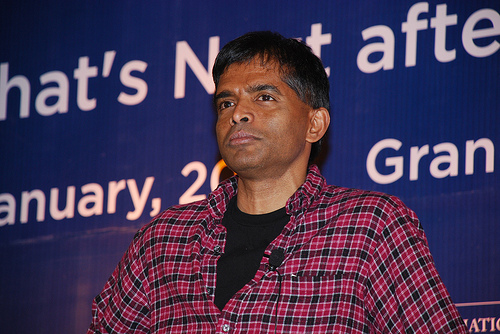

Vivek Kaul

A few years back I had booked a ticket on an early morning Kingfisher flight from Mumbai to Ranchi, or so I had thought. I came to realize I was on Kingfisher Red and not the full service Kingfisher only once I was inside the aircraft.

Sometime later I came to realize that several people I knew had had a similar experience. They had booked flights thinking they were on the Kingfisher full service, only to realize later that they were on Kingfisher Red.

The airline clarified that it was not their mistake but the mistake of the websites that did not make a distinction between Kingfisher Red and Kingfisher First.

But the question that cropped up in my mind was that why would Kingfisher, a premium-upmarket brand, want to dilute its positioning by associating itself with Kingfisher Red, which was essentially a low-cost airline.

Vijay Mallya, started Kingfisher Airlines in 2005. A few years later he tried to get into the low cost airline business, which was the flavour of the season back then, by taking over Deccan Aviation which ran Air Deccan, a low cost airline. He rebranded it as Kingfisher Red. By doing this he diluted the premier positioning that Kingfisher Airlines had acquired in the minds of the consumer.

To explain this a little differently, let us take the example of Hindustan Unilever Ltd (HUL). It sells the Lifebuoy which is targeted at the lower end of the market and goes with the line tandurusti ki raksha karta hai Lifebuoy. The company also sells Lux which is targeted at the upper end of the market and comes with the tagline filmi sitaron ka saundarya sabun.

Of course, the positioning of Lifebuoy and Lux is totally different. And HUL tries to make this very very clear in the minds of the consumer. First of all, both the products have different names. Second the pricing is very different. And third, the advertisements of both the products emphasize on the “different” positioning over and over again.

Now Mallya running a low cost airline under the premium brand name of Kingfisher would be like HUL selling Lux soap under the name of Lifebuoy premium.

And it’s not just about the brand name and the positioning in the mind of the consumer. The philosophy required to run a premium brand is totally different in comparison to the philosophy required to run a low cost brand. Hence, Mallya buying Air Deccan was mistake. And then changing its name to Kingfisher Red was an even bigger mistake.

So in the end this did not work and Mallya decided to close down Kingfisher Red. He explained it by saying that “We are doing away with Kingfisher Red, we do not want to compete in the low-cost segment. We cannot continue to fly and make losses, but we have to be judicious to give choice to our customers.”

Kingfisher might have just survived if it had not made the mistake of buying Kingfisher Red. World-over several airlines have tried running a full-service and a low cost airline at the same time and made a mess of it. A company cannot run a low cost airline and a full service career at the same time. The basic philosophy required in running these two kind of careers is completely different from one another.

But the bigger question is what was Vijay Mallya trying to do by running a liquor business, a real estate business and an airline at the same time? This was other than spending substantial time on his expensive hobbies of trying to run a cricket and an FI team, and cheaper ones like commenting regularly on Twitter.

There isn’t really any link among the businesses Mallya runs. Some people have tried to explain that the airline was just surrogate advertising for the beer of the same name. But then there are cheaper ways of advertising than running an airline and losing thousands of crores doing it.

Businesses over the years have become more complicated. And just because a company has been good at one particular business doesn’t mean it will be good at another totally unrelated business.

Mallya is not the only one realizing this basic fact. The period between 2002 and 2008 was an era of easy money. Businesses could borrow money very easily to expand as well as get into new business. And this is what finally got businessmen like Mallya into trouble.

The British economist John Kay calls this the new Peter’s Principle. The original Peter’s Principle essentially states that every person rises to his or her level of incompetence in a hierarchy. Simply put, as a person keeps getting promoted he is bound to appointed to a job, he is not good at. The same is the case with companies which keep buying and diversifying into different businesses, until they land up in a business they don’t really understand. And that drives them down.

Mallya was a victim of the new Peter’s Principle, his non related diversification into the airline business cost him dearly. The lack of focus has hurt Mallya’s core alcohol business as well and United Spirits is no longer India’s most profitable alcohol company. That tag now belongs to the Indian division of the French giant Pernod Ricard.

An era of easy money got Indian entrepreneurs including Mallya to get into all kinds of things which they did not understand and had no clue about. Kishore Biyani brought the retail revolution to India, having been inspired by Sam Walton who started Wal-Mart. His retail businesses were doing decently well till he decided to get into a wide variety of businesses from launching an insurance company to even selling mobile phone connections. When times were good he accumulated a lot of debt in trying to grow fast. Now he is in trouble in trying to service the debt and rumors are flying thick and fast that he is planning to sell Big Bazaar, his equivalent of Wal-Mart. This after he sold controlling stake in the cloths retailer, Pantaloons.

Let’s take the case of DLF, the biggest real estate company in the country. It tried getting into the insurance and mutual fund business. It had to sell its stake in the mutual fund business and if news reports are to be believed it is trying to lower its stake in the insurance venture. It also tried unsuccessfully to get into the luxury hotel business and failed. Hotel Leela tried to get into the up-market apartments space and failed.

Reliance Energy (the erstwhile BSES) was turned into Reliance Infra and now is into all kinds of things. It is building one section of the Mumbai Metro, the completion of which keeps getting postponed. It is also supposed to build the remaining portion of the sealink in Mumbai.

