When the production of any commodity goes up, its price falls.

That’s Economics 101.

But economics is not physics. And what sounds true, may not be true at all.

Take the case of the report in The Times of India edition dated May 12, 2013 which points out “US agricultural department and…the Food and Agriculture Organisation(FAO) have predicted record global output of cereals…raising hopes of snapping the trend of worryingly rising food prices.”

The US department of agriculture expects the global production of wheat to rise by 6.9% to 701 million tonnes in 2013-2014 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2013 and March 31, 2014) from the previous year. The production of rice is expected to rise by 1.9% to 479 million tonnes.

This rise in production The Times of India feels will bring down cereal prices in particular and food prices in general. The cereal inflation was 4.62% in March 2012. But it had shot up to 18.36% in March 2013.

Will this inflation come down? Another reason in favour of increased production is the fact that the India Meteorological Department has said that the South West Monsoon will be normal this year. The South West Monsoon is very important for the production of rice given that half of India’s area under cultivation is still at the mercy of monsoons. Irrigation wherever its available is also dependent on rainfall.

While increase in production of a commodity does have an impact on its price, but there are other bigger factors at play in the Indian case. Every year the government of India sets a minimum support price for rice and wheat. At this price, it buys rice and wheat from farmers, through the Food Corporation of India(FCI) and other state government agencies.

This price is declared in advance in order to give the farmer an idea of what he is likely to get for his produce. While the idea behind MSP is noble but it has essentially become a tool of give-aways in the hands of politicians. The MSPs for both wheat and rice have been raised dramatically over the last few years.

In 2009-2010 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2009 and March 31, 2010), the MSP for rice paddy was Rs 1000 per quintal (i.e. 100 kilograms). This was increased to Rs 1250 per quintal in 2012-2013. For wheat this went up from Rs 1080 per quintal to Rs 1350 per quintal.

So MSPs have gone up dramatically over the last few years. This has resulted in more and more rice and wheat being produced and landing up with the FCI and other agencies which operate on its behalf. The way the current system works is that FCI is obligated to buy all the rice or wheat that the farmer wants to sell as long as a certain quality standard is met. This has led to a situation where farmers find it favourable to produce rice and wheat because they have a ready buyer for all their produce, at a price they know in advance.

Hence the stocks with the stock of rice and wheat with the government has gone up dramatically. At the beginning of March 1, 2013, the total rice and wheat stock stood at 62.8 million tonnes. Now compare this with the minimum buffer of 25 million tonnes that needs to be maintained. So the government is buying much more rice and wheat than it actually needs to maintain a buffer and distribute through its various social security programmes. As an article in the May 26, 2013, edition of Business Today points out “A few years of high minimum support price (MSP) – floor price at which government buys all the wheat and rice offered by farmers – has led to the massive procurements. This, however, has not been followed through with regular releases into the market.” So the prices of rice and wheat has gone up, as more of it lands up in the godowns of FCI and not in the open market. Or as Madan Sabnavis, Chief Economist at credit rating agency Credit Analysis & Research Ltd told Business Today “Excess procurement is leading to an artificial scarcity.”

This is something even the government agrees with. A December 2012, report brought out by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices, which comes under the Ministry of Agriculture points out “Since 2006-07, the procurement levels for rice and wheat have increased manifold…Currently, piling stocks of wheat with FCI has led to an artificial shortage of wheat in the market in the face of a bumper crop. Wheat prices have gone up in domestic markets by almost 20 percent in the last three months alone (in the three months upto December 2012, when the CACP report was released), because of these huge stocks with the government that has left very little surplus in markets.”

The procurement of food grains increased from 34.3 million tonnes in 2006-2007 to 63.4 million tonnes in 2011-2012. Due to this the total stock of food grains in the central pool went up from 25.9 million tonnes as on June 1, 2007 to 82.4 million tonnes on June 1, 2012. The total stock of food grains that is held by the FCI, state governments and their agencies, is referred to as the central pool.

As on March 1, 2013, this number stood at 62.8 million tonnes. Analysts expect this to touch 100 million tonnes after the current procurement season gets over. FCI estimates put the carrying cost for this inventory comes at Rs 6.12 per kg. At 100 million tonnes, the cost works out to over Rs 60,000 crore.

And all this has happened because of high MSPs being set by the government. What is interesting is that the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India in a recent report titled “Performance Audit of Storage Management and Movement of Food Grains in Food Corporation of India (FCI)” questions the logic behind how the MSPs are being set.

