Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

Hindi film songs have words of wisdom for almost all facets of life. Even inflation.

As the lines from a song in the 1974 superhit Roti, Kapda aur Makan go “Baaki jo bacha mehangai maar gayi(Of whatever was left inflation killed us).”

Inflation or the rise in prices of goods and services has been killing Indians over the last few years. What has hurt the common man even more is food inflation. Food prices have risen at a much faster pace than overall prices.

A discussion paper titled Taming Food Inflation in India released by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices(CACP), Ministry of Agriculture, on April 1, 2013, points out to the same. “Food inflation in India has been a major challenge to policy makers, more so during recent years when it has averaged 10% during 2008-09 to December 2012. Given that an average household in India still spends almost half of its expenditure on food, and poor around 60 percent (NSSO, 2011), and that poor cannot easily hedge against inflation, high food inflation inflicts a strong ‘hidden tax’ on the poor…In the last five years, post 2008, food inflation contributed to over 41% to the overall inflation in the country,” write the authors Ashok Gulati and Shweta Saini. Gulati is the Chairman of the Commission and Saini is an independent researcher.

During the period 2008-2009 to December 2012, the wholesale price inflation, a measure of the overall rise in prices, averaged at 7.4%. In the same period the food inflation averaged at 10.13% per year.

So who is responsible for food inflation, which is now close to 11%? The short answer is the government. As Gulati and Saini write “The Economist in its February 2013 issue highlights that it was the increased borrowings by the Indian government which fuelled inflation…It categorically puts the responsibility on the government for having launched a pre-election spending spree in 2008, which continued even thereafter.”

Gulati and Saini build an econometric model which helps them conclude that “fiscal Deficit, rising farm wages, and transmission of the global food inflation; together they explain 98 percent of the variations in Indian food inflation over the period 1995-96 to December, 2012…These empirical results clearly indicate that it would not be incorrect to blame the ballooning fiscal deficit of the country today to be the prime reason for the stickiness in food inflation.”

Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends. In the Indian context, it has been growing in the last few years as the government has been spending substantially more than what it has been earning.

The fiscal deficit of the Indian government in 2007-2008 (the period between April 1, 2007 and March 31, 2008) stood at Rs 1,26,912 crore. This jumped by 230% to Rs 4,18,482 crore, in 2009-2010 (the period between April 1, 2009 and March 31, 2010). This was primarily because the expenditure of the Congress led UPA government went up at a much faster pace than the income.

The government of India had a total expenditure of Rs 7,12,671 crore, during the course of 2007-2008. This grew by nearly 44% to Rs 10,24,487 crore in 2009-2010. The income of the government went up at a substantially slower pace. Between 2007-2008 and 2009-2010, the revenue receipts (the income that the government hopes to earn every year) of the government grew by a minuscule 5.7% to Rs 5,72,811 crore.

And it is this increased expenditure(reflected in the burgeoning fiscal deficit) of the government that has led to inflation. As Gulati and Saini point out “Indian fiscal package largely comprised of boosting consumption through outright doles (like farm loan waivers) or liberal increases in pay to organised workers under Sixth Pay Commission and expanded MGNREGA(Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act expenditures for rural workers. All this resulted in quickly boosting demand.”

So the increased expenditure of the government was on giving out doles rather than building infrastructure.

This meant that the money that landed up in the pockets of citizens was ready to be spent and was spent, sooner rather than later. “But with several supply bottlenecks in place, particularly power, water, roads and railways, etc, very soon, ‘too much money was chasing too few goods’. And no wonder, higher inflation in general and food inflation in particular, was a natural outcome,” write the authors.

So increased expenditure of the government led to increasing demand for goods and services. This increase in demand was primarily responsible for the economy growing by 8.6% in 2009-2010 and 9.3% in 2010-2011(the period between April 1, 2010 and March 31, 2011). But the increase in demand wasn’t met by an increase in supply, simply because India did not have the infrastructure required for increasing the supply of goods and services. And this led to too much money chasing too few goods.

No wonder this sent food prices spiralling. Food prices have continued to rise as the government expenditure has continued to go up. Also food prices have risen at a much faster pace than overall prices. This is primarily because agricultural prices respond much more to an increase in money supply vis a vis manufactured goods where prices tend to be stickier due to some prevalence of long term contracts. As Gulati and Saini put it “In fact, our analysis for the studied period shows that one percent increase in fiscal deficit increases money supply by more than 0.9 percent.”

The other major reason for a rising food prices is the rising cost of food production due to rising farm wages. This pushes inflation at two levels. First is the fact that an increase in farm wages drives up farm costs and that in turn pushes up prices of agricultural products. As the authors point out “During 2007-08 to 2011-12, nominal wages increased at much faster rate, by close to 17.5% per annum…The immediate impact of these increased farm wages is to drive-up the farm costs and thus push-up the farm prices, be it through the channel of MSP(minimum support price) or market forces.”

Rising farm wages also lead to a section of population eating better and which in turn pushes up price of protein food. As Gulati and Saini point out “This study finds that the pressure on prices is more on protein foods (pulses, milk and milk products, eggs, fish and meat) as well as fruits and vegetables, than on cereals and edible oils, especially during 2004-05 to December 2012. This normally happens with rising incomes, when people switch from cereal based diets to more protein based diets.”

In the recent past price of cereals like rice and wheat has also gone up substantially. This is primarily because the government is hoarding onto much more rice and wheat than it requires to distribute under its various social programmes.