The days when businesses like Tata and Birla used to do everything under the sun are long over. In fact, those were the days of license quota raj with very little competition. Hence companies could get into a new space as long as they got a license for it.

An interesting example is that of the Ambassador. The car had the same engine as of the original Morris Oxford which was made in 1944. The same engine was a part of the Ambassador car sold in India till 1982. The technology did not change for nearly four decades.

Given this lack of change, the businessmen could focus on multiple businesses at the same time. That is not possible anymore with technology and consumer needs and wants changing at a very fast pace. Even focused companies like Nokia missed out on the smart phone revolution in India.

Look at the newer businesses some of the big-older companies have got into over the years. The retail business of Ambanis hasn’t gone anywhere. Same is true with that of the retail business of the Aditya Birla group. The telecom business of the Tatas has lost a lot of money over the years. Though, they finally seem to be getting it right.

Hence it’s becoming more and more essential for businesses to focus on what they know best. And when it comes to airlines its time Mallya read what Warren Buffett told his shareholders a few years back.

“Now let’s move to the gruesome. The worst sort of business is one that grows rapidly, requires significant capital to engender the growth, and then earns little or no money. Think airlines. Here a durable competitive advantage has proven elusive ever since the days of the Wright Brothers. Indeed, if a farsighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favor by shooting Orville down. The airline industry’s demand for capital ever since that first flight has been insatiable. Investors have poured money into a bottomless pit, attracted by growth when they should have been repelled by it. And I, to my shame, participated in this foolishness when I had Berkshire buy U.S. Air preferred stock in 1989. As the ink was drying on our check, the company went into a tailspin, and before long our preferred dividend was no longer being paid. But we then got very lucky. In one of the recurrent, but always misguided, bursts of optimism for airlines, we were actually able to sell our shares in 1998 for a hefty gain. In the decade following our sale, the company went bankrupt.”

The bigger sucker saved Buffett. But Mallya may not have any such luck

(The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on July 5,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/business/how-the-new-peter-principle-caused-kingfishers-downfall-368549.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

warren buffett

People should listen to market experts for entertainment, not elucidation.

Michael J. Mauboussin is Chief Investment Strategist at Legg Mason Capital Management in the United States. He is also the author of bestselling books on investing like Think Twice: Harnessing the Power of Counterintuition and More Than You Know: Finding Financial Wisdom in Unconventional Places. His latest book The Success Equation: Untangling Skill and Luck in Business, Sports, and Investing is due later this year. In this interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul on the various aspects of luck, skill and randomness and the impact they have on business, life and investing.

Excerpts:

How do you define luck?

The way I think about it, luck has three features. It happens to a person or organization; can be good or bad; and it is reasonable to believe that another outcome was possible. By this definition, if you win the lottery you are lucky, but if you are born to a wealthy family you are not lucky—because it is not reasonable to believe that any other outcome was possible—but rather fortunate.

How is randomness different from luck?

I like to distinguish, too, between randomness and luck. I like to think of randomness as something that works at a system level and luck on a lower level. So, for example, if you gather a large group of people and ask them to guess the results of five coin tosses, randomness tells you that some in the group will get them all correct. But if you get them all correct, you are lucky.

And what is skill?

For skill, the dictionary says the “ability to use one’s knowledge effectively and readily in execution or performance.” I think that’s a good definition. The key is that when there is little luck involved, skill can be honed through deliberate practice. When there’s an element of luck, skill is best considered as a process.

You have often spoken about the paradox of skill. What is that?

The paradox of skill says that as competitors in a field become more skillful, luck becomes more important in determining results. The key to this idea is what happens when skill improves in a field. There are two effects. First, the absolute level of ability rises. And second, the variance of ability declines.

Could you give us an example?

One famous example of this is batting average in the sport of baseball. Batting average is the ratio of hits to at-bats. It’s somewhat related to the same term in cricket. In 1941, a player named Ted Williams hit .406 for a season, a feat that no other player has been able to match in 70 years. The reason, it turns out, is not that no players today are as good as Williams was in his day—they are undoubtedly much better. The reason is that the variance in skill has gone down. Because the league draws from a deeper pool of talent, including great players from around the world, and because training techniques are vastly improved and more uniform, the difference between the best players and the average players within the pro ranks has narrowed. Even if you assume that luck hasn’t changed, the variance in batting averages should have come down. And that’s exactly what we see. The paradox of skill makes a very specific prediction. In realms where there is no luck, you should see absolute performance improve and relative performance shrink. That’s exactly what we see.

Any other example?

Take Olympic marathon times as an example. Men today run the race about 26 minutes faster than they did 80 years ago. But in 1932, the time difference between the man who won and the man who came in 20th was close to 40 minutes. Today that difference is well under 10 minutes.

What is the application to investing?

The application to investing is straightforward. As the market is filled with participants who are smart and have access to information and computing power, the variance of skill will decline. That means that stock price changes will be random—a random walk down Wall Street, as Burton Malkiel wrote—and those investors who beat the market can chalk up their success to luck. And the evidence shows that the variance in mutual fund returns has shrunk over the past 60 years, just as the paradox of skill would suggest. I want to be clear that I believe that differential skill in investing remains, and that I don’t believe that all results are from randomness. But there’s little doubt that markets are highly competitive and that the basic sketch of the paradox of skill applies.

How do you determine in the success of something be it a song, book or a business for that matter, how much of it is luck, how much of it is skill?

This is a fascinating question. In some fields, including sports and facets of business, we can answer that question reasonably well when the results are independent of one another. When the results depend on what happened before, the answer is much more complex because it’s very difficult to predict how events will unfold.

Could you explain through an example?

