Vivek Kaul

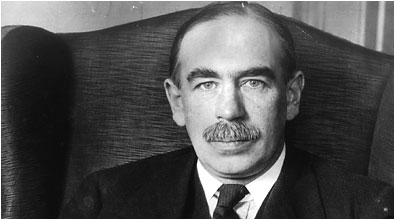

John Maynard Keynes (pictured above) was a rare economist whose books sold well even among the common public. The only exception to this was his magnum opus, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, which was published towards the end of 1936.

In this book Keynes discussed the paradox of thrift or saving. What Keynes said was that when it comes to thrift or saving, the economics of the individual differed from the economics of the system as a whole. An individual saving more by cutting down on expenditure made tremendous sense. But when a society as a whole starts to save more then there is a problem. This is primarily because what is expenditure for one person is income for someone else. Hence when expenditures start to go down, incomes start to go down, which leads to a further reduction in expenditure and so the cycle continues. In this way the aggregate demand of a society as a whole falls which slows down economic growth.

This Keynes felt went a long way in explaining the real cause behind The Great Depression which started sometime in 1929. After the stock market crash in late October 1929, people’s perception of the future changed and this led them to cutting down on their expenditure, which slowed down different economies all over the world.

As per Keynes, the way out of this situation was for someone to spend more. The best way out was the government spending more money, and becoming the “spender of the last resort”. Also it did not matter if the government ended up running a fiscal deficit doing so. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what the government earns and what it spends.

What Keynes said in the General Theory was largely ignored initially. Gradually what Keynes had suggested started playing out on its own in different parts of the world.

Adolf Hitler had put 100,000 construction workers for the construction of Autobahn, a nationally coordinated motorway system in Germany, which was supposed to have no speed limits. Hitler first came to power in 1934. By 1936, the Germany economy was chugging along nicely having recovered from the devastating slump and unemployment. Italy and Japan had also worked along similar lines.

Very soon Britain would end up doing what Keynes had been recommending. The rise of Hitler led to a situation where Britain had to build massive defence capabilities in a very short period of time. The Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was in no position to raise taxes to finance the defence expenditure. What he did was instead borrow money from the public and by the time the Second World War started in 1939, the British fiscal deficit was already projected to be around £1billion or around 25% of the national income. The deficit spending which started to happen even before the Second World War started led to the British economy booming.

This evidence left very little doubt in the minds of politicians, budding economists and people around the world that the economy worked like Keynes said it did. Keynesianism became the economic philosophy of the world.

Lest we come to the conclusion that Keynes was an advocate of government’s running fiscal deficits all the time, it needs to be clarified that his stated position was far from that. What Keynes believed in was that on an average the government budget should be balanced. This meant that during years of prosperity the governments should run budget surpluses. But when the environment was recessionary and things were not looking good, governments should spend more than what they earn and even run a fiscal deficit.

The politicians over the decades just took one part of Keynes’ argument and ran with it. The belief in running deficits in bad times became permanently etched in their minds. In the meanwhile they forgot that Keynes had also wanted them to run surpluses during good times. So they ran deficits even in good times. The expenditure of the government was always more than its income.

Thus, governments all over the world have run fiscal deficits over the years. This has been largely financed by borrowing money. With all this borrowing governments, at least in the developed world, have ended up with huge debts to repay. What has added to the trouble is the financial crisis which started in late 2008. In the aftermath of the crisis, governments have gone back to Keynes and increased their expenditure considerably in the hope of reviving their moribund economies.

In fact the increase in expenditure has been so huge that its not been possible to meet all of it through borrowing money. So several governments have got their respective central banks to buy the bonds they issue in order to finance their fiscal deficit. Central banks buy these bonds by simply printing money.

All this money printing has led to the Federal Reserve of United States expanding its balance sheet by 220% since early 2008. The Bank of England has done even better at 350%. The European Central Bank(ECB) has expanded its balance sheet by around 98%. The ECB is the central bank of the seventeen countries which use the euro as their currency. Countries using the euro as their currency are in total referred to as the euro zone.

