Even if you are the kind who avoids reading business as well as economic news, you can’t avoid coming across the term GDP or Gross Domestic Product, time and again. If the GDP goes up at a fast rate, the economy is doing well. If the GDP doesn’t go up as fast as it is expected to, the economy is not doing well. And if the GDP contracts or falls, then god help us!

At least this is how the mass media talks about the GDP.

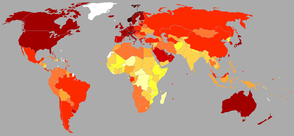

But what is the GDP? John Lanchester defines the term in How to Speak Money as: “The measure of all the goods and services produced inside a country.” It is a sort of a measure of the economic size of any country. Changes in GDP measure economic activity.

The trouble is that, at the end of the day it is a theoretical construct and there are problems with it. As Lanchester writes: “Many good things don’t contribute to GDP and many bad things do. The famous-to-economists example is divorce: when people get divorced they pay lots of lawyers’ fees. This adds nothing to anybody’s happiness except the lawyers’, but it adds plenty to the GDP.”

Then there is the problem of how to go about measuring the services part of any economy. As Diane Coyle writes in GDP—A Brief but Affectionate History: “The main input in a services business is the time spent by the employees on their job. What is the output of a teacher, though? Number of children processed through school? The average grade they attain on leaving? The highest subsequent qualification the children attain on average, or perhaps their lifetime earnings?”

Of course, these are not easy questions to answer. Then there are many other things that the GDP overlooks. As Rutger Bregman writes in Utopia for Realists: “Community service, clean air, free refills on the house – none of these things make the GDP an iota bigger. If a businesswoman marries her cleaner, the GDP dips when her hubby trades his job for unpaid work.”

The point being that GDP does not take into account unpaid work. As Bregman writes: “Or take Wikipedia. Supported by investments of time rather money, it has left the old Encyclopaedia Britannica in the dust – and taken the GDP down a few notches in the process.”

A lot of other unpaid work from cooking to babysitting to breast feeding children, which form a major part of daily lives, goes unmeasured as well. One reason for this might lie in the fact that a lot of the free unpaid work is carried out by women. As Coyle writes: “Generally official statistical agencies have never bothered – perhaps because it has been carried out mainly by women.”

Further, GDP does a very bad job of measuring advances in knowledge and technology. As Bregman writes: “Our computers, cameras and phones are all smarter, speedier and snazzier than ever, but also cheaper, and therefore they scarcely figure. Where we still had to shell out $300,000 for a single storage gigabyte 30 years ago, today it costs less than a dime.” Also, free products like Skype, which make our lives a tad easier, lead the GDP to contract.

Also, it is worth remembering that any sort of destruction adds to the GDP. As Lanchester writes: “Your house has just burnt down, and you’ve lost everything. That’s too bad; on the other hand, it’s great for GDP, because you’re going to have to rebuild it and re-buy all your stuff.”

This is precisely what happened to Japan after the Sendai seaquake in March, 2011. The total damage estimated by the World Bank was estimated to be around $235 billion. Nevertheless, things soon started to improve.

As Bregman writes: “After a slight dip in 2011, the following year saw the country’s economy grow 2%, and figures for 2013 were even better. Japan was experiencing the effects of an enduring economic law which holds that every disaster has a silver lining – at least for the GDP.”

The point being, there is a lot more to the GDP, than the media talks about.

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He can be reached at [email protected])

The column originally appeared in the Bangalore Mirror on May 11, 2016