Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

Even the worst governments make some right decisions. The appointment of Raghuram Govind Rajan as the next governor of the Reserve Bank of India(RBI) is one of the few correct decisions that the Congress led United Progressive Alliance(UPA) government has made in the last few years. Rajan, an alumnus of IIT Delhi, IIM Ahmedabad and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is currently the Chief Economic Advisor of the government of India.

Rajan was the Chief Economist of the International Monetary Fund(IMF) between October 2003 and December 2006. In 2003, he also won the first Fischer Black Prize, which is awarded to the most promising economist under the age of 40, by the American Finance Association. He is also a Professor of Finance at the Chicago University’s Booth School of Business.

So what can we expect from Rajan as the RBI governor? In order to understand we first need to understand what are Rajan’s views on various factors impacting the Indian economy right now, and which he will have to deal with as the governor of the RBI.

Rajan is a firm believer in the fact that high government spending in doling out various subsidies has been a major cause behind India’s high inflation. This clearly comes out in the Economic Survey for the year 2012-2013, which he was in-charge of as the Chief Economic Advisor.

A part of the summary to the first chapter State of the Economy and Prospects reads “With the subsidies bill, particularly that of petroleum products, increasing, the danger that fiscal targets would be breached substantially became very real in the current year. The situation warranted urgent steps to reduce government spending so as to contain inflation.”

This is something that he reiterated in a recent column as well, where he wrote “India needs less consumption and higher savings. The government has taken a first step by tightening its own budget and spending less, especially on distortionary subsidies.”

The RBI under D Subbarao has been very critical of the high government expenditure distorting the Indian economy. Rajan’s thinking on that front doesn’t seem to be much different from that of his predecessor.

Also Rajan firmly believes that Indian households need stronger incentives in the form of lower inflation to increase financial savings, which have been declining for a while. As the recent RBI financial stability report points out “Financial savings of households…have declined from 11.6 per cent of GDP to 8 per cent of GDP over the corresponding period (i.e. between 2007-08 to 2011-12.”

Financial savings are essentially in the form of bank deposits, life insurance, pension and provision funds, shares and debentures etc. In fact between 2010-2011 and 2011-2012, the household financial savings fell by a massive Rs 90,000 crore. This has largely been on account of high inflation. Savings have been diverted into real estate and gold in the hope of earnings returns higher than the prevailing inflation.

Also people have been saving lesser as their expenditure has gone up due to high inflation. And the financial savings will only go up, if inflation comes down, pushing up the real returns on bank fixed deposits.

“Households also need stronger incentives to increase financial savings. New fixed-income instruments, such as inflation-indexed bonds, will help. So will lower inflation, which raises real returns on bank deposits. Lower government spending, together with tight monetary policy, are contributing to greater price stability,” wrote Rajan in his column.

Given this, the focus of the RBI on controlling ‘inflation’ which continues to be close to double digits (consumer price inflation was at 9.87% in the month of June, 2013) is likely to continue under Rajan as well. Hence, the repo rate, which is the rate at which RBI lends to banks, is unlikely to come down dramatically any time soon.

Lower inflation leading to higher savings will also help in bringing down the high current account, deficit feels Rajan. During the period of twelve months ending December 31, 2012, the current account deficit of India had stood at $93 billion. In absolute terms this was only second to the United States.

The current account deficit(CAD) is the difference between total value of imports and the sum of the total value of its exports and net foreign remittances. Since imports are higher than exports and foreign remittances, the country is spending more than saving.

As Rajan told the India Brand Equity Foundation in an interview “CAD essentially reflects the fact that you are spending more than you are saving. That’s technically the definition of the CAD, which means that you need to borrow from abroad to finance your investment. Ideally, the way you would reduce your current account deficit is by saving more, which means consuming less, buying fewer goods from abroad and importing less. Or, the other way is by investing less, because that would allow you to bridge the CAD. Now we don’t want to invest less. We have enormous investment needs. So ideally, what we want to do is save more.”

And to achieve this “the first way is for the government to cut its under-saving or its deficit and that is part of what we are doing” “The second way is when the public decides to save more rather than spend. We need to encourage financial saving,” Rajan said in the interview.