The ECB and the euro zone have been rather subdued in their money printing operations. In fact, when one of the member countries Cyprus was given a bailout of € 10 billion (or around $13billion), a couple of days back, it was asked to partly finance the deal by seizing deposits of over €100,000 in its second largest bank, the Laiki Bank. This move is expected to generate €4.2 billion. The remaining money is expected to come from privatisation and tax increases, over a period of time.

It would have been simpler to just print and handover the money to Cyprus, rather than seizing deposits and creating insecurities in the minds of depositors all over the Euro Zone.

Spain, another member of the Euro Zone, seems to be working along similar lines. Loans given to real estate developers and construction companies by Spanish banks amount to nearly $700 billion, or nearly 50 percent of the Spain’s current GDP of nearly $1.4 trillion. With homes lying unsold developers are in no position to repay. And hence Spanish banks are in big trouble.

The government is not bailing out the Spanish banks totally by handing them freshly printed money or by pumping in borrowed money, as has been the case globally, over the last few years. It has asked the shareholders and bondholders of the five nationalised banks in the country, to share the cost of restructuring.

The modus operandi being resorted to in Cyprus and Spain can be termed as an extreme form of financial repression. Russell Napier, a consultant with CLSA, defines this term as “There is a thing called financial repression which is effectively forcing people to lend money to the…government.” In case of Cyprus and Spain the government has simply decided to seize the money from the depositors/shareholders/bondholders in order to fund itself. If the government had not done so, it would have had to borrow more money and increase its already burgeoning level of debt.

In effect the citizens of these countries are bailing out the governments. In case of Cyprus this may not be totally true, given that it is widely held that a significant portion of deposit holders with more than €100,000 in the Cyprian bank accounts are held by Russians laundering their black money.

But the broader point is that governments in the Euro Zone are coming around to the idea of financial repression where citizens of these countries will effectively bailout their troubled governments and banks.

Financing expenditure by money printing which has been the trend in other parts of the world hasn’t caught on as much in continental Europe. There are historical reasons for the same which go back to Germany and the way it was in the aftermath of the First World War.

The government was printing huge amounts of money to meet its expenditure. And this in turn led to very high inflation or hyperinflation as it is called, as this new money chased the same amount of goods and services. A kilo of butter cost ended up costing 250 billion marks and a kilo of bacon 180 billion marks. Interest rates as high as 22% per day were deemed to be legally fair.

Inflation in Germany at its peak touched a 1000 million %. This led to people losing faith in the politicians of the day, which in turn led to the rise of Adolf Hitler, the Second World War and the division of Germany.

Due to this historical reason, Germany has never come around to the idea of printing money to finance expenditure. And this to some extent has kept the total Euro Zone in control(given that Germany is the biggest economy in the zone) when it comes to printing money at the same rate as other governments in the world are. It has also led to the current policy of financial repression where the savings of the citizens of the country are forcefully being used to finance its government and rescue its banks.

The question is will the United States get around to the idea of financial repression and force its citizens to finance the government by either forcing them to buy bonds issued by the government or by simply seizing their savings, as is happening in Europe.

Currently the United States seems happy printing money to meet its expenditure. The trouble with printing too much money is that one day it does lead to inflation as more and more money chases the same number of goods, leading to higher prices. But that inflation is still to be seen.

As Nicholas NassimTaleb puts it in Anti Fragile “central banks can print money; they print print and print with no effect (and claim the “safety” of such a measure), then, “unexpectedly,” the printing causes a jump in inflation.”

It is when this inflation appears that the United States is likely to resort to financial repression and force its citizens to fund the government. As Russell Napier of CLSA told this writer in an interview “I am sure that if the Federal Reserve sees inflation climbing to anywhere near 10% it would go to the government and say that we cannot continue to print money to buy these treasuries and we need to force financial institutions and people to buy these treasuries.” Treasuries are the bonds that the American government sells to finance its fiscal deficit.

“May you live in interesting times,” goes the old Chinese curse. These surely are interesting times.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on March 27,2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Money printing

What the humble electric toaster tells us about the global financial system

Vivek Kaul

Tim Harford writer of such excellent books like The Undercover Economist, The Logic of Life and Adapt, once wrote a blog discussing the perils of a design student trying to make an electric toaster from scratch.

Harford discusses the experience of Thomsan Thwaites, a postgraduate design student, who decided to embark on what he called “The Toaster Project”. “Quite simply, Thwaites wanted to build a toaster from scratch,” writes Harford.