Let me try to give a concrete example with the popularity of music. A number of years ago, there was a wonderful experiment called MusicLab. The subjects thought the experiment was about musical taste, but it was really about understanding how hits happen. The subjects who came into the site saw 48 songs by unknown bands. They could listen to any song, rate it, and download it if they wanted to. Unbeknownst to the subjects, they were funneled into one of two conditions. Twenty percent went to the control condition, where they could listen, rate, and download but had no access to what anyone else did. This provided an objective measure of the quality of songs as social interaction was absent.

What about the other 80%?

The other 80 percent went into one of 8 social worlds. Initially, the conditions were the same as the control group, but in these cases the subjects could see what others before them had done. So social interaction was present, and by having eight social worlds the experiment effectively set up alternate universes. The results showed that social interaction had a huge influence on the outcomes. One song, for instance, was in the middle of the pack in the control condition, the #1 hit on one of the social worlds, and #40 in another social world. The researchers found that poorly rated songs in the control group rarely did well in the social worlds—failure was not hard to predict—but songs that were average or good had a wide range of outcomes. There was an inherent lack of predictability. I think I can make the statement ever more general: whenever you can assess a product or service across multiple dimensions, there is no objective way to say which is “best.”

What is the takeaway for investors?

The leap to investing is a small one. Investing, too, is an inherently social exercise. From time to time, investors get uniformly optimistic or pessimistic, pushing prices to extremes.

Was a book like Harry Potter inevitable as has often been suggested after the success of the book?

This is very related to our discussion before about hit songs. When what happens next depends on what happened before, which is often the case when social interaction is involved, predicting outcomes is inherently difficult. The MusicLab experiment, and even simpler simulations, indicate that Harry Potter’s success was not inevitable. This is very difficult to accept because now that we know that Harry Potter is wildly popular, we can conjure up many explanations for that success. But if you re-played the tape of the world, we would see a very different list of best sellers. The success of Harry Potter, or Star Wars, or the Mona Lisa, can best be explained as the result of a social process similar to any fad or fashion. In fact, one way to think about it is the process of disease spreading. Most diseases don’t spread widely because of a lack of interaction or virulence. But if the network is right and the interaction and virulence are sufficient, disease will propagate. The same is true for a product that is deemed successful through a social process.

And this applies to investing as well?

This applies to investing, too. Instead of considering how the popularity of Harry Potter, or an illness, spreads across a network you can think of investment ideas. Tops in markets are put in place when most investors are infected with bullishness, and bottoms are created by uniform bearishness. The common theme is the role of social process.

What about someone like Warren Buffett or for that matter Bill Miller were they just lucky, or was there a lot of skill as well?

Extreme success is, almost by definition, the combination of good skill and good luck. I think that applies to Buffett and Miller, and I think each man would concede as much. The important point is that neither skill nor luck, alone, is sufficient to launch anyone to the very top if it’s a field where luck helps shape outcomes. The problem is that our minds equate success with skill so we underestimate the role of randomness. This was one of Nassim Taleb’s points in Fooled by Randomness. All of that said, it is important to recognize that results in the short-term reflect a lot of randomness. Even skillful managers will slump, and unskillful managers will shine. But over the long haul, good process wins.

How do you explain the success of Facebook in lieu of the other social media sites like Orkut, Myspace, which did not survive?

Brian Arthur, an economist long affiliated with the Santa Fe Institute, likes to say, “of networks there shall be few.” His point is that there are battles for networks and standards, and predicting the winners from those battles is notoriously difficult. We saw a heated battle for search engines, including AltaVista, Yahoo, and Google. But the market tends to settle on one network, and the others drop to a very distant second. I’d say Facebook’s success is a combination of good skill, good timing, and good luck. I’d say the same for almost every successful company. The question is if we played the world over and over, would Facebook always be the obvious winner. I doubt that.

Would you say that when a CEO’s face is all over the newspapers and magazines like is the case with the CEO of Facebook , he has enjoyed good luck?

One of the most important business books ever written is The Halo Effect by Phil Rosenzweig. The idea is that when things are going well, we attribute that success to skill—there’s a halo effect. Conversely, when things are going poorly we attribute it to poor skill. This is often true for the same management of the same company over time. Rosenzweig offers Cisco as a specific example. So the answer is that great success, the kind that lands you on the covers of business magazines, almost always includes a very large dose of luck. And we’re not very good at parsing the sources of success.

You have also suggested that trying to understand the stock market by tuning into so called market experts is not the best way of understanding it. Why do you say that?

The best way to answer this is to argue that the stock market is a great example of a complex adaptive system. These systems have three features. First, they are made up of heterogeneous agents. In the stock market, these are investors with different information, analytical approaches, time horizons, etc. And these agents learn, which is why we call them adaptive. Second, the agents interact with one another, leading to a process called emergence. The interaction in the stock market is typically through an exchange. And, finally, we get a global system—the market itself.

So what’s the point you are trying to make?

Here’s a key point: There is no additivity in these systems. You can’t understand the whole simply by looking at the behaviors of the parts. Now this is in sharp contrast to other systems, where reductionism works. For example, an artisan could take apart my mechanical wristwatch and understand how each part contributes to the working of the watch. The same approach doesn’t work in complex adaptive systems.

Could you explain through an example?

Let me give you one of my favorite examples, that of an ant colony. If you study ants on the colony level, you’ll see that it’s robust, adaptive, follows a life cycle, etc. It’s arguably an organism on the colony level. But if you ask any individual ant what’s going on with the colony, they will have no clue. They operate solely with local information and local interaction. The behavior of the colony emerges from the interaction between the ants. Now it’s not hard to see that the stock market is similar. No individual has much of a clue of what’s going on at the market level. But this lack of understanding smacks right against our desire to have experts tell us what’s going on. The record of market forecasters has been studied, and the jury is in: they are very bad at it. So I recommend people listen to market experts for entertainment, not for elucidation.

How does the media influence investment decisions?