The report was presented to the Parliament on May 7 ,2013. As the report points out “No specific norm was followed for fixing of the Minimum Support Price (MSP) over the cost of production. Resultantly, it was observed the margin of MSP fixed over the cost of production varied between 29 per cent and 66 per cent in case of wheat, and 14 per cent and 50 per cent in case of paddy during the period 2006-2007 to 2011-2012. Increase in MSP had a direct bearing on statutory charges levied on purchase of food grains by different State Government… All this resulted in rising of the acquisition cost of food grains.”

The high MSPs have led to another distortion. FCI majorly procures its rice and wheat from states like Punjab and Haryana. But over the last few years high MSPs have motivated various state governments to set up more and more procurement centres. A good example is Madhya Pradesh, which emerged as the second largest procurer of wheat last year by having set up more procurement centres over the years and by also offering a bonus to the farmers over and above the MSP. This year Bihar seems to have got into the act. As a recent editorial in the Business Standard points out “Bihar, only a marginally wheat surplus state, has this year set up more grain procurement centres than the major wheat-growing states of Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh put together.”

So the moral of the story is that both the central and state government are procuring more and more of the rice and wheat that is being produced, distorting the rice and wheat market totally. As V S Vyas an economist with the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council told Business Today “Stock in the market is important, not the total stock.”

It is unlikely that the MSP are going to come down this year given that Lok Sabha elections are due next year and hence the Congress led UPA will continue to offer ‘boon-dongles’ to citizens of this country. And even though the global production of rice and wheat is likely to go up as suggested by The Times of India, there will be no relief for the Indian consumer.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on May 13, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Rice

10 reasons why Amartya Sen is wrong about the food security bill

Vivek Kaul

Amartya Sen, who won the Nobel Prize for economics, in 1998, has been a big votary of the Food Security Bill being passed. “The case for passing this Bill is overwhelming…I would prefer this Bill to not having a Bill at all,” Sen said at a press conference yesterday.

The bill envisages to distribute highly subsidised rice and wheat to almost two-thirds of India’s population of 1.2 billion. In terms of its sheer size, this would be perhaps the biggest ever programme to distribute subsidised food grain to citizens of any country. And given this it is more than likely to have consequences, which the government of the day is either not thinking about or is simply not bothered about.

Given these consequences, Sen’s support for the Bill seems more ideological than logical. This conclusion can be easily drawn after a quick reading of a report titled National Food Security Bill: Challenges and Options authored by Ashok Gulati, Jyoti Gujral and T.Nandakumar (with Surbhi Jain, Sourabh Anand, Siddharth Rath, and Piyush Joshi) belonging to the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), which is a part of the Ministry of Agriculture. This report was released in December 2012.

The report highlights many reasons on why the Bill in its current form is a recipe for sheer disaster and is not desirable at all, and should be junked at the earliest opportunity.

1. The expenditure behind the food security bill is stated to be at Rs 1,20,000 crore. But this the CACP report feels is just the tip of the iceberg. This expenditure does not take into account “additional expenditure (that) is needed for the envisaged administrative set up, scaling up of operations, enhancement of production, investments for storage, movement, processing and market infrastructure etc.”

So what is the likely cost of the food security bill going to be? “The total financial expenditure entailed will be around Rs 682,163 crore over a three year period,” the report estimates. This is much higher than the Rs 1,20,000 crore per year estimate being made by the government. The question is where is this money going to come from? The government is already reeling under a very high fiscal deficit and is under pressure from international rating agencies to cut down on flab. A high fiscal deficit also means higher interest rates as the government will have to borrow more. It will also lead to higher inflation.

2. Estimates made by CACP suggest that over the next three years the cost of distributing rice and wheat at a subsidised price is going to come to Rs 5,12,428 crore. This calculation does not include other costs of creating the required infrastructure to run the scheme. Of this, the leakage is expected to be at 40.4%. So, nearly Rs 2,07,000 crore will be siphoned off by middlemen.

What is ironical is that the government wants to introduce the right to food security through its public distribution network rather than use a cash transfer system like Aadhar, which it has been creating parallely. The government’s public distribution system is perhaps the biggest distribution system of its kind in the world. But it has virtually collapsed in several states leading to huge leakages.

“It may be noted that this Bill is being brought in the Parliament to enact an Act when internationally, conditional cash transfers (CCTs), rather than physical distribution of subsidised food, have been found to be more efficient in achieving food and nutritional security,” the report points out.

3. The food security bill in its current forms works with the assumption that cereals like rice and wheat are central to the issue of food security. Rice and wheat will be made available at extremely subsidised prices as a part of right to food security. But the irony is that more and more Indians have moved away from cereals towards a protein based diet in the recent years.