Given this, Rajan has never been a great fan of subsidies and he looks at them as a short term necessity. In an interview I did with him after the release of his book Fault Lines – How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy, for the Daily News and Analysis(DNA), I had asked him whether India could afford to be a welfare state, to which he had replied “Not at the level that politicians want it to. For example, the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS), if appropriately done, is a short term insurance fix and reduces some of the pressure on the system, which is not a bad thing. But if it comes in the way of the creation of long term capabilities, and if we think NREGS is the answer to the problem of rural stagnation, we have a problem. It’s a short-term necessity in some areas. But the longer term fix has to be to open up the rural areas, connect them, education, capacity building, that is the key.”

This commitment came out in the Economic Survey as well. “The crucial lesson that emerges from the fiscal outcome in 2011-12 and 2012-13 is that in times of heightened uncertainties, there is need for continued risk assessment through close monitoring and for taking appropriate measures for achieving better fiscal marksmanship. Open ended commitments such as uncapped subsidies are particularly problematic for fiscal credibility because they expose fiscal marksmanship to the vagaries of prices,” the Survey authored under the guidance of Rajan pointed out.

So what this clearly tells us that Rajan is clearly not a jhollawallah. The last thing this country needs at this point of time is an RBI governor who is a jhollawallah.

Another important issue that Rajan will have to tackle is the rapidly depreciating rupee against the dollar. RBI’s attempts to control the value of the rupee against the dollar haven’t had much of an impact in the recent past. On this Rajan has an interesting view. As he said in an interview to the television channel ET Now “When we have capital either coming in or flowing out, sometimes it is very costly standing in the way. We would rather wait till our actions have the most impact. It would wait till the moment of maximum advantage and then use all the firepower that it has to pushback.”

What this means is that under Rajan the RBI won’t try to defend the rupee all the time. Given this, the rupee might even be allowed to fall further. What Rajan does on this front will become clear in the months to come, but this will be his biggest immediate challenge.

Another factor working in Rajan’s favour is that this is clearly not Rajan’s last job. He is still not 50. Also, he has a job at the University of Chicago, which he can always go back to.

Given this, it is unlikely that he will make any compromises to help the politicians who have appointed him and is likely to make decisions that are best suited for the Indian economy, rather than help him win brownie points with politicians.

For anyone who has any doubts on this front it is worth repeating something that happened in 2005. Every year the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, one of the twelve Federal Reserve Banks in the United States, organises a symposium at Jackson Hole in the state of Wyoming.

The conference of 2005 was to be the last conference attended by Alan Greenspan, the then Chairman of the Federal Reserve of United States, the American central bank.

Hence, the theme for the conference was the legacy of the Greenspan era. Rajan was attending the conference and presenting a paper titled “Has Financial Development Made the World Riskier?”

Those were the days when the United States was in the midst of a huge real estate bubble. The prevailing economic view was that the US had entered an era of unmatched economic prosperity and Alan Greenspan was largely responsible for it.

In a sense the conference was supposed to be a farewell for Greenspan and people were meant to say nice things about him. And that’s what almost every economist who attended the conference did, except for Rajan.

In his speech Rajan said that the era of easy money would get over soon and would not last forever as the conventional wisdom expected it to. “The bottom line is that banks are certainly not any less risky than the past despite their better capitalization, and may well be riskier. Moreover, banks now bear only the tip of the iceberg of financial sector risks…the interbank market could freeze up, and one could well have a full-blown financial crisis,” said Rajan.

In the last paragraph of his speech Rajan said it is at such times that “excesses typically build up. One source of concern is housing prices that are at elevated levels around the globe.”

Rajan’s speech did not go down well with people at the conference. This is not what they wanted to hear. He was essentially saying that the Greenspan era was hardly what it was being made out to be.

Given this, Rajan came in for heavy criticism. As he recounts in his book Fault Lines – How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy: “Forecasting at that time did not require tremendous prescience: all I did was connect the dots… I did not, however, foresee the reaction from the normally polite conference audience. I exaggerate only a bit when I say I felt like an early Christian who had wandered into a convention of half-starved lions. As I walked away from the podium after being roundly criticized by a number of luminaries (with a few notable exceptions), I felt some unease. It was not caused by the criticism itself…Rather it was because the critics seemed to be ignoring what going on before their eyes.”