The media has a natural, and understandable, desire to find people who have views that are toward the extremes. Having someone on television explaining that this could happen, but then again it may be that, does not make for exciting viewing. Better is a market boomster, who says the market will skyrocket, or a market doomster, who sees the market plummeting.

Any example?

Phil Tetlock, a professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, has done the best work I know of on expert prediction. He has found that experts are poor predictors in the realms of economic and political outcomes. But he makes two additional points worth mentioning. The first is that he found that hedgehogs, those people who tend to know one big thing, are worse predictors than foxes, those who know a little about a lot of things. So, strongly held views that are unyielding tend not to make for quality predictions in complex realms. Second, he found that the more media mentions a pundit had, the worse his or her predictions. This makes sense in the context of what the media are trying to achieve—interesting viewing. So the people you hear and see the most in the media are among the worst predictors.

Why do most people make poor investment decisions? I say that because most investors aren’t able to earn even the market rate of return?

People make poor investment decisions because they are human. We all come with mental software that tends to encourage us to buy after results have been good and to sell after results have been poor. So we are wired to buy high and sell low instead of buy low and sell high. We see this starkly in the analysis of time-weighted versus dollar-weighted returns for funds. The time-weighted return, which is what is typically reported, is simply the return for the fund over time. The dollar-weighted return calculates the return on each of the dollars invested. These two calculations can yield very different results for the same fund.

Could you explain that in some detail?

Say, for example, a fund starts with $100 and goes up 20% in year 1. The next year, it loses 10%. So the $100 invested at the beginning is worth $108 after two years and the time-weighted return is 3.9%. Now let’s say we start with the same $100 and first year results of 20%. Investors see this very good result, and pour an additional $200 into the fund. Now it is running $320—the original $120 plus the $200 invested. The fund then goes down 10%, causing $32 of losses. So the fund will still have the same time-weighted return, 3.9%. But now the fund will be worth $288, which means that in the aggregate investors put in $300—the original $100 plus $200 after year one—and lost $12. So the fund has positive time-weighted returns but negative dollar-weighted returns. The proclivity to buy high and sell low means that investors earn, on average, a dollar-weighted return that is only about 60% of the market’s return. Bad timing is very costly.

What is reversion to the mean?

Reversion to the mean occurs when an extreme outcome is followed by an outcome that has an expected value closer to the average. Let’s say you are a student whose true skill suggests you should score 80% on a test. If you are particularly lucky one day, you might score 90%. How are you expected to do for your next test? Closer to 80%. You are expected to revert to your mean, which means that your good luck is not expected to persist. This is a huge topic in investing, for precisely the reason we just discussed. Investors, rather than constantly considering reversion to the mean, tend to extrapolate. Good results are expected to lead to more good results. This is at the core of the dichotomy between time-weighted and dollar-weighted returns. I should add quickly that this phenomenon is not unique to individual investors. Institutional investors, people who are trained to think of such things, fall into the same trap.

In one of your papers you talk about a guy who manages his and his wife’s money. With his wife’s money he is very cautious and listens to what the experts have to say. With his own money his puts it in some investments and forgets about it. As you put it, threw it in the coffee can. And forgot about it. It so turned out that the coffee can approach did better. Can you take us through that example?

This was a case, told by Robert Kirby at Capital Guardian, from the 1950s. The husband managed his wife’s fund and followed closely the advice from the investment firm. The firm had a research department and did their best to preserve, and build, capital. It turns out that unbeknownst to anyone, the man used $5,000 of his own money to invest in the firm’s buy recommendations. He never sold anything and never traded, he just plopped the securities into a proverbial coffee can(those were the days of paper). The husband died suddenly and the wife then came back to the investment firm to combine their accounts. Everyone was surprised to see that the husband’s account was a good deal larger than his wife’s. The neglected portfolio fared much better than the tended one. It turns out that a large part of the portfolio’s success was attributable to an investment in Xerox.

So what was the lesson drawn?

Kirby drew a more basic lesson from the experience. Sometimes doing nothing is better than doing something. In most businesses, there is some relationship between activity and results. The more active you are, the better your results. Investing is one field where this isn’t true. Sometimes, doing nothing is the best thing. As Warren Buffett has said, “Inactivity strikes us as intelligent behavior.” As I mentioned before, there is lots of evidence that the decisions to buy and sell by individuals and institutions does as much, if not more, harm than good. I’m not saying you should buy and hold forever, but I am saying that buying cheap and holding for a long time tends to do better than guessing what asset class or manager is hot.

(The interview was originally published in the Daily News and Analysis(DNA) on June 4,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/money/interview_people-should-listen-to-market-experts-for-entertainment-not-elucidation_1697709)

(Interviewer Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

‘I’ve never found a good pick by reading a news story’

Aswath Damodaran is one of the world’s premier experts in the field of equity valuation. He has written several books like Damodaran on Valuation, Investment Fables, The Dark Side of Valuation and most recently The Little Book of Valuation: How to Value a Company, Pick a Stock and Profit, on the subject. He is a Professor of Finance at the Stern School of Business at New York University where he teaches corporate finance and equity valuation. . In this interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul.

How did you get into the field of valuation?

I started in finance as a general area and then I got interested in valuation when I started teaching. Valuation is a piece of almost everything you do and I was surprised how ill developed it was as a field of thought. It was almost random and not much thinking had gone into thinking about how to do it systematically.

A lot of valuation is basically compound interest when you discount the expected cash flows. So how much of it is math and how much of it is art?

Much of it is not the compound interest or the discount factor it is really the cashflows you have to estimate. So most of it is actually is in the numerator. It is about figuring out what business you are in. Figuring out how you make money. Figuring out what the margins are. What the competition is going to be. So numerator is where all the action is and it is actually very little to do with mathematics. It is more an understanding of business and actually getting it into numbers.

Can you give us an example?

