Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

Raghuram Rajan, the governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) surprised everybody today, by choosing to not raise the repo rate. The repo rate will continue to be at 7.75%. Repo rate is the rate at which the RBI lends to banks.

Economists had been predicting that Rajan will raise the repo rate in order to rein in inflation. The consumer price inflation(CPI) for the month of November 2013 was at 11.24%. In comparison the number was at 10.17% in October 2013. The wholesale price inflation(WPI) number for November 2013 came in at 7.52%. In comparison the number was at 7% in October 2013.

As Taimur Baig and Kaushik Das of Deutsche Bank Research wrote in a note dated December 16, 2013 said “The upside surprise in both CPI and WPI inflation for November leaves no option for RBI but to hike the policy rate(i.e. the repo rate) by 25basis points in Wednesday’s monetary policy review, in our view.”

Along similar lines Sonal Varma, India economist at Nomura, told CNBC.com that she expected the RBI to increase the repo rate by 25 basis points(one basis point is one hundredth of a percentage). But Rajan has chosen to stay put and not raise the repo rate.

Why is that the case? The answer lies in looking at the inflation numbers in a little more detail. The consumer price inflation is primarily being driven by food inflation. Food (along with beverages and tobacco) accounts for nearly half of the index. Food inflation in November 2013 as per the CPI stood at 14.72%. Within food inflation, vegetable prices rose by 61.6% and fruit prices rose by 15%, in comparison to November 2012.

So what this tells us very clearly is that consumer price inflation is being driven primarily by food inflation. In fact, this is something that the WPI data also clearly shows. The food inflation as per WPI was at 19.93%. Within it, onion prices rose by 190.3% and vegetable prices rose by 95.3%.

The RBI expects vegetable prices to fall. Baig and Das in a note dated December 18, 2013, said “vegetable prices, key driver of inflation in recent months, have started falling in the last couple of weeks (daily prices of 10 food items tracked by us are down by about 7% month on month(mom) on an average in the first fortnight of December).”

In case of WPI, food articles have a much lower weightage of around 14.33%. The other big contributor to WPI was fuel and power, in which case the inflation was at 11.08%. This is primarily on account of diesel and cooking gas prices being raised regularly in the recent past.

So inflation is primarily on account of two counts: food and fuel prices going up. The Reserve Bank of India cannot do anything about this. And given that raising the repo rate would have had a limited impact on high inflation.

In fact, if one looks at the WPI data a little more carefully, there is a clear case of the economy slowing down. Manufactured products form a little under 65% of the wholesale price inflation index. The inflation in case of manufactured products stood at 2.64% in November 2013.

When people are spending more and more money on buying food. They are likely to be left with less money to buy everything else. In this scenario they are likely to cut down on their non food expenditure.

And this has an impact on businesses. When the demand is not going up, businesses are not in a position to increase prices. And that is reflected in the manufacturing products inflation of just 2.64%. It was at 5.41% in November 2012.

Interestingly, the high cost of food should translate into the cost of labour going up. At the same time, energy prices are also going up. This is reflected in the fuel and power inflation of 11.08%. But businesses have not been able to pass through these increases in the cost of their inputs, by raising the price of their final products. This is primarily because of the lack of consumer demand.

The lack of consumer demand is also reflected in the index of industrial production(IIP), a measure of industrial activity. For October 2013, IIP fell by 1.8% in comparison to the same period last year. If people are not buying as many things as they used to, there is no point in businesses producing them.

In this scenario, raising interest rates would mean that people looking to borrow and spend money to buy goods, will have to pay higher EMIs. Businesses looking to borrow money and expand will also have to pay more. And this turn impacts economic growth. As the RBI’s statement today put it “The weakness in industrial activity persisting into Q3, still lacklustre lead indicators of services and subdued domestic consumption demand suggest continuing headwinds to growth.”

In this scenario the Rajan led RBI decided to keep the repo rate constant. What is interesting is that the RBI’s statement has suggested that it might raise the repo rate if the food inflation does not fall as it is expected to. “If the expected softening of food inflation does not materialise and translate into a significant reduction in headline inflation in the next round of data releases, or if inflation excluding food and fuel does not fall, the Reserve Bank will act, including on off-policy dates if warranted,” the statement said.

Effectively, the RBI has bought some time. “The RBI has effectively given itself a one-month window to see if inflation actually eases in December to decide on future monetary policy action,” wrote Baig and Das of Deutsche.

In fact, Raghuram Rajan’s decision not to raise the repo rate has been seen as a surprise primarily because he has made several comments in the public saying that inflation was running higher than the comfort level. Also, Rajan is seen as an inflation fighter, and by not raising the repo rate, he has put that image at risk.

