Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

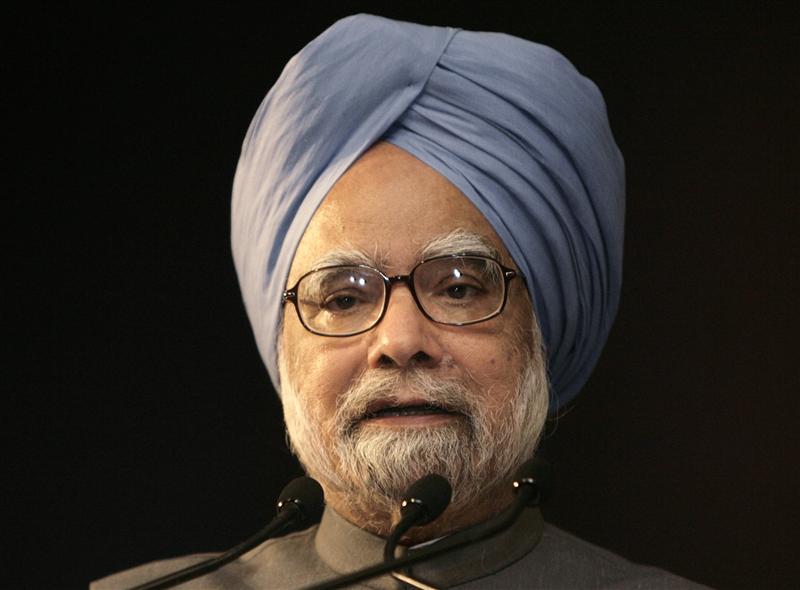

“It is a combination of youth and experience,” said Prime Minister Manmohan Singh after reshuffling his ministers yesterday. The reshuffle saw 17 new faces become ministers.

The average age of the 17 new ministers is 52.4 years, with the youngest Sachin Pilot having turned 35 in September this year, and the oldest Abu Hasem Khan Chowdhury will turn 75 in early January next year. Also Pilot is the only minister who is less than 40 years of age.

So the question is where is the youth that Manmohan Singh was talking about? Unless of course Dr Singh was referring to the old Bob Dylan number that went somewhat like this.

May God bless and keep you always

May your wishes all come true

May you always do for others

And let others do for you

May you build a ladder to the stars

And climb on every rung

May you stay forever young

Forever young, forever young

May you stay forever young

The bigger question though is does the Congress have young leaders who are not hereditary leaders i.e. they are in politics because their fathers and grandfathers were also in politics.

Sachin Pilot is the son of Rajesh Pilot who was a formidable Congress leader till he died in a car crash. He also happens to the son-in-law of Dr Farooq Abdullah, the Jammu and Kashmir strongman. His brother in law Omar is the current chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir.

The other so called young gun to be inducted as a minister is Jyotiraditya Scindia. He will turn 42 on January 1, 2013. He comes from a royal family and his grandmother Vijayaraje Scindia and father Madhavrao Scindia were both career politicians.

Patrick French in his book India: A Portrait released in early 2011 carried out a very interesting piece of research. As he pointed out “Every MP in the Lok Sabha under the age of 30 had in effect inherited a seat, and more than two-thirds of the 66 MPs aged 40 or under were hereditary MPs… Of the 38 youngest MPs, 33 had arrived with the help of mummy-daddy. Of the remaining five, one was Meenakshi Natarajan, the biochem graduate who had been hand-picked by Rahul, three appeared to be self-made politicians who had made it up the ranks of the BJP, BSP and CPI(M) respectively, and the fifth was a Lucknow University mafioso who had been taken on board by Mayawati: he was a “history-sheeter”—meaning numerous criminal chargesheets had been laid against him—who had been involved in shootouts and charged four times under the Gangsters Act.”

Of course the babalog also tend to start earlier than the ones who make it on their own. As French writes “In addition, this new wave of Indian lawmakers would have a decade’s advantage in politics over their peers, since the average MP who had benefited from family politics was almost 10 years younger than those who had arrived with ‘No Significant Family Background’… The average age of an MP with no significant family background was 58; for a hereditary MP it was 48.”

This trend is even more extreme in the Congress Party. “In the Congress, the situation was yet more extreme: every Congress MP under the age of 35 was a hereditary MP,” writes French.

So the point is that the Congress Party in particular and the Indian Parliament in general doesn’t have many young leaders who have made it on their own.

And if some recent biographies of Rahul Gandhi and some not recent ones of Sonia Gandhi are to be believed, this is the reason Rahul has stayed away from the government. He is trying to build internal democracy within the Congress party, so that a new genuine crop of younger leaders comes up.

As French writes quoting Rahul Gandhi “There are three-four ways of entering politics,” he said frankly to a gathering of students in Madhya Pradesh. “First, if one has money and power. Second, through family connections. I am an example of that. Third, if one knows somebody in politics. And fourth, by working hard for the people.” Unlike many of the other young hereditary MPs, he did not pretend otherwise. “Main apne pita, nani aur pardada ke bina us jagah par nahin pahunch sakta tha jahan main aaj hoon(Without my father, grandmother and great-grandfather, I could never have been in the place that I am now.)” This can be aptly titled the Rahul Gandhi syndrome.