If food inflation has to come down, the government has to control expenditure. The authors Gulati and Saini suggest several ways of doing it. The government can hope to earn Rs 80,000-100,000 crore if it can get around to selling the excessive grain stocks that it has. Other than help control its fiscal deficit, the government can also hope to control the price of cereals like rice and wheat which have been going up at a very fast rate by increasing their supply in the open market.

As the authors write “By liquidating(i.e selling) excessive grain stocks in the domestic market or through exports, massive savings of non-productive expenditures can be realized. For example, as against a buffer stock norm of 32 million tonnes of grains, India had 80 million tonnes of grains on July 1, 2012, and this may cross 90 million tonnes in July 2013. Even if one wants to keep 40 million tonnes of reserves in July, liquidating the remaining 50 million tonnes can bring approximately Rs 80,000-100,000 crore back to the exchequer. And with this much grain in the market food inflation will certainly come down. Else, the very cost of carrying this “extra” grain stocks alone will be more than Rs 10,000 crore each year, counting only their interest and storage costs.”

Of course this has its own challenges. More than half of this inventory of grain in India is concentrated in the states of Punjab and Haryana. Moving this inventory from Punjab and Haryana to other parts of the country will not be easy, assuming that the government opts to work on this suggestion. At the same time the government will have to do it in a way so as to ensure that the market prices of rice and wheat don’t collapse. And that is easier said than done.

The authors also recommend that the government can cut down on food and fertiliser subsidy by directly distributing it. “By going through cash transfers route (using Aadhar), one can plug in leakages in PDS(public distribution system) which, as per CACP calculations are around 40%, and save on high costs of storage and movement too, saving in all about Rs 40,000 crore on food subsidy bill,” write Gulati and Saini.

Something similar can be done on the fertiliser front as well. “Fertiliser subsidy, if given directly to farmers on per hectare basis (Rs 4000/ha to all small and marginal farmers which account for about 85 percent of farmers; and somewhat less (Rs 3500 and Rs 3000/ha) as one goes to medium and large farmers, and deregulating the fertiliser sector can bring in large savings of about Rs 20,000 crore along with greater efficiency in production and consumption of fertilisers.”

Whether the government takes these recommendations of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices seriously, remains to be seen. Meanwhile here is another brilliant Hindi film song from the 2010 hit Peepli Live: “Sakhi saiyan khoobai kaamat hain, mehangai dayan khaye jaat hai(O friend, my beloved earns a lot, but the inflation demon keeps eating us up).”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on April 2, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

UPA

How Mamata is denting the rupee and bloating the oil bill

Vivek Kaul

A major reason for announcing the so called economic reforms that the Manmohan Singh UPA government did over the last weekend was to get India’s burgeoning oil subsidy bill which was expected to cross Rs 1,90,000 crore during the course of the year, under some control.

One move was the increase in diesel price by Rs 5 per litre and limiting the number of cooking gas cylinders that one could get at the subsidisedprice to six per year. This was a direct step to reduce the loss that the oil marketing companies (OMCs) face every time they sell diesel and cooking gas to the end consumer.

The other part of the reform game was about expectations management. The announcement of reforms like allowing foreign direct investment in multi-brand foreign retailing or the airline sector was not expected to have any direct impact anytime soon. But what it was expected to do was shore up the image of the government and tell the world at large that this government is committed to economic reform.

Now how does that help in controlling the burgeoning oil bill?

Oil is sold internationally in dollars. The price of the Indian basket of crude oil is currently quoting at around $115.3 per barrel of oil (one barrel equals around 159litres).

Before the reforms were announced one dollar was worth around Rs 55.4(on September 13, 2012 i.e.). So if an Indian OMC wanted to buy one barrel of oil it had to convert Rs 6387.2 into $115.3 dollars, and pay for the oil.

After the reforms were announced the rupee started increasing in value against the dollar. By September 17, one dollar was worth around Rs 53.7. Now if an Indian OMC wanted to buy one barrel of oil it had to convert Rs 6191.6 into $115.3 to pay for the oil.

Hence, as the rupee increases in value against the dollar, the Indian OMCs pay less for the oil the buy internationally. A major reason for the increase in value of the rupee was that on September 14 and September 17, the foreign institutional investors poured money into the stock market. They bought stocks worth Rs 5086 crore over the two day period. This meant dollars had to be sold and rupee had to be bought, thus increasing the demand for rupee and helping it gain in value against the dollar.

But this rupee rally was short lived and the dollar has gained some value against the rupee and is currently worth around Rs 54.

The question is why did this happen? Initially the market and the foreign investors bought the idea that the government was committed at ending the policy logjam and initiating various economic reforms. Hence the foreign investors invested money into the stock market, the stock market rallied and so did the rupee against the dollar.

But now the realisation is setting in that the reform process might be derailed even before it has been earnestly started. This was reflected in the amount of money the foreign investors brought into the stock market on September 18. The number was down to around Rs 1049.2 crore. In comparison they had invested more than Rs 5080 crore over the last two trading sessions.

Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress, a key constituent of the UPA government, has decided to withdraw support to the government. At the same time it has asked the government to withdraw a major part of the reforms it has already initiated by Friday. If the government does that the Trinamool Congress will reconsider its decision.