The toaster was first invented in 1893 and is a household good in Great Britain and almost all other parts of the developed world. It costs a few pounds and is very reliable and efficient. But building it from scratch was still not a joke. “To obtain the iron ore, Thwaites had to travel to a former mine in Wales that now serves as a museum. His first attempt to smelt the iron using 15th-century technology failed dismally. His second attempt was something of a cheat, using a recently patented smelting method and a microwave oven – the microwave oven was a casualty of the process – to produce a coin-size lump of iron,” writes Harford.

Next Thwaites needed plastic. Plastic is made from oil. But Thwaites never made it to an oil rig. He finally settled at scavenging plastic from a local dump, which he melted and then moulded into a toaster casing.

More short cuts followed. As Harford writes “Copper he obtained via electrolysis from the polluted water of an old mine… Nickel was even harder; he cheated and bought some commemorative coins, melting them with an oxyacetylene torch. These compromises were inevitable.”

A simple toaster has nearly 400 components and sub components which is made from nearly 100 different materials. So imagine the difficulty if everything had to be procured and made from scratch. As Thwaites told Harford “I realised that if you started absolutely from scratch, you could easily spend your life making a toaster.”

Thwaites finally did manage to make an electric toaster, but it was nowhere as good as the ones easily available in the market. As Harford writes “Thwaites’s home-made toaster is a simpler affair, using just iron, copper, plastic, nickel and mica, a ceramic. It looks more like a toaster-shaped birthday cake than a real toaster, its coating dripping and oozing like icing gone wrong. “It warms bread when I plug it into a battery,” he says, brightly. “But I’m not sure what will happen if I plug it into the mains.””

So dear reader, you might be reading this piece sitting in the air-conditioned comforts of your office on an ergonomically designed chair (hopefully). Or you might be sitting at home reading this on your laptop. Or you must be travelling in a bus/metro/local train hanging onto your life and reading this on your android smartphone. Or you must be waiting for your aircraft to take off and must be quickly glancing through this on your iPad.

The question that crops up here is that how many of the things mentioned in the last paragraph, would you dear reader, be able to make on your own? The answer is none. So then where did all these things that make life so comfortable come from?

Dylan Grice answers this question in the latest issue (dated March 11, 2013) of the Edelweiss Journal. “So where did it all come from? Strangers, basically. You don’t know them and they don’t know you. In fact virtually none of us know each other. Nevertheless, strangers somehow pooled their skills, their experience and their expertise so as to conceive, design, manufacture and distribute whatever you are looking at right now so that it could be right there right now.”

Estimates suggest that cities like London and New York offer ten billion distinct kinds of products. So what makes this possible? “Exchange. To be able to consume the skills of these strangers, you must sell yours,” writes Grice. It is impossible for a single human being to even make something as simple as a toaster from scratch. But when many people specialise in their respective areas and develop certain skills, only then does a product as simple as a toaster become possible.

Let me take my example. I sell my writing skills. With the compensation that I get I buy goods and services that I need for my existence. From something as basic as food, water and electricity, which I need to survive or comforts like buying a washing machine to wash clothes, a refrigerator so that I don’t need to cook on a day to day basis, hiring a taxi to travel in or catching the latest movie at the local multiplex.

At the heart of any exchange is trust. As Grice puts it “we must also understand that exchange is only possible to the extent that people trust each other: when eating in a restaurant we trust the chef not to put things in our food; when hiring a builder we trust him to build a wall which won’t fall down; when we book a flight we entrust our lives and the lives of our families to complete strangers.”

So for any exchange to happen, there needs to be trust. But trust is not the only thing that facilitates exchange. There is another important ingredient. And that is money.

Money has been thoroughly abused all over the world in the aftermath of the financial crisis which broke out officially in September 2008. Central banks egged on by governments all over the world have printed money, in an effort to revive their respective economies. The idea being that with more money in the financial system, banks will lend more which will lead to people spending more and that will help revive the economy.

But all this comes with a cost. “So when central banks play the games with money of which they are so fond, we wonder if they realize that they are also playing games with social bonding. Do they realize that by devaluing money they are devaluing society?” asks Grice.