As Robert Prior-Wandesforde, director of Asian economics research at Credit Suisse, recently wrote “The data pose the now familiar dilemma for the central bank. While the direct effect of interest rate hikes on inflation is debatable, particularly when food prices are such an important driver, we very much doubt Dr. Rajan can be seen to be sitting on his hands at this stage …”To do so, would be take risks with his inflation fighting credentials,” he added.

It is hard to believe that Rajan will these credentials at risk. And given that we might just see a repo rate hike early in the new year.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on December 18, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Food inflation

Falling rural wages punches holes in UPA’s NREGA claims

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

One of the so called successes of the Congress led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government has been the increase in rural incomes. As Ashok Gulati, Surbhi Jain and Nidhi Satija of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) of the Ministry of Agriculture point out in a research paper titled Rising Farm Wages in India “During the Eleventh Five year Plan (2007‐12), nominal farm wages in India increased by 17.5 per cent per annum (p.a), and real farm wages by 6.8 per cent p.a., registering the fastest growth since economic reforms began in 1991.”

Hence, rural incomes have been growing at a very fast rate through much of the second term of the UPA government. And the UPA politicians have pointed this out time and again. Yes, urban India is feeling the heat, but that is the price we need to pay to ensure that rural India is in a better situation than it was in the past, is an argument we have been made to hear time and again.

But looks like time has run out for this argument as well. Rural wages after adjusting for inflation fell in August 2013. As Sonal Varma of Nomura points out in a note dated October 24, 2013 “Growth in the average daily wage rate for agricultural labourers moderated to 13.1% y-o-y in August 2013, significantly slower than 18.5% y-o-y in 2012 and 23.4% in 2011. After adjusting for inflation, the decline was even more stark: real rural wage growth moderated to -0.1% y-o-y in August from 9.3% y-o-y in 2012 and 13.4% in 2011.” (y-o-y = year on year)

A real rural wage growth of -0.1% basically means that the income is growing just about at the same speed so as to match inflation. And this can’t be a good sign for sure.

One of the major reasons for an increase in rural wages has been Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act(MGNREGA). As the CACP authors point out “The argument forwarded is that MGNREGA has ‘pushed’ up the average wage of casual workers, distorted the rural labour markets by diverting them to non‐farm rural jobs, thus creating an artificial labour shortage.” And this shortage has in turn pushed up rural wages to a large extent.

As Varma points out “Several factors, including the government’s employment guarantee scheme(which is MGNREGA) and indexing rural wages to CPI inflation, have boosted rural wage growth and shifted the terms of trade in favour of the rural sector.”

MGNREGA was launched in 200 of the most backward districts of the country on February 2, 2006. It was extended to all rural districts from April 1, 2008. The scheme aims at providing at least 100 days of guaranteed employment in a financial year to every household whose adults are willing to do unskilled manual work.

The payments made under MGNREGA vary from Rs 120 to Rs 179 per day, depending on the state. As mentioned earlier these wages are indexed to inflation. “At the national level, with the average nominal wage paid under the scheme increasing from Rs 65 in FY 2006‐07 to Rs 115 in FY 2011‐12… It has set a base price for labour in rural areas, improved the bargaining power of labourers and has led to a widespread increase in the cost of unskilled and temporary labour including agricultural labour,” write the authors of the CACP report.

So far so good. If MGNREGA was creating useful assets then all this money would have been well spent. The trouble is it isn’t. T H Chowdhary provided an excellent example of why MGNREGA does not work in a column he wrote for The Hindu Business Line in December 2011 “Villages cannot sustain so many unskilled labourers and not-so-literate labour. By creating useless “work” we are promoting dependency among the unfortunate rural, illiterate and unskilled population…An example of the village Angaluru in Krishna district will illustrate how good money is being thrown away for bad results. Out of 1,000 families, 800 had registered themselves as BPL, seeking work under NREGA. So far, it was 100 days at Rs. 100 per day. Even at this, 80,000 mandays of useful work in a year is impossible in a village and that too, year after year.”

What this tells us is that the very structure of MGNREGA does not make sense (and we are not even talking about all the corruption that comes with such schemes). What is true about one Angaluru village in Andhra Pradesh is true about most of the other villages all across the country as well.

Hence, the government is effectively giving away money free to people who have registered under MGNREGA. As Chowdhary puts it “Those who are registered for NREGA are mustered just for attendance and since there is no work to be done they go home, thus paid for no or little work.”

When people get paid for doing no work it is but natural that they will demand much more money for working. This has led to a substantial increase in rural wages over the last few years.

And high wages have led to high inflation in turn, specially food inflation, as a higher amount of money chased the same amount of goods and services. Over the last few years, the wages had been rising at a much faster rate than inflation, but now inflation has finally caught up.

