Vivek Kaul

P Chidambaram, the union finance minister, has been urging Indians not to buy gold. But we just won’t listen to him.

In the month of May 2013, India imported $8.4 billion worth of gold, up by 90% in comparison to May 2012. This surge in gold imports pushed up the trade deficit to $20.14 billion in May. It was at $17.8 billion during April 2013. Trade deficit is the difference between the merchandise imports and exports. Commerce Secretary S R Rao said “As far as trade deficit is concerned, it is very worrisome…It is largely contributed by heavy imports of gold and silver.”

A trade deficit means that the country is not earning enough dollars through exports to pay for all that it is importing. To correct this, it either needs to increase its exports and earn more dollars to pay for imports or cut down on its imports. Indian exports have been growing at a very slow pace. In fact they fell by 1.1% in May 2013 to $24.5 billion. Imports on the other hand rose by 7% to $44.65 billion.

The trouble is that when India imports gold it pays for it in dollars. Indian rupees are sold to buy these dollars. Given this there is a surfeit of rupees in the market and a scarcity of dollars, pushing up the value of the dollar against the rupee. This leads to the country paying more for imports in rupee terms.

Hence, the logic goes that India should not be importing as much gold as it is. Or as Chidambaram said a few days back “I would once again appeal to everyone please resist the temptation to buy gold…If I have one wish which the people of India can fulfill is don’t buy gold.”

But the same logic applies to oil as well. India imported $15 billion worth of oil in May 2013. Of course, oil is more useful than gold, and we need to import it because we don’t produce enough of it.

And given that gold is as useless as something can be, we don’t need to import it. Or as Chidambaram said “I continue to hope and suppose if the people of India don’t demand gold if we don’t have to import gold for a year just imagine the whole situation will so dramatically change. Every ounce of gold is imported. You pay in rupees, we have to provide dollars.”

So what comes out of all this is that the government does not want Indians to buy gold. It recently increased the import duty on gold to 8% from 6% earlier. Chidambaram even set a personal example when he recently said “I don’t buy gold, I put my money in financial instruments and I am happy.”

There are multiple problems with what Chidambaram is saying. The first and foremost is the fact that buying or not buying gold is a free economic decision that people choose to make. Or as economist Bibek Debroy wrote in a column in The Economic Times “The gold policy is futile because buying gold is a free decision of rational economic agents and gold imports are a symptom, not the disease.”

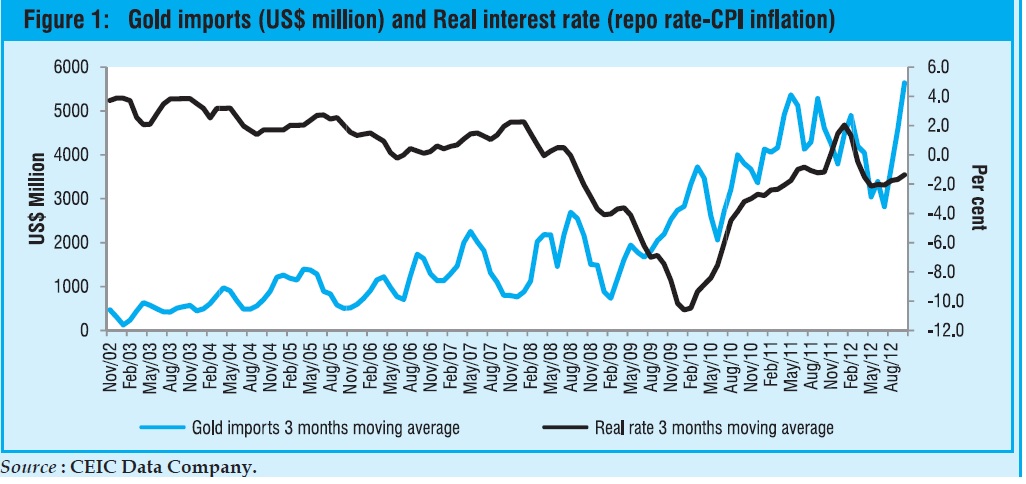

And what is the symptom? The symptom is the high consumer price inflation that prevails. People have been buying gold to hedge themselves against that inflation. As the Economic Survey of the government for the year 2012-2013, released in February pointed out “Gold imports are positively correlated with inflation: High inflation reduces the return on other financial instruments. This is reflected in the negative correlation between rising imports and falling real rates.”