The criticism notwithstanding Rajan turned out right in the end. And what was interesting that he called it as he saw it. India needs the same honesty from Rajan, as and when he takes over as the next RBI governor.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 6, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Repo Rate

Why RBI killed the debt fund

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

The Reserve Bank of India(RBI) is doing everything that it can do to stop the rupee from falling against the dollar. Yesterday it announced further measures on that front.

Each bank will now be allowed to borrow only upto 0.5% of its deposits from the RBI at the repo rate. Repo rate is the interest rate at which RBI lends to banks in the short term and it currently stands at 7.25%.

Sometime back the RBI had put an overall limit of Rs 75,000 crore, on the amount of money that banks could borrow from it, at the repo rate. This facility of banks borrowing from the RBI at the repo rate is referred to as the liquidity adjustment facility.

The limit of Rs 75,000 crore worked out to around 1% of total deposits of all banks. Now the borrowing limit has been set at an individual bank level. And each bank cannot borrow more than 0.5% of its deposits from the RBI at the repo rate. This move by the RBI is expected bring down the total quantum of funds available to all banks to Rs 37,000 crore, reports The Economic Times.

In another move the RBI tweaked the amount of money that banks need to maintain as a cash reserve ratio(CRR) on a daily basis. Banks currently need to maintain a CRR of 4% i.e. for every Rs 100 of deposits that the banks have, Rs 4 needs to set aside with the RBI.

Currently the banks need to maintain an average CRR of 4% over a reporting fortnight. On a daily basis this number may vary and can even dip under 4% on some days. So the banks need not maintain a CRR of Rs 4 with the RBI for every Rs 100 of deposits they have, on every day.

They are allowed to maintain a CRR of as low as Rs 2.80 (i.e. 70% of 4%) for every Rs 100 of deposits they have. Of course, this means that on other days, the banks will have to maintain a higher CRR, so as to average 4% over the reporting fortnight.

This gives the banks some amount of flexibility. Money put aside to maintain the CRR does not earn any interest. Hence, if on any given day if the bank is short of funds, it can always run down its CRR instead of borrowing money.

But the RBI has now taken away that flexibility. Effective from July 27, 2013, banks will be required to maintain a minimum daily CRR balance of 99 per cent of the requirement. This means that on any given day the banks need to maintain a CRR of Rs 3.96 (99% of 4%) for every Rs 100 of deposits they have. This number could have earlier fallen to Rs 2.80 for every Rs 100 of deposits. The Economic Times reports that this move is expected to suck out Rs 90,000 crore from the financial system.

With so much money being sucked out of the financial system the idea is to make rupee scarce and hence help increase its value against the dollar. As I write this the rupee is worth 59.24 to a dollar. It had closed at 59.76 to a dollar yesterday. So RBI’s moves have had some impact in the short term, or the chances are that the rupee might have crossed 60 to a dollar again today.

But there are side effects to this as well. Banks can now borrow only a limited amount of money from the RBI under the liquidity adjustment facility at the repo rate of 7.25%. If they have to borrow money beyond that they need to borrow it at the marginal standing facility rate which is at 10.25%. This is three hundred basis points(one basis point is equal to one hundredth of a percentage) higher than the repo rate at 10.25%. Given that, the banks can borrow only a limited amount of money from the RBI at the repo rate. Hence, the marginal standing facility rate has effectively become the repo rate.

As Pratip Chaudhuri, chairman of State Bank of India told Business Standard “Effectively, the repo rate becomes the marginal standing facility rate, and we have to adjust to this new rate regime. The steps show the central bank wants to stabilise the rupee.”

All this suggests an environment of “tight liquidity” in the Indian financial system. What this also means is that instead of borrowing from the RBI at a significantly higher 10.25%, the banks may sell out on the government bonds they have invested in, whenever they need hard cash.