This will now have an impact on rural demand which has remained robust over the last few years, even though the overall economic growth has slowed down considerably. As Varma of Nomura puts it “Over the last few years, rising real rural wages have…supported rural demand… A moderation in real rural wages should cause rural demand to moderate.” This, in turn, will slowdown economic growth further in the time to come. On a positive note, a slowdown in rural demand will also lead to medium term inflationary pressures moderating.

The basic point is simple. Sustainable economic growth cannot be created by simply distributing money or as some economists like to put it by “dropping money from a helicopter”. Gurcharan Das summarises the situation best in India Grows At Night. As he writes “We need to be humbler in our ambition and our ability to re-engineer society…If the state could only enable access to good schools and health care, equity would follow.”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on October 25, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Food Security – The biggest mistake India might have made till date

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

Historians often ask counterfactual questions to figure out how history could have evolved differently. Ramachandra Guha asks and answers one such question in an essay titled A Short History of Congress Chamchagiri, which is a part of the book Patriots and Partisans.

In this essay Guha briefly discusses what would have happened if Lal Bahadur Shastri, the second prime minister of India, had lived a little longer. Shastri died on January 11, 1966, after serving as the prime minister for a little over 19 months.

The political future of India would have evolved very differently had Shashtri lived longer, feels Guha. As he writes “Had Shastri lived, Indira Gandhi may or may not have migrated to London. But even had she stayed in India, it is highly unlikely that she would have become prime minister. And it is certain that her son would have never have occupied or aspired to that office…Sanjay Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi would almost certainly still be alive, and in private life. The former would be a (failed) entrepreneur, the latter a recently retired airline pilot with a passion for photography. Finally, had Shastri lived longer, Sonia Gandhi would still be a devoted and loving housewife, and Rahul Gandhi perhaps a middle-level manager in a private sector company.”

But that as we know was not to be. Last night, the Lok Sabha, worked overtime to pass Sonia Gandhi’s passion project, the Food Security Bill. India as a nation has made big mistakes on the economic and the financial front in the nearly 66 years that it has been independent, but the passage of the Food Security Bill, might turn out to be our biggest mistake till date.

The Food Security Bill guarantees 5 kg of rice, wheat and coarse cereals per month per individual at a fixed price of Rs 3, 2, 1, respectively, to nearly 67% of the population.

The government estimates suggest that food security will cost Rs 1,24,723 crore per year. But that is just one estimate. Andy Mukherjee, a columnist with Reuters, puts the cost at around $25 billion. The Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices(CACP) of the Ministry of Agriculture in a research paper titled National Food Security Bill – Challenges and Optionsputs the cost of the food security scheme over a three year period at Rs 6,82,163 crore. During the first year the cost to the government has been estimated at Rs 2,41,263 crore.

Economist Surjit Bhalla in a column in The Indian Express put the cost of the bill at Rs 3,14,000 crore or around 3% of the gross domestic product (GDP). Ashok Kotwal, Milind Murugkar and Bharat Ramaswamichallenge Bhalla’s calculation in a column in The Financial Express and write “the food subsidy bill should…come to around 1.35% of GDP, which is still way less than the numbers he(i.e. Bhalla) put out.”

The trouble here is that by expressing the cost of food security in terms of percentage of GDP, we do not understand the seriousness of the situation that we are getting into. In order to properly understand the situation we need to express the cost of food security as a percentage of the total receipts(less borrowings) of the government. The receipts of the government for the year 2013-2014 are projected at Rs 11,22,799 crore.

The government’s estimated cost of food security comes at 11.10%(Rs 1,24,723 expressed as a % of Rs 11,22,799 crore) of the total receipts. The CACP’s estimated cost of food security comes at 21.5%(Rs 2,41,623 crore expressed as a % of Rs 11,22,799 crore) of the total receipts. Bhalla’s cost of food security comes at around 28% of the total receipts (Rs 3,14,000 crore expressed as a % of Rs 11,22,799 crore).

Once we express the cost of food security as a percentage of the total estimated receipts of the government, during the current financial year, we see how huge the cost of food security really is. This is something that doesn’t come out when the cost of food security is expressed as a percentage of GDP. In this case the estimated cost is in the range of 1-3% of GDP. But the government does not have the entire GDP to spend. It can only spend what it earns.

The interesting thing is that the cost of food security expressed as a percentage of total receipts of the government is likely to be even higher. This is primarily because the government’s collection of taxes has been slower than expected this year. The Controller General of Accounts has put out numbers to show precisely this. For the first three months of the financial year (i.e. the period between April 1, 2013 and June 30, 2013) only 11.1% of the total expected revenue receipts (the total tax and non tax revenue) for the year have been collected. When it comes to capital receipts(which does not include government borrowings) only 3.3% of the total expected amount for the year have been collected.