Allow me to explain. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, government expenditure all over the world has shot up dramatically. This expenditure could have been met by raising taxes. But when economies are slowing down this isn’t the most prudent thing to do. The next option was to borrow money. But there was only so much money that could be borrowed. So the governments utilised the third possible option. They got their central banks to print money. Central banks used this printed money to buy government bonds. Thus the governments could meet their increased expenditure.

When a government increases tax to meet its expenditure, everyone knows who is paying for it. It’s the taxpayer. But the answer is not so simple when the government meets its expenditure by printing money. As Grice puts it “When the government raises revenue by selling bonds to the central bank, which has financed its purchases with printed money, no one knows who ultimately pays.”

But then that doesn’t mean that nobody pays.

With the central bank printing money, the money supply in the financial system goes up. And this benefits those who are closest to the “new” money. Richard Cantillon, a contemporary of Adam Smith, explained this in the context of gold and silver coming into Spain from what was then called the New World (now South America).

As he wrote: “If the increase of actual money comes from mines of gold or silver… the owner of these mines, the adventurers, the smelters, refiners, and all the other workers will increase their expenditures in proportion to their gains.” These individuals would end up with a greater amount of gold and silver, which was used as money, back then. This money they would spend and thus drive up the prices of meat, wine, wool, wheat etc. This rise in prices would impact even people not associated with the mining industry even though they wouldn’t have seen a rise in their incomes like the people associated with the mining industry had.

So is this applicable in the present day context? The money printing that has happened in recent years has benefited those who are closest to the money creation. This basically means the financial sector and anyone who has access to cheap credit. Institutional investors have been able to raise money at close to zero percent interest rates and invest them in all kinds of assets all over the world. As Ruchir Sharma writes in Breakout Nations – In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles:

“What is apparent that central banks can print all the money they want, they can’t dictate where it goes. This time around, much of that money has flown into speculative oil futures, luxury real estate in major financial capitals, and other non productive investments…The hype has created a new industry that turns commodities into financial products that can be traded like stocks. Oil, wheat, and platinum used to be sold primarily as raw materials, and now they are sold largely as speculative investments.”

While financial investors benefit, the common man ends up paying more for the goods and services that he buys, something that is not always captured in the inflation number. As Grice puts it: “So now we know we have a slightly better understanding of who pays: whoever is furthest away from the newly created money. And we have a better understanding of how they pay: through a reduction in their own spending power. The problem is that while they will be acutely aware of the reduction in their own spending power, they will be less aware of why their spending power has declined. So if they find groceries becoming more expensive they blame the retailers for raising prices; if they find petrol unaffordable, they blame the oil companies; if they find rents too expensive they blame landlords, and so on. So now we see the mechanism by which debasing money debases trust. The unaware victims of this accidental redistribution don’t know who the enemy is, so they create an enemy.”

And people all over the world are doing a thoroughly good job of creating “enemies”. “The 99% blame the 1%; the 1% blame the 47%. In the aftermath of the Eurozone’s own credit bubbles, the Germans blame the Greeks. The Greeks round on the foreigners. The Catalans blame the Castilians. And as 25% of the Italian electorate vote for a professional comedian whose party slogan “vaffa” means roughly “f**k off ” (to everything it seems, including the common currency), the Germans are repatriating their gold from New York and Paris. Meanwhile in China, that centrally planned mother of all credit inflations, popular anger is being directed at Japan.”

This is only going to increase in the days and years to come. As Grice writes in a report titled Memo to Central Banks: You’re debasing more than our currency (October 12, 2012) “History is replete with Great Disorders in which social cohesion has been undermined by currency debasements…Yet central banks continue down the same route. The writing is on the wall. Further debasement of money will cause further debasement of society. I fear a Great Disorder.”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on March 21, 2013

Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek

I fear a Great Disorder

Dylan Grice is a strategist with Societe Generale and is based out of London. He is the co-author of the French investment bank’s much-followed Popular Delusions analysis. “History is replete with Great Disorders in which social cohesion has been undermined by currency debasements. The multi-decade credit inflation can now be seen to have had similarly corrosive effects… I fear a Great Disorder,” he says. In this interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul.

What is debasement of currency?