As the report points out “As economic growth picks up, it is common to observe a change in dietary patterns wherein people substitute cereals with high-value food…Share of expenditure on cereals in total food expenditure has declined from 41% in 1987-88 to 29.1% in 2009-10 in rural areas and from 26.5% in 1987-88 to 22.4% in 2009-10 in urban areas. The Bill’s focus on rice and wheat goes against the trend for many Indians who are gradually diversifying their diet to protein-rich foods such as dairy, eggs and poultry, as well as fruit and vegetables. There is a need for a more nuanced food security strategy which is not obsessed with macro-level food-grain availability.”

4. A nuanced strategy is also needed because the right to food security also aims at improving the nutritional status of the population especially of women and children. But just ensuring that women and children have access to subsidised wheat and rice is not going to take care of this. As the report points out “Women’s education, access to clean drinking water, availability of hygienic sanitation facilities are the prime prerequisites for improved nutrition. It needs to be recognised that malnutrition is a multi-dimensional problem and needs a multi-pronged strategy.”

5. The right to food security creates a legal obligation for the government to distribute rice and wheat to those who are entitled. In order to fulfil this obligation the government will have to procure rice and wheat from the farmers. It currently does that through the Food Corporation of India(FCI) at a minimum support price(MSP). The MSP is declared in advance and the farmer knows what price he is going to get for the rice and wheat that he sells to the government.

The way the current system works is that FCI is obligated to buy all the rice or wheat that the farmer wants to sell as long as a certain quality standard is met. This has led to a situation where farmers find it favourable to produce rice and wheat because they have a ready buyer for all their produce, at a price they know in advance.

This has led to a severe imbalance in the production of oil seeds as well as pulses. As the report points out “India imported a whopping US$ 9.7 billion (Rs 46,242 crore) worth of edible oils in 2011-12 – a 47.5 percent jump from last year and pulses worth US$ 1.8 billion (Rs 8767 crore) during 2011-12- an increase of 16.4 percent as compared to last year.”

To distribute rice and wheat under the right to food security the government will continue using FCI and keep declaring a minimum support price. This means farmers will continue to get assured procurement when it comes to wheat and rice. And this will have several consequences. As the report points out “Assured procurement gives an incentive for farmers to produce cereals rather than diversify the production-basket…Vegetable production too may be affected – pushing food inflation further.”

6. Indian agriculture is still highly dependent on rainfall with 50% of area under cultivation still at the mercy of good monsoons. Irrigation wherever its available is also dependent on rainfall. So what happens in a situation of drought? As the report points out “A case in point is the drought year 2002-03 where the production of wheat and rice fell by 28.5 million tonnes over the previous year (overall food-grain production dropped by 38 million tonnes). It took 3 years to make up and it was only in 2006-07 that the production exceeded the 2001-02 level.”

If a drought situation crops up, will the government resort to imports? Is it a feasible option? Turns out it is not. “Rice is a very thinly traded commodity, with only about 7 per cent of world production being traded and five countries cornering three-fourths of the rice exports. The thinness and concentration of world rice markets imply that changes in production or consumption in major rice-trading countries have an amplified effect on world prices..This is especially true in the case of rice, as global markets are much smaller. India’s entry into the international market as a large buyer could exert significant upward pressure on prices,” the CACP report points out. Hence, any shortage of rice in India, is going to send world prices of rice through the roof. Also if the government continues procuring as much in a drought year as it has in previous years, it will leave very little of rice and wheat available for the open market, sending their prices through the roof.

7. The right to food security will mean that the government will use its public distribution system to distribute rice and wheat throughout the country. The trouble is that FCI, currently procures a major portion of rice and wheat from a few selective states. “70% of rice procurement is done from Punjab, AP, Chhattisgarh and UP while 80% of wheat procurement is done from Punjab, Haryana and MP alone,” the report points out. This will need infrastructure to be created and that will cost money.

As the report points out “From a logistics point of view it could be cheaper to procure food-grains from states like MP, Bihar, Gujarat etc and deliver the food-grains to neighbouring deficit states in central, eastern and western India rather than procure from a handful of surplus states in North and South and distribute food-grains across the deficit states in India. But such a system would need ramping up of procurement efforts in emerging surplus or self-sufficient states in cereals, such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Assam, and Orissa.” And that is easier said than done.

8. In many such states where the operations of FCI are huge, the government has become the number one procurer of rice and wheat. With right to food security coming in, this procurement is only going to go up. And that will create its own share of problems. “In several states like Punjab, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh, one observes that the state is overwhelmingly dominant in procuring rice and/or wheat, leading to almost a situation of monopsony. Any further increase in procurement by the state would crowd out private sector operations with an adverse effect on overall efficiency of procurement and storage operations, as well as on magnitude of food subsidies and open market prices,” the CACP report points out.