What this means is that the government during the first three months of the financial year has not been able to collect as much money as it had expected to. This means that the cost of food security will form a higher proportion of the total government receipts than the numbers currently tell us. And that is just one problem.

It is also worth remembering that the government estimate of the cost of food security at Rs 1,24,723 crore is very optimistic. The CACP points out that this estimate does not take into account “additional expenditure (that) is needed for the envisaged administrative set up, scaling up of operations, enhancement of production, investments for storage, movement, processing and market infrastructure etc.”

Food security will also mean a higher expenditure for the government in the days to come. A higher expenditure will mean a higher fiscal deficit. Fiscal deficit is defined as the difference between what a government earns and what it spends.

The question is how will this higher expenditure be financed? Given that the economy is in a breakdown mode, higher taxes are not the answer. The government will have to finance food security through higher borrowing.

Higher government borrowing by the government as this writer has often explained in the past crowds out private borrowing. The private sector (be it banks or companies) in order to compete with the government for savings will have to offer higher interest rates. This means that the era of high interest rates will continue, which will not be good for economic growth.

Also, it is important to remember that the food security scheme is an open ended scheme. As Nitin Pai, Director of The Takshashila Institution, writes in a column “The scheme is open-ended: there’s no expiry date, no sunset clause. It covers around two-thirds of the population—even those who are not really needy. This means that the outlays will have to increase as the population grows.”

This might also lead to the government printing money to finance the scheme. It was and remains easy for the government to obtain money by printing it rather than taxing its citizens. F P Powers aptly put it when he said that money printing would always be “the first device thought of by a finance minister when a large quantity of money has to be raised at once”. History is full of such examples.

Money printing will lead to higher inflation. Prices will rise due to other reasons as well. Every year, the government declares a minimum support price (MSP) on rice and wheat. At this price, it buys grains from farmers. This grain is then distributed to those entitled to it under the various programmes of the government.

The grain to be distributed under the food security programme will also be procured in a similar way. But this may have other unintended consequences which the government is not taking into account. As the CACP points out “Assured procurement gives an incentive for farmers to produce cereals rather than diversify the production-basket…Vegetable production too may be affected – pushing food inflation further.”

And this will hit the very people food security is expected to benefit. A discussion paper titled Taming Food Inflation in India released by CACP in April 2013 points out the same. “Food inflation in India has been a major challenge to policy makers, more so during recent years when it has averaged 10% during 2008-09 to December 2012. Given that an average household in India still spends almost half of its expenditure on food, and poor around 60 percent (NSSO, 2011), and that poor cannot easily hedge against inflation, high food inflation inflicts a strong ‘hidden tax’ on the poor…In the last five years, post 2008, food inflation contributed to over 41% to the overall inflation in the country.”

Higher food prices will mean higher inflation and this in turn will mean lower savings, as people will end up spending a higher proportion of their income to meet their expenses. This will lead to people spending a lower amount of money on consuming good and services and thus economic growth will slowdown further. It might not be surprising to see economic growth go below the 5% level.

Lower savings will also have an impact on the current account deficit. As Atish Ghosh and Uma Ramakrishnan point out in an article on the IMF website “The current account can also be expressed as the difference between national (both public and private) savings and investment. A current account deficit may therefore reflect a low level of national savings relative to investment.” If India does not save enough, it means it will have to borrow capital from abroad. And when these foreign borrowings need to be repaid, dollars will need to be bought. This will put pressure on the rupee and lead to its depreciation against the dollar.

There is another factor that can put pressure on the rupee. In a particular year when the government is not able to procure enough rice or wheat to fulfil its obligations under right to food security, it will have to import these grains. But that is easier said than done, specially in case of rice. “Rice is a very thinly traded commodity, with only about 7 per cent of world production being traded and five countries cornering three-fourths of the rice exports. The thinness and concentration of world rice markets imply that changes in production or consumption in major rice-trading countries have an amplified effect on world prices,” a CACP research paper points out. And buying rice or wheat internationally will mean paying in dollars. This will lead to increased demand for dollars and pressure on the rupee.

The weakest point of the right to food security is that it will use the extremely “leaky” public distribution system to distribute food grains. As Jagdish Bhagwati and Arvind Panagariya write in India’s Tryst With Destiny – Debunking Myths That Undermine Progress and Addressing New Challenges “A recent study by Jha and Ramaswami estimates that in 2004-05, 70 per cent of the poor received no grain through the pubic distribution system while 70 per cent of those who did receive it were non-poor. They also estimate that as much as 55 per cent of the grain supplied through the public distribution system leaked out along the distribution chain, with only 45 per cent actually sold to beneficiaries through fair-price shops. The share of food subsidy received by the poor turned out to be astonishingly low 10.5 per cent.”