When many banks and financial institutions sell bonds at the same time, bond prices fall. When bond prices fall, the return or yield, for those who bought the bonds at lower prices, goes up. This is because the amount of interest that is paid on these bonds by the government continues to be the same.

And that is precisely what happened today. The return on the 10 year Indian government bond has risen by a whopping 33 basis points to 8.5%. Returns on other bonds have also jumped.

Debt mutual funds which invest in various kinds of bonds have been severely impacted by the recent moves of the RBI. Since bond prices have fallen, debt mutual funds which invest in these bonds have faced significant losses.

In fact, the data for the kind of losses that debt mutual funds will face today, will only become available by late evening. But their performance has been disastrous over the last one month. And things should be no different today.

Many debt funds have lost as much as 5% over the last one month. And these are funds which give investors a return of 8-10% over a period of one year. So RBI has effectively killed the debt fund investors in India.

But then there was nothing else that it could really do. The RBI has been trying to manage one side of the rupee dollar equation. It has been trying to make rupee scarce by sucking it out of the financial system.

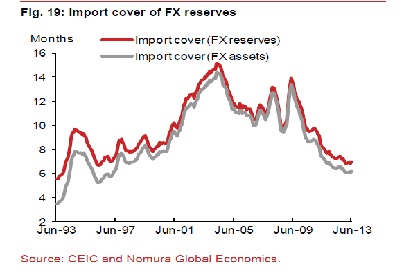

The other thing that it could possibly do is to sell dollars and buy rupees. This will lead to there being enough dollars in the market and thus the rupee will not lose value against the dollar. The trouble is that the RBI has only so many dollars and it cannot create them out of thin air (which it can do with rupees). As the following graph tells us very clearly, India does not have enough foreign exchange reserves in comparison to its imports.

The ratio of foreign exchange reserves divided by imports is a little over six. What this means is that India’s total foreign exchange reserves as of now are good enough to pay for imports of around a little over six months. This is a precarious situation to be in and was only last seen in the 1990s, as is clear from the graph.

The government may be clamping down on gold imports but there are other imports it really doesn’t have much control on. “The commodity intensity of imports is high,” write analysts of Nomura Financial Advisory and Securities in a report titled India: Turbulent Times Ahead. This is because India imports a lot of coal, oil, gas, fertilizer and edible oil. And there is no way that the government can clamp down on the import of these commodities, which are an everyday necessity. Given this, India will continue to need a lot of dollars to import these commodities.

Hence, RBI is not in a situation to sell dollars to control the value of the rupee. So, it has had to resort to taking steps that make the rupee scarce in the financial system.

The trouble is that this has severe negative repercussions on other fronts. Debt fund investors are now reeling under heavy losses. Also, the return on the 10 year bonds has gone up. This means that other borrowers will have to pay higher interest on their loans. Lending to the government is deemed to be the safest form of lending. Given this, returns on other loans need to be higher than the return on lending to the government, to compensate for the greater amount of risk. And this means higher interest rates.

The finance minister P Chidambaram has been calling for lower interest rates to revive economic growth. But he is not going to get them any time soon. The mess is getting messier.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on July 24, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Why RBI is in a Catch 22 situation when it comes to the rupee

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) will carry out an open market operation and sell government of India bonds worth Rs 12,000 crore today i.e. July 18,2013.

The RBI carries out an open market operation in order to suck out or put in rupees into the financial system. When the RBI needs to suck out rupees from the system it sells government of India bonds, like it is doing today.

Banks and other financial institutions buy these bonds and pay the RBI in rupees, and thus the RBI sucks out rupees from the market.

The rupee has had a tough time against the US dollar lately and had recently touched an all time low of 61.23 to a dollar. By selling bonds, the RBI wants to suck out rupees from the financial system and thus try and ensure that rupee gains value against the dollar.

The RBI has been trying to defend the value of the rupee against the dollar by selling dollars from the foreign exchange reserves that it has. When the RBI sells dollars it leads to a surfeit of dollars in the market and as a result the dollar loses value against the rupee or at least the rupee does not fall as fast as it otherwise would have.