How the political scenario plays out remains to be seen. But if the government does bow to Mamata’s diktats then the economic repercussions of that decision will be huge. The government had hoped that the losses on account of selling, diesel, kerosene and cooking gas, could have been brought down to Rs 1,67,000 crore, from the earlier Rs 1,92,000 crore by increasing the price of diesel and limiting the consumption of subsidised cooking gas.

If the government goes back on these moves, the oil subsidy bill will go back to attaining a monstrous size. Also, what the calculation of Rs 1,67,000 crore did not take into account was the fact that rupee would gain in value against the dollar. And that would have further brought down the oil subsidy bill. In fact HSBC which had earlier forecast Rs 57 to a dollar by December 2012, revised its forecast to Rs 52 to a dollar on Monday. But by then the Mamata factor hadn’t come into play.

If the government bows to Mamata, the rupee will definitely start losing value against the dollar again. This will happen because the foreign investors will stay away from both the stock market as well as direct investment. In fact, the foreign direct investment during the period of April to June 2012 has been disastrous. It has fallen by 67% to $4.41billion in comparison to $13.44billion, during the same period in 2011. If the government goes back on the few reforms that it unleashed over the last weekend, foreign direct investment is likely to remain low.

One factor that can change things for India is the if the price of crude oil were to fall. But that looks unlikely. The immediate reason is the tension in the Middle East and the threat of war between Iran and Israel. Hillary Clinton, the US Secretary of State, recently said that the United States would not set any deadline for the ongoing negotiations with Iran. This hasn’t gone down terribly well with Israel. Reacting to this Benjamin Netanyahu, the Prime Minister of Israel said “the world tells Israel, wait, there’s still time, and I say, ‘Wait for what, wait until when? Those in the international community who refuse to put a red line before Iran don’t have the moral right to place a red light before Israel.” (Source: www.oilprice.com)

Iran does not recognise Israel as a nation. This has led to countries buying up more oil than they need and building stocks to take care of this geopolitical risk. “In the recent period, since the start of 2012, the increase in stocks has been substantial, i.e. 2 to 3 million barrels per day. These are probably precautionary stocks linked to geopolitical risks,” writes Patrick Artus of Flash Economics in a recent report titled Why is the oil price not falling?

At the same time the United States is pushing nations across the world to not source their oil from Iran, which is the second largest producer of oil within the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec). This includes India as well.

With the rupee losing value against the dollar and the oil price remaining high the oil subsidy bill is likely to continue to remain high. And this means the trade deficit (the difference between exports and imports) is likely to remain high. The exports for the period between April and July 2012, stood at $97.64billion. The imports on the other hand were at $153.2billion. Of this, $53.81billion was spent on oil imports. If we take oil imports out of the equation the difference between India’s exports and imports is very low.

Now what does this impact the value of the rupee against the dollar? An exporter gets paid in dollars. When he brings those dollars back into the country he has to convert them into rupees. This means he has to buy rupees and sell dollars. This helps shore up the value of the rupee as the demand for rupee goes up.

In case of an importer the things work exactly the opposite way. An importer has to pay for the imports in terms of dollars. To do this, he has to buy dollars by paying in rupees. This increases the demand for the dollar and pushes up its value against the rupee.

As we see the difference between imports and exports for the first four months of the year has been around $55billion. This means that the demand for the dollar has been greater than the demand for the rupee.

One way to fill this gap would be if foreign investors would bring in money into the stock market as well as for direct investment. They would have had to convert the dollars they want to invest into rupees and that would have increased the demand for the rupee.

The foreign institutional investors have brought in around $3.86billion (at the current rate of $1 equals Rs 54) since the beginning of the year. The foreign direct investment for the first three months of the year has been at $4.41 billion.

So what this tells us that there is a huge gap between the demand for dollars and the supply of dollars. And precisely because of this the dollar has gained in value against the rupee. On April 2, 2012, at the beginning of the financial year, one dollar was worth around Rs 50.8. Now it’s worth Rs 54.

This situation is likely to continue. And I wouldn’t be surprised if rupee goes back to its earlier levels of Rs 56 to a dollar in the days to come. It might even cross those levels, if the government does bow to the diktats of Mamata.

This would mean that India would have to pay more for the oil that it buys in dollars. This in turn will push up the demand for dollars leading to a further fall in the value of the rupee against the dollar.

Since the government forces the OMCs to sell diesel, kerosene and cooking gas much below their cost to consumers, the losses will continue to mount. The current losses have been projected to be at Rs 1,67,000 crore. I won’t be surprised if they cross Rs 2,00,000 crore. The government has to compensate the OMCs for these losses in order to ensure that they don’t go bankrupt.

This also means that the government will cross its fiscal deficit target of Rs 5,13,590 crore. The fiscal deficit, which is the difference between what the government earns and what it spends, might well be on its way to touch Rs 7,00,000 crore or 7% of GDP. (For a detailed exposition of this argument click here). And that will be a disastrous situation to be in. Interest rates will continue to remain high. And so will inflation. To conclude, the traffic in Mumbai before the Ganesh Chaturthi festival gets really bad. Any five people can get together while taking the Ganesh statue to their homes, put on a loudspeaker, start dancing on the road and thus delay the entire traffic on the road for hours. Indian politics is getting more and more like that.