Estimates made by CACP suggest that the public distribution system has a leakage of 40.4%. “In 2009-10, 25.3 million tonnes was received by the people under PDS while the offtake by states was 42.4 million tonnes- indicating a leakage of 40.4 percent,” a CACP research paper points out.

Bhagwati and Panagariya also point out that with the subsidy on rice being the highest, the demand for rice will be the highest and the government distribution system will fail to procure enough rice. As they write “recognising that the absolute subsidy per kilogram is the largest in rice, the eligible households would stand to maximize the implicit transfer to them by buying rice and no other grain from the public distribution system. By reselling rice in the private market, they would be able to convert this maximized in-kind subsidy into cash…Of course, with all eligible households buying rice for their entire permitted quotas, the government distribution system will simply fail to procure enough rice.”

The jhollawallas’ big plan for financing the food security scheme comes from the revenue foregone number put out by the Finance Ministry. This is essentially tax that could have been collected but was foregone due to various exemptions and incentives. The Finance Ministry put this number at Rs 480,000 crore for 2010-2011 and Rs 530,000 crore for 2011-2012. Now only if these taxes could be collected food security could be easily financed the jhollawallas feel.

But this number is a huge overestimation given that a lot of revenue foregone is difficult to capture. As Amartya Sen, the big inspiration for the jhollawallasput it in a column in The Hindu in January 2012 “This is, of course, a big overestimation of revenue that can be actually obtained (or saved), since many of the revenues allegedly forgone would be difficult to capture — and so I am not accepting that rosy evaluation.”

Also, it is worth remembering something that finance minister P Chidambaram pointed out in his budget speech. “There are 42,800 persons – let me repeat, only 42,800 persons – who admitted to a taxable income exceeding Rs 1 crore per year,” Chidambaram said.

So Indians do not like to pay tax. And just because a tax is implemented does not mean that they will pay up. This is an after effect of marginal income tax rates touching a high of 97% during the rule of Indira Gandhi. A huge amount of the economy has since moved to black, where transactions happen but are never recorded.To conclude, the basic point is that food security will turn out to be a fairly expensive proposition for India. But then Sonia Gandhi believes in it and so do other parties which have voted for it.

With this Congress has firmly gone back to the garibi hatao politics of Indira Gandhi. And that is not surprising given the huge influence Indira Gandhi has had on Sonia.

As Tavleen Singh puts it in Durbar “When she (i.e. Sonia) refused to become Congress president on the night Rajiv died, it was probably because she knew that if she took the job, she would be quickly exposed. In her year of semi-retirement she learned to speak Hindi well enough to read out a speech written in Roman script, and studied carefully the politics of her mother-in-law. There were rumours that she watched videos of the late prime minister Indira Gandhi so she could learn to imitate her mannerisms.”

Other than imitating the mannerisms of Indira Gandhi, Sonia has also ended up imitating her politics and her economics. Now only if Lal Bahadur Shastri had lived a few years more…

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 27, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

How the govt itself stoked the fires of food inflation

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

Hindi film songs have words of wisdom for almost all facets of life. Even inflation.

As the lines from a song in the 1974 superhit Roti, Kapda aur Makan go “Baaki jo bacha mehangai maar gayi(Of whatever was left inflation killed us).”

Inflation or the rise in prices of goods and services has been killing Indians over the last few years. What has hurt the common man even more is food inflation. Food prices have risen at a much faster pace than overall prices.

A discussion paper titled Taming Food Inflation in India released by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices(CACP), Ministry of Agriculture, on April 1, 2013, points out to the same. “Food inflation in India has been a major challenge to policy makers, more so during recent years when it has averaged 10% during 2008-09 to December 2012. Given that an average household in India still spends almost half of its expenditure on food, and poor around 60 percent (NSSO, 2011), and that poor cannot easily hedge against inflation, high food inflation inflicts a strong ‘hidden tax’ on the poor…In the last five years, post 2008, food inflation contributed to over 41% to the overall inflation in the country,” write the authors Ashok Gulati and Shweta Saini. Gulati is the Chairman of the Commission and Saini is an independent researcher.

During the period 2008-2009 to December 2012, the wholesale price inflation, a measure of the overall rise in prices, averaged at 7.4%. In the same period the food inflation averaged at 10.13% per year.

So who is responsible for food inflation, which is now close to 11%? The short answer is the government. As Gulati and Saini write “The Economist in its February 2013 issue highlights that it was the increased borrowings by the Indian government which fuelled inflation…It categorically puts the responsibility on the government for having launched a pre-election spending spree in 2008, which continued even thereafter.”