Sometimes the most basic questions are the biggest ones! I’ll try to keep it as simple as possible by defining currency debasement as an increase in the supply of money which increases the purchasing power of whomever issues that money, by reducing purchasing power for everyone else.

And since when is it happening?

In the story of our civilisation, coins of a defined weight first appear at around at around 700BC. Around 400BC Aristophanes references inflation in his comedyThe Frogs, probably a reference to the currency debasement caused by the Peloponnesian war. So money debasement is as old as money itself. Traditionally, money debasement would involve issuers or traders ‘clipping’ tiny amounts of gold or silver from the coin, but still passing that coin on as though it was of a given weight. After a few rounds of clipping, your ounce of silver might only be worth nine tenths of an ounce of silver. Or maybe treasuries would mint gold or silver coins alloyed with base metals, again hoping that no one would notice. The intention was again to pass a coin containing less than an ounce of silver off as an ounce of silver and the effect would be an increase in the price level. Since more gold coins were needed to obtain a given amount of gold, more coins were also needed to buy given goods.

And why would people do this?

It’s important to understand that currency debasement is a mechanism for redistributing wealth. Anyone clipping coins kept the clippings for themselves and therefore secured an increase in their purchasing power. Any treasurer minting coins alloying gold or silver with copper or tin similarly benefitted because they now had more coins. Since the twentieth century the dominant circulating currency has been paper money and more recently, electronic money. Currency debasements have taken different shapes and forms this century – from the hyperinflations of central Europe following WW1 to the credit inflations of the 1920s or 2000s – but the fundamental principle has remained the same: the supply of money was increased in a way which redistributed societies’ wealth towards the issuer of the new money and away from everyone else.

What is the Cantillon effect?

Cantillon observed that when precious metals were imported into Spain and Europe from the New World in the sixteenth century causing a general price increase, the gold miners – the money creators, in other words – and those associated with them benefitted. When they spent their new found wealth on goods like meat, wine, or wool the prices of meat, wine and wool would rise as would the incomes of anyone involved in the production of those goods. For this group, money creation was highly beneficial. The problems arise for other groups. Anyone not involved in the production of money or of the goods the newly produced money purchased, but who nevertheless consumed them – a journalist or a nurse, for example – would find that the prices of those goods had risen while their incomes hadn’t. In other words, their real incomes had declined. Cantillon, writing before the days of Adam Smith, was the first to articulate it. I find it very puzzling that this insight has been ignored by the economics profession. Economists generally assume that money is neutral. And Milton Friedman’s allegory about the helicopter drop of money raising the general price level completely ignores the question of who is standing under the helicopter.

Why do governments debase money?

Governments usually raise revenue through taxation which has the benefit of being transparent and open. Everyone knows why they are poorer and by how much. They know who the perpetrator is, if you like. But raising money by simply creating it, debasing the existing currency stock is very different. For the government, the effect is the same. Whether printing money today, or clipping coin in the past, the debasement represents a real increase in government revenues and therefore purchasing power. But it’s better increasing in tax revenues because you can pretend you’re not actually raising taxes. You can hide what you’re doing. By printing one billion dollars, it now has one billion dollars more to spend without having to be open about what you’ve done. But we know that revenue cannotbe raised without someone somewhere paying. And here is the problem such an action creates: who pays?

Who pays?

The answer is that no one knows who or by how much. Most people are completely unaware that they are even being taxed. Keynes said that inflation redistributed wealth arbitrarily and in a way in which “not one man in a million is able to diagnose.” All people see is that they are suffering a decline in their own purchasing power. They can’t afford to buy the things they used to buy. They know something is wrong but they don’t know why. And they don’t who to blame. They don’t know who the perpetrator of this wrong they’re suffering is, so the group dynamic unleashes suspicion and speculation just like it does in Agatha Christies novels.

Could you explain that in detail?

Unfortunately, things being more complex in the real world than in whodunit novels, the group finds someone to blame. But there does seem to be a coincidence of past currency debasements with past social debasements in which society looks for an enemy to blame for its problems. History is replete with Great Disorders in which social cohesion has been undermined by currency debasements. The multi-decade credit inflation can now be seen to have had similarly corrosive effects. Yet central banks continue down the same route. The writing is on the wall. Further debasement of money will cause further debasement of society. I fear a Great Disorder.