The trouble is that the RBI does not have an unlimited supply of dollars. Unlike the Federal Reserve of United States, the RBI cannot create dollars out of thin air by printing them. In the period of three weeks ending July 5, 2013, as the RBI sold dollars to defend the rupee, the foreign exchange reserves fell by $10.5 billion to $280.17 billion.

At this level India has foreign exchange reserves that are enough to cover around 6.3 months worth of imports. Such low levels of foreign exchange expressed as import cover hasn’t been seen since the early 1990s. Given this, there isn’t much scope for the RBI to sell dollars and hope to control the value of the rupee. It simply doesn’t have enough dollars going around.

Hence, it is trying to control the other end of the equation. It cannot ensure that there are enough dollars going around in the market, so its trying to create a shortage of rupees, by selling government of India bonds.

In fact, as a part of this plan the RBI has also put an overall limit of Rs 75,000 crore, on the amount of money banks can borrow from it, at the repo rate of 7.25%. Repo rate is the interest rate at which RBI lends money to banks in the short term.

Banks can borrow money beyond this limit at what is known as the marginal standing facility rate. This rate has been raised by 200 basis points(one basis point is one hundredth of a percentage) to 10.25%. Hence, borrowing from the RBI has been made more expensive.

A major motive behind this move was to rein in the speculators. As Jehangir Aziz of JP Morgan Chase wrote in The Indian Express “It has been ridiculously cheap over the last month to borrow rupees at the overnight rate, buy dollars and then wait for the exchange rate to crumble. In June, the monthly overnight interest rate was 0.5 per cent and the depreciation 10 per cent.”

Lets understand this through an example. Lets say a speculator borrows Rs 54,000 at a monthly interest rate of 0.5%. This is at a point of time when one dollar is worth Rs 54. He uses this money to buy dollars and ends up buying $1000 (Rs 54,000/54). When he sells rupees to buy dollars it puts pressure on the value of the rupee against the dollar.

After buying dollars, the speculator just sits on it for a month, by the time rupee has depreciated 10% against the dollar and one dollar is worth Rs 59.4(Rs 54 + 10% of Rs 54). He sells the dollars, and gets Rs 59,400($1000 x 60) in return. He needs to repay Rs 54,000 plus a 0.5% interest on it. The rest is profit. This is how speculators had been making money for sometime and thus putting pressure on the rupee.

By making it more expensive to borrow, the RBI hopes to control the speculation and thus ensure that there is lesser pressure on the rupee.

The message that the market seems to have taken from the efforts of the RBI to create a scarcity of rupees is that interest rates are on their way up. The hope is that at higher interest rates foreign investors will bring in more dollars and convert them into rupees and buy Indian bonds. Foreign investors have sold off bonds worth $8.4 billion since their peak so far this year.

When foreign investors sell bonds they get paid in rupees. They sell these rupees and buy dollars to repatriate the money. This puts pressure on the rupee and it loses value against the dollar. The assumption is that at a higher rate of interest the foreign investors might want to invest in Indian bonds and bring in more dollars to do so. This strategy of defending a currency is referred to as the classic interest rate defence and has been practised by both Brazil as well Indonesia in the recent past.

But there are other problems with this approach. Rising interest rates are not good news for economic growth as people are less likely to borrow and spend, when they have to pay higher EMIs. A spate of foreign brokerages have cut their GDP growth forecasts for India for this financial year (i.e. the period between April 1, 2013 and March 31, 2014). Also sectors like banking, auto and real estate are looking even more unattractive in the background of interest rates going up. In fact, auto and banking sectors were anyway down in the dumps.

Slower economic growth could lead to foreign investors selling out of the stock market. When foreign investors sell stocks they get paid in rupees. In order to repatriate this money the foreign investors sell these rupees and buy dollars. And if this situation were to arise, it could put further pressure on the rupee.

Hence by doing what it has done the RBI has put itself in a Catch 22 situation. But then did it really have any other option? The other big question is whether the politicians who actually run the Congress led UPA government will be ready to accept slow economic growth(not that the economy is currently on steroids) so close to the next Lok Sabha elections? On that your guess is as good as mine.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on July 18, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

RBI may cut rates, but your loan rates may not fall

Vivek Kaul

The monetary policy review of the Reserve Bank of India(RBI) is scheduled for March 19,2013 i.e. tomorrow. Every time the top brass of the RBI is supposed to meet, calls for an interest rate cut are made. In fact, there seems to be a formula that has evolved to create pressure on the RBI to cut the repo rate. The repo rate is the interest rate at which RBI lends to banks.