Rahul Gandhi wants to set this right within the Congress and is thus trying to build an internal democratic structure within the Youth Congress and the National Students Union of India. As Aarthi Ramachandran writes in Decoding Rahul Gandhi “The Youth Congress decided it was ready to hold its first internal elections in mid-2008. The process was handled by an independent NGO, Foundation for Advanced Management of Elections (FAME), started by former election commissioners K J Rao, James Lyndogh N Gopalswami and T S Krishnamurthy.”

The first such election was held in Punjab. And what was the result? “Not everything went according to plan. Though Rahul himself camped in Amritsar to make sure the election lived up to the expectations of being the first free and fair one, the old Congress reared its head through the process. Ravneet Singh ‘Bittu’, the grandson of former Congress Chief minister, Beant Singh, became the first elected Punjab Youth Congress president. He had the backing of the former chief minister of Punjab, Captain Amrinder Singh. This raised questions about whether the elections had indeed ushered in internal democracy,” writes Ramachandran. Bittu when he was elected was 33.

This is a worrying trend. And even plays out in the context of elected women MPs in the Congress Party. As French writes “The Congress presently had 208 MPs, of whom 23 were women. This was the same as average, 11 per cent. So far so low; now comes the difference: 19 out of the 23 Congress women MPs were hereditary (and of these, four were hyperhereditary). This left only four Congress women MPs who appeared to have reached Parliament on their own merit: Meenakshi Natarajan, Annu Tandon, and two other stalwarts. Who were they? Dr Girija Vyas, the president of the National Commission for Women, and Chandresh Kumari Katoch, who turned out to be hereditary by another measure, being the daughter of Hanwant Singh, the maharaja of Jodhpur.”

Entry into politics in India has become like a family owned business where the sons(and now daughters) are destined to takeover irrespective of the fact whether they have the aptitude for the job or not. French puts it best when he says “If the trend continued, it was possible that most members of the Indian Parliament would be there by heredity alone, and the nation would be back to where it had started before the freedom struggle, with rule by a hereditary monarch and assorted Indian princelings.”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on October 29,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/politics/every-young-minister-in-new-look-upa-govt-is-a-dynast-506497.html#disqus_thread

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

Rahul Gandhi

Rahul: Reluctant politician who was once afraid of the dark

When Rahul Gandhi was young he was afraid of the dark. He felt that darkness held ghosts and bad things. His grandmother Indira Gandhi helped him overcome that fear. As Aarthi Ramachandran writes in Decoding Rahul Gandhi “Speaking to young children at the opening of a science fair at a Delhi school in November 201 he(i.e. Rahul) told them how he was scared of darkness when he was young as he felt it held “ghosts” and “bad things”. Then, he said, one day his grandmother had asked him why he didn’t go and see himself what was inside the darkness. So, he had walked into the garden in the dark and he had kept walking and then realised suddenly that ‘there was nothing there in the darkness to be scared of’.” And thus Rahul overcame the fear of darkness and ghosts.

When Rahul Gandhi was young he was afraid of the dark. He felt that darkness held ghosts and bad things. His grandmother Indira Gandhi helped him overcome that fear. As Aarthi Ramachandran writes in Decoding Rahul Gandhi “Speaking to young children at the opening of a science fair at a Delhi school in November 201 he(i.e. Rahul) told them how he was scared of darkness when he was young as he felt it held “ghosts” and “bad things”. Then, he said, one day his grandmother had asked him why he didn’t go and see himself what was inside the darkness. So, he had walked into the garden in the dark and he had kept walking and then realised suddenly that ‘there was nothing there in the darkness to be scared of’.” And thus Rahul overcame the fear of darkness and ghosts.

The life of Rahul Gandhi has largely been a mystery for India and Indians. Where was he educated? Where did he work before joining politic full time? What are his views on various things? What does he think about the current state of the Indian economy? What does he think of the government which his mother Sonia runs through the remote control? Does he have a girl friend? When does he plan to marry? Why hasn’t he given any interviews to the media since 2005?

These are questions both personal and professional that Indians would love to have answers for. Aarthi Ramachandran answers some of these questions in her new book Decoding Rahul Gandhi.

After the assassination of Indira Gandhi, both Rahul and his sister Priyanka were largely taught at home. Ramachandran quotes out of Sonia Gandhi’s book Rajiv: ““The day of my mother-in-law’s assassination was the last day Rahul and Priyanka ever attended school…For the next five years the children remained at home, studying with tutors, virtually imprisoned. The only space outside our four walls where they could step without cordon of security was our garden,” Sonia wrote.”

Rahul is a year and a half older to his sister Priyanka and was a student of the St Columba’s school before the assassination of his grandmother. But both Rahul and Priyanka ended up in the same class despite their age difference. “Rahul’s education was disrupted due to that incident (Indira Gandhi’s assassination) and he dropped a year of school, possibly the same year that Indira died. Rajiv was asked how both Rahul and Priyanka were in the same class during an interview in 1988. “Only one year separates them. And with all the shifting, they came to be in the same class. But that has one advantage: they can be taught each subject by the same tutor. Now, we can’t possibly keep separate tutors for each of them, that would be too expensive,” he quipped – both children were being home tutored,” writes Ramachandran.