So if you are trying to value Facebook getting the discount rate for Facebook is trivial. It is easy. It is about 11.5%. It is about the 80th percentile in terms of riskiness of companies. The trouble with Facebook is figuring out, first what business they are going to be in, because they haven’t figured it out themselves. How are they going to convert a billion users into revenues and income? And second, if they even manage to do it, how much those revenues will be, what will the margins etc. And those are all functions where you cannot think just Facebook standing alone. It is going to compete against Google. It is going compete against Apple. It is going to compete against other social media companies. So you have to make judgement calls of how it is all going to play out. It is numbers but the numbers come from understanding business. Understanding strategy. Understanding competition. Understanding all the things that kind of come into play.

You just mentioned that the discounting rate for expected cash flows from Facebook was at 11.5%. How did you arrive at that?

I have the cost of capital for by every sector in the US.

So this is the cost of capital for dotcoms?

This is actually the cost of capital for risky technology capitals. So basically I am saying is that I could sit there and try to finesse it and say is it 11.8% or is it 11.2%. But it doesn’t really matter. Getting the revenues and margins is more critical than getting the discount rate narrowed down.

This 11.5% would be from a combination of equity and debt?

For a young growth company it is almost going to be all equity. You don’t borrow money if you are that small and when you are in a high growth phase it is not worth it. It is almost all equity.

I recently read a blog of yours where you said that you have sold Apple shares even though they were undervalued. Why did you do that?

There are two parts to the investment process. One is the value part to the process. And the other is the pricing part to the process. To make money you need to be comfortable with both parts. You want to feel comfortable with value and you have to feel comfortable that price is going to converge on the value. In the case of Apple for 15 years I was comfortable with my estimate of value and I was comfortable that the price would converge on value. In the last year the Apple stockholder base has had a fairly dramatic change. There has been influx of a lot of institutional investors who have coming in as herd investors and momentum investors who go wherever the price is hottest. You have also got a lot of dividend investors who came in last year because they expected Apple to start paying dividends.

What happened because of that?

So you got this influx of new investors with very different ideas of what they expect Apple to do in the future. They are all in there. And right now they are okay for the moment because Apple is able to keep them all reasonably happy. But I think this is a game where I have lost control of the pricing process because those investors turn on a dot. Like they did, when the stock went from $640 to $530 for no reason at all. You look at any news that came out. Nothing came out. So why is the stock worth $640 and eight weeks later $530? But that’s the nature of momentums stocks. It is not news that drives the price anymore, it’s the herd. Basically if it moves in one direction, prices are going to go up $20. If it moves in the other direction, it is going to go down $30. And I looked at the pricing process and said I have lost control of this part of the process. I am comfortable with the value still. But I am leaving not forever. If these guys keep pushing it down, sooner or later they are going to push it to a point where these guys leave and then I can step in buy the stock. So it’s not permanent but I think at the moment it has become a momentum stock.

You have talked about the danger of purely relying on stories while investing. But that’s how most investors invest. What are the problems with that?

Even momentum investors want a crutch. Basically stories give them a crutch. You have decided to buy the stock anyway because everyone else is doing it. You don’t want to tell people because that doesn’t sound good so you look for a story to convince yourself that you area really doing this for a good reason. The power of the story is very strong, I am not denying it. But I am saying that if there is a story my job is to bring it into the numbers and see if that story holds up to scrutiny.

Any example?

You can talk about user base. Facebook the story is that they have lots of users. My job is to take those billion users and talk about what that might mean in revenues and margins and operating income and cash flows. And not just say that there are lot of users therefore the company must be worth a lot. If a Chinese company says we are going to be valued. There are a billion Chinese. Okay. What does that mean? You have a billion Chinese but how much will be you able to sell? How much will they buy your product? So I think you need to get past the macro big story telling because it is easy to fall into saying that hey this company is worth a lot.

Can smaller investors make money by piggybacking on investment decisions of big investors?

If you look at institutional investors they do things so badly why do you want to piggyback on them.

Someone like a Warren Buffett and Rakesh Jhunjhunwala in the Indian context?

You could but I think by the time you get the information it is usually too late. It is not like you are the only one who finds out that Warren Buffett has bought a stock. Half the world has found out. So when you get to lineup to buy the stock, everyone else is buying the stock and price has already moved up.

George Soros once said that most money is made by entering a bubble early. What are your views on that?

Everybody is guilty of hyperbole when it comes to bubbles and Soros is no exception. Soros has never been a great micro investor. He has made his money on macro bets. He has always been. He has never been a great stock picker. For him it is got to be massive macro bubbles, an asset class that gets overpriced or underpriced. You’re right if you can call macro bubbles you can make a lot of money. John Paulson called the housing bubble made a few billion dollars. So he is right and he is wrong. He is right because if you can call a macro bubble you can make a lot of money. He is wrong because if you make your investment philosophy calling macro bubbles, you better get lucky, because everybody is calling macro bubbles and most of them are going to be wrong.

You have talked about buying the 35worst stocks in the market and holding that investment and making money on it. How does that work?

It’s called the classic contrarian investment strategy where you buy the biggest holders and you hold them for a long period. There is evidence that if you hold them for a long period that they tend to be the best investments. But it comes with caveats. One is that if you buy the 35 biggest losers they often tend to be low priced stocks because they have gone down so much which increases the transaction cost of your trading. The other is that it is very dependant on your time horizon. It turns out that if you buy the lowest price stocks for the first 18 months they actually underperform. It is only after that they turnaround. This means that if you buy these stocks you are going to get about 18 months of heart burn and stomach aches. And for many people they don’t have the patience to stay in. So they often buy the worst stocks after reading these studies. About 12 months in they lose patience they sell it. It is very dependant on both those pieces of puzzle falling in.

How much role does media play in influencing investment decisions of people?