Can you give us an example?

In medieval Europe, for example, the seventeenth century currency debasements coincided with the peak in witch trials. During the French (and Russian revolutions), rapidly debased currency coincided with the revolution’s transition from a representative movement to one which becomes bloody and self-consuming. The hyperinflations in Central Europe after WW1, most infamously in Weimar Germany but also in Austria and Hungary saw societies turning viciously on their Jewish communities. In Zimbabwe more recently, the white farmers were made scapegoats for the country’s ills and in Venezueala today, Chavez blames “profiteers” variously defined.

What sort of great disorder do you expect to play out in the days and years to come?

Although what we’ve seen in the last few decades has been an unprecedented credit inflation, which is a different type of currency debasement to the monetisations of the past or quantitative easing of today, today’s problems have the hallmarks of past inflations. So we see Cantillon redistributions in the very sudden increase in wealth inequality which has favoured those closest to the money creation (the financial sector and anyone with access to cheap credit). Everyone else has suffered. Median US household incomes have stagnated during the past twenty years while there is a record number of US households on foodstamps.

That’s a fair point…

We also see the in-group trust turn to suspicion as societies look for someone to blame. The 99% blame the 1%, the 1% blame the 47%, the public sector blame the private sector, and private sector blames the public sector. In the Eurozone the Northern Europeans blame the Southern Europeans, Germans blame Greeks, Greeks blame bankers. In Spain, the Catalans blame the Castillians and want independence. Meanwhile in China, popular anger seems to be deliberately directed by the Party towards the Japanese. So everywhere you look, everyone is blaming everyone else for the overall malaise. But that malaise is really just a consequence of the various credit inflations each of those societies experienced. The US, China, Spain, Greece etc all experienced one way or another, quite extreme credit inflations. In all of this I just think we’re seeing the usual debasement of society we might expect following a currency debasement.

But the money printing isn’t stopping…

The central banks’ solution to these problems is to print more money. But I think this solution is actually the problem. I understand why they’re doing it, and I appreciate what a difficult situation they find themselves in. But since these problems have been cause by their past currency debasement – asset price inflation engineered by credit inflation – I don’t see why another round of more traditional currency debasement is going to heal anything. I hope I’m wrong by the way, but I’m worried that this is the beginning of a Great Disorder in which social frictions increase. I’m concerned that distrust deepens both within societies and between them and inflation ultimately becomes uncontrollable. Obviously, financial markets reflect an environment like this, the financial analogue to less trust being higher yield. So I think the historically low yields we see today in bond, equity and real estate markets will go much higher. Of course, that implies their prices go much lower.

A shorter version of the interview appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on November 12, 2012.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

How Obama and Manmohan Singh will drive up the price of gold

Vivek Kaul

‘Miss deMaas,’ Van Veeteren decided, ‘if there’s anything I’ve learned in this job, it’s that there are more connections in the world than there are particles in the universe.’

He paused and allowed her green eyes to observe him.

‘The hard bit is finding the right ones,’ he added. – Chief Inspector Van Veeteren in Håkan Nesser’s The Mind’s Eye

I love reading police procedurals, a genre of crime fiction in which murders are investigated by police detectives. These detectives are smart but they are nowhere as smart as Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot or Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes. They look for clues and the right connections, to link them up and figure out who the murderer is.

And unlike Poirot or Holmes they take time to come to their conclusions. Often they are wrong and take time to get back on the right track. But what they don’t stop doing is thinking of connections.

Like Chief Inspector Van Veeteren, a fictional character created by Swedish writer Håkan Nesser, says above “there are more connections in the world than there are particles in the universe… The hard bit is finding the right ones.”

The murder is caught only when the right connections are made.

The same is true about gold as well. There are several connections that are responsible for the recent rapid rise in the price of the yellow metal. And these connections need to continue if the gold rally has to continue.

As I write this, gold is quoting at $1734 per ounce (1 ounce equals 31.1 grams). Gold is traded in dollar terms internationally.

It has given a return of 8.4% since the beginning of August and 5.2% since the beginning of this month in dollar terms. In rupee terms gold has done equally well and crossed an all time high of Rs 32,500 per ten grams.