Rahul joined Delhi’s St Stephens College in 1989 to study history. He got admission under the sports quota. And there was a lot of controversy surrounding his admission. As Ramachandran points out “When Rahul entered Delhi’s prestigious St. Stephen’s College in 1989 after finishing his schooling, the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) claimed his admission, under the sports quota for his skills in rifle shooting, was invalid. The allegation appeared to be that with 61 per cent marks in his school-leaving examinations, Rahul was not academically bright enough to enter the college. The BJP’s Delhi chief at that time, Madam Lal Khurana, claimed that Rahul’s certificates in shooting were fake.” The National Rifle Association came to Rahul’s rescue issuing a statement in his favour about his ability as a rifle shooter. During Rahul’s time at Stephens 20-25 special protection group (SPG) guards would be all over the college with sling bags which supposedly had guns.

After a year at Stephens, Rahul left for Harvard. There is very little clarity on the period he was at Harvard or the subjects he studied there. “It has been widely reported in the Indian media and some foreign publications that Rahul took courses in economics at Harvard,” writes Ramachandran. “Neither Rahul nor Harvard officials have confirmed this. Rahul did not respond to questions about this course of study and the time period he was at Harvard….Harvard too said it could not disclose details about Rahul Gandhi’s time at Harvard.”

Though Harvard did confirm that Rahul was a student without getting into the specifics of the time period or the courses he attended. In May 1991 Rahul’s father, Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated. This compelled him to take a transfer to Rollins College in Florida and from here graduated with a BA in 1994. The website of the college lists him as alumnus who graduated in International Relations.

After this, Rahul went to get an MPhil in developmental studies from the Cambridge University, in the United Kingdom. There has been some controversy surrounding this as well. “In the run up to the 2009 general elections…The New Indian Express alleged that Rahul had not only got the name of his course wrong but also the year. The paper said he had attended the course only in 2004-05. It produced a certificate from the university as evidence of its claim. Rahul…sent a notice to the newspaper….With the notice was a letter issued by Cambridge University…in which its vice chancellor…clarified that Rahul was a student at Trinity College from October 1994 to July 1995. She also said that he was awarded MPhil in developmental studies in 1995,” writes Ramachandran.

What comes across here is a reluctance on part of Rahul to be open about his educational qualifications. As the author explains “Rahul’s unwillingness to be open about his educational background is similar to Gandhi family’s secrecy over Sonia Gandhi’s illness. Sonia and her family have been resolute in their silence on her medical condition despite speculation…that she is suffering from some kind of cancer…It can be argued that her health is a matter of public interest given that she is the de factor head of the Congress-led coalition government…In the same way Rahul Gandhi’s educational qualifications are of the importance to the public at large as he is perceived to be a future prime ministerial candidate of the Congress and is a Member of Parliament.”

After Cambridge, Rahul Gandhi worked for three years with consulting firm Monitor in London. Strategy guru Michael Porter was one of the co-founders of the firm. Rahul was with Monitor from June 1996 to early March 1999. As Ramachandran writes “According to sources, who have known Rahul from his time at Monitor, there were no problems with his performance at the firm. He worked there under an assumed name and his colleagues did not know of his real identity, said a Monitor employee who was at the firm around the same time as Rahul. ‘His looks gave it away to those of us who knew who he could be,’ the source said.” But beyond this nothing is known about his key result areas or the sectors Rahul specialised in during his time at Monitor.

After quitting Monitor, Rahul came back to India to help his mother Sonia with the 1999 general election campaign. Once the elections were over Rahul disappeared from the political firmament. “There is no exact information about any other job Rahul might have taken up in the intervening years after he left Monitor in March 1999 and returned to India for good in late 2002,” writes Ramachandran.

During the time Rahul spent at London the media also discovered his girl friend Veronique (though they kept calling her Juanita). He was spotted with her watching an India-England cricket match at Edgbaston and holidaying with her in the Andamans at the end of 1999, and again in Kerala and Lakshdweep in 2003, for a year end family vacation.

Rahul finally cleared the mystery himself in an interview to Vrinda Gopinath of the The Indian Express during the run up to the 2004 Lok Sabha elections. As Ramachandran writes “’My girlfriend’s name is Veronique not Juanita…she is Spainish and not Venezuelan or Columbian. She is an architect not a waitress, thought I wouldn’t have had a problem with that. She is also my best friend,’ he told her…After he won from Amethi, he held a rare informal interaction with journalists in his constituency. They asked about his girlfriend’s nationality to which he replied she had been living in Venezuela for a long time although her parents were Spanish. He also said that he was not planning on getting married anytime soon.” Nothing has been heard of Veronique since 2004.

His years in consulting seem to have had a great impact on Rahul and since coming back to India in late 2002, Rahul has been trying to apply The Toyota Way on the functioning of the Congress party. The Toyota way is a series of best practices used by the Toyota Motor Company of Japan. As Ramachandran explains “The Toyota Way spoke of making decisions slowly by consensus, thoroughly considering all options and then implementing decisions rapidly…The consensus process, though time-consuming, helps broaden the search for solutions and once a decision is made, the stage is set for rapid implementation.”