Media and analysts are followers. None of the media told us last week that Facebook was going to collapse. Now of course everybody is talking about it. So basically when I see in the media news stories I see a reflection of what has already happened. It is a lagging indicator. It is not a leading indicator. I have never ever found a good investment by reading a news story. But I have heard about why an investment was good in hindsight by reading a news story about it.

I am not a great believer that I can find good investments in the media. That’s not their job anyway.

(The interview was originally published in the Daily News and Analysis(DNA) on June 2,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/money/interview_ive-never-found-a-good-pick-by-reading-a-news-story_1696935)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Facebook is a bubble and it will burst

Vivek Kaul

So let me be a killjoy this Monday morning and say that Facebook is a bubble. And like all bubbles it will burst.

The price of the Facebook share closed at $38.23 at the close of trading on Friday. At this price the company was worth around $104.6billion.The basic question that crops up here is that whether Facebook deserves such a high price? “It’s exceedingly dangerous to pay a $100 billion valuation for a company that hasn’t figured out a way to make money,” Aswath Damodaran, a professor at Stern Business School at New York University told Barrons Online. Damodaran is one of the world’s premier experts on valuation.

Facebook versus Google

Facebook earned 43 cents per share in 2011. At its Friday closing price of $38.23, the company has a price to earnings ratio of around 88.4 ($38.23/43cents). Now compare this to Google, which is the closest comparison we can make with a stock like Facebook. Google had an earnings per share of $33 in 2011. The market price of the company closed at $600.4 on Friday, implying a price to earnings ratio of 18.2 ($600.14/$33). This makes Facebook around five times as expensively priced as Google (88.4/18.2). Price to earnings ratio is equal to the latest market price of the share of the company divided by its earnings per share.

Even if we were to look at the expected earnings for the current year, Facebook is expensively priced. Analysts expected Facebook to earn around 50 cents per share in 2012. This means that the forward price to earnings ratio of the company is at 76.5($38.23/50cents). Google’s forward price to earnings ratio for 2012 works out to 14, making Facebook more than five times as expensive as Google.

Let us get into little more detail here. Both Google and Facebook have around 900million users. “There isn’t much scope for growth here, really – we’re beginning to run out of connected adults on the planet,” points out venture capitalist Mahesh Murthy on his Facebook page.

Google had sales of $39.98billion with a profit of $10.83billion. From almost a similar number of users Facebook had sales of $3.71billion and profits of $1billion. Hence Google makes average revenue of around $44per user. At the same time Facebook makes average revenue of around $4 per user. It is rather ironic that even though Google has average revenue per user 11 times that of Facebook and also earned a profit which was nearly 11times, the price to earnings ratio of Facebook is 5 times that of Google.

So what are investors paying for?

Investors are essentially paying for the future growth of Facebook. As Kevin Landis chief investment officer at Firsthand Capital, a Facebook holder told Barrons Online “The investment thesis is pretty simple. Facebook knows more things about more people than does Google, and those people have stronger emotional connections and loyalty because that’s where their friends are…So given a few years to figure it out, Facebook could end up being worth more than Google, which has a market value of $200 billion.”

One advantage with more user data is that Facebook can help advertisers reach their targeted audience better. When companies advertise in mass market mediums like newspapers or television channels they have no clue of whether they are reaching their target audience. But with Facebook they can be sure.

At least the story being bandied around by analysts who are bullish on the stock. But companies aren’t buying this yet. In fact General Motors, a company with one of the largest advertising budgets in the United States, recently pulled its ads from Facebook, cancelling its $10million Facebook advertising budget.

As Matthew Yeomans wrote in a recent column on www.guardian.co.uk “GM clearly believes Facebook users aren’t engaging in banner and targeted advertising and, in that analysis, the company is probably right. Frankly I’ve never met a single person (apart from those who work in the digital advertising industry) who believe online banner ads are effective”.

This is something I totally agree with. What makes it even worse on Facebook is its cluttered look. In fact I only realised that my homepage on Facebook page has ads when I went looking for them. In comparison the Google.com page has a very clean look and with a white background the targeted ads are easily available.

Given this Facebook might find it a little difficult to grow its revenues. As Murthy puts it “This (the valuation of Facebook) might make sense if there was room for Facebook to grow. Where is that? More ads per user? Would we really like that? More charges per ad? Advertisers are already smarting at FB’s rates. Will you pay for apps on their store? Will you pay for premium listings? Not many will, I believe. The point is that FB will find it hard to grow its revenues per user – which is around $4 per year now.”

In fact the revenue growth of Facebook is slowing. Its revenues for the first quarter of 2012 stood at $1.06billion in comparison to $1.13billion in the fourth quarter of 2011. The primary reason for the same is the fact that more and more users are accessing Facebook from their smartphones. And smartsphone screens do not lend themselves well to advertising. Facebook admitted to this in a recent filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, the stock market regulator in the United States, where it said “we do not currently directly generate any meaningful revenue from the use of Facebook mobile products, and our ability to do so successfully is unproven.”

The bubble signs

Other than the basic doubt on the business model (i.e. how does the company plan to make money) of Facebook, there are other signs also of why the company is in bubbly territory. Too many analysts are bullish on it.

Towards the end of the dotcom bubble in 1999, even though the stock market had gone up too soon too fast, most the stock recommendations from the analysts remained a buy i.e. the analysts of Wall Street were commending investors to buy stocks even at very high levels.

According to data from Zack Investment Research only about 1% of the recommendations on some 6000 companies were sell recommendations. The remaining 99% was divided between 69.5% buy recommendations and 29.9%hold recommendations(i.e. don’t buy more shares but don’t sell what you already have).

Analysts typically do not like issuing sell recommendations (or in the case of Facebook asking investors not to buy the stock) because that did not put them in the good books of the company involved. This would mean that the company would stop sharing information and deny the analyst access to its top people. And what good is an analyst who has no access to information on the company he is covering.