Reforms, like the traffic, may have to wait. Mamata’s revolt is single-handedly worsening the oil bill, thanks, in part, to the rupee’s worsening fortunes. By not raising prices now, the subsidy bill bloat further, and in due course we will be truly in the soup.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on September 20, 2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/how-mamata-is-denting-the-rupee-and-bloating-the-oil-bill-461919.html

Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected]

Mute Manmohan watches as “Coalgate” engulfs Congress from all sides

Vivek Kaul

The Great Fire of Rome started on July 19, 64AD, and burnt for six days. There are several varying accounts of it in history. One of the accounts suggests that Nero the king of Rome watched the fire destroy the city, from one of Rome’s many hills, while singing and playing the lyre, a stringed musical instrument.

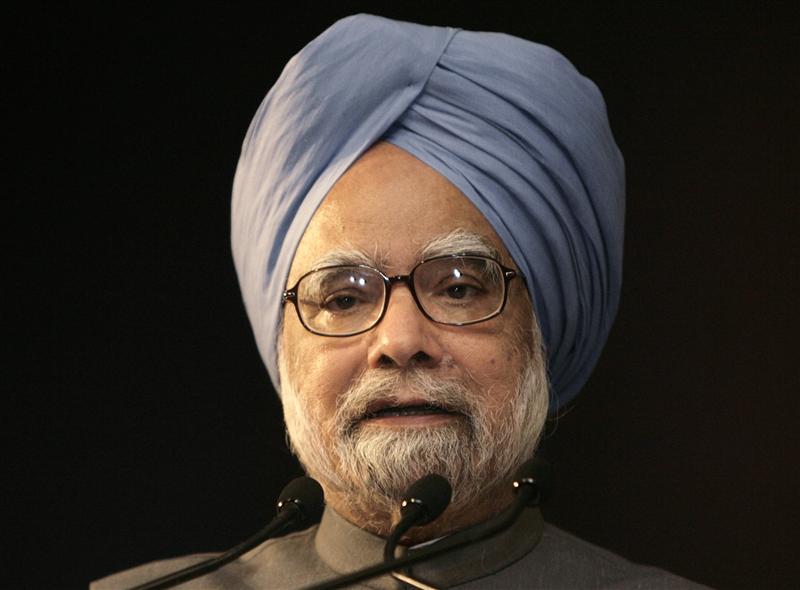

India these days has its own Nero, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. As the Congress led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government gets engulfed in the coal-gate scam, Manmohan Singh has largely been a silent spectator watching from the stands and seeing his government being engulfed by the coal fire.

And this is not the first time. Manmohan Singh has largely been a bystander at the helm of what is turning out to be probably the most corrupt government that India has ever seen. As TN Ninan, one of the most respected business editors in the country, recently wrote in the Business Standard “Corruption silenced telecom, it froze orders for defence equipment, it flared up over gas, and now it might black out the mining and power sectors. Manmohan Singh’s fatal flaw — his willingness to tolerate corruption all around him while keeping his own hands clean — has led us into a cul de sac , with the country able to neither tolerate rampant corruption nor root it out.”

Manmohan Singh like Nero before him has been watching as institutionalised corruption burns India. The biggest of these scams has been termed “coal-gate” by the Indian media. The Comptroller and the Auditor General (CAG) of India put the losses on account of this scam at a whopping Rs 1,86,000 crore.

The background

The Planning Commission of India had estimated that the raw demand for coal in the year 2011-2012 will be at around 696 million tonnes. Of this 554 million tonnes was expected to be produced in the country by Coal India, Singareni Collieries and a host of other small companies. The remaining was expected to be met through imports.

Production of coal in 2011-2012 in million tonnes

Company Target Achievement

Coal India 447 436

Singareni Collieries 51 52

Others 56 52

Total 554 540

Source: Provisional Coal Statistics 2011-2012, Coal Controller Organisation, Ministry of Coal

As can be seen from the table above the actual production of coal at 540 million tonnes was a little less than the target. This was an increase of 1.3% over the previous year. Also since the actual demand for coal was significantly higher than the actual production, India had to import a lot of coal during the course of the year. Estimates made by the Coal Controller Organisation suggest that the country imported around 99million tonnes of coal in 2011-2012. The Planning Commission had expected around 137million tonnes to be imported in the year. So the Coal Controller’s estimate for coal imports is significantly lower than that. Also the increasing iport of coal is not a one off trend.

Coal Imports In Million tonnes In Rupees crore

1999-2000 19.7 3548

2000-2001 20.9 4053

2001-2002 20.5 4536

2002-2003 23.3 5028

2003-2004 21.7 5009

2004-2005 29 10266

2005-2006 38.6 14910

2006-2007 43.1 16689

2007-2008 49.8 20738

2008-2009 59 41341

2009-2010 73.3 39180

2010-2011 68.9 41550

2011-2012 98.9 45723*

*from April-Oct 2011

Source: Provisional Coal Statistics 2011-2012, Coal Control Organisation, Ministry of Coal

As the above table suggests India has been importing more and more coal since the turn of the century. A major reason for this has been the inability of the government owned Coal India, which is the largest producer of coal in the country, to increase production at a faster rate. Between 2004-2005 and 2011-2012 the company managed to increase its production by just 65million tonnes to 436million tonnes, an absolute increase of around 17.5%. The import of coal went up by a massive 241% to around 99 million tonnes, during the same period.