Such strategic ideas are being used for the revamp and promotion of internal democracy within the Indian Youth Congress and the National Students Union of India. Processes are being built to ensure ending the role of family connections in appointments and promotions in the two organisations.

But the big question on everybody’s lips has been when will Rahul Gandhi join the government? In a controversial interview to the Tehalka magazine in September 2005, Rahul Gandhi is reported to have said that he could have become the Prime Minister at twenty-five. Abhishek Manu Singhvi the then Congress spokesperson later specifically mentioned that Rahul wanted to state that he had not said ‘I could have been prime minister at the age of twenty-five if I wanted to’. Rahul hasn’t given any interview since then.

On another occasion Rahul said that “Please do not take it as any kind of arrogance, but having seen enough prime ministers in the family…it is not such a big deal. In fact, I often wonder why should you need a post to serve the nation”.

Rumors of Rahul Gandhi joining the cabinet in the next reshuffle have been doing the rounds lately. But as and when that happens Rahul Gandhi will have to let go of what seems like an unwillingness to be open.

People will analyse what he says. He may still not give interviews but as a minister he will surely have to make speeches, address meetings etc. His decisions will be closely watched. And the files he signs on will be open to RTI filings. In short, the mystery surrounding him will come down.

Things as they are currently will have to change. As Ramachandran puts it “In situations where he is required to speak, whether it is the Parliament or his elections speeches, he is uncomfortable. He is only now beginning to find his public speaking voice. For the most part, however, he has tended to avoid speaking in the public or to the press on issues. He comes across as a politician who is reluctant to share his views on issues of national importance or worse as someone who does not have views at all.”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on Ocotber 19,2012.

http://www.firstpost.com/india/rahul-reluctant-politician-who-was-once-afraid-of-the-dark-495947.html

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

The Singh Talkies

Vivek Kaul

One of my favourite Hollywood comedies is Mel Brooks’ Silent Movie made in 1976. As its name suggests, the film had no dialogue and the only audible word in the movie is spoken by Marcel Marceau, when he utters the word “No!” Rather ironically Marceau was one of the most famous mime artists of the era.

The Congress party led UPA in the last few years has been behaving in the opposite way.In the Congress movie every leader other than Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, the man at the top, had a dialogue. Singh chose to keep quiet rarely telling us what was going on inside his head, as his government moved from one scam to another.

But over the last two weeks he has suddenly found his voice, initiated a wave of reforms, from increasing the price of diesel by Rs 5 per litre to allowing foreign direct investment in the retail sector. “It will take courage and some risks but it should be our endeavour to ensure that it succeeds. The country deserves no less,” Singh said after the announcements were made.

He even addressed the nation and explained the rationale behind the decisions. The media went to town saying that Manmohan has got his mojo back. But the question is what has got our silent Prime Minister talking?

When Pranab Mukherjee presented the budget earlier this year he had projected a fiscal deficit of Rs 5,13,590 crore or 5.1% of the gross domestic product(GDP). Fiscal deficit is the difference between what the government earns and what it spends.

The projected fiscal deficit has gone all awry primarily because the price of oil has continued to remain high, despite a slowdown in the global economy. Currently, the price of the Indian basket of crude oil is at around $114.4 per barrel.

This wouldn’t have been a problem if the diesel, kerosene and cooking gas, would have been sold at their market price. But the Indian government hasn’t allowed that to happen over the years and has protected the consumers against the price rise. This means that the oil marketing companies (OMCs) Indian Oil, Bharat Petroleum and Hindustan Petroleum have had to sell diesel, kerosene and cooking gas at a loss.

The government needs to compensate these companies from the losses they incur, so that they don’t go bankrupt. These losses were close to touching Rs 1,90,000 crore, when the government decided to increase the price of diesel by Rs 5 per litre. Even after this increase the OMCs will lose over Rs 1,00,000 crore just on the sale of diesel this year. The total loss on diesel, kerosene and cooking gas is now estimated to be at Rs 1,67,000 crore. The OMCs are also losing around Rs 6 per litre on selling petrol, but the government doesn’t compensate them for this.

The government hadn’t budgeted for such huge losses on the oil front in the budget. The budgeted amount was a miniscule Rs 43,580 crore. Of this nearly Rs 38,500 crore was used to compensate the OMCs for losses made during the course of the lost financial year, leaving a little over Rs 5,000 crore to meet the losses for the current financial year.

The subsidies allocated for food and fertiliser are also likely to be not enough. In fact as per the Controller General of Accounts the fiscal deficit during the first four months of the year has already crossed half of the budgeted fiscal deficit of Rs 5,13,590 crore. This was a really worrying situation. More than that with tensions flaring up again in various countries in the Middle East, it is unlikely that the price of oil will come down in a hurry.

Given these reasons if the government had carried on in its current state there was a danger of the fiscal deficit crossing Rs 7,00,000 crore or 7% of the GDP. This is a situation which India has never had to face since the country first initiated and embraced economic reforms in July 1991. The fiscal deficit for the year 1990-1991 had stood at 8% of the GDP.