Henry Blodget one of the premier analysts during the days of the dotcom boom is quoted as saying in Andy Kessler’s Wall Street Meat “You’ve got to understand. If I stop recommending stock and the shares keep going up, there is hell to pay. Brokers call you up and yell to you for missing more of the upside. Bankers yell at you for messing up their relationships. There is just too much risk in not recommending these stocks.”

Facebook is in a similar situation. Analysts are predicting that Facebook will grow its profits by 38% and its revenues by 35% on an average over the course of the next three years. This is groupthink at its worst.

Another thing that happened during dotcom bubble was the fact that the valuations of the dotcom companies with no business models were worth much more than companies which had genuine businesses in place which had been generating revenue for years. Priceline.com sold its shares at $16 and ended its first day of trading at $69. The website basically resold airline tickets and did not own any airplanes, but was worth more than the entire tangible airline industry put together.

Valuations had reached crazy levels. eToys a tiny seller of toys on the web with revenues of $25million was listed on the stock exchanges at a market capitalization of three times the value of Toys “R” Us, a company with tangible business and stores throughout the United States generating a revenue of $11billion.

While the situation is nowhere as crazy now as it was back then but it is a tad similar. At its current market capitalization of around $104.6billion, Facebook is worth as much as PepsiCo, a company which has been in the business for years. PepsiCo has a sales of $67billion with profits of around $6billion. While people may call PepsiCo an old economy stock but it can be pointed out that the company still has huge scope to expand across large parts of Asia and Africa where the annual per capita consumption of cold drinks continues to remain low.

In comparison there is not much scope for Facebook to grow from its current levels as far as number of users is concerned.

To conclude:

Warren Buffett one of the greatest investors of our times did not invest in any of the dotcom stocks in the late 1990s. His returns fell for a few years and he was also the laughing stock of the market. But when the bubble burst and billions of dollars of investor money were lost, Buffett was the last man standing. What he wrote in his annual letter to the shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway for the year 2000 after the dotcom bubble burst is worth repeating here:

By shamelessly merchandising birdless bushes, promoters have in recent years moved billions of dollars from the pockets of the public to their own purses (and to those of their friends and associates). The fact is that a bubble market has allowed the creation of bubble companies, entities designed more with an eye to making money off investors rather than for them. Too often, an IPO, not profits, was the primary goal of a company’s promoters. At bottom, the “business model” for these companies has been the old-fashioned chain letter, for which many fee-hungry investment bankers acted as eager postmen.

But a pin lies in wait for every bubble. And when the two eventually meet, a new wave of investors learns some very old lessons: First, many in Wall Street – a community in which quality control is not prized – will sell investors anything they will buy. Second, speculation is most dangerous when it looks easiest.

And for all we know Facebook might just be a passing fad. I would like to conclude with something a gentleman by the name of Marc Effron, the President of The Talent Strategy Group, and author of One Page Talent Management, told me a few months back, when I asked him if Facebook was just a passing fad. “The first thing that comes to my mind when you say Facebook is MySpace,” he replied.

(The article originally appeared at www.firstpost.com on May 19,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/investing/facebook-is-a-bubble-and-it-will-burst-316100.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

What Ramdev, Biyani, Mallya and Govt can learn from Buffet

Vivek Kaul

So what is common to Baba Ramdev, Kishore Biyani, Vijay Mallya and the government of India, other than the fact that they have all been in the news lately? To put it simply, they all like operate in areas where they lack expertise and in the process make a mess of it.

Let us start Baba Ramdev who became a household name by selling the benefits of Yoga to the masses. He claimed that even diseases like cancer could be cured through yoga. Those who have seen his yoga DVDs will recall the line “karte raho, cancer ka rog bhi theek hoga”.

So far so good. Then he decided that he had enough of preaching yoga and wanted to get into politics and vowed to get all of India’s black money hoarded abroad, back to India. The politicians in the government clearly did not like this (for obvious reasons) and went hammer and tongs after him. Stories were leaked to the media about the wealth he had accumulated over the years and that damaged his credibility as a yoga guru as well. Ramdev has continued in his attempts to establish himself as a politician but with very little success.

Kishore Biyani brought the retail revolution to India, having been inspired by Sam Walton who started Wal-Mart. His retail businesses were doing decently well till he decided to get into a wide variety of businesses from launching an insurance company to even selling mobile phone connections. When times were good he accumulated a lot of debt in trying to grow fast. Now he is in trouble in trying to service the debt and rumors are flying thick and fast that he is planning to sell Big Bazaar, his equivalent of Wal-Mart. This after he sold controlling stake in the cloths retailer, Pantaloons.

Vijay Mallya started Kingfisher Airlines in 2005, going beyond his core business of alcohol. Kingfisher now has accumulated losses of over Rs 6000 crore, and has never made money since its launch. The lack of focus has hurt Mallya’s core alcohol business and United Spirits is no longer India’s most profitable alcohol company. That tag now belongs to the Indian division of the French giant Pernod Ricard.

And finally the government of India, which has been bailing out the troubled airline Air India over and over again. The pilots of the airline keeps going on strike and the government keeps putting a few thousand crores every few months, to keep running the airline.

So the question that crops up here is what is Baba Ramdev doing in politics? Why is Kishore Biyani trying to sell insurance and mobile phone connections to you? And why are Vijay Mallaya and the government of India trying to run an airline?

They would be better off concentrating on things they are good at. These are things they shouldn’t be doing. It is not their area of expertise or what they are good at. The days when individuals, businesses and even governments could be an expert at many things at the same time are long gone.

In the last 100 years there have been only two individuals who have won the Noble prize twice for two different subjects. Marie Curie won the physics prize in 1903 and the Chemistry prize in 1911. Linus Pauling won it twice, the Chemistry Prize in 1954 and Peace Prize in 1962.