Gulati and Saini build an econometric model which helps them conclude that “fiscal Deficit, rising farm wages, and transmission of the global food inflation; together they explain 98 percent of the variations in Indian food inflation over the period 1995-96 to December, 2012…These empirical results clearly indicate that it would not be incorrect to blame the ballooning fiscal deficit of the country today to be the prime reason for the stickiness in food inflation.”

Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends. In the Indian context, it has been growing in the last few years as the government has been spending substantially more than what it has been earning.

The fiscal deficit of the Indian government in 2007-2008 (the period between April 1, 2007 and March 31, 2008) stood at Rs 1,26,912 crore. This jumped by 230% to Rs 4,18,482 crore, in 2009-2010 (the period between April 1, 2009 and March 31, 2010). This was primarily because the expenditure of the Congress led UPA government went up at a much faster pace than the income.

The government of India had a total expenditure of Rs 7,12,671 crore, during the course of 2007-2008. This grew by nearly 44% to Rs 10,24,487 crore in 2009-2010. The income of the government went up at a substantially slower pace. Between 2007-2008 and 2009-2010, the revenue receipts (the income that the government hopes to earn every year) of the government grew by a minuscule 5.7% to Rs 5,72,811 crore.

And it is this increased expenditure(reflected in the burgeoning fiscal deficit) of the government that has led to inflation. As Gulati and Saini point out “Indian fiscal package largely comprised of boosting consumption through outright doles (like farm loan waivers) or liberal increases in pay to organised workers under Sixth Pay Commission and expanded MGNREGA(Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act expenditures for rural workers. All this resulted in quickly boosting demand.”

So the increased expenditure of the government was on giving out doles rather than building infrastructure.

This meant that the money that landed up in the pockets of citizens was ready to be spent and was spent, sooner rather than later. “But with several supply bottlenecks in place, particularly power, water, roads and railways, etc, very soon, ‘too much money was chasing too few goods’. And no wonder, higher inflation in general and food inflation in particular, was a natural outcome,” write the authors.

So increased expenditure of the government led to increasing demand for goods and services. This increase in demand was primarily responsible for the economy growing by 8.6% in 2009-2010 and 9.3% in 2010-2011(the period between April 1, 2010 and March 31, 2011). But the increase in demand wasn’t met by an increase in supply, simply because India did not have the infrastructure required for increasing the supply of goods and services. And this led to too much money chasing too few goods.

No wonder this sent food prices spiralling. Food prices have continued to rise as the government expenditure has continued to go up. Also food prices have risen at a much faster pace than overall prices. This is primarily because agricultural prices respond much more to an increase in money supply vis a vis manufactured goods where prices tend to be stickier due to some prevalence of long term contracts. As Gulati and Saini put it “In fact, our analysis for the studied period shows that one percent increase in fiscal deficit increases money supply by more than 0.9 percent.”

The other major reason for a rising food prices is the rising cost of food production due to rising farm wages. This pushes inflation at two levels. First is the fact that an increase in farm wages drives up farm costs and that in turn pushes up prices of agricultural products. As the authors point out “During 2007-08 to 2011-12, nominal wages increased at much faster rate, by close to 17.5% per annum…The immediate impact of these increased farm wages is to drive-up the farm costs and thus push-up the farm prices, be it through the channel of MSP(minimum support price) or market forces.”

Rising farm wages also lead to a section of population eating better and which in turn pushes up price of protein food. As Gulati and Saini point out “This study finds that the pressure on prices is more on protein foods (pulses, milk and milk products, eggs, fish and meat) as well as fruits and vegetables, than on cereals and edible oils, especially during 2004-05 to December 2012. This normally happens with rising incomes, when people switch from cereal based diets to more protein based diets.”

In the recent past price of cereals like rice and wheat has also gone up substantially. This is primarily because the government is hoarding onto much more rice and wheat than it requires to distribute under its various social programmes.

If food inflation has to come down, the government has to control expenditure. The authors Gulati and Saini suggest several ways of doing it. The government can hope to earn Rs 80,000-100,000 crore if it can get around to selling the excessive grain stocks that it has. Other than help control its fiscal deficit, the government can also hope to control the price of cereals like rice and wheat which have been going up at a very fast rate by increasing their supply in the open market.

As the authors write “By liquidating(i.e selling) excessive grain stocks in the domestic market or through exports, massive savings of non-productive expenditures can be realized. For example, as against a buffer stock norm of 32 million tonnes of grains, India had 80 million tonnes of grains on July 1, 2012, and this may cross 90 million tonnes in July 2013. Even if one wants to keep 40 million tonnes of reserves in July, liquidating the remaining 50 million tonnes can bring approximately Rs 80,000-100,000 crore back to the exchequer. And with this much grain in the market food inflation will certainly come down. Else, the very cost of carrying this “extra” grain stocks alone will be more than Rs 10,000 crore each year, counting only their interest and storage costs.”