What this means is that because inflation is high the real rate of return on financial instruments is very low. Why would people invest in a financial instrument like a fixed deposit or a PPF account or a National Savings Certificate, at an interest of 8-9%, when the consumer price inflation is higher than that? So what do they do? They invest in gold because they have been told over the generations, that gold holds its value against inflation.

Chidambaram has asked people not to buy gold and even gone to the extent of saying that he does not buy the yellow metal and puts his money in financial instruments. Of course, being the finance minister of the country he is unlikely to face any problems while investing in financial instruments.

But here is a small suggestion. Chidambaram should try investing in a mutual fund once on his own without going through a bank or an agent. And the bizarre number of requirements that need to be fulfilled to invest in a mutual fund, will give him a real flavour of how difficult it is to invest for an individual to invest in a mutual fund.

Or take the case of a senior citizen who invests his retirement funds in the senior citizen savings scheme run by the post office and is given a thorough run-around every time he has to go and collect the interest on the money that he has deposited.

Or take case of the spate of smses banks recently sent out to their customers asking them to furnish documents and account opening recommendations, even when customers have had accounts for more than a decade.

Given this, it is not surprising that people buy gold which is available hassle free over the counter. The Economic Survey nailed it when it said “The overarching motive underlying the gold rush is high inflation and the lack of financial instruments available to the average citizen, especially in the rural areas. The rising demand for gold is only a “symptom” of more fundamental problems in the economy. Curbing inflation, expanding financial inclusion…and improving saver access to financial products are all of paramount importance.” Hence, people will continue to buy gold when they want to, irrespective of the appeals made by Chidambaram.

Inflation is something that the government of this country has created. And when people protect themselves against it, you can’t hold them responsible for creating other problems.

When a country runs a trade deficit it doesn’t earn enough dollars to pay for its imports through exports. What happens in this situation is that dollars coming in through other sources like foreign direct investment, foreign institutional investment and citizens living abroad, are used to finance imports.

In India’s case remittances a well as deposits made by NRIs play an important part in filling up the trade deficit gap. As Andy Mukherjee points out in a column in the Business Standard “For every rupee of time deposits that Indian banks have raised from residents in the past year, 13

paise has come from the estimated 25 million people of Indian origin who live in other countries.”

World over interest rates on savings deposits are at very low levels. The same is not true about India where interest rates continue to remain high and hence it makes sense for NRIs to invest money in India.

But this investment carries the currency risk. Lets understand this through an example. An NRI decides to invest $100,000 in India. At the point of time he gets his money into India, one dollar is worth Rs 50. So he has got Rs 50 lakh to invest. He invests this in a bank which is offering him 10% interest. At the end of the year he gets Rs 55 lakh (Rs 50 lakh + 10% interest on Rs 50 lakh).

Now lets say a year later $1 is worth Rs 55. So when the NRI converts Rs 55 lakh into dollars, he gets $100,000 (Rs 55 lakh/55) or the amount that he had invested initially. Hence, he does not make any return in the process. This is because the Indian rupee has depreciated against the dollar, which is something that has been happening lately. This is the currency risk.

In this scenario, the NRIs are likely to withdraw their deposits from India because if the rupee keeps losing value against the dollar, chances are they might face losses on their investments. When NRIs repatriate their money, they sell rupees and buy dollars. This leads to a surfeit of rupees and shortage of dollars in the market, and thus leads to the rupee depreciating further.

This is a scenario that is likely to play out in the days to come. Over and above this there is also the danger of foreign institutional investors continuing to withdraw money from the Indian debt market, as they have in the recent past.

This danger has become even more pronounced with Ben Bernanke, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve of United States, the American central bank, announcing late last night that they would go slow on money printing.

As he said “the Committee currently anticipates that it would be appropriate to moderate the monthly pace of purchases later this year.”

The Federal Reserve prints dollars and uses them to buy bonds to pump money into the financial system. This ensures that interest rates continue to remain low as there is enough money going around.

As and when the Federal Reserve goes slow on money printing, the American interest rates will start to go up (in fact they have already started to go up). Given this the investors who had been borrowing in the United States and using that money to invest in India, would be looking at a lower return as they will have to pay a higher interest on their borrowing.

A prospective lower return could lead to some of these investors to sell out of India. In fact as I write this the bond market has come to a halt because there are only sellers in the market and no buyers. Such has been the haste to exit India.