9. What has also been observed that FCI does not have economies of scale. As it procures more, its cost of procurement goes up. As the CACP report points out “The economic cost of procurement to Food Corporation of India (FCI) has been increasing over time with rising procurement levels – demonstrating that it suffers from diseconomies of scale with increasing levels of procurement. Currently, the economic cost of FCI for acquiring, storing and distributing foodgrains is about 40 percent more than the procurement price.” If right to food security becomes an Act, FCI’s procurement of rice and wheat will go up, and so will its cost of procurement. This will mean a higher expenditure on part of the government.

10. The government will also have to keep increasing the MSP it offers on rice and wheat. This will have to be done to incentivise farmers to produce more rice and wheat to help the government distribute it to the entitled beneficiaries. The farm labour costs have been on their way up. As the report points out “There is an acute shortage of labour in agriculture that has suddenly cropped up in these three years. In some states, labour costs have gone up by more than 100% over the same period. Due to these rising costs, the margins of production for farmers have been declining both for paddy and wheat . Therefore, the government may have to raise procurement prices for rice and wheat to encourage farmers to increase production of these staples. As the cost of production of crops is rising, MSP can’t be kept frozen.” This means that the government expenditure on right to food subsidy will keep going up.

To conclude, its time Amartya Sen read this report and made himself aware of the problems the right to food security can create for India.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on May 7,2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Right to food security will make things more difficult for salaried middle class

Vivek Kaul

There are no free lunches in life, though at times its not obvious who is footing the bill. Take the case of the right to food security bill which guarantees 80 crore Indians or two thirds of the population, subsidised rice, wheat and cereals.

The bill proposes to provide 5 kg of food grains to an individual every month at the rate of Rs 3 per kg of rice, Rs 2 per kg of wheat and Rs 1 per kg of cereals. The food minister KV Thomas expects that the extra burden on food subsidy will be about Rs 20,000 crore. Also 61.23 million tonnes of food grain would be needed.

Prima facie this is a very noble idea. But the question is who will be footing the bill for this? The answer is the tax paying salaried middle class. Allow me to explain.

In the financial year 2011-2012 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2011 and March 31,2012) the Indian government through the Food Corporation of India(FCI) and other agencies procured 63 million tonnes of grains (primarily rice and wheat).

If the right to food security bill is passed by the Parliament (as it is likely to be, why would any political party in their right sense oppose it?), the government will have to procure a greater amount of grains. The government estimates suggest that 61.23 million tonnes of food grain will be needed just to meet the requirements of the right to food security. There are other government food programmes running as well, and hence the 63 million tonnes of grain that the government currently procures may not be enough.

So the government will have to buy a greater amount of grain in the coming years. In order to do that it will have to keep offering a higher price. The government sets a minimum support price(MSP) for wheat and rice (and other agricultural commodities as well) every year and this has been going up over the last few years.

FCI and other state agencies acting on the government’s behalf buy grains produced by the farmer at the MSP. In the years to come the government is likely to buy more rice and wheat at a higher MSP. This means a lesser amount of rice and wheat will land up in the open market and thus push up prices. This argument does not work only if the amount of rice and wheat being produced goes up significantly and that cannot happen immediately in the short run.

Who does this hurt the most? The tax paying salaried middle class is the answer as they will have to pay more and more for the food that they buy.

There are other problems as well. The total storage capacity of FCI as on April 1, 2012, stood at 33.6 million tonnes. The Central Warehousing Corporation has 466 warehouses with a total capacity of 10.56 million tonnes. This brings the total storage capacity of the central government to a little over 44 million tonnes. Then there is the storage capacities of various state warehousing corporations which are also used to store grains. But even with that the government does not have enough storage capacity to store the amount of grain that it currently procures and will have to procure from the farmers in the years to come.

This means more grains will be dumped in the open and will rot as a result. As The Indian Express wrote in an editorial yesterday “The government will be required to procure more foodgrain at a huge cost, which would require pushing procurement prices even higher, creating storage facilities, and distributing the partly rotted foodgrain through a dysfunctional public distribution system.”

So more rotten food grain will be distributed in the years to come.