Of course this has its own challenges. More than half of this inventory of grain in India is concentrated in the states of Punjab and Haryana. Moving this inventory from Punjab and Haryana to other parts of the country will not be easy, assuming that the government opts to work on this suggestion. At the same time the government will have to do it in a way so as to ensure that the market prices of rice and wheat don’t collapse. And that is easier said than done.

The authors also recommend that the government can cut down on food and fertiliser subsidy by directly distributing it. “By going through cash transfers route (using Aadhar), one can plug in leakages in PDS(public distribution system) which, as per CACP calculations are around 40%, and save on high costs of storage and movement too, saving in all about Rs 40,000 crore on food subsidy bill,” write Gulati and Saini.

Something similar can be done on the fertiliser front as well. “Fertiliser subsidy, if given directly to farmers on per hectare basis (Rs 4000/ha to all small and marginal farmers which account for about 85 percent of farmers; and somewhat less (Rs 3500 and Rs 3000/ha) as one goes to medium and large farmers, and deregulating the fertiliser sector can bring in large savings of about Rs 20,000 crore along with greater efficiency in production and consumption of fertilisers.”

Whether the government takes these recommendations of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices seriously, remains to be seen. Meanwhile here is another brilliant Hindi film song from the 2010 hit Peepli Live: “Sakhi saiyan khoobai kaamat hain, mehangai dayan khaye jaat hai(O friend, my beloved earns a lot, but the inflation demon keeps eating us up).”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on April 2, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

UPA-nomics: How to hoard grain and let food prices soar

Vivek Kaul

Over the last few days my mother and her sister have been complaining about how the price of the 10 kg bag of rice that they buy has gone up by 17% in just over a couple of month’s time.

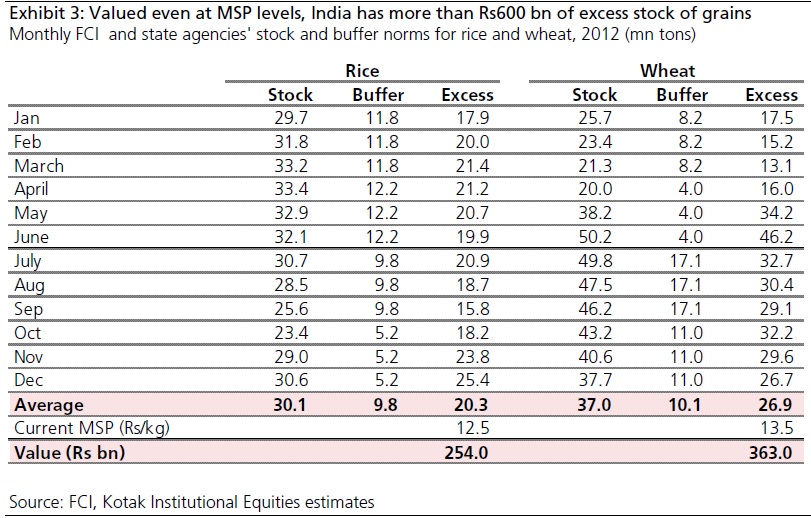

Now contrast this with what Akhilesh Tilotia of Kotak Institutional Equities Research writes in the GameChanger Perspectives report titled Putting the mountain of grains to use (Released on March 5, 2013). “India can raise more than Rs60,000 crore if it prunes its inventory of food grains: an excess 20 million tons of rice and 26 million tons of wheat (without accounting for procurements to be made this year),” writes Tilotia. (The table shows the numbers in detail).

As the above table shows the government currently has an excess rice stock worth around Rs 25,400 crore and an excess wheat stock worth Rs 36,300 crore, or more than Rs 60,000 crore in total. These numbers have been arrived at by taking into account the MSP of rice at Rs 12.5 per kg and the MSP of wheat at Rs 13.5 per kg and multiplying them with the excess stocks. What the table also tells us is that the government currently has an excess rice stock of nearly 2 times the buffer and an excess wheat stock of nearly 2.7 times the buffer.

The government sets a minimum support price(MSP) for wheat and rice. Every year the Food Corporation of India (FCI), or a state agency acting on its behalf, purchases rice and wheat at MSPs set by the government. The “supposed” idea behind setting the MSP much and that too much in advance is to give the farmer some idea of how much he should expect to earn when he sells his produce a few months later. FCI typically purchases around 15-20 percent of India’s wheat output and 12-15 percent of its rice output, estimates suggest.

At least this is how things are supposed to work in theory. But most government motives have unintended consequences. With an assured price more rice and wheat lands up with the government than it distributes through the public distribution system. Also with FCI obligated to purchase what the farmers bring in, its godowns overflow and at times the wheat and rice are dumped in the open, leading to rodents feasting on the crop.