In fact, to its credit, the government of India realised the inability of the country to produce enough coal in the early 1990s. The Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act 1973 was amended with effect from June 9, 1973, to allow the government to give away coal blocks for free for captive use of coal. The Economic Survey for 1994-95 points out the reason behind the decision: “In order to encourage private sector investment in the coal sector, the Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act, 1973 was amended with effect from June 9, 1993 for operation of captive coal mines by companies engaged in the production of iron and steel, power generation and washing of coal in the private sector.”

The total coal production in the country in 1993-94 stood at 246.04million tonnes having grown by 3.3% from 1992-93. The government understood that the production was not going to increase at a faster rate anytime soon because the newer projects were having time delays and cost overruns. As the 1994-95 economic survey put it “As on December 31,1994, out of 71 projects under implementation in the coal sector, 22 projects are bedeviled by time and cost over-runs. On an average, the time overrun per project is about 38months.There is urgent need to improve project implementation in the coal sector”.

The last few years

The idea of giving away coal blocks for free was to encourage investment in coal by companies which were dependant on coal as an input. This included companies producing power, iron and steel and cement. Since the government couldn’t produce enough coal to meet their needs, the companies would be allowed to produce coal to meet their own needs by giving them coal blocks for free.

While the policy to give away coal blocks has been in place since 1993, it didn’t really take off till the mid 2000s. Between 1993 and 2003, the government gave away 39 coal blocks free to private companies as well as government owned companies. 20 out of the 39 blocks were allocated in 2003.

In the year 2004, the government gave away four blocks. But these were big blocks with the total geological reserves of coal amounting to 2143.5million tonnes. After this the floodgates really opened up and between 2005 and 2009, 149 coal blocks were given away for free.

Year Number of mines Geological Reserves (in million tonns)

2004 4 2143.5

2005 21 3174.3

2006 47 14424.8

2007 45 10585.8

2008 21 3423.5

2009 15 6549.2

153 40301.1

Source: Provisional Coal Statistics 2011-2012, Coal Control Organisation, Ministry of Coal

The above table makes for a very interesting reading. Between 2004 and 2009, the government of India gave away 153 coal blocks with geological reserves amounting to a little more than 40billion tonnes for free. Estimates made by the Geological Survey of India suggest that India has 293.5billon tonnes of coal reserves. This implies that the government gave away 13.7% of India’s coal reserves for free in a period of just five years.

The Congress led United Progressive Alliance was in power for most of this period with Manmohan Singh having been sworn in as the Prime Minister in May 2004. Interestingly, things reached their peak between 2006 and 2009, when the Prime Minister was also the Minister for Coal. During this period 128 coal blocks with geological reserves amounting to around 35billion tonnes were given away for free. But giving away the coal blocks for free did not solve any problem. As per the report prepared the Comptroller and Auditor General of India, as on March 31, 2011, eighty six of these blocks were supposed to produce around 73million tonnes of coal. Only 28 blocks have started production and their total production has been around 34.6million tonnes, as on March 31,2011.

The CAG and the losses

As is clearly explained above the Manmohan Singh led UPA government gave away around 14% of nation’s coal reserves away for free. Nevertheless, several senior leaders of the Congress party have told the nation that there have been no losses on account of the coal blocks being given away for free, primarily because very little coal was being produced from these blocks.

P Chidamabaram, the finance minister recently said “If coal is not mined, where is the loss? The loss will only occur if coal is sold at a certain price or undervalued.” Digvijaya Singh, a senior Congress leader targeted Vinod Rai, the Comptroller and Auditor General. Singh told The Indian Express that “the way the CAG is going, it is clear he(i.e. Vinod Rai) has political ambitions like TN Chaturvedi (a former CAG who later joined the BJP). He has been giving notional and fictional figures that have no relevance to facts. How has he computed these figures? He is talking through his hat.”

This is sheer nonsense to say the least and anyone who understands how CAG arrived at the loss number of Rs 1,86,000 crore wouldn’t say so.

The CAG reasonably assumed that the coal mined from the coal blocks given away for free could have been sold at a certain price in the market. Since the government gave away the blocks for free it lost that opportunity. This lost opportunity is what CAG has tried to quantify in terms of a number.

While calculating the loss the CAG did not take into account the coal blocks given to the government companies. Only blocks given to private companies were taken into account. Further only open cast mines were included in calculating the loss. Underground mines were not taken into account.

Also, the total coal available in a block is referred to as geological reserve. Due to several reasons including those of safely, the entire geological reserve cannot be mined. The portion that can be mined is referred to as extractable reserve. The extractable reserves for the blocks (after ignoring the blocks owned by government companies and underground mines) came to 6282.5million tonnes. This is equivalent to more than 14 times the annual production of Coal India Ltd.

The government could have sold this coal at a certain price. Also mining this coal would have involved a certain cost. The CAG first calculated the average sale price for all grades of coal sold by Coal India in 2010-2011. This came to Rs 1028.42 per tonne. Then it calculated the average cost of production for all grades of coal for the same period. This came at Rs 583.01. Other than this there was a financing cost of Rs 150 per tonne which was taken into account, as advised by the Ministry of Coal. Hence a benefit of Rs 295.41 per tonne of coal was arrived at (Rs 1028.42 – Rs 583.01 – Rs 150). The losses were thus estimated to be at Rs 1,85,591.33 crore (Rs 295.41 x 6282.5million tonnes) or around Rs 1.86lakh crore, by the CAG.

Chidambaram and Singh were basically trying to confuse us by mixing two issues here. One is the fact that the government gave away the blocks for free. And another is the inability of the companies who got these blocks to start mining coal. Just because these companies haven’t been able to mine coal doesn’t mean that the government of India did not face a loss by giving away the mines for free.