When foreign investors sell out of bonds (and stocks for that matter) they get paid in rupees. This money needs to be repatriated to the United States and hence needs to be converted into dollars. So the rupees are sold to buy dollars from the foreign exchange market.

When this happens there is a surfeit of rupees in the market and a huge demand for dollars. This has led to the rupee rapidly losing value against the dollar. Around one month back one dollar was worth Rs 55. Now its worth close to Rs 60 ($1 equals Rs 59.9 to be precise).

A lower rupee means that the price of gold is likely to go up in rupee terms. And this can attract more investors into gold pushing up India’s gold import bill further. But then do we blame for the gold investor for that? And if that is the case why not ban all speculation, starting with real estate.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on June 20, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

trade deficit

Gold fever accelerates, never mind the trade deficit

Vivek Kaul

The law of demand in economics states that all other things remaining the same, the demand for a good is inversely proportional to its price. So if the price falls, the demand goes up and vice versa.

This identity holds on a lot of occasions but not on all occasions.

Allow me to elaborate.

Indian gold and silver imports for the month of April 2013, were at $7.5 billion. This was 138% more than imports during April 2012. This has come across a surprising development for many. “The rise in gold imports is surprising,” Trade Secretary S.R. Rao told reporters at a press conference after the import numbers came out. “It wasn’t expected,” he added.

In fact predictions made by people who follow the gold market closely were exactly the opposite. Mohit Kamboj had told PTI in middle of last month that “the imports of the yellow metal is likely to be 25 per cent less than the corresponding month last year as the gold prices are declining steadily.” He has been way off the mark. Kamboj is the President of the Bombay Bullion Association.

So why did Rao find this sudden increase in the import of gold surprising? Or why did Kamboj expect gold imports to fall?

The rise in gold imports is in line with the law of demand. As gold prices fell, people got out and bought more of it. The trouble is that people were buying more gold even when its price was going up. As economists Sonal Varma and Aman Mohunta of Nomura wrote in a report titled India: Correlation between gold prices and demand released on April 23, 2013, “The correlation between the gold price and gold demand (import volume) in India shifted from being negative pre-2008 to positive since 2009. This means that in recent years a rising gold price was accompanied by rising demand, and vice-versa.”

So people were buying gold when its price was going up and now people are buying gold again, when its price has crashed. Also in between gold imports fell as gold prices crashed. Between January and March 2013, India imported 200 tonnes of gold which was around 23.7% lower than during the same period in 2012.

Let me rephrase the entire argument again then. People were buying gold when its prices were going up. People went slow on buying gold when its prices were coming down. And people are now buying gold again with a vengeance, when the prices have crashed and have started to go up again.

How do we explain this? What is happening here? Maggie Mahar has some sort of an answer for this in her book Bull – A History of the Boom and Bust, 1982-2004. As she writes “In the normal course of things, higher prices dampen desire. When lamb becomes too dear, consumers eat chicken; when the price of gasoline soars, people take fewer vactations. Conversely, lower prices usually whet our interest: colour TVs, VCRs, and cell phones became more popular as they became more affordable. But when a stock market soars, investors do not behave like consumers. They are consumed by stocks. Equities seem to appeal to the perversity of human desire. The more costly the prize, the greater the allure.”

Replace the word ‘equity’ with gold here and the argument stays the same. When the price of gold was going up, people were looking to make a quick buck because they expected that the price of gold will continue to go up, and so they bought. Hence, higher prices of gold, led to higher demand and thus to higher imports in the Indian case. It is important to remember here that those who were buying gold at higher prices were looking at it as a mode of investment/speculation.

When the price of the yellow metal started to fall, the speculators got out of the race. And thus the demand fell, and so did the imports. After the price had fallen sufficiently enough, only then did the consumers of gold start to buy it. It is important to remember that world over gold is looked upon as a hedge against inflation but in India it is a hedge against inflation as well as a consumable good. Gold jewellery is a very important part of the Indian way of life. And once prices had fallen to the levels they have in the last one month, it is this demand that has come in and pushed up gold imports by 138%.

Hence, those making predictions on gold, should well remember that in India, it is both a mode of investment/speculation as well as a consumable good. And when prices fell, it is those who look at gold as a consumable good, start buying.