The major reasoning behind right to food security is that if subsidised food is offered to people, their nutrition will improve. This is not always the case. Abhijit Banerjee, professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology explains this through an example. “We carried out a nice experiment in China. We gave some people a voucher to buy cheap rice. Instead of buying rice lets say for Rs 10, they could buy it for Rs 2, using the vouchers. The presumption was that this would improve nutrition. This was done as an experiment and hence some people were randomly given vouchers and others were not. When people went back and looked at it, they were astounded. People with vouchers had were worse off in nutrition. They felt that now that they have the vouchers, they are rich and no longer need to eat rice. They could eat pork, shrimps etc. They went and bought pork and shrimps and as a result their net calories went down. This is perfectly rational. These people were waiting for pleasure.”

A similar thing might play out in India as well. The money people will save on buying subsidised rice/wheat, might get channelised onto other unhealthy alternatives. But then that’s an individual decision that people might make and hence needs to be left at that.

The broader point is there hasn’t been enough discussion/debate/trials to figure out the unintended consequences of the right to food bill. One unintended consequence that is visible straight away is the rise in prices of non cereal food.

The money people save on buying rice/wheat can get channelised into buying fruit, vegetable, pulses, fish, meat, eggs etc. But the production for this may not go up at the same pace leading to higher price. As The Indian Express points out “The production of fruit, vegetable, pulses, fish, meat and eggs will continue to stagnate, however, as more resources will need to be allocated to push up the production of foodgrain. Instead of land, labour, capital, fertilisers and infrastructure being devoted towards meeting the needs of the population as determined by households that choose what they wish to eat, the country will be diverting resources to producing what the state decides the population must consume.”

As the government offers higher MSPs on rice and wheat, the farmers are more likely to produce that than non cereal food. This for the simple reason that the MSP is set in advance and it gives the farmer a good idea of how much he should expect to earn when he sells his produce a few months later. The same is not true for something like pulses where the government does set an MSP, but does not have the required infrastructure for procurement.

The “nutrition” problem will also continue. As Howarth Bouis , director of HarvestPlus, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Washington, pointed out in a recent interview to Mint “If you look at all the other food groups such as fruits, vegetables, lentils, and animal products other than milk, you will find a steady increase in prices over the past 40 years. So it has become more difficult for the poor to afford food that is dense in minerals and vitamins. That probably explains the poor nutritional outcomes .” The right to food security will ensure that the poor will find it even more difficult to buy non cereal food which is high on nutrition as it becomes more expensive.

The nutrient deficit of India will continue to remain unaddressed. The right to food security works with the assumption that most of India’s poor may not have access to even the most basic food. That is really not correct as the government’s own data shows. As The Mint points out in a recent news report “Apart from the extremely poor, who form a small fraction of the population, nearly everyone else can afford the rice and wheat they require… A February report of the National Sample Survey Office shows the proportion of people not getting two square meals a day dropped to about 1% in rural India and 0.4% in urban India in 2009-10. Interestingly, the average cereal consumption of families who reported that they went hungry in some months of the year (in the month preceding the survey) was roughly equal to the average cereal consumption of those who reported receiving adequate meals throughout the year. The stark difference across income-classes lies in the level of spending on non-cereal food items, the survey points out.”

So what India needs to eat is more of eggs, vegetables and fruits, and not rice and wheat, as the government seems to have decided to. “Most of the poor can afford as much of rice, or wheat, as they can eat. And if you look at consumption patterns of these items across income groups, it does not change very much. The huge difference between low-income and high-income groups is in the consumption of non-staple foods—fruits, vegetables and pulses. I think that’s what is limiting better nutrition, not just in India but in much of the developing world,” Bouis told Mint.

What all this means is that the right to food security will drive up food prices higher than what they already are. Hence, food inflation will continue to remain high, which in turn will push up consumer price inflation as well. The right to food security will not only hurt those it is intended to benefit, but it will also hurt the tax paying salaried middle class, as they will continue to face higher prices on food.

The passing of right to food also signals that the Congress led UPA government remains committed to higher expenditure, without really figuring out where the revenue to finance that expenditure is going to come from. In simple English that means the government is going to continue to borrow more. Banks will thus have a lower pool of savings to borrow from, which means higher interest rates and higher EMIs will continue. Now who does this hurt the most? The tax paying middle class again.

Estimates made by Global Financial Integrity suggest that between 2001 and 2010, nearly $123 billion of illicit financial flows went out of India. This means around $12 billion per year on an average. At current conversion rate of one dollar being worth around Rs 54, this is around Rs 65,000 crore per year. So Rs 65,000 crore of black money is leaving the country every year. The black money being generated within the country would be many times over.

Of course people who have this black money are better placed to bear inflation because they don’t pay tax. That is clearly not the case with the salaried middle class, who pay tax and also have to bear higher food inflation. The government should be looking at ways of taxing this black money.