What are the problems with the CAG’s loss calculation?

The problem with CAG’s loss calculation is that it doesn’t take into account the time value of money. The government wouldn’t have been able to sell all the coal all at once. It would have only been able to do so over a period of time. The CAG doesn’t take this into account. Ideally, it should have assumed that the government earns this revenue over a certain number of years and then discounted those revenues to arrive at a present value for the losses.

This goes against the government. But there are several assumptions that favour the government. The coal blocks given away free to government companies aren’t taken into account. The transaction of handing over a coal block was between two arms of the government. The ministry of coal and a government owned public sector company (like NTPC). In the past when such transactions have happened the profit earned from such transactions have been recognised. A very good example is when the government forces the Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) of India to buy shares of public sector companies to meet its disinvestment target. One arm of the government (LIC) is buying shares of another arm of the government (for eg: ONGC). And the money received by the government is recognised as revenue in the annual financial statement. So when revenues for transactions between two arms of the government are recognised so should losses. Around half of the coal blocks were given to government owned companies.

Also, the price at which Coal India sells coal to companies it has an agreement with, is the lowest in the market. It is not linked to the international price of coal. The price of coal that is auctioned by Coal India is much higher than its normal price. As the CAG points out in its report on the ultra mega power project, the average price of coal sold by Coal India through e-auction in 2010-2011 was Rs 1782 per tonne. The average price of imported coal in November 2009 was Rs 2874 per tonne (calculated by the CAG based on NTPC data). The CAG did not take into account these prices. It took into account the lowest price of Rs 1028.42 per tonne, which was the average Coal India price.

Let’s run some numbers to try and understand what kind of losses CAG could have come up with if it wanted to. At a price of Rs 1,782, the profit per tonne would have been Rs 1050 (Rs 1782-Rs 583.01- Rs 150). If this number had been used the losses would have amounted to Rs6.6lakh crore.

At a price of Rs 2874 per tonne, the profit per tonne would have been Rs 2142(Rs 2874 – Rs 583.01 – Rs 150). If this number had been used the losses would have been Rs 13.5lakh crore. This number is a little more than the Rs 13.18 lakh crore expenditure that the government of India incurred in 2011-2012.

So there are weaknesses in the CAG’s calculation of the losses on account of coal blocks being given away free. But these weaknesses work in both the directions. The bottomline though is that the country has suffered a big loss, though the quantum of the loss is debatable.

To conclude

News reports suggest that several Congress politicians have benefitted from the coal blocks being given away for free. The companies which got coal blocks haven’t been able to produce coal. The government hasn’t been able to invoke the bank guarantees of the companies for the delay in producing coal. This is because of a flaw in the allocation letters. As the Business Standard reports “There is a technical flaw in the format of the allocation letters. As per the letters, the government can invoke the bank guarantee clause only in cases of less production, and not nil production.” Some companies have started selling power in the open market. This power is being produced from the coal they mined out of the coal blocks they got free from the government.

The situation has all the facets of turning into a big mess like the previous scams under the Congress led UPA regime. And like the previous scams, it is likely to be swept under the carpet as well. Despite all this, the Prime Minister Manmohan Singh will continue to be a mute spectator to all this, keeping the chair warm till Rahul Gandhi is ready to take over. I would be glad to be proven otherwise.

(The article originally appeared in The Seasonal Magazine on September 12,2012. http://www.seasonalmagazine.com/2012/09/mute-manmohan-watches-as-coalgate.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Canaries and coal mines

Vivek Kaul

Music has got its share of one hit wonders. Delhi born singer and musician Peter Saerdest fits that category. His most famous claim to fame being the 1969 hit “where do you go to (my lovely)”.

The song is about a fictional girl called Marie Clare. There is a paragraph in the song which brings out the unhappiness in her life. Here is how it goes:

But where do you go to my lovely

When you’re alone in your bed

Tell me the thoughts that surround you

I want to look inside your head, yes i do.

Now this is a question that I have been wanting to ask the Prime Minister (PM) Manmohan Singh as the country moves from one scam to another. What are the thoughts that go inside his head? The forever quiet PM finally obliged us when he issued a statement on the coal gate scam and put the blame on his predecessors and the Comptroller and Auditor General(CAG) of India, for coming up with a loss number of Rs 1.86 lakh crore.

The policy of the government allocating coal blocks for free was introduced in 1993, and so it was not right to blame the Congress led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) felt the Prime Minister. Fair point, one must say.

But as the numbers calculated by the international stock brokerage CLSA show a major part of the coal blocks were given away for free only after the Congress led UPA came to power in May 2004. Of the 100 coal blocks given away free to government companies between 1993 and 2011, 83blocks were handed over after 2003. The same stands true for private sector companies where 82 out of the 106 blocks were allocated after 2003.

So while it might be true that UPA did not start the policy but what Manmohan Singh cannot deny is that they went around implementing it with a vengeance. The geological reserves of the coal blocks given away for free amounted to around 41billion tonnes. The total geological reserves of coal in India amount to around 286billion tonnes which means 14% of it was given away for free.

Hence, the question that the PM still needs to answer is that why was there a sudden increase in the allocation of blocks between 2004 and 2009, and especially during his tenure as the coal minister between 2006 and 2009?