As Sonal Varma and Aman Mohunta of Nomura write in a report titled India: Trade deficit worsened sharply in April on higher gold imports released on May 13,2013 “The recent fall in gold prices suggests that gold import volumes should moderate this year. This is not yet happening, but we see the recent rise in gold imports as a bunched up rise in consumption demand, which should fade over the coming quarters.”

Of course this is assuming that the price of gold continues to remain flat. If it starts to rise (in fact it has already risen by more than 5% from the low of $1360 per ounce (1 troy ounce equals 31.1 grams)) then investor/speculator demand will come in again. In fact, if the price of gold falls further, the speculators/investors might come back in again, sensing a good trade.

What this means is that despite massive efforts by the government to bring down gold imports, Indians have continued to buy gold. And since India produces very little amount of gold, it has to import almost all of what it consumes. This is reflected in the trade deficit (or the difference between imports and exports) for the month of April 2013, which has come in at $17.8 billion. This is a jump of 72% from March 2013. Gold and silver imports at $7.5 billion, formed a major part of it. The gold import numbers for May are likely to be high again, given the festival of Askhay Tritya which is being celebrated today (i.e. May 13, 2013) will trigger a rush for the yellow metal. Askhay Tritya is considered to be an auspicious day to buy gold.

Since gold is imported, a demand for gold triggers a demand for dollars, which are used to buy gold. And this leads to the rupee losing value against the dollar. This in turn makes other imports like oil and coal also expensive. Hence, efforts have been made by the government in the past to limit gold imports.

To conclude, in March, the finance minister P Chidambaram had told CNBC TV 18 “On gold, I can only appeal to you and through your channel to the people that to not demand so much gold.”

Of course people have gone ahead and done exactly the opposite. Chidambaram had also told CNBC TV 18 “However, I am not sure too many people will listen to me on that.”

Not many did, it seems.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on May 14, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Subsidies = Inflation = Gold problem

The government has a certain theory on gold as per which buying gold is harmful for the Indian economy. Allow me to elaborate starting with something that P Chidambaram, the union finance minister, recently said “I…appeal to the people to moderate the demand for gold.”

India produces very little of the gold it consumes and hence imports almost all of it. Gold is bought and sold internationally in dollars. When someone from India buys gold internationally, Indian rupees are sold and dollars are bought. These dollars are then used to buy gold.

So buying gold pushes up demand for dollars. This leads to the dollar appreciating or the rupee depreciating. A depreciating rupee makes India’s other imports, including our biggest import i.e. oil, more expensive.

This pushes up the trade deficit (the difference between exports and imports) as well as our fiscal deficit (the difference between what the government earns and what it spends).

The fiscal deficit goes up because as the rupee depreciates the oil marketing companies(OMCs) pay more for the oil that they buy internationally. This increase is not totally passed onto the Indian consumer. The government in turn compensates the OMCs for selling kerosene, cooking gas and diesel, at a loss. Hence, the expenditure of the government goes up and so does the fiscal deficit. A higher fiscal deficit means greater borrowing by the government, which crowds out private sector borrowing and pushes up interest rates. Higher interest rates in turn slow down the economy.

This is the government’s theory on gold and has been used to in the recent past to hike the import duty on gold to 6%. But what the theory doesn’t tells us is why do Indians buy gold in the first place? The most common answer is that Indians buy gold because we are fascinated by it. But that is really insulting our native wisdom.

World over gold is bought as a hedge against inflation. This is something that the latest economic survey authored under aegis of Raghuram Rajan, the Chief Economic Advisor to the government, recognises. So when inflation is high, the real returns on fixed income investments like fixed deposits and banks is low. As the Economic Survey puts it “High inflation reduces the return on other financial instruments. This is reflected in the negative correlation between rising(gold) imports and falling real rates.”(as can be seen from the accompanying table at the start)

In simple English, people buy gold when inflation is high and the real return from fixed income investments is low. That has precisely what has happened in India over the last few years. “The overarching motive underlying the gold rush is high inflation…High inflation may be causing anxious investors to shun fixed income investments such as deposits and even turn to gold as an inflation hedge,” the Survey points out.

High inflation in India has been the creation of all the subsidies that have been doled out by the UPA government. As the Economic Survey puts it “With the subsidies bill, particularly that of petroleum products, increasing, the danger that fiscal targets would be breached substantially became very real in the current year. The situation warranted urgent steps to reduce government spending so as to contain inflation.”

