On May 29, 2015, the ministry of statistics and programme implementation declared the gross domestic product (GDP) growth numbers for the last financial year 2014-2015, as well as the period between January and March 2015. The GDP is a measure of the size of an economy, and the GDP growth is essentially a measure of economic growth.

The GDP growth for 2014-2015 came in at 7.3%, whereas the GDP growth between January and March 2015 stood at 7.5%. The trouble is that these numbers which are theoretical constructs don’t seem believable once we start looking at real economic numbers.

Bank lending remains subdued. So do car sales. Corporate profitability is at a one decade low. And exports are stagnant. Capacity utilization continues to remain bad. And so does investment. In fact, the Reserve Bank of India governor, Raghuram Rajan even said the following, in an interaction he recently had with the media: “In the eyes of the rest of the world, it is a discrepancy why we feel the need for rate cuts when the economy is growing at 7.5%. Most economies growing at 7-7.5% are just going gang-busters and the issue there would be to restrain rather than accelerate growth.”

It seems that the Indian GDP number may have become a victim of what economists call the “survivor bias”. Before I get into explaining this bias some background information is necessary. In late January earlier this year, the ministry of statistics and programme implementation released a new method to calculate the GDP.

In the old method of calculating the GDP one of the key sources of information about the private sector was the RBI Study on company finances, which took into account financial results of around 2500 companies. The new GDP series uses the database of ministry of corporate affairs (MCA).

As Deep N Mukherjee of India Ratings recently wrote in a column on Firstpost: “The new series justifiably attempts to increase the coverage of the corporate sector and has used the MCA21 database maintained by the ministry of corporate affairs. Approximately 14 lakh companies are registered with MCA, of which 9.8 lakh companies are active. Post filtering for data availability, 5 lakh companies have been analysed and used for GDP estimation for 2011-12 and 2012-13.”

On the face of it, this sounds like a good thing to do. The trouble is that since 2013-2014, the number of companies on the database has come down to 3 lakhs.

“This is an outcome of companies not reporting possibly because they are closing down their operations. Thus, if out of 5 lakh companies 2 lakh have not reported, it should normally set alarm bells ringing about the economy. How the current methodology addresses this ‘survivor bias’ in the data is not clear,” writes Mukherjee.

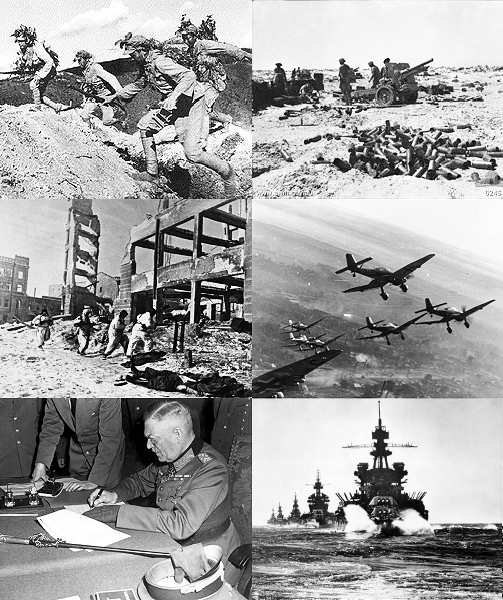

And what is survivor bias? Let me recount a story from the Second World War in order to explain this. During the Second World War, the British Royal Air Force (RAF) wanted to protect its planes from the German anti-aircraft guns and fighter planes. In order to do that it wanted to attach heavy plating to its airplanes.

The trouble was that the plates that were to be attached were heavy and hence, they had to be strategically attached at points where bullets from the Germans were most likely to hit.

An analysis revealed that the bullets were hitting a certain part of the plane more than the other parts. As Jordan Ellenberg writes in How Not to Be Wrong: The Hidden Maths of Everyday Life: “The damage[of the bullets] wasn’t uniformly distributed across the aircraft. There were more bullet holes in the fuselage, not so many in the engines.”

This essentially suggested that the area around the fuselage was getting hit the most by bullets and that is the area that had to be plated. Nevertheless, the German bullets should also have been also hitting the engine because the engine “is a point of total vulnerability”.

A statistician named Abraham Wald realised that things were not as straight forward as they seemed. As Ellenberg writes: ‘The armour, said Wald, doesn’t go where bullet holes are. It goes where bullet holes aren’t: on the engines. Wald’s insight was simply to ask: where are the missing holes? The ones that would have been all over the engine casing, if the damage had been spread equally all over the plane. The missing bullet holes were on the missing planes. The reason planes were coming back with fewer hits to the engine is that planes that got hit in the engine weren’t coming back.” They simply crashed.

As Gary Smith writes in Standard Deviations: Flawed Assumptions Tortured Data and Other Ways to Lie With Statistics: “Wald…had the insight to recognize that these data suffered from survivor bias…Instead of reinforcing the locations with the most holes, they should reinforce the locations with no holes.”Wald’s recommendations were implemented and ended up saving many planes which would have otherwise gone down.

Interestingly, survivor bias is a part of lot of other data as well and leads to wrong analysis at times. Take the data for judging the performance of mutual funds over a long period of time. The numbers typically end up overstating the returns earned primarily because something’s missing. As Ellenberg writes: “The funds that aren’t. Mutual funds don’t live forever. Some flourish, some die. The ones that die are, by and large, the ones that don’t make money. So judging a decade’s worth of mutual funds by the ones that still exist at the end of ten years is like judging our pilot’s evasive manoeuvres by counting the bullet holes in the planes that come back.” Hence, it makes sense to be sceptical about any mutual fund study that shows high returns. The first question you should be asking is whether the study has taken the performance of dead funds into account or not.

Now how is this linked to the Indian GDP? It is possible that the data being used to calculate the Indian GDP is not taking into account the fact that out of the five lakh companies on the MCA database around two lakh companies have not reported their numbers and may have possibly been shutdown. And if that is the case the corporate growth numbers are possibly being overstated and in the process pushing up the overall GDP number as well.

The economists need to be able to crack this puzzle and tell us the real story.

The column originally appeared on The Daily Reckoning on June 10, 2015