The answer might most probably lies in the price of coal which started to shoot up around the time UPA first came to power. Prices shot up from around $30-40 per tonne to around $190 per tonne internationally in mid 2008. The conclusion that one can draw from this is that before 2004 it was cheap to just buy coal off the market. But after that things changed and it made more sense for companies to have direct access to coal.

The PM in his statement has also claimed that the loss number of Rs 1.86 lakh crore arrived at by the CAG can be questioned on a number of technical points.

The CAG has calculated the loss number based on certain assumptions. It has only taken into account mines given to private sector companies for free. Those allotted to government companies have been ignored. Underground mines have also not been taken into consideration.

So these assumptions work in favour of the government. If the government blocks had also been taken into account the loss number would have dramatically shot up. It need not be said that the PM does not talk about this anywhere in his statement.

The extractable reserves of these private sector coal blocks come to 6282.5million tonnes of coal. This is the amount of coal that the CAG feels could have been mined and sold and has been given away for free. The average benefit per tonne of this coal was estimated to be at Rs 295.41.

As Abhishek Tyagi and Rajesh Panjwani of CLSA write in a report dated August 21, 2012,”The average benefit per tonne has been arrived at by first, taking the difference between the average sale price (Rs1028.42) per tonne for all grades of CIL(Coal India Ltd) coal for 2010-11 and the average cost of production (Rs583.01) per tonne for all grades of CIL coal for 2010-11. Secondly, as advised by the Ministry of Coal vide letter dated 15 March 2012 a further allowance of Rs150 per tonne has been made for financing cost. Accordingly the average benefit of Rs295.41 per tonne has been applied to the extractable reserve of 6282.5 million tonne calculated as above.”

Using this method CAG arrived at the loss figure of Rs 1,85,591.33 crore (Rs 295.41 x 6282.5million tonnes) or around Rs 1.86 lakh crore. Analysts who track coal believe that assuming a profit of Rs 295.41 per tonne is a fairly conservative estimate.

In fact as has been reported elsewhere, if the e-auction prices of coal would have been considered, the losses would have been at Rs 11.2lakh crore. And if the calculations had been done using the imported coal prices the losses would amount to Rs 18lakh crore. These are huge numbers. The total expenditure of the government of India for the year 2011-2012 was estimated to be at around Rs 13.2lakh crore.

Another bogey that has been raised by the sympathizers of the Congress party (not by the PM) is that coal is a natural resource and hence cannot be “auctioned” or sold at a market price. What they forget to tell us is that coal is a limited natural resource and hence it needs to be priced correctly and not given away for free. If that was not the case why does the government price products like petrol, diesel, telecom spectrum etc? These products are also either natural resources or derivatives of natural resources. Why does Coal India Ltd sell coal at a certain price? Why not give it away for free?

By giving away coal blocks for free the nation has faced huge losses. Whether its Rs 1.86 lakh crore or Rs 18 lakh crore is a matter of conjecture, but that does not take away the fact that losses have been huge. Given this, the PM and the Congress party, are just trying to practice the old adage: “if you can’t convince them, confuse them”.

(The article originally appeared on Asian Age/Deccan Chronicle on September 2,2012. http://www.deccanchronicle.com/editorial/dc-comment/canaries-coal-951)

(Vivek Kaul is a Mumbai based writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

Raghuram Rajan’s advice isn’t what UPA may want to hear

Vivek Kaul

Every year the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, one of the twelve Federal Reserve Banks in the United States, organizes a symposium at Jackson Hole in the state of Wyoming. The conference of 2005 was to be the last conference attended by Alan Greenspan, the then Chairman of the Federal Reserve of United States, the American central bank.

Hence, the theme for the conference was the legacy of the Greenspan era. One of the economists who had been invited to present a paper at the symposium was the 40 year old Raghuram Govind Rajan, the man who is likely to be the government’s next Chief Economic Advisor.

Rajan is an alumnus of IIT Delhi, IIM Ahmedabad and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). After doing his PhD at MIT, he had joined the Graduate School of Business at the University of Chicago (now known as the Booth School of Business). At that point of time Rajan was on leave from the business school and was working as the Chief Economist at the International Monetary Fund.

The United States had seen an era of unmatched economic prosperity under Greenspan. Even, the dotcom bust in 2000-2001 hadn’t held America back. Greenspan had managed to get the economy back on track by cutting the Federal Funds Rate to as low as 1% by mid 2003. The low interest rate scenario along with a lot of financial innovation had created a financial system which was slush with money. American banks were falling over one another to lend money. And borrowers were borrowing as much as they could to buy homes, property and real estate. The dotcom bubble of the late 1990s had given away to the real estate bubble.

In a survey of home buyers carried out in Los Angeles in 2005, the prevailing belief was that prices will keep growing at the rate of 22% every year over the next 10 years. This meant that a house which cost a million dollars in 2005 would cost around $7.3million by 2015. Such was the belief in the bubble.

And the belief was not limited to only the people of United States. Banks were equally optimistic that real estate prices will continue to go up. Between 2004 and 2006, banks and other financial institutions playing in the subprime home loan space gave out loans worth $1.7trillion in total. Of this a massive $625billion was lent in 2005, the year Rajan was invited to speak at Jackson Hole.

In its strictest sense a subprime loan was defined as a loan given to an individual with a credit score below 620, who had no assets and was thus unlikely to qualify for a traditional home loan. A credit score is a number calculated on the basis of the borrower’s past record at paying bills and loans of all kinds, the length of his credit history, the kind of loans taken etc. On the basis of the number the lender can get some sort of an idea of what sort of a risk he is taking on by lending to the borrower.