The formula includes the finance minister P Chidambaram giving statements in the media about there being enough room for the RBI to cut interest rates. “There is a case for the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to cut policy rates, and the central bank should take comfort from the government’s efforts to cut the fiscal deficit,” Chidambaram told the Bloomberg television channel today.

Other than Chidambram, an economist close to the Prime Minister Manmohan Singh also gives out similar statements. “The budget has also gone a long way in containing the fiscal deficit, both in the current year and in the following year, and played its role in containing demand pressures in the system. Therefore, in some sense there is greater space for monetary policy now to act in the direction of stimulating growth,” C Rangarajan, former RBI governor, who now heads the prime minister’s economic advisory council, told The Economic Times. What Rangarajan meant in simple English was that conditions were ideal for the RBI to cut interest rates.

And then there are bankers (most those running public sector banks) perpetually egging the RBI to cut interest rates. As an NDTV storypoints out “A majority of bankers polled by NDTV expect the Reserve Bank to cut interest rates in the policy review due on Tuesday. 85 per cent bankers polled by NDTV said the central bank is likely to cut repo rates.”

Corporates always want lower interest rates and they say that clearly. As a recent Business Standard story pointed out “An interest rate cut, at a time when demand was not showing any sign of revival, would boost sentiments, especially for interest-rate sensitives like the car and real estate sectors, which had been showing negative growth, a majority of the 15 CEOs polled by Business Standard said.”

So everyone wants lower interest rates. The finance minister. The prime minister. The banks. And the corporates.

Lower interest rates will create economic growth is the simple logic. Once the RBI cuts the repo rate, the banks will also pass on the cut to their borrowers. At lower interest rates people will borrow more. They will buy more homes, cars, two wheelers, consumer durables and so on. This will help the companies which sell these things. Car sales were down by more than 25% in the month of February. Lower interest rates will improve car sales. All this borrowing and spending will revive the economic growth and the economy will grow at higher rate instead of the 4.5% it grew at between October and December, 2012.

And that’s the formula. Those who believe in the formula also like to believe that everything else is in place. The only thing that is missing is lower interest rates. And that can only come about once the RBI starts cutting interest rates.

So the question is will the RBI governor D Subbarao oblige? He may. He may not. But the real answer to the question is, it doesn’t really matter.

Repo rate at best is a signal from the RBI to banks. When it cuts the repo rate it is sending out a signal to the banks that it expects interest rates to come down in the days to come. Now it is up to the banks whether they want to take that signal or not.

When everyone talks about lower interest rates, they basically talk about lower interest rates on loans that banks give out. Now banks can give out loans at lower interest rates only when they can raise deposits at lower interest rates. Banks can raise deposits at lower interest rates when there is enough liquidity in the system i.e. people have enough money going around and they are willing to save that money as deposits with banks.

Lets look at some numbers. In the six month period between August 24, 2012 and February 22, 2013 (the latest data which is available from the RBI) banks raised deposits worth Rs 2,69,350 crore. During the same period they gave out loans worth Rs 3,94,090 crore. This means the incremental credit-deposit ratio in the last six months for banks has been 146%.

So for every Rs 100 that banks have borrowed as a deposit they have given out Rs 146 as a loan in the last six months. If we look at things over the last one year period, things are a little better. For every Rs 100 that banks have borrowed as a deposit, they have given out Rs 93 as a loan.

What this clearly tells us is that banks have not been able to raise enough deposits to fund their loans. For every Rs 100 that banks borrow, they need to maintain a statutory liquidity ratio of 23%. This means that for every Rs 100 that banks borrow at least Rs 23 has to be invested in government securities. These securities are issued by the government to finance its fiscal deficit. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what the government earns and what it spends.