Over and above this agricultural income in this country continues to remain untaxed. This is totally bizarre. As Andy Mukherjee of Reuters Breaking Views writes in a slightly different context “No government today can muster the political courage to tax the incomes of even very large farmers. But to keep the section of the economy that accounts for 60 percent of employment out of tax undermines the system’s legitimacy…It’s ironic that villagers should have political representation without taxation, while the urban middle class finds itself heavily taxed but politically alienated.”

Taxing agricultural income remains out of question. Meanwhile, the salaried tax paying middle class will continue to be screwed.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on March 20, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

UPA-nomics: How to hoard grain and let food prices soar

Vivek Kaul

Over the last few days my mother and her sister have been complaining about how the price of the 10 kg bag of rice that they buy has gone up by 17% in just over a couple of month’s time.

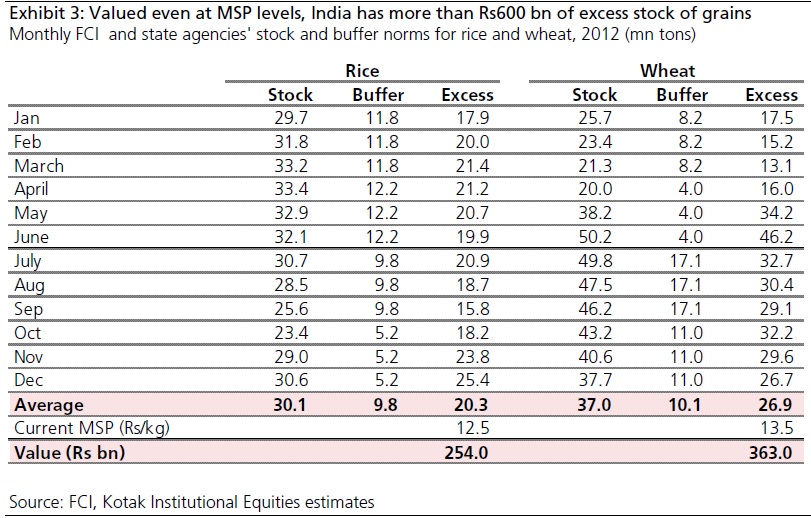

Now contrast this with what Akhilesh Tilotia of Kotak Institutional Equities Research writes in the GameChanger Perspectives report titled Putting the mountain of grains to use (Released on March 5, 2013). “India can raise more than Rs60,000 crore if it prunes its inventory of food grains: an excess 20 million tons of rice and 26 million tons of wheat (without accounting for procurements to be made this year),” writes Tilotia. (The table shows the numbers in detail).

As the above table shows the government currently has an excess rice stock worth around Rs 25,400 crore and an excess wheat stock worth Rs 36,300 crore, or more than Rs 60,000 crore in total. These numbers have been arrived at by taking into account the MSP of rice at Rs 12.5 per kg and the MSP of wheat at Rs 13.5 per kg and multiplying them with the excess stocks. What the table also tells us is that the government currently has an excess rice stock of nearly 2 times the buffer and an excess wheat stock of nearly 2.7 times the buffer.

The government sets a minimum support price(MSP) for wheat and rice. Every year the Food Corporation of India (FCI), or a state agency acting on its behalf, purchases rice and wheat at MSPs set by the government. The “supposed” idea behind setting the MSP much and that too much in advance is to give the farmer some idea of how much he should expect to earn when he sells his produce a few months later. FCI typically purchases around 15-20 percent of India’s wheat output and 12-15 percent of its rice output, estimates suggest.

At least this is how things are supposed to work in theory. But most government motives have unintended consequences. With an assured price more rice and wheat lands up with the government than it distributes through the public distribution system. Also with FCI obligated to purchase what the farmers bring in, its godowns overflow and at times the wheat and rice are dumped in the open, leading to rodents feasting on the crop.

On the other hand the way things currently are it helps the farmer as he has an assured buyer in the government for his produce. But what it also does is it pushes up prices of rice and wheat everywhere else, as more of it lands up in the godowns of FCI and not in the open market.

The procurement also adds to the food subsidy. The government pays for all the rice and wheat that the farmer brings to it and then lets a lot of it rot. The government currently has nearly 67 million tonnes of rice and wheat in stock. Of this nearly 47 million tonnes is excess.