Inflation thus is a creation of all the subsidies being doled out, says the Economic Survey. And to stop Indians from buying gold, inflation needs to be controlled. “The rising demand for gold is only a “symptom” of more fundamental problems in the economy. Curbing inflation, expanding financial inclusion, offering new products such as inflation indexed bonds, and improving saver access to financial products are all of paramount importance,” the Survey points out. So if Indians are buying gold despite its high price and imposition of import duty, they are not be blamed.

A shorter version of this piece appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on February 28, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Is Manmohan following Lalu’s no-growth Bihar strategy?

Vivek Kaul

In a piece titled Farewell to Incredible India, which deals with the current economic problems in India, The Economist writes: “The Congress-led coalition government, with Brezhnev-grade complacency, insists things will bounce back.”

Leonid Brezhnev was the General Secretary of the Central Committee (CC) of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). He ruled the country from 1964 till his death in 1982.

I guess The Economist looked too far. They could have found someone right here in India to describe the complacency of the Manmohan Singh-led United Progressive Alliance(UPA) government. The man I am talking about is none other than Lalu Prasad, the former railway minister and former chief minister of Bihar.

Yes, you read it right. Before I get into explaining why I just said what I did, let us go back a little into history.

The lucky Lalu Yadav

Lalu Yadav re-entered politics in 1973, just by sheer chance. He didn’t have to struggle for it. The opportunity just fell into his lap.

As Sankarshan Thakur writes in Subaltern Sahib: Bihar and the Making of Lalu Yadav, “On the eve of elections of Patna University Students Union (PUSU) in 1973 non-Congress student bodies had again come together, if only for their limited purpose of ousting the Congress. But they needed a credible and energetic backward candidate to head the union. Lalu Yadav was sent for.”

The only trouble was that Lalu Yadav was no longer a student, but was an employee of the Patna Veterinary College. He had quit student politics in 1970, after having lost the election for the presidentship of PUSU to a Congress candidate. Before this, Lalu had been the general secretary of PUSU for three consecutive years.

But Lalu got around the problem. “Assured that the caste arithmetic was loaded against the Congress union, Lalu readily agreed to contest. He quietly buried his job at the Patna Veterinary College and got a backdated admission into the Patna Law College. He stood for elections and won. The non-Congress coalition in fact swept the polls,” writes Thakur.

And from there on Lalu Yadav went from strength to strength. In 1974, the students’ agitation against then prime minister Indira Gandhi spread throughout the country. As Thakur points out, “An agitation committee was formed, the Bihar Chatra Sangharsh Samiti to coordinate the activities of various unions and Lalu Yadav as president of PUSU was chosen its chief.”

These events catapulted Lalu Yadav into the big league. In the 1977 elections, Lalu was elected to the Lok Sabha as a Janata Party candidate at a young age of 29.

Chief Minister of Bihar

VS Naipaul once described Bihar as “the place where civilisation ends”. Lalu Prasad first became the chief minister of Bihar in 1990. Between him and his wife Rabri Devi they largely ruled the state till 2005, and almost brought civilisation to an end.

When India was going from strength to strength with economic growth rates that it had never seen before, the economy of Bihar was shrinking in size. As Ruchir Sharma writes in Breakout Nations – In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles , “Bihar was the only Indian state that not only sat out India’s first growth spurt but also saw its economy shrink (by 9 percent) between 1980 and 2003.”

Lalu and his wife Rabri ruled for the major portion of the period between 1980 and 2003. Economic development was nowhere in the agenda of Lalu and on several occasions when questioned about the lack of economic development in the state, he replied that economic development does not get votes. And he was proved right.

In fact such was Lalu’s lack of belief in development that even money allocated to the state government by the Central government remained unspent. As Santhosh Mathew and Mick Moore write in a research paper titled State Incapacity by Design: Understanding the Bihar Story, “Despite the poverty of the state, the governments led by Lalu Prasad signally failed to spend the money actually available to them: ‘…Bihar has the country’s lowest utilisation rate for centrally funded programs, and it is estimated that the state forfeited one-fifth of central plan assistance during 1997–2000.’”

Between 1997 and 2005, the Ministry of Rural Development allocated Rs 9,600 crore. Of this, nearly Rs 2,200 crore was not drawn. And of the money received only 64 percent was spent. Similarly, money allocated from other programmes was also not spent.

How did he survive?

