chris Allbritton in The Daily Beast. And the fact that the country invented democracy had a very important role to play in it being accepted into the Eurozone in the first place. Eurozone is essentially a term used in order to refer to the countries using the euro as their currency.

As Neil Irwin writes in The Alchemist—Inside the Secret World of Central Bankers: “Greece…was where democracy was invented, the birthplace of the European idea, the original European empire.” But all that was in the past.

Greece voted an overwhelming 61.3% no in the referendum held yesterday, to decide on the following question:

““Should the proposal that was submitted by the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund at the Eurogroup of 25 June 2015, which consists of two parts that together constitute their comprehensive proposal, be accepted? The first document is titled ‘Reforms for the completion of the Current Programme and beyond’ and the second ‘Preliminary Debt Sustainability Analysis.’’”

The referendum essentially asked Greeks to decide whether they were ready to suffer from more austerity measures, like the government cutting back on pensions, raising taxes etc., so that the it could be bailed out again by the economic troika of the European Central Bank, the European Commission and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

To this, the Greeks have voted an emphatic no. The question is what happens next? Will this democratic decision of the Greeks turn out to be a tragic one in the days to come? ““Greece has just signed its own suicide note” – Mujitba Rahman, head of European analysis at the Eurasia Group risk consultancy, told the Financial Times.

But the reality of the situation is not as unidimensional as that. Allow me to explain.

The Greek banks are running out of money. As former US treasury secretary Lawrence Summers wrote on his blog: “The referendum is probably the second most important event of the week in Greece. However it turns out, Greek banks will run out of cash early in the week, probably on Monday [i.e. today].”

Currently, the Greek banks are shut. Cash withdrawals from ATMs are limited to 60 euros a day and are likely to be cut further. This can’t be a good scenario for ordinary Greek citizens. Further, it would be stupid to think that those who voted ‘no’ would have not realised that voting ‘no’ would mean trouble ahead. So to that extent people are ready to bear some amount of economic pain.

Also, an economy cannot function without currency. In fact, fearing precisely this scenario, the Greeks have been stocking up on food. As The Globe and Mail reports: “Already, some basic items such as medicines were running low as cash supplies ran short and payment systems ceased to exist. Many Greeks have been loading up on food staples for fear that supermarkets will be unable to buy products.”

The Greek government employees need to be paid on July 12. How will that payment be made? Governments in the past have resorted to issuing IOUs or scrips. The Greece government could do the same as well. The problem here is that the confidence in scrips issued by a bankrupt government wouldn’t be very high.

The Greek politicians believe that with a ‘no’ vote they are in a better negotiating position with the economic troika and other leaders in Europe. As Panos Skourletis, the Greek labour minister said: “The government can go now with a very strong card to continue negotiations [with creditors].”

The reason for this is very straight forward—with a ‘no’ vote the fear that Greece will exit the euro is even higher. And this is something that will strike at the very heart of the euro, given that it is ultimately a political idea, which hopes to bring the entire region closer through economic integration, with the hope of preventing any future wars in the years to come.

One of the first things that is likely to happen if Greece exits is that the country will redominate all its debt in its new currency, which is likely to be the drachma. Also this will set a precedence for other countries like Spain, Portugal and Italy. And this can’t be good for the entire idea of euro.

Further, though no German politician will publicly admit to it, but the euro has tremendously helped increase the German exports. In 1995, German exports made up for 22% of the gross domestic product (GDP). By 1999, this number had run up to 27.1%. In 2004, five years after the euro came into being, the German exports to GDP ratio stood at 35.5%. In 2008, the number reached 43.5%. As the impact of the financial crisis started to spread around the number fell to 37.8% in 2009. Nevertheless, the German exports to GDP ratio has recovered since then and in 2014 stood at 45.6%.

With the euro becoming the common currency across most of Europe, the exchange rate risk that businesses had to face while exporting goods and services was taken out of the equation totally. This has benefitted Germany the most, given the productivity of its business.

And will Germans want to get rid of this advantage by chucking out the Greeks and start a process which questions the entire idea of euro? As Niels Jensen writes in the Absolute Return Letter for July 2015 titled A Return to the Fundamentals? : “Germany…actually benefit[s] from the damage that Greece has done to the value of the euro. Poor domestic demand as a result of challenging demographics have made exports the most likely way to secure decent economic growth, and a relatively weak euro has been tremendously helpful in that respect. Imagine how much stronger the euro would have been if every member country had the fiscal discipline of Germany!”

The public posture maintained by the German leaders has been very aggressive. As Sigmar Gabriel, the deputy chancellor of Germany said: “With the rejection of the rules of the euro zone… negotiations about a programme worth billions are barely conceivable.”

There are a spate of meetings scheduled between European leaders today and tomorrow. And this is where some hard decisions will have to be made. If the politicians continue to believe in the idea of euro and the Eurozone, then they will have to treat Greece with kid gloves and not push for more austerity.

On July 20, 2015, Greece has to make a payment of 3.5 billion euros to the European Central Bank for a bond that is maturing. I guess things would have become much clearer in the Eurozone and Greece by then.

So, watch this space.

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

The column originally appeared on Firstpost on July 6, 2015