Tilotia expects the rice and wheat stock of the government to go up to 100 million tonnes by the time this harvest season gets over. As he writes “After the current harvest season, Indian granaries will stock about 100 million tonnes of wheat and rice…A high inventory comes with a heavy carrying cost, which the FCI estimates at Rs6.12 per kg for year-end September 2014: At 100 million tons, this will cost India Rs 60,000 crore a year (forming most of its food subsidy bill).”

A higher food subsidy bill adds to the fiscal deficit and which as writers Firstpost regularly keeps discussing has huge consequences of its own. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government spends and what it earns.

In fact, the United States of America had a similar policy in place in the aftermath of The Great Depression which started in 1929, on a number of agri-commodities like wheat, tobacco, cotton etc. The government offered a support price to farmers. This support price had unintended consequences over the years, especially in case of wheat.

As Bruce Gardner writes in the research paper “The Political Economy of U.S.Export Subsidies for Wheat” (quoted by Tilotia) “The traditional means of price support is a governmental agreement, through its Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC), to buy wheat at the support price. This programme periodically led to governmental acquisition of large stocks which were costly to store and for which markets did not exist at the support price level.”

As is happening in India right now the American government ended up buying more and more wheat, of which it had no use for, especially at the price it was paying for it. The farmers had an assured buyer in the government and they went around producing more wheat than before.

This resulted in excess stocks with the American government. Over the years this excess wheat was exported at a subsidised rates. As Gardner writes “The subsidy ranged from 5 to 30 percent of the price of wheat, depending on world and U.S. market conditions in each year.” A lot of wheat was also donated under the Agricultural Trade and Development Act of 1954 ( better known as P.L. 480) of which India was a huge beneficiary in the late 50s and early 60s till Lal Bahadur Shastri initiated the agricultural revolution.

Gradually the wheat acreage, or the area over which wheat was planted, was also reduced in the United States. This meant that the farmers had to keep their land idle and not plant wheat on it. “Acreage allotments…were reintroduced in 1954 and reduced planted acreage by about 18 million acres (from 79 million in 1953 to an average of 61 million in 1954-56). Each producer had to stay under the farm’s allotment in order to be eligible for price support loans. In 1956 the Soil Bank program was introduced. It paid wheat growers about $20 per acre (roughly market rental rates) to idle an average of 12 million more acres (20 percent of preprogram acreage) in 1956-58,” writes Gardner.

India seems to be heading on the same path if the current policies don’t change. As Tilotia writes “India’s inventory is concentrated in the north-western states of Punjab and Haryana, which store 36 million tons of its 66 million tons of stock. Given the large procurement expected from these states again this year (though Madhya Pradesh may better Haryana in wheat procurement this year, especially given state elections), this imbalance can worsen.”

Interestingly, the government can use this excess inventory of rice and wheat to control inflation and at the same time bring down its fiscal deficit. The government currently has rice and wheat worth in excess of Rs 60,000 crore. On the other hand it also has a disinvestment target of Rs 54,000 crore for the next financial year (i.e. the period between April 1, 2013 and March 31, 2014). The government hopes to earn this amount by selling stakes it holds in public sector units to the public.

Along similar lines the government can try selling the excess rice and wheat that it currently holds in the open market. This will help control food inflation with the excess government stock hitting the market. Food forms around 43% of the consumer price inflation number and so if food inflation comes down, the consumer price inflation is also likely to come down.

The challenge of course in doing this is two fold. The first being moving grains from Punjab, Haryana where more than half the inventory lies. The second is to ensure that the market prices of rice and wheat don’t collapse.

Also the current MSP system is not working. If the idea is to pay the citizens of this country to improve their living standards, the government may be better off paying them in cash, rather than paying them in this roundabout manner that creates inflation. This is simply because the current system drives up the price of food for everyone else and it doesn’t necessarily always benefit the farmers. The middleman continue to make the most money.

As Tilotia puts it “If such a payment indeed needs to be made, there is no point in raising prices for all in the system by adding it to the price of the grain: Simply pay the farmer whatever support you want to pay him/her. India is reaching a situation where, by using UID it would be able to send payments to farmers directly. Maybe it is time to re-couple wheat and rice prices with global prices – that can meaningfully reduce inflation in India.”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on March 6,2013.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

The difficulty of being Duvvuri Subbarao

Vivek Kaul

Decisions are of two kinds. The right one. And the one your boss wants you to make. The twain does not always meet.

Duvvuri Subbarao, the governor of the Reserve Bank of India(RBI), earlier this week, showed us what a right decision is. He decided to hold the repo rate at 8%. Repo rate is the interest rate at which RBI lends to banks. There was great pressure on the RBI governor to cut the repo rate, after the gross domestic product (GDP) growth for the period between January and March 2012 came in at a very low 5.3%.