Lalu survived by building a potent combination of MY (Muslim + Yadav) voters. The Yadavs are the single largest caste in Bihar. Such was his faith in the MY voters that Lalu did not even promise development, like most politicians tend to do. As Mathew and Moore write: “He finessed this problem…by departing from the normal practices of Indian electoral politics and not vigorously promising ‘development’. For example, if during his many trips to villages he was asked to provide better roads, he would tend to question whether roads were really of much benefit to ordinary villagers, and suggest that the real beneficiaries would be contractors and the wealthy, powerful people who had cars. He typically required a large escort of senior public officials on these visits, and would require them to line up dutifully and humbly on display while he himself was doing his best to behave like a villager. He might gesture at this line-up and ask ‘Do you really want a road so that people like this can speed through your village in their big cars?’”

So what was Lalu Yadav trying to do here? “Lalu Prasad Yadav was not trying to fool most of his voters most of the time. He was offering then tangible benefits: respect (izzat – a Hindi term that he employed frequently) and the end of local socio-political tyrannies

Where does Manmohan Singh fit in here?

Some time after Lalu Yadav became the chief minister of Bihar, India had a financial crisis. PV Narasimha Rao was looking for a technocrat for the Finance Minister’s position. He first approached Dr Indraprasad Gordhanbhai Patel, who was the Governor of the Reserve Bank of India(RBI) from 1977 to 1982. Patel refused and suggested the name of his successor at the RBI, Manmohan Singh, who had been the Governor of the RBI from 1982 to 1985. Singh had just taken over as the Chairman of the University Grants Commission (UGC) in March 1991. He was pulled out of there and made the Finance Minister of India. And thus started Singh’s second career. Like Lalu, Singh’s career got a second life.

And he, like Lalu, before him went from strength to strength and finally became the Prime Minister of India. A few days ago, Mamata Banerjee had even proposed his name for President. He would make for an excellent President given that the Indian President doesn’t really do anything, except what the government (in this case Sonia) wants him to.

If Pratibha Patil, who no one had ever heard of, could become the President of India, so can the much more loyal Manmohan. He fits all the parameters Sonia Gandhi is looking for in a President. But the trouble, of course, is she wants the same parameters in her Prime Minister as well. And he can’t be at two places at the same time. So Singh’s name as a presidential candidate has been rejected by the Congress party. It would have been a rather glorious end to an “illustrious” career.

The irony

However what is ironic is that a man, who once spearheaded the economic reform process in India, has now totally withdrawn himself from the same. In fact, at times one wonders whether it is even a priority with him and his government? Now that Pranab Mukherjee is leaving the finance ministry for Rashtrapati Bhawan, we will find out what Manmohan has in store.

There has hardly been any response from the UPA government to the recent low GDP growth rate number of 5.3 percent for the period between January and March 2012. Pranab Mukherjee has blamed the slow growth on the problems in Greece in particular and Europe in general. This is a typical Lalu response where the old adage “if you can’t convince them, confuse them” is at work. The problems of India are not because of problems in Greece or Europe, but because of the economic policies of the Manmohan Singh-led UPA government. (It’s not Greece: Cong policies responsible for rupee crash).

As The Economist puts it, “India’s slowdown is due mainly to problems at home and has been looming for a while. The state is borrowing too much, crowding out private firms and keeping inflation high. It has not passed a big reform for years. Graft, confusion and red tape have infuriated domestic businesses and harmed investment. A high-handed view of foreign investors has made a big current-account deficit harder to finance, and the rupee has plunged.”

In fact, there is a state of total denial within the UPA that there are serious economic problems facing India. The spin-doctors of UPA are even working overtime to sell the country that famous song from 3 Idiots “All is Well“. On a recent TV show, Montek Singh Ahulwalia, the deputy chairman of the Planning Commission, kept insisting that a 7 percent economic growth rate was a given. As it turned out the GDP growth rate fell to 5.3 percent.

Economic development doesn’t matter

The way the UPA government has been working over the last few years, it is very easy to conclude that economic development of this country isn’t really top of the agenda. Like was the case with Lalu Yadav.

The solutions to the problems are simple and largely agreed upon by everyone who has an informed opinion on the issue. As The Economist puts it, “The remedies, agreed on not just by foreign investors and liberal newspapers but also by Manmohan Singh’s government are blindingly obvious. A combined budget deficit of nearly a tenth of GDP must be tamed, particularly by cutting wasteful fuel subsidies. India must reform tax and foreign-investment rules. It must speed up big industrial and infrastructure projects. It must confront corruption. None of these tasks is insurmountable. Most are supposedly government policy.”