Other than this a cash reserve ratio of 4% also needs to be maintained. This means that for every Rs 100 that is borrowed Rs 4 needs to be maintained as a reserve with the RBI. So for every Rs 100 that is borrowed by the banks, Rs 27 (Rs 23 + Rs 4) is taken out of the equation immediately. Hence only the remaining Rs 73 (Rs 100 – Rs 27) can be lent. This means that in an ideal scenario the credit deposit ratio of a bank cannot be more than 73%. But over the last six months its been double of that at 146% i.e. banks have loaned out Rs 146 for every Rs 100 that they have raised as a deposit.

So how have banks been financing these loans? This has been done through the extra investments (greater than the required 23%) that banks have had in government securities. Banks are selling these government securities and using that money to finance loans beyond deposits.

The broader point is that banks haven’t been able to raise enough deposits to keep financing the loans they have been giving out. And in that scenario you can’t expect them to cut interest rates on their deposits. If they can’t cut interest rates on their deposits, how will they cut interest rates on their loans?

The other point that both Chidambaram and Rangarajan harped on was the government’s effort to cut/control the fiscal deficit. The fiscal deficit for the current financial year (i.e. the period between April 1, 2012 and March 31,2013) had been targeted at Rs 5,13,590 crore. The final number is expected to come at Rs 5,20,925 crore. So where is the cut/control that Chidambaram and Rangarajan seem to be talking about? Yes, the situation could have been much worse. But simply because the situation did not turn out to be much worse doesn’t mean that it has improved.

The fiscal deficit target for the next financial year (i.e. the period between April 1, 2013 and March 31, 2014) is at Rs 5,42,499 crore. Again, this is higher than the number last year.

When the government borrows more it “crowds out” and leaves a lower amount of savings for the banks and other financial institutions to borrow from. This leads to higher interest rates on deposits.

What does not help the situation is the fact that household savings in India have been falling over the last few years. In the year 2009-2010 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2009 and March 31, 2010) the household savings stood at 25.2% of the GDP. In the year 2011-2012 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2011 and March 31, 2012) the household savings had fallen to 22.3% of the GDP. Even within household savings, the amount of money coming into financial savings has also been falling. As the Economic Survey that came out before the budget pointed out “Within households, the share of financial savings vis-à-vis physical savings has been declining in recent years. Financial savings take the form of bank deposits, life insurance funds, pension and provident funds, shares and debentures, etc. Financial savings accounted for around 55 per cent of total household savings during the 1990s. Their share declined to 47 per cent in the 2000-10 decade and it was 36 per cent in 2011-12. In fact, household financial savings were lower by nearly Rs 90,000 crore in 2011-12 vis-à-vis 2010-11.”

While the household savings number for the current year is not available, the broader trend in savings has been downward. In this scenario interest rates on fixed deposits cannot go down. And given that interest rate on loans cannot go down either.

Of course bankers understand this but they still make calls for the RBI cutting interest rates. In case of public sector bankers the only explanation is that they are trying to toe the government line of wanting lower interest rates.

So whatever the RBI does tomorrow, it doesn’t really matter. If it cuts the repo rate, then public sector banks will be forced to announce token cuts in their interest rates as well. Like on January 29,2013, the RBI cut its repo rate by 0.25% to 7.75%. The State Bank of India, the nation’s largest bank, followed it up with a base rate cut of 0.05% to 9.7% the very next day. Base rate is the minimum interest rate that the bank is allowed to charge its customers.

A 0.05% cut in interest rate would have probably been somebody’s idea of a joke. The irony is that the joke might be about to be repeated in a few day’s time.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on March 18,2013.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

A policy rate Catch 22

Vivek Kaul

“That’s some catch, that Catch-22,” says Yossarian, the lead character in Joseph Heller’s all time classic Catch 22. Duvvuri Subbarao, the governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is facing a Catch 22 situation currently and some catch it is.

He needs to decide whether to encourage economic growth or to control inflation. Theoretically Subbarao can encourage economic growth by cutting the interest rates. But that is likely to fuel inflation as people and companies will borrow and spend more, leading to a rise in prices.