Reforms like allowing foreign investment in multi brand retailing will have an impact on economic growth over a very long period of time, if at all they do. Allowing foreign investors to pick up 49% stake in domestic airlines will also not have any immediate impact. But what is more important is the signals that these reforms send out to the market i.e. policy logjam that was holding economic growth back is over and the government is now in the mood for reforms.

As a result the rupee has appreciated against the dollar. One dollar was worth Rs 55.4 on September 14. Since then it has gained 3% to Rs 53.8. This will help in bringing the oil bill down. Oil is sold internationally in dollars. When one barrel costs $115 and one dollar is worth Rs 55.4, India pays Rs 6,371 per barrel. If one dollar is worth Rs 53.8, then India pays a lower Rs 6,187 per barrel. So an appreciating rupee brings down the oil bill, which in turn pushes down the fiscal deficit of the government.

The thirty share BSE Sensex has rallied by 2.9% to 18,542.3 points, from its close on September 13 to September 17. Nevertheless, even after these moves the actual fiscal deficit of the government will be substantially higher than the targeted Rs 5,13,590 crore. To bring that down the government needs to come up with more reforms so that the rupee continues to appreciate against the dollar and brings down the oil subsidy bill. The market rally also needs to continue, so that the government meets its disinvestment target of Rs 30,000 crore for the year. And on top of all this the government also needs to reign in the oil subsidy by gradually increasing prices of petrol, diesel, kerosene and cooking gas. Unless this happens, the government will continue to borrow more and this will keep interest rates high. Interest rates need to come down if businesses and consumers are to start borrowing again. This is necessary to revive economic growth, which has slowed down considerably.

If all this wasn’t enough we also need to hope that a certain Mrs G and Master G need to continue to understand that good economics also means good politics. If they switch off anytime now, Manmohan Singh is likely to go quiet again.

(A slightly different version of the article with a different headline appeared in the Asian Age/Deccan Chronicle on September 26, 2012. http://www.deccanchronicle.com/editorial/dc-comment/good-economics-good-politics-too-426)

(Vivek Kaul is a Mumbai based writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

One Bofors got Rajiv. But will UPA’s bag of scams hurt Cong?

Vivek Kaul

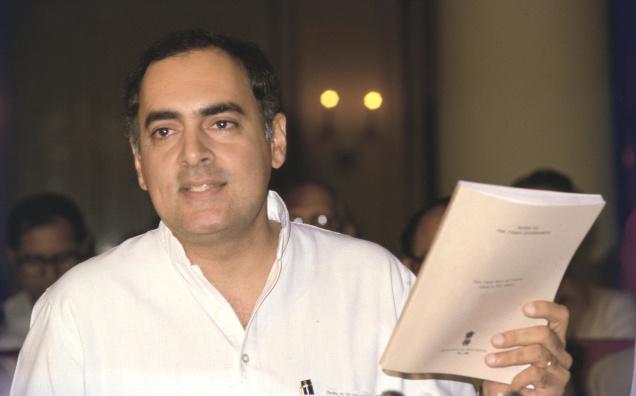

It was May 22, 1991. My summer holidays were on. And I was at my grandfather’s duplex flat in South Delhi. I had woken up very late. It must have been around 10.30am. As soon as I came down to the lower level, an uncle who has since become an Art of Living guru, told me that Rajiv Gandhi had been killed late last night( he didn’t use the word assassinated, that I remember very clearly).

Given his penchant for practical jokes, I thought that he was pulling a fast one on me, early in the morning. Those were the days before cable television became a part of our everyday lives, and so I picked up the Hindustan Times newspaper, my grandfather used to subscribe to, in order to verify whether he was really speaking the truth.

And as it turned out my uncle wasn’t lying. He wasn’t playing a practical joke. Rajiv Gandhi had been assassinated by a human bomb at 10.10pm on May 21. “Bofors killed him,” was a random remark I heard during the course of that day. But since summer holidays were on I had better things to think about than Bofors and how it killed Rajiv Gandhi.

This entire incident came back to me while reading an excerpt of an upcoming book titled Decoding Rahul Gandhi written by Aarthi Ramachandran. As she writes “Sonia writes in Rajiv that Rahul would telephone from America, “consumed with anxiety” about his father’s security arrangements. She says Rajiv’s specialised security cover was withdrawn after he became leader of the opposition and it was replaced with a force not trained for this specific task. Rahul, who had gone to the US in June 1990 to start his undergraduate studies at Harvard University, insisted on coming back to India at the end of March 1991 for his Easter break. He accompanied his father on a tour of Bihar and was “appalled to witness the lack of elementary security around his father”. Sonia says that before going back to the US, Rahul had told her that if something was not done about it, he knew he would soon come home for his father’s funeral.”

Something did happen to Rajiv Gandhi a couple of months later and Rahul had to comeback from Harvard for the funeral.

Rajiv Gandhi had taken over as the Prime Minister of India after the assassination of his mother Indira by her bodyguards. Riding on his honest image and sympathy for his mother the Congress party got around half the votes polled and more than 400 seats of the total 515 seats in the Lok Sabha.