So what is driving up the price of gold?

The Federal Reserve of United States (the American central bank like the Reserve Bank of India in India) is expected to announce the third round of money printing, technically referred to as quantitative easing (QE). The idea being that with more money in the economy, banks will lend, and consumers and businesses will borrow and spend that money. And this in turn will revive the slow American economy.

Ben Bernanke, the current Chairman of the Federal Reserve, has been resorting to what investment letter writer Gary Dorsch calls “open mouth operations” i.e. dropping hints that QE III is on its way, for a while now. The earlier two rounds of money printing by the Federal Reserve were referred as QE I and QE II. Hence, the expected third round is being referred to as QE III.

At its last meeting held on July 31-August 1, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) led by Bernanke said in a statement “The Committee will closely monitor incoming information on economic and financial developments and will provide additional accommodation as needed to promote a stronger economic recovery and sustained improvement in labor market conditions in a context of price stability.” The phrase to mark here is additional accommodation which is a hint at another round of quantitative easing. Gold has rallied by more than 8% since then.

But that was more than a month back. Ben Bernanke has dropped more hints since then. In a speech titled Monetary Policy since the Onset of the Crisis made at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, on August 31, 2012, Bernanke, said: “Taking due account of the uncertainties and limits of its policy tools, the Federal Reserve will provide additional policy accommodation as needed to promote a stronger economic recovery and sustained improvement in labor market conditions in a context of price stability.”

Central bank governors are known not to speak in language that everybody can understand. As Alan Greenspan, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve before Bernanke took over once famously said ““If you think you understood what I was saying, you weren’t listening.”

But the phrase to mark in Bernanke’s speech is “additional policy accommodation” which is essentially a euphemism for quantitative easing or more printing of dollars by the Federal Reserve.

The question that crops up here is that FOMC in its August 1 statement more or less said the same thing. Why didn’t that statement attract much interest? And why did Bernanke’s statement at Jackson Hole get everybody excited and has led to the yellow metal rising by more than 5% since the beginning of this month.

The answer lies in what Bernanke said in a speech at the same venue two years back. “We will continue to monitor economic developments closely and to evaluate whether additional monetary easing would be beneficial. In particular, the Committee is prepared to provide additional monetary accommodation through unconventional measures if it proves necessary, especially if the outlook were to deteriorate significantly,” he said.

The two statements have an uncanny similarity to them. In 2010 the phrase used was “additional monetary accommodation”. In 2012, the phrase used became “additional policy accommodation”.

Bernanke’s August 2010 statement was followed by the second round of quantitative easing or QE II as it was better known as. The Federal Reserve pumped in $600billion of new money into the economy by printing it. Drawing from this, the market is expecting that the Federal Reserve will resort to another round of money printing by the time November is here.

Any round of quantitative easing ensures that there are more dollars in the financial system than before. To protect themselves from this debasement, people buy another asset; that is, gold in this case, something which cannot be debased. During earlier days, paper money was backed by gold or silver. When governments printed more paper money than they had precious metal backing it, people simply turned up with their paper at the central bank and demanded it be converted into gold or silver. Now, whenever people see more and more of paper money, the smarter ones simply go out there and buy that gold. Also this lot of investors doesn’t wait for the QE to start. Any hint of QE is enough for them to start buying gold.

But why is the Fed just dropping hints and not doing some real QE?

The past two QEs have had the blessings of the American President Barack Obama. But what has held back Bernanke from printing money again is some direct criticism from Mitt Romney, the Republican candidate against the current President Barack Obama, for the forthcoming Presidential elections.

“I don’t think QE-2 was terribly effective. I think a QE-3 and other Fed stimulus is not going to help this economy…I think that is the wrong way to go. I think it also seeds the kind of potential for inflation down the road that would be harmful to the value of the dollar and harmful to the stability of our nation’s needs,” Romney told Fox News on August 23.

Paul Ryan, Romney’s running mate also echoed his views when he said “Sound money… We want to pursue a sound-money strategy so that we can get back the King Dollar.”

This has held back the Federal Reserve from resorting to QE III because come November and chances are that Bernanke will be working with Romney and Obama. Romney has made clear his views on Bernanke by saying that “I would want to select someone new and someone who shared my economic views.”