He can control inflation by keeping the interest rates high. But that kills economic growth as businesses don’t borrow money to expand and people go slow on taking loans for purchasing cars, motorcycles, homes and consumer durables. This hurts businesses and slows down economic growth.

The RBI seems to be trying to control inflation by keeping the interest rates high rather than try and encourage economic growth by cutting the interest rate. In the first quarter review of monetary policy 2012-2013 which was released on July 31, 2012, the RBI decided to keep the repo rate at 8%. Repo rate is the interest rate at which the RBI lends to banks.

By keeping the repo rate high the RBI hopes to control inflation. “The primary focus of monetary policy remains inflation control,” the RBI said in a statement. But economic theory and practice don’t always go together.

The inflation in India is primarily on account of rising oil prices and food prices. Oil is a commodity that is bought and sold internationally and the RBI cannot control its price. The price of oil has been falling since the beginning of this year but it has started to inch its way back up and as I write this, brent crude oil is quoting at $105per barrel. While the government has shielded the people from a rise in oil price by not raising the price of diesel, LPG and kerosene, petrol prices have been raised.

As far as food is concerned there seems to be a structural shift happening. “The stickiness in inflation…was largely on account of high primary food inflation…due to an unusual spike in vegetable prices and sustained high inflation in protein items,” the RBI said.

Protein items primarily include various kinds of pulses, milk and other dairy items. The various social schemes being run by the current United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government have put more money into the hands of rural India. One thing that seems to have happened because of this is that people are eating better than before.

Economic theory suggests that once income levels rise above $1000 per annum, a major portion of the increased income is spent on more food and better quality food. Also people shift from cereal based diets to protein based diets. In large parts of the world this means an increase in the consumption of meat. But in India it means more consumption of milk and pulses. Again this is something that the RBI has no control over. As long as the UPA keeps running its social schemes this phenomenon of increased food prices is likely to continue.

What does not help in the near term is a deficient monsoon. Rainfall upto July 25,2012 has been 22% below its long period average. This means food prices will continue to rise.

What this clearly tells us is that RBI is not in a position to control inflation as it stands today. So should it be cutting the repo rate and in the process encouraging economic growth?

When RBI cuts the repo rate it is essentially giving a signal to banks that it expects the interest rates to go down in the days to come. But it is upto the banks to decide whether they take that signal seriously. When the RBI cut the repo rate by 50 basis points (one basis point is one hundredth of a percentage point) in April, the banks cut their interest rates by only 25 basis points on an average.

The reason was the increased borrowing by the government to finance its growing fiscal deficit. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what the government earns and what it spends. Between 2007 and 2012 the fiscal deficit of the government has gone up by more than 300%. During the same period its income has increased by just 36%.

The fiscal deficit has been growing on account of various subsidies like oil, food and fertizlier being offered by the government. “During April-May 2012, while food subsidies were lower, fertiliser subsidies were more than twice the previous year’s level,” the RBI statement pointed out. What also does not help is the fact that the Rs 43,580 crore oil subsidy budgeted for this year has already run out. The government compensates the oil marketing companies (OMCs) for selling kerosene, diesel and LPG at below cost. With oil prices over $100 again, the oil subsidies are likely to increase in the days to come.

This means increased borrowing by the government to compensate the OMCs for their losses. Increased borrowing by the government will mean that banks will have a lower pool of money to borrow from and hence they will have to continue to offer high interest rates on their deposits and charge high interest rates on their loans.

So what is the way out? “Clearly, if the target of restricting the expenditure on subsidies to under 2 per cent of GDP in 2012-13, as set out in the Union Budget, is to be achieved, immediate action on fuel and fertiliser subsidies will be required,” the RBI said.

But raising prices is easier said than done. Another theory being bandied around is that Duvvuri Subbarao is Chiddu’s baby (P Chidambaram, the Home Minister) and he will start cutting the repo rate as soon as Chidambaram is back at the Finance Ministry.

(The article originally appeared in the Asian Age/Deccan Chronicle on August 1,2012. http://www.asianage.com/columnists/policy-rate-catch-22-677)

The article was written before P Chidambaram was appointed as the Finance Minister

(Vivek Kaul is a Mumbai based writer and can be reached at [email protected])