In 1987, the Bofors scandal came into light and tarred the honest image of Rajiv Gandhi. Bofors AB, a Swedish company, had supposedly paid kickbacks to top Indian politicians of around Rs64 crore to swing around a $285million contracts for Howitzer field guns in its favour.

The impact of this on the Congress party was huge. It lost the 1989 election to an alliance of Janta Dal and Bhartiya Janta Party. Rajiv Gandhi had to become the leader of opposition. His security was downgraded and he was assassinated two years later. So in a way Bofors killed Rajiv Gandhi.

But if one takes into account the size of the scam at Rs 64 crore it was hardly anything in size to the scams that have come into light over the last few years. The coal scam. The telecom scam. The commonwealth games scam. The Adarsh Housing Society scam. The Devas Antrix scam. And so on.

Each one of these scams has been monstrous in proportion to the Rs 64 crore Bofors scam. There has been a surfeit of scams coming to light since in the second tenure of the Congress led United Progressive Alliance started. These scams would have been on for a while but they have been coming to light only over the last couple of years.

The Canadian American Economist John Kenneth Galbraith has an explanation for this phenomenon in his book The Great Crash 1929. “At any given time there exists an inventory of undisclosed embezzlement. This inventory – it should perhaps be called the bezzle – amounts at any moment to many millions of dollars. In good times people are relaxed ,trusting, and money is plentiful. … Under these circumstances the rate of embezzlement grows, the rate of discovery falls o , and the bezzle increases rapidly. In depression all this is reversed. … Just as the (stock market boom) accelerated the rate of growth (of embezzlement), so the crash enormously advanced the rate of discovery.”

In an Indian context the economy and the stock market were booming between 2004 and 2008. 2009 was a bad year. Things recovered a bit in 2010. And have been looking bleak since the middle of 2011. And it is since then when all these scams have been coming to light. Galbraith’s explanation clearly works here. When things were good the scams were being created and as things turned around, all the scams have been coming to light.

But the bigger question here is will the people of this country remember about all these scams (and more that may be highlighted in the days to come) by the time the 2014 Lok Sabha elections come around? One Bofors scandal running into a few million dollars was enough to put Rajiv Gandhi out of power and even take his life in the end. But will all these billion dollar scandals carry enough weight in the days to come? Or will they just become background noise, leading to people not bothering about them, while deciding who to vote for in 2014?

As Umberto Eco (an Italian author) and Jean Claude Carriere (a french scriptwriter) write in This is Not the End of the Book: “But an abundance of witnesses isn’t necessarily enough. We witnessed the violence inflicted on Tibetan monks by the Chinese police. It provoked international outrage. But if your screens kept showing monks being beaten by police for months on end, even the most concerned and active audience would lose interest. There is therefore a level below which, news pieces do not penetrate and above which they become nothing but background noise.”

Isn’t India going through the same situation right now when it comes to scams? There is a race on among various sections of the media to highlight more and more scams (and rightly so). News channels talk about scams all day long. The front pages of newspapers are full of it. And so is the social media. So will a surfeit of scams make us immune to them?

I don’t have hard and fast answers to the questions that I have raised here. But I do have this lurking feeling that all this scam talk everywhere might just end up benefitting the Congress led UPA government, rather than hurting it. Or to put it in a better way it might not hurt the Congress led UPA as much as it should.

(The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on September 4,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/india/one-bofors-got-rajiv-but-will-upas-bag-of-scams-hurt-cong-443064.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Reform by stealth, the original sin of 1991, has come back to haunt us

India badly needs a second generation of economic reforms in the days and months to come. But that doesn’t seem to be happening. “What makes reforms more difficult now is what I call the original sin of 1991. What happened from 1991 and thereon was reform by stealth. There was never an attempt made to sort of articulate to the Indian voter why are we doing this? What is the sort of the intellectual or the real rationale for this? Why is it that we must open up?” says Vivek Dehejia an economics professor at Carleton University in Ottawa,Canada. He is also a regular economic commentator on India for the New York Times India Ink. In this interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul.

How do you see overall Indian economy right now?

The way I would put it Vivek is, if I take a long term view, a generational view, I am pretty optimistic. The fundamentals of savings and investments are strong.

What about a more short term view?

If you take a shorter view of between six months to a year or even two years ahead, then everything that we have been reading about in the news is worrisome. The foreign direct investment is drying up. The savings rate seems to have been dropping. The economic growth we know has dropped. The next fiscal year we would lucky if we get 6.5% economic growth.

How do we account for the failure of this particular government to deliver sort of crucially needed second generation economic reforms?

The India story is a glass half empty or a glass half full. If you look at the media’s treatment of the India story, particularly international media they tend to overshoot. So two years ago we were being overhyped. I remember that the Economist had a famous cover where they said that India will overtake China’s growth rate in the next couple of years. They made that bold prediction. And then about a year later they were saying that India is a disaster. What has happened to the India story? The international media tends to overshoot. And then they overdo it in the negative direction as well. A balanced view would say that original hype was excessive. We cannot do nor would we want to do what China is doing. With our democratic system, our pluralistic democracy, the India that we have, we cannot marshal resources like the way the Chinese do, or like the way Singapore did.