So what are the connections?

So gold is rising in dollar terms primarily because the market expects Ben Bernanke to resort to another round of money printing. But at the same time it is important that Barack Obama wins the Presidential elections scheduled on November 6, 2012.

Experts following the US elections have recently started to say that the elections are too close to call. As Minaz Merchant wrote in the Times of India “Obama’s steady 3% lead over Romney has evaporated in recent opinion polls… Ironically, one big demographic slice of America’s electorate could deny Obama a second term as president: white men. Up to an extraordinary 75% of American Caucasian males, the latest opinion polls confirm, are likely to vote against Obama… the Republican ace is the white male who makes up 35% of America’s population. If three out of four white men, cutting across Democratic and Republican party lines, vote for Mitt Romney, he starts with a huge electoral advantage, locking up over 25% of the total electorate.” (You can read the complete piece here)

If gold has to continue to go up it is important that Obama wins. And for that to happen it is important that a major portion of white American men vote for Obama. While Federal Reserve is an independent body, the Chairman is appointed by the President. Also, a combative Fed which goes against the government is rarity. So if Mitt Romney wins the elections on November 6, 2012, it is unlikely that Ben Bernanke will resort to another round of money printing unless Romney changes his mind by then. And that would mean no more rallies gold.

But even all this is not enough

All the connections explained above need to come together to ensure that gold rallies in dollar terms. But gold rallying in dollar terms doesn’t necessarily mean returns in rupee terms as well. For that to happen the Indian rupee has to continue to be weak against the dollar. As I write this one dollar is worth around Rs 55.5. At the same time an ounce of gold is worth $1734. As we know one ounce is worth 31.1grams. Hence, one ounce of gold in rupee terms costs Rs96,237 (Rs 1734 x Rs 55.5). This calculation for the ease of simplicity does not take into account the costs involved in converting currencies or taxes for that matter.

If one dollar was worth Rs 60, then one ounce of gold in rupee terms would have cost around Rs 1.04 lakh. If one dollar was worth Rs 50, then one ounce of gold in rupee terms would have been Rs 86,700. So the moral of the story is that other than the price of gold in dollar terms it is also important what the dollar rupee exchange rate is.

So the ideal situation for the Indian investor to make money by investing in gold is that the price of gold in dollar terms goes up, and at the same time the rupee either continues to be at the current levels against the dollar or depreciates further, and thus spruces up the overall return.

For this to happen Manmohan Singh has to keep screwing the Indian economy and ensure that foreign investors continue to stay away. If foreign investors decide to bring dollars into India then they will have to exchange these dollars for rupees. This will increase the demand for the rupee and ensure that it apprecaits against the dollar. This will bring down the returns that Indian investors can earn on gold. As we saw earlier at Rs60to a dollar one ounce of gold is worth Rs 1.04 lakh, but at Rs 50, it is worth Rs 86,700.

One way of keeping the foreign investors away is to ensure that the fiscal deficit of the Indian government keeps increasing. And that’s precisely what Singh and his government have been doing. At the time the budget was presented in mid March, the fiscal deficit was expected to be at 5.1% of GDP. Now it is expected to cross 6%. As the Times of India recently reported “The government is slowly reconciling to the prospect of ending the year with a fiscal deficit of over 6% of gross domestic project,higher than the 5.1% it has budgeted for, due to its inability to reduce subsidies, especially on fuel.

Sources said that internally there is acknowledgement that the fiscal deficit the difference between spending and tax and non-tax revenue and disinvestment receipts would be much higher than the calculations made by Pranab Mukherjee when he presented the Budget.” (You can read the complete story here).

To conclude

So for gold to continue to rise there are several connections that need to come together. Let me summarise them here:

1. Ben Bernanke needs to keep hinting at QE till November

2. Obama needs to win the American Presidential elections in November

3. For Obama to win the white American male needs to vote for him

4. If Obama wins,Bernanke has to announce and carry out QE III

5. With all this, the rupee needs to maintain its current level against the dollar or depreciate further.

6. And above all this, Manmohan Singh needs to keep thinking of newer ways of pulling the Indian economy down

(The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on September 11,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/how-obama-and-manmohan-will-drive-up-the-price-of-gold-450440.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])