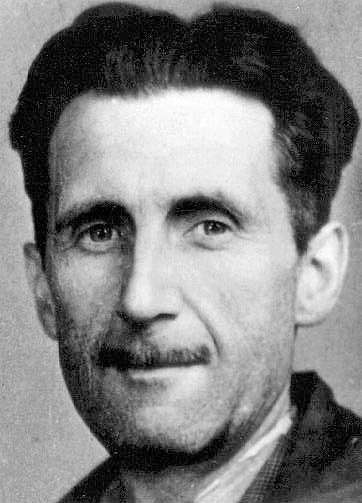

The Motihari born George Orwell wrote a lot of sensible things during his lifetime. One of them was a book called Animal Farm. My favourite sentence in the book is: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others”.

More than a sentence this is a phenomenon which is visible at various points of time in the society that we live in. Currently this phenomenon is at play at the State Bank of India(SBI), which has made a decision to e-auction 350 repossessed residential and commercial properties amounting to a total of Rs 1,000-Rs 1,200 crore.

The repossessed properties had been pledged as collateral for housing and other business loans taken from SBI. Reuters reports that “many of” these properties “were put up as collateral by fledgling entrepreneurs.” They were taken over by SBI under the the Security and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest (Sarfaesi) Act for non payment of dues.

“The SBI auction will be the biggest nationwide online sale to date,” Reuters reports. “We are now a lot more aggressive,” Parveen Kumar Malhotra, a deputy managing director at SBI, who leads a special unit managing stressed assets, told Reuters.

Commercially this makes immense sense and SBI should have been aggressive about defaults from day one. A bank is not in the business of losing money it lends out. It has a certain responsibility towards depositors whose money it is lending out. It needs to ensure that returns are generated on this money that is loaned to those who need it.

Nevertheless, India’s largest bank has not shown the same aggression when it comes to recovering money from big defaulters. In that sense the entire thing is very Orwellian—all animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.

As of December 31, 2014, the gross non-performing assets (NPAs) of the State Bank of India stood at Rs 61,991 crore or 4.9% of the total loans given by the bank. Of these gross NPAs of large and mid-corporates accounted for Rs 27,504 crore. The large corporates accounted for Rs 1,074 crore whereas the mid-corporates accounted for Rs 26,430 crore of bad loans.

The gross NPAs accounted for by large corporates has fallen from Rs 3,658 crore to Rs 1,074 crore between December 2013 and December 2014. On the other hand gross NPAs accounted for by mid-corporates grew from Rs 26,191 crore to Rs 26,430 crore, during the same period.

Gross NPAs from retail loans fell from Rs 4,103 crore to Rs 3,082 crore. Gross NPAs accounted for by small and medium enterprises fell from Rs 17,382 crore to Rs 16,427 crore. In fact, the gross NPAs accounted for by agriculture and international lending have also fallen between December 2013 and December 2014. Interestingly, the gross NPAs of every form of lending other than lending to mid-corporates has come down, data from the bank shows.

What this tells us very clearly is that the bank has been going aggressively after all forms of bad loans. The total gross NPAs have come down from Rs 67,799 crore or 5.73% of total loans to Rs 61,991 crore or 4.9% of total loans. But SBI hasn’t shown the same aggression when it comes to recovering loans from mid-corporates. Why is such special treatment being given out to corporates?

This is something that the Reserve Bank of India governor Raghuram Rajan had clearly pointed out in a speech he made in November last year. As Rajan said, India is “a country where we have many sick companies but no “sick” promoters.” “In India, too many large borrowers insist on their divine right to stay in control despite their unwillingness to put in new money. The firm and its many workers, as well as past bank loans, are the hostages in this game of chicken — the promoter threatens to run the enterprise into the ground unless the government, banks, and regulators make the concessions that are necessary to keep it alive. And if the enterprise regains health, the promoter retains all the upside, forgetting the help he got from the government or the banks – after all, banks should be happy they got some of their money back!”

And since banks can’t and don’t do much about corporate loans that have gone bad, they go with all guns blazing to recover loans from their smaller defaulters. As Rajan put it “The SARFAESI (Securitization and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interests) Act of 2002 is, by the standards of most countries, very pro-creditor as it is written. This was probably an attempt by legislators to reduce the burden on debt-recovery tribunals and force promoters to pay. But its full force is felt by the small entrepreneur who does not have the wherewithal to hire expensive lawyers or move the courts, even while the influential promoter once again escapes its rigour. The small entrepreneur’s assets are repossessed quickly and sold, extinguishing many a promising business that could do with a little support from bankers.”

This is precisely how SBI’s decision to auction 350 residential and commercial properties in order to recover bad loans is playing out. And George Orwell saw it coming.

The column originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on Mar 16, 2015

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)