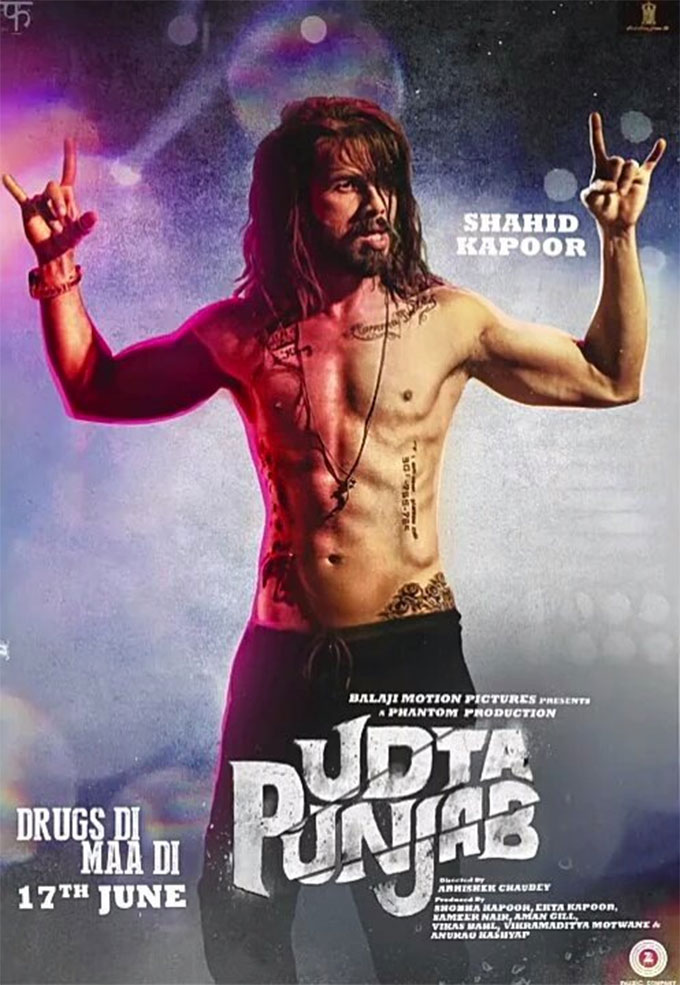

The recent release Udta Punjab highlighted the problem of drug addiction in Punjab. While, drug addiction is a global problem, Punjab has nearly 3.3 times more drug addicts per lakh than the Indian national average.

And why is that the case? From the supply side, the state shares a border with Pakistan. Hence, drugs are easy to smuggle in. The demand side is a little more complicated to explain.

The state saw a Green revolution starting in the mid-1960s, with the agricultural yield exploding, thanks to C. Subramaniam, the food and agriculture minister back then.

Subramanian came to know of a form of wheat developed in Mexico which could rapidly raise output. As Gurcharan Das writes in India Unbound: “C. Subramaniam was a man in a hurry and he chartered several Boeing 707s and flew in 16,000 metric tons of seed of this miracle wheat…Punjabi farmers still speak lovingly of Mexico’s Lerma Rojo, one of the earliest varieties to take root in their soil.”

And thus started the green revolution in Punjab. In order to support this, the government also started to procure rice and wheat directly from the farmers through the Food Corporation of India and other state procurement agencies.

The higher yields along with assured procurement led to the farmers of Punjab progressing. While the procurement policy is supposed to be pan India, the procurement is limited largely to a few states. As the Economic Survey for 2015-2016 points out: “In Punjab and Haryana, almost all paddy and wheat farmers are aware of the [procurement] policy.” In 2013-2014, Punjab produced 11.1 million tonnes of rice. Of this, 8.1 million tonnes was procured by the government. This is the highest in the country.

What also helped is that there is no tax on agricultural income. Also, free power is available for farming. All this, has helped the Punjabi farmer. The first generation worked hard to spread the green revolution. The second generation carried on the good work. And the third generation, born into money, is enjoying the spoils.

This is along the lines of what happens to a typical family owned business. As Das writes, taking the example of Buddenbrooks by Thomas Mann, which he feels is the finest book ever written about family business: “It describes the saga of three generations; in the first generation the scruffy and astute patriarch works hard and makes money. Born into money, the second generation does not want more money…The third generation dedicates itself to art. So the aesthetic but physical weak grandson plays music. There is no one to look after the business and it is the end of the Buddenbrook family.”

Something similar seems to have happened in Punjab, where some part of the third generation has moved away from farming and gotten into drugs, given the access to easy money they have, due to the hard work put in by their grandparents. Some evidence of this can easily be found in the kind of songs that Punjabi popstars sing these days. The word dope, weed etc., keep cropping up in these songs.

The other interesting thing is the number of super expensive brand names that these songs refer to and espouse. From Jaguar to Audi to Gucci to Armani, they seem to have it all. This seems to be a good indicator of the fact that some part of the third generation after the Green revolution started, has gone away from farming and gotten into other things.

No other state in India (except perhaps Haryana) has this kind of music. What has helped is the astonishing rise in the price of land in the state. Also, land acquisition in Punjab is easier compared to many other Indian states given that the average size of a landholding in Punjab is around 9.3 acres, which is much bigger than many Indian states. Hence, large parcels of land are easier to buy.

Land sale has also brought in a lot of easy money. And some of this seems to have leaked into drugs.

The column originally appeared in the Bangalore Mirror on June 29, 2016