That was the purported idea behind the credit score. In the normal scheme of things, a borrower categorized as “sub-prime” should not have been touched with a bargepole. But those were days when everybody and anybody got a loan.

It was an era of optimism which had been fueled by easy money that was going around in the financial system. The conventional wisdom of the day was that the bull run in property prices would continue forever. The American economy would continue to prosper.

In this environment Raghuram Rajan presented a paper titled “Has Financial Development Made the World Riskier?” In his speech Rajan harped on the fact that the era of easy money would get over soon and would not last forever as the conventional wisdom expected it to.

He said:

The bottom line is that banks are certainly not any less risky than the past despite their better capitalization, and may well be riskier. Moreover, banks now bear only the tip of the iceberg of financial sector risks…the interbank market could freeze up, and one could well have a full-blown financial crisis

He also suggested in his speech that the incentives of the financial sector were skewed and employees were reaping in rich rewards for making money but were only penalized lightly for losses. In the last paragraph of his speech Rajan said it is at such times that “excesses typically build up. One source of concern is housing prices that are at elevated levels around the globe.”

Rajan’s speech did not go down well with people at the conference. This is not what they wanted to hear. Also in a way Rajan was questioning the credentials of Alan Greenspan who would soon retire spending nearly 18 years as the Chairman of the Federal Reserve of United States. He was essentially saying that the Greenspan era was hardly what it was being made out to be.

Given this, Rajan came in for heavy criticism. As he recounts in his book Fault Lines – How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy:

Forecasting at that time did not require tremendous prescience: all I did was connect the dots… I did not, however, foresee the reaction from the normally polite conference audience. I exaggerate only a bit when I say I felt like an early Christian who had wandered into a convention of half-starved lions. As I walked away from the podium after being roundly criticized by a number of luminaries (with a few notable exceptions), I felt some unease. It was not caused by the criticism itself…Rather it was because the critics seemed to be ignoring what going on before their eyes.

The criticism notwithstanding Rajan turned out right in the end. And what was interesting that he called it as he saw it. He called spade a spade despite the aura of Alan Greenspan that prevailed.

What this story clearly tells us is that Rajan is not an “on-the-other-hand” economist. There are too many “on-the-other-hand” economists going around, who do not like to take a stand on an issue. As Harry Truman, an American President once famously said “All my economists say, ‘on the one hand… and on the other hand…Someone give me a one-handed economist!”

If news-reports in the media are to be believed the government is in the process of appointing Rajan as the Chief Economic Advisor to replace Kaushik Basu. As far as academic credentials and experience go they don’t come much better than Rajan. Other than having been the Chief Economist of the IMF between September 2003 and January 2007, he is also currently an honorary economic adviser to the Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.

The question though is will the plain-speaking Rajan who seems to like to call a spade a space, fit into a government which believes in the idea of a welfare state? In an interview I did for the Daily News and Analysis (DNA) after the release of his book Fault Lines I had asked him “whether India can afford a welfare state?” “Not at the level that politicians want it to. For example, the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS), if appropriately done it is a short term insurance fix and reduces some of the pressure on the system, which is not a bad thing. But if it comes in the way of the creation of long term capabilities, and if we think NREGS is the answer to the problem of rural stagnation, we have a problem. It’s a short term necessity in some areas. But the longer term fix has to be to open up the rural areas, connect them, education, capacity building, that is the key,” Rajan had replied.

This is a view that is not held by many in the present United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government. They politicians who run this country have great faith in the NREGS.

Rajan had also written in Fault Lines that “the license permit raj has given away to the raj of the land mafia.” I had asked him to explain this in detail and he had said:

“Earlier…you had to navigate the government for permissions and this was license permit. You needed permission to produce. Now you have to navigate the government for land because in many situations land titles are murky, acquiring the land is difficult, and even after you acquire protecting that land is difficult. So there are entrepreneurs who have access to the power of the government, who basically can do it. And then there are others who can’t. So you have made it a test of who can acquire the land in certain kind of functions than who is the best developer than who is the best manufacturer. Put differently what used to surround the license permit has moved to corruption surrounding land. The central source of wealth today in the whole economy is land and we need to make the land acquisition process transparent.”

In answer to another question Rajan had said:

“The predominant of the sources of mega wealth in India today are not the software billionaires who have made money the hard way by being competitive in a global economy. It is the guys who have access to natural resources or to land or to particular infrastructure permits or licenses. In other words proximity to the government seems to be a big source of wealth. And that is worrisome because it means that those who can access the government who can manage it are in a sense far more powerful than ordinary businessmen. In the long run this leads to decay in the image of businessmen and the whole free enterprise system. It doesn’t show us in good light if we become a country of oligopolies and oligarchs and eventually this could even impinge on democratic right.”

What these answers tell us is that Rajan has clear views on issues that plague India and he is not afraid of putting them forward. But these are things that the current government would not like to hear. Given this, it remains to be seen how effective Rajan’s tenure in the government will turn out to be. The trouble is if he calls a spade a spade, it won’t take much time for the government to marginalize him. If he does not, he won’t be effective anyway.

(The interview originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 8,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/raghuram-rajans-advice-isnt-what-upa-may-want-to-hear-410694.html/)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected] )