On the other hand the way things currently are it helps the farmer as he has an assured buyer in the government for his produce. But what it also does is it pushes up prices of rice and wheat everywhere else, as more of it lands up in the godowns of FCI and not in the open market.

The procurement also adds to the food subsidy. The government pays for all the rice and wheat that the farmer brings to it and then lets a lot of it rot. The government currently has nearly 67 million tonnes of rice and wheat in stock. Of this nearly 47 million tonnes is excess.

Tilotia expects the rice and wheat stock of the government to go up to 100 million tonnes by the time this harvest season gets over. As he writes “After the current harvest season, Indian granaries will stock about 100 million tonnes of wheat and rice…A high inventory comes with a heavy carrying cost, which the FCI estimates at Rs6.12 per kg for year-end September 2014: At 100 million tons, this will cost India Rs 60,000 crore a year (forming most of its food subsidy bill).”

A higher food subsidy bill adds to the fiscal deficit and which as writers Firstpost regularly keeps discussing has huge consequences of its own. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government spends and what it earns.

In fact, the United States of America had a similar policy in place in the aftermath of The Great Depression which started in 1929, on a number of agri-commodities like wheat, tobacco, cotton etc. The government offered a support price to farmers. This support price had unintended consequences over the years, especially in case of wheat.

As Bruce Gardner writes in the research paper “The Political Economy of U.S.Export Subsidies for Wheat” (quoted by Tilotia) “The traditional means of price support is a governmental agreement, through its Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC), to buy wheat at the support price. This programme periodically led to governmental acquisition of large stocks which were costly to store and for which markets did not exist at the support price level.”

As is happening in India right now the American government ended up buying more and more wheat, of which it had no use for, especially at the price it was paying for it. The farmers had an assured buyer in the government and they went around producing more wheat than before.

This resulted in excess stocks with the American government. Over the years this excess wheat was exported at a subsidised rates. As Gardner writes “The subsidy ranged from 5 to 30 percent of the price of wheat, depending on world and U.S. market conditions in each year.” A lot of wheat was also donated under the Agricultural Trade and Development Act of 1954 ( better known as P.L. 480) of which India was a huge beneficiary in the late 50s and early 60s till Lal Bahadur Shastri initiated the agricultural revolution.

Gradually the wheat acreage, or the area over which wheat was planted, was also reduced in the United States. This meant that the farmers had to keep their land idle and not plant wheat on it. “Acreage allotments…were reintroduced in 1954 and reduced planted acreage by about 18 million acres (from 79 million in 1953 to an average of 61 million in 1954-56). Each producer had to stay under the farm’s allotment in order to be eligible for price support loans. In 1956 the Soil Bank program was introduced. It paid wheat growers about $20 per acre (roughly market rental rates) to idle an average of 12 million more acres (20 percent of preprogram acreage) in 1956-58,” writes Gardner.

India seems to be heading on the same path if the current policies don’t change. As Tilotia writes “India’s inventory is concentrated in the north-western states of Punjab and Haryana, which store 36 million tons of its 66 million tons of stock. Given the large procurement expected from these states again this year (though Madhya Pradesh may better Haryana in wheat procurement this year, especially given state elections), this imbalance can worsen.”

Interestingly, the government can use this excess inventory of rice and wheat to control inflation and at the same time bring down its fiscal deficit. The government currently has rice and wheat worth in excess of Rs 60,000 crore. On the other hand it also has a disinvestment target of Rs 54,000 crore for the next financial year (i.e. the period between April 1, 2013 and March 31, 2014). The government hopes to earn this amount by selling stakes it holds in public sector units to the public.

Along similar lines the government can try selling the excess rice and wheat that it currently holds in the open market. This will help control food inflation with the excess government stock hitting the market. Food forms around 43% of the consumer price inflation number and so if food inflation comes down, the consumer price inflation is also likely to come down.

The challenge of course in doing this is two fold. The first being moving grains from Punjab, Haryana where more than half the inventory lies. The second is to ensure that the market prices of rice and wheat don’t collapse.

Also the current MSP system is not working. If the idea is to pay the citizens of this country to improve their living standards, the government may be better off paying them in cash, rather than paying them in this roundabout manner that creates inflation. This is simply because the current system drives up the price of food for everyone else and it doesn’t necessarily always benefit the farmers. The middleman continue to make the most money.

As Tilotia puts it “If such a payment indeed needs to be made, there is no point in raising prices for all in the system by adding it to the price of the grain: Simply pay the farmer whatever support you want to pay him/her. India is reaching a situation where, by using UID it would be able to send payments to farmers directly. Maybe it is time to re-couple wheat and rice prices with global prices – that can meaningfully reduce inflation in India.”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on March 6,2013.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)