Could you discuss that in detail?

If you take a step back, historically, many of the East Asian growth miracles, the Latin American growth miracles, were done under brutal dictatorial regimes. I mean whether it was Pinochet’s Chile, whether it was Taiwan or Singapore or Hong Kong, they all did it under authoritarian regimes. So the India story is unique. We are the only large emerging economy to have emerged as a fully fledged democracy the moment we were born as a post colonial state and that is an incredibly daring thing to do. At the time when the Constituent Assembly was figuring out what are we going to do now post independence a lot of conservative voices were saying don’t go in for full fledged democracy where every person man or a woman gets a vote because you will descend down into pluralism and identity based politics and so on. Of course to some extent it’s true. A country with a large number of poor people which is a fully fledged democracy, the centre of gravity politically is going to be towards redistribution and not towards growth. So any government has to reckon with the fact that where are your votes. In other words the market for votes and the market for economic reform do not always correlate.

You talk about authoritarian regimes and growth going together…

This is one of the oldest debates in social sciences. It is a very unsettled and a very controversial one. For any theory you can give on one side of it there is an equally compelling argument on the other side. So the orthodox view in political science particularly more than economics was put forward by Samuel Huntington. The view was that you need to have some sort of political control, you cannot have a free for all, and get marshalling of resources and savings rate and investment rate, that high growth demands.

So Huntington was supportive of the Chinese model of growth?

Yes. Huntington famously was supportive of the Chinese model and suggested that was what you had to do at an early stage of economic development. But there are equally compelling arguments on the other side as well. The idea is that democracy gives a safety valve for a discontent or unhappiness or for popular expression to disapproval of whatever the government or the regime in power is doing. We read about the growing number of mysterious incidents in China where you can infer that people are rioting. But we are not exactly sure because the Chinese system also does not allow for a free media. Also let’s not forget that China has had growing inequalities of income and growth, and massive corruption scandals. The point being that China too for its much wanted economic efficiency also has kinds of problems which are not much different from the once we face.

That’s an interesting point you make…

Here again another theory or another idea which can help us interpret what is going on. When you have a period of rapid economic growth and structural transformation of an economy, you are almost invariably going to have massive corruption. It is almost impossible to imagine that you have this huge amount of growth taking place in a relatively weak regulatory environment where there isn’t going to be an opportunity for corruption. It doesn’t mean that it is okay or it doesn’t mean that one condones it, but if you look throughout history it’s always been the case that in the first phase of rapid growth and rapid transformation there has been corruption, rising inequalities and so on.

Can you give us an example?

The famous example is the so called American gilded age. In the United States after the end of the Civil War (in the 1860s) came the era of the Robber Barons. These people who are now household names the Vanderbilts, the Rockefellers, the Carnegies, the Mellons, were basically Robber Barons. They were called that of course because how they operated was pretty shady even according to the rules of that time.

Why are the second generation of reforms not happening?

What makes reforms more difficult now is what I call the original sin of 1991. We had a first phase of the economic reforms in 1991 where we swept away the worst excesses of the license permit raj. We opened up the product markets. But what happened from 1991 and thereon was reform by stealth. Reform by the stroke of the pen reform and reform in a mode of crisis, where there was never an attempt made to sort of articulate to the Indian voter why are we doing this? What is the sort of the intellectual or the real rationale for this? Why is it that we must open up? It wasn’t good enough to say that look we are in a crisis. Our gold reserves have been mortgaged. Our foreign exchange reserves are dwindling. Again India’s is hardly unique on this. Wherever you look whether it is Latin America or Eastern Europe, it generally takes an economic crisis to usher in a period of major economic reform.

So the original sin is still haunting us?

The original sin has come back to haunt us because the intellectual basis of further reform is not even on anyone’s agenda. Discussions and debates on reform are more focused on issues like the FDI is falling, the rupee is falling, the current account deficit is going up etc. Those are all symptoms of a problem. The two bursts of reform that we had first were first under Rao/Manmohan Singh and then under NDA. If a case had been made to build a constituency for economic reform, then I think we would have been in a different political economy than we are now. But the fact that didn’t happen and things were going well, the economy was growing, that led to a situation where everybody said let’s carry on. But now we don’t have that luxury. Now whichever government whoever comes to power in 2014 is going to have to make some tough decisions that their electoral base, isn’t going to like necessarily. So how are they going to make their case?

So are you suggesting that the next generation of reforms in India will happen only if there is an economic crisis?

I don’t want to say that. Again that could be one interpretation from the arguments I am making of the history. It will require a change in the political equilibrium and certainly a crisis is one thing that can do that. But a more benign way the same thing can happen that without a crisis is the realization of the political actors that look I can make economic reform and economic growth electorally a winning policy for me. But India is a land of so many paradoxes. A norm of the democratic political theory in the rich countries i.e. the US, Canada, Great Britain etc, is that other things being equal, the richer you are, the more educated you are, the more likely you are to vote. In India it is the opposite. The urban middle class is the more disengaged politically. They feel cynical. They feel powerless. Until they become more politically engaged that change in the equilibrium cannot happen.