So in the strictest sense of the term, Marie Curie is the only person ever to have won a Noble prize in two different subjects and that happened almost 100 years back. This is primarily because as more and more things have been invented and discovered, subjects have become more complex requiring full time attention and expertise.

What is true about individuals is also true about businesses. The expertise and the attention required to run a business has increased over the year. Hence, the moment a businessman tries to go outside its area of expertise, he loses focus, and the chances of the new business doing well are remote.

Let’s take the case of DLF, the biggest real estate company in the country. It tried getting into the insurance and mutual fund business. It had to sell its stake in the mutual fund business and if news reports are to be believed it is trying to lower its stake in the insurance venture by selling its stake to HCL. Now why is a computer major trying to buy into an insurance business which is losing money, is beyond me?

Satyam was in good shape till it remained an IT company. The moments its owner developed aspirations beyond IT and got the company into real estate and infrastructure space, trouble cropped up. Real estate companies have tried unsuccessfully to get into the luxury hotel business and hotels have tried unsuccessfully to get into the luxury apartment business.

Reliance Industries attempts in the retail business haven’t gone anywhere. Anil Ambani who had build a good business in Reliance Capital is struggling with Reliance Communications and Reliance Power. Subrata Roy’s attempts to diversify into the film and television business have come a cropper, with the film business of Sahara, more or less being shutdown. NDTV, a premier English news channel, tried getting into the entertainment channel business with NDTV Imagine. It had to sell out. Cigarette major ITC has been trying to establish itself in the FMCG business for years now. Though it has had some success at it, the business hardly throws up any money in comparison to its cigarette business. All kinds of entrepreneurs have gone into the insurance business in India and are now struggling. This includes Kishore Biyani. At the same time the Tatas have been struggling with their telecom business for years.

There is a thing or two all these guys can learn from internationally renowned investor Warren Buffett. During the period of 1994-2000, the United States saw a whole lot of dotcom companies coming up with their initial public offerings. Some of these shares achieved astonishing highs. The shares of Netscape Communications Corporation, an internet browser company which controlled 75% of the browser market, were sold to investors at $28 per share. When the stock was listed on August 9,1995, it went to $74.75 during the course of the day and finally closed at $58.25, doubling in a single day. Another stock booksamillion.com went up by 973% to $47 in the course of just three days in November 1998. theGlobe.com which listed on November 13,1998, gained 606% during the course of the day and closed at a price of $63.50.

Despite these humungous gains Warren Buffett did not invest a single penny in these stocks. He did not understand the business models of these stocks and remain focused on his investment philosophy of “value investing”. Not surprisingly he had the last laugh as dotcom and technology stocks started crashing after they had peaked in March 2000.

Buffett did not abandon his core philosophy of value investing just because there was “easy money” to be made somewhere else. And he came out on top, for the simple reason that he chose to remain focused on what he knew.

But this is rarely the case. When times are good and there is a lot of easy money floating around every entrepreneur likes to “expand” his business and get into other things. But in this day and age, when things are as complicated and competitive as they are, diversification into different businesses rarely works.

Businesses these days need full time attention from entrepreneurs. Let’s take a look at the airline business. As Warren Buffett put it in a letter he wrote to the shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway “The worst sort of business is one that grows rapidly, requires significant capital to engender the growth, and then earns little or no money. Think airlines. Here a durable competitive advantage has proven elusive ever since the days of the Wright Brothers. Indeed, if a farsighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favor by shooting Orville down…The airline industry’s demand for capital ever since that first flight has been insatiable. Investors have poured money into a bottomless pit, attracted by growth when they should have been repelled by it.”

The reason airline businesses burn capital endlessly is for the simple reason that airlines have very little control over their cost. The major expense in running an airline is oil (the company can lease the aircraft it doesn’t have to always buy them). And oil prices have been over $100 per barrel for a while now. Airline companies have no control over this price, though they can hedge themselves by buying derivatives. But that can be a risky business as well.

So higher the oil price, higher is the cost of running an airline and given the lure of owning an airline, the sector remains a very competitive one, all over the world. Hence companies cannot always pass on an increase in their costs to the end customers though higher ticket prices. Given these reasons airlines are a specialised business, which require full time attention. It is definitely not a business which Vijay Mallya can look to successfully manage, busy as he is running his diverse businesses of alcohol and real estate, indulging in expensive hobbies like IPL and Formula 1, and cheaper ones like commenting regularly on Twitter.

The government of India falls in the same category. Its primary area of activity is governing the nation(which it is anyway making a mess of) and not running an airline. It simply doesn’t have the expertise to run one. Southwest Airlines is successful because it has remained focused on the airlines business. It did not suddenly decide to launch a new beer just because their airline business was constantly throwing up cash over the years.

Kishore Biyani should learn from his inspiration Wal-Mart. The company did not get into the insurance business. They did not say “now that we have so many people coming to our stores, let’s try and sell insurance to them along with fast moving consumer goods”. Or as Warren Buffett puts it ” If you buy things you don’t need, you’ll soon sell things you need.”

That leaves Baba Ramdev. He can learn from his more famous predecessor the Sai Baba of Puttaparthi. Given the following he had he could have easily gotten into politics. But that would have put him at the same pedestal as the politicians who looked up to him as their guru. And thus rightly he did not.

Marketing guru Al Ries has said in the past “Focus is the essence of marketing and branding.” I guess it’s time to rephrase that phrase. “Focus is the essence of marketing, branding and business”. And its time Ramdev, Biyani, Mallya, the government and many others learnt that lesson.

(The article originally appeared on May 10,2012 at http://www.firstpost.com/business/what-ramdev-biyani-mallya-and-govt-can-learn-from-buffett-304770.html).

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])