But then there is hardly any policy coming out of the government. So what is top of the agenda? To stay in power and enjoy its fruits? And by the time the 2014 elections come around, set the stage ready for Rahul Gandhi to take over? But the question that crops up here is this: like Lalu, does the Manmohan Singh-led UPA have a MY formula? And even if it does have a formula, will it work?

Lalu found out in 2005 that formulas become useless over a period of time. “We could not make it because of overconfidence and division in Muslim-Yadav (votes),” Lalu told India Today magazine after his defeat to Nitish Kumar in the 2005 election.

Overconfidence is the word the Manmohan Singh led UPA needs to watch out for.

(The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on June 16,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/politics/is-manmohan-following-lalus-no-growth-bihar-strategy-345933.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Petrol bomb is a dud: If only Dr Singh had listened…

Vivek Kaul

The Congress led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government finally acted hoping to halt the fall of the falling rupee, by raising petrol prices by Rs 6.28 per litre, before taxes. Let us try and understand what will be the implications of this move.

Some relief for oil companies:

The oil companies like Indian Oil Company (IOC), Bharat Petroleum (BP) and Hindustan Petroleum(HP) had been selling oil at a loss of Rs 6.28 per litre since the last hike in December. That loss will now be eliminated with this increase in prices. The oil companies have lost $830million on selling petrol at below its cost since the prices were last hiked in December last year. If the increase in price stays and is not withdrawn the oil companies will not face any further losses on selling petrol, unless the price of oil goes up and the increase is not passed on to the consumers.

No impact on fiscal deficit:

The government compensates the oil marketing companies like Indian Oil, BP and HP, for selling diesel, LPG gas and kerosene at a loss. Petrol losses are not reimbursed by the government. Hence the move will have no impact on the projected fiscal deficit of Rs 5,13,590 crore. The losses on selling diesel, LPG and kerosene at below cost are much higher at Rs 512 crore a day. For this the companies are compensated for by the government. The companies had lost Rs 138,541 crore during the last financial year i.e.2011-2012 (Between April 1,2011 and March 31,2012).

Of this the government had borne around Rs 83,000 crore and the remaining Rs 55,000 crore came from government owned oil and gas producing companies like ONGC, Oil India Ltd and GAIL.

When the finance minister Pranab Mukherjee presented the budget in March, the oil subsidies for the year 2011-2012 had been expected to be at Rs Rs 68,481 crore. The final bill has turned out to be at around Rs 83,000 crore, this after the oil producing companies owned by the government, were forced to pick up around 40% of the bill.

For the current year the expected losses of the oil companies on selling kerosene, LPG and diesel at below cost is expected to be around Rs 190,000 crore. In the budget, the oil subsidy for the year 2012-2013, has been assumed to be at Rs 43,580 crore. If the government picks up 60% of this bill like it did in the last financial year, it works out to around Rs 114,000 crore. This is around Rs 70,000 crore more than the oil subsidy that the government has budgeted for.

Interest rates will continue to remain high

The difference between what the government earns and what it spends is referred to as the fiscal deficit. The government finances this difference by borrowing. As stated above, the fiscal deficit for the year 2012-2013 is expected to be at Rs 5,13,590 crore. This, when we assume Rs 43,580crore as oil subsidy. But the way things currently are, the government might end up paying Rs 70,000 crore more for oil subsidy, unless the oil prices crash. The amount of Rs 70,000 crore will have to be borrowed from financial markets. This extra borrowing will “crowd-out” the private borrowers in the market even further leading to higher interest rates. At the retail level, this means two things. One EMIs will keep going up. And two, with interest rates being high, investors will prefer to invest in fixed income instruments like fixed deposits, corporate bonds and fixed maturity plans from mutual funds. This in other terms will mean that the money will stay away from the stock market.

The trade deficit

One dollar is worth around Rs 56 now, the reason being that India imports more than it exports. When the difference between exports and imports is negative, the situation is referred to as a trade deficit. This trade deficit is largely on two accounts. We import 80% of our oil requirements and at the same time we have a great fascination for gold. During the last financial year India imported $150billion worth of oil and $60billion worth of gold. This meant that India ran up a huge trade deficit of $185billion during the course of the last financial year. The trend has continued in this financial year. The imports for the month of April 2012 were at $37.9billion, nearly 54.7% more than the exports which stood at $24.5billion.