What about the rural voter?

The rural voter at least in the short run might benefit from a NREGA and will say that you are giving me money and I will keep voting for you. We have all heard people say they are uneducated and they are ignorant, no it’s not like that. He is in a very liquidity constrained situation. He is looking to the next crop, the next harvest, the next I got to pay my bills. If someone gave him 100 days of employment and gives him a subsidy, he will take it.

How do explain the dichotomy between Manmohan Singh’s so called reformist credentials and his failure to carry out economic reforms?

One of the misconceptions that crops up when we look at poor economic performance or failure to carry out economic reform is what cognitive psychologists call fundamental attribution bias. Fundamentally attribution bias says that we are more likely to attribute to the other person a subjective basis for their behaviour and tend to neglect the situational factors. Looking at our own actions we look more at the situational factors and less at the idiosyncratic individual subjective factors. So what am I trying to say? What I am saying is that it has become almost a refrain to say that Dr Manmohan Singh should be an economic reformer. He was at least the instrument if not the architect of the 1991 reforms. There are speculations being in made in what you can call the Delhi and Mumbai cocktail party circuit, about whether he is really a reformer? Was it Narsimha Rao who was really the real architect of the reform? Is he a frustrated reformer? What does he really want to do? What’s going on his head? That in my view is a fundamental attribution bias because we are attributing to him or whoever is around him a subjective basis for the inaction and the policy paralysis of the government.

So the government more than the individual at the helm of it is to be blamed?

Traditionally the electoral base of the Congress party has been the rural voter, the minority voters and so on, people who are at the lower end of the economic spectrum. So they are the beneficiaries just roughly speaking of the redistributive policies. Political scientists have a fancy name for it. They call it the median voter theorem. What does it mean? It means that all political parties will tend to gravitate towards the preferred policy of the guy in the middle, the median voter.

Was Narsimha Rao who was really the real architect of the reform?

Narsimha Rao must be given a lot of credit for taking what was then a very bold decision. He was at the top of a very weak government as you know. And he gave the political backing to Manmohan Singh to push this first wave of reforms more than that would have been necessary just to avert a foreign exchange crisis. And then he paid a price for it electorally in the next election. This again the intangible element in the political economy that short of a crisis it often takes someone of stature to really take that long term generation view. IT means that you are not just looking at narrow electoral calculus but you are looking beyond the next election. That’s what seems to be missing right now. Among all the political parties right now, one doesn’t seem to see that vision of look at this is where we want to be in a generation and here is our roadmap of how we are going to get there.

Going back to Manmohan Singh you called him an overachiever recently, after the Time magazine called him an “underachiever”. What was the logic there?

The traditional view and certainly that was widely in the West at least till very recently has been that it was Manmohan Singh who was the architect of the India’s economic reforms. But then how do you explain the inaction in the last five, six, seven years? The revisionist perspective would say no in fact the real reformer was Narsimha Rao to begin with. The real political weight behind the reform was his. And Manmohan Singh that any good technocratic economist should have been able to do which is to implement a series of reforms that we all knew about. My teacher Jagdish Bhagwati had been writing about it for years. In that sense maybe Manmohan Singh was given too much credit in the first instance for implementing a set of reforms. If you look at his career since then he has never really been a politically savvy actor. We have this peculiar situation in India since 2004 where the Prime Minister sits in the Rajya Sabha, the upper house. That kind of thing is not barred by our constitution but I don’t think that the framers of the constitution envisaged this would be a long term situation. It is a little like the British prime minister sitting in the House of Lords. I mean that practice disappeared in the nineteenth century. He has not shown from the evidence that we can see any ability to get a political base of his own to be a counterweight to the more redistributive tendencies of the Nehru Gandhi dynasty. And that’s the sense that in somewhat cheeky way I was using the term overachiever.

Do you think he is just keeping the seat warm for Rahul Gandhi?

It increasingly appears to be that way. If that is true then it suggests that we shouldn’t really expect much to happen in the next two years.

Does the fiscal deficit of India worry you?

If you look at some shorter to medium term challenges, then things like fiscal deficit and the current account deficit are things to worry about. Again other things like the weak rupee, the weak FDI data, things that people tend to fixate at, but those at best are symptoms of a deeper structural problem. The deeper concern is the kind of reform that will require a major legislative agenda such as labour law reform for example to unlock our manufacturing sector. And managing the huge demographic dividend that we are going to get in the form of 300-400 million young people. They will have to be educated.

But is there a demographic dividend?

That’s the question. Will it become a demographic nightmare? Can you imagine the social chaos if you have all these kids just wandering around, not educated enough to get a job, what are they going to do? It’s a recipe for social disaster. That according to me is going to be real litmus test. If we are able to navigate that then I don’t see why we won’t be on track to again go back to 8- 9% economic growth. I want to remain optimistic at the end of the day.

(The interview originally appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on August 6,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/money/interview_reform-by-stealth-the-originalsin-of-1991-has-come-back-to-haunt-us_1724348)

(Interviewer Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])