The Finance Minister, Pranab Mukherjee, declared openly that he was “confident that they (the RBI) will adjust the monetary policy,” which basically meant that he was ordering the RBI to cut the repo rate. The idea was that once the RBI cut the repo rate, banks would also cut interest rates leading to consumers borrowing more to buy homes, cars and durables. Businesses would borrow more to expand and in turn push up economic growth.

But economic theory and practice are not always in line. Subbarao, probably understands this much better than others, though until very recently he had largely stuck to doing what his boss the Finance Minister, wanted him to do. For the first time he has shown signs of breaking free.

The credibility of a repo rate cut

By cutting the repo rate the Reserve Bank essentially tries to send out a signal to banks that it expects interest rates to come down in the days to come. If banks think the signal is credible enough then they cut the interest rates they pay on their deposits as well as the interest rates they charge on their long term loans like home loans, car loans and loans to businesses. But the trouble is that even if the RBI cut the repo rate, the credibility of the signal would be under doubt, and banks wouldn’t have been able to cut interest rates.

Between the six month period of December 2, 2011, and June 1, 2012, banks have given loans amounting to Rs 4,46,563 crore and have borrowed Rs 4,27,709 crore. Hence for every Rs 100 that the banks have borrowed they have lent out Rs 104, which means they have not been able to raise enough deposits during to match their loans. So their ability to cut interest rates is limited. The question is why is the money situation so tight?

High fiscal deficit

The government of India has been running a very high fiscal deficit. For the financial year 2007-2008, the fiscal deficit stood at Rs 1,26,912 crore. It shot up to Rs 5,21,980 crore for 2011-2012. In a time frame of five years the fiscal deficit is up nearly 312%. The income earned by the government has gone up by only 36% to Rs 7,96,740 crore, during the same period. The huge increase in fiscal deficit has primarily happened because of the subsidy on food, fertilizer and petroleum. For the current financial year, the fiscal deficit is projected to be at Rs 5,13,590 crore, which is likely to be missed as has been the case in the last few years. The oil subsidy targets have regularly been overshot. This year the government might even overshoot the food subsidy target of Rs 75,000 crore.

The government finances its fiscal deficit by borrowing. When a government borrows more, as has been the case for the last few years, it ‘crowds out’ the other big borrowers like banks and corporates. This means that the ‘pool of money’ from which banks and companies have to borrow comes down. Hence, they have to offer a higher rate of interest. This is the situation which prevails now. So banks will continue in the high interest rate mode.

High inflation

What must have also influenced Subbarao’s decision is the high inflationary which prevails. The consumer price inflation for the month of May stood at 10.36%. This is likely to go up even further in the days to come given that the government recently increased the minimum support price(MSP) on khareef crops from anywhere between 15-53%. These are crops which are typically sown around this time of the year for harvesting after the rains. The MSP for paddy (rice) has been increased from Rs 1,080 per quintal to Rs 1,250 per quintal. Other major products like bajra, ragi, jowar, soybean etc, have seen similar increases. This will further fuel food inflation. Also, after dramatically increasing prices for khareef crops, the government will have to follow up the same for rabi crops like wheat. Rabi crops are planted in the autumn season and harvested in winter. Economists expect higher MSP on agriculture products to push up the food subsidy bill by Rs 40,000 crore from its current level of Rs 75,000 crore. This means a higher fiscal deficit and in turn higher interest rates.

To conclude

In a scenario where the inflation is over 10%, cutting interest rates can fuel further inflation, which isn’t good for anyone. The RBI in a release said that the inflation is “driven mainly by food and fuel prices.” That’s something Subbarao cannot do anything about and is for the government to sort out.

“In the absence of pass-through from international crude oil prices to domestic prices, the consumption of petroleum products remains strong…preventing the much needed adjustment in aggregate demand,” the RBI release said. The Subbarao led RBI seems to be clearing telling the government here to cut down on oil subsidies by increasing fuel prices as and when necessary.

In fact in a rare admission Subbarao even said that the last cut in the repo rate in April may have been a mistake. “The Reserve Bank had frontloaded the policy rate reduction in April with a cut of 50 basis points. This decision was based on the premise that the process of fiscal consolidation critical for inflation management would get under way, along with other supply-side initiatives,” the RBI release said.

What this means in simple English is that the RBI may have been led to believe by the finance ministry that if they went ahead and cut the repo rate in April, the government would follow up by taking emasures to cut the fiscal deficit. But that hasn’t happened. RBI kept its part of the deal. The government did not.

The article originally appeared in the Times of India Crest Edition on June 23,2012.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])