These imports have to be paid for in dollars. When payments are to be made importers buy dollars and sell rupees. When this happens, the foreign exchange market has an excess supply of rupees and a short fall of dollars. This leads to the rupee losing value against the dollar. In case our exports matched our imports, then exporters who brought in dollars would be converting them into rupees, and thus there would be a balance in the market. Importers would be buying dollars and selling rupees. And exporters would be selling dollars and buying rupees. But that isn’t happening in a balanced way.

What has also not helped is the fact that foreign institutional investors(FIIs) have been selling out of the stock as well as the bond market. Since April 1, the FIIs have sold around $758 million worth of stocks and bonds. When the FIIs repatriate this money they sell rupees and buy dollars, this puts further pressure on the rupee. The impact from this is marginal because $758 million over a period of more than 50 days is not a huge amount.

When it comes to foreign investors, a falling rupee feeds on itself. Lets us try and understand this through an example. When the dollar was worth Rs 50, a foreign investor wanting to repatriate Rs 50 crore would have got $10million. If he wants to repatriate the same amount now he would get only $8.33million. So the fear of the rupee falling further gets foreign investors to sell out, which in turn pushes the rupee down even further.

What could have helped is dollars coming into India through the foreign direct investment route, where multinational companies bring money into India to establish businesses here. But for that the government will have to open up sectors like retail, print media and insurance (from the current 26% cap) more. That hasn’t happened and the way the government is operating currently, it is unlikely to happen.

The Reserve Bank of India does intervene at times to stem the fall of the rupee. This it does by selling dollars and buying rupee to ensure that there is adequate supply of dollars in the market and the excess supply of rupee is sucked out. But the RBI does not have an unlimited supply of dollars and hence cannot keep intervening indefinitely.

What about the trade deficit?

The trade deficit might come down a little if the increase in price of petrol leads to people consuming less petrol. This in turn would mean lesser import of oil and hence a slightly lower trade deficit. A lower trade deficit would mean lesser pressure on the rupee. But the fact of the matter is that even if the consumption of petrol comes down, its overall impact on the import of oil would not be that much. For the trade deficit to come down the government has to increase prices of kerosene, LPG and diesel. That would have a major impact on the oil imports and thus would push down the demand for the dollar. It would also mean a lower fiscal deficit, which in turn will lead to lower interest rates. Lower interest rates might lead to businesses looking to expand and people borrowing and spending that money, leading to a better economic growth rate. It might also motivate Multi National Companies (MNCs) to increase their investments in India, bringing in more dollars and thus lightening the pressure on the rupee. In the short run an increase in the prices of diesel particularly will lead higher inflation because transportation costs will increase.

Freeing the price

The government had last increased the price of petrol in December before this. For nearly five months it did not do anything and now has gone ahead and increased the price by Rs 6.28 per litre, which after taxes works out to around Rs 7.54 per litre. It need not be said that such a stupendous increase at one go makes it very difficult for the consumers to handle. If a normal market (like it is with vegetables where prices change everyday) was allowed to operate, the price of oil would have risen gradually from December to May and the consumers would have adjusted their consumption of petrol at the same pace. By raising the price suddenly the last person on the mind of the government is the aam aadmi, a term which the UPAwallahs do not stop using time and again.

The other option of course is to continue subsidize diesel, LPG and kerosene. As a known stock bull said on television show a couple of months back, even Saudi Arabia doesn’t sell kerosene at the price at which we do. And that is why a lot of kerosene gets smuggled into neighbouring countries and is used to adulterate diesel and petrol.

If the subsidies continue it is likely that the consumption of the various oil products will not fall. And that in turn would mean oil imports would remain at their current level, meaning that the trade deficit will continue to remain high. It will also mean a higher fiscal deficit and hence high interest rates. The economic growth will remain stagnant, keeping foreign businesses looking to invest in India away.

Manmohan Singh as the finance minister started India’s reform process. On July 24, 1991, he backed his “then” revolutionary proposals of opening up India’s economy by paraphrasing Victor Hugo: “No power on Earth can stop an idea whose time has come.”

Good economics is also good politics. That is an idea whose time has come. Now only if Mr Singh were listening. Or should we say be allowed to listen..

(The article originally appeared at www.firstpost.com on May 24,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/petrol-bomb-is-a-dud-if-only-dr-singh-had-listened-319594.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])