Vivek Kaul

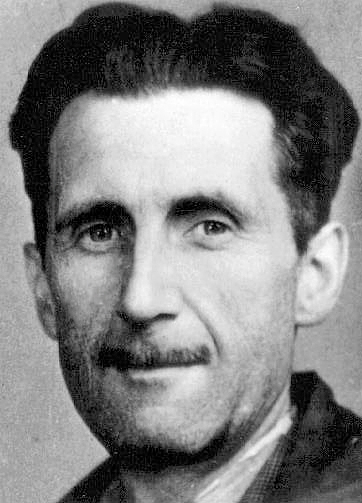

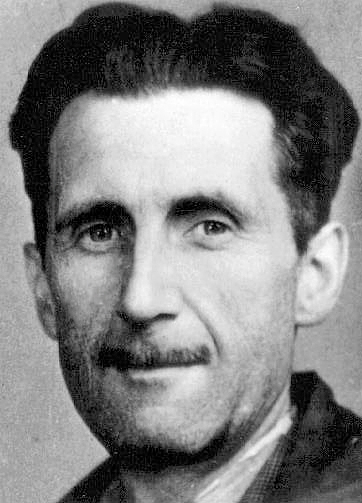

The writer George Orwell in his dystopian novel 1984 came up with the concept of “doublethink”. He defined this as a situation where people hold “simultaneously two opinions which cancelled out, knowing them to be contradictory and believing in both of them”. Arvind Subramanian, the chief economic adviser to the ministry of finance, seems to be in a similar situation these days. While speaking to the press after the Mid Year Economic Analysis was presented to the Parliament, Subramanian said that the government should consider increasing public sector spending in the medium term to revive economic growth . At the same time Subramanian said that the government was committed to meeting the fiscal deficit target of 4.1% of GDP during the current financial year. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends. How is it possible to stand for two absolutely opposite ideas at the same time? How can there be a commitment to increased government spending and maintaining the fiscal deficit at the same time? If the government spends more without earning more, its fiscal deficit is bound to go up. Nevertheless, before getting into this issue in detail let’s try and understand why Subramanian makes a case for increased public investment. In the Mid Year Economic Analysis Subramanian suggests that the public private partnership (PPP) model for infrastructure development hasn’t really worked. “There are stalled projects to the tune of Rs 18 lakh crore (about 13 percent of GDP) of which an estimated 60 percent are in infrastructure. In turn, this reflects low and declining corporate profitability as more than one-third firms have an interest coverage ratio of less than one (borrowing is used to cover interest payments). Over-indebtedness in the corporate sector with median debt-equity ratios at 70 percent is amongst the highest in the world. The ripples from the corporate sector have extended to the banking sector where restructured assets are estimated at about 11-12 percent of total assets. Displaying risk aversion, the banking sector is increasingly unable and unwilling to lend to the real sector,” the Mid Year Economic Analysis points out. What this means is that over the last few years corporates have borrowed more than what they can hope to repay. This has led to them defaulting and banks ending up in a mess. Currently the corporates are not willing to invest and banks are not ready to lend. In the process projects worth Rs 18 lakh crore (which is slightly more than the annual budget of the government of India) have been stalled. So what is the way out of this mess? “First, the backlog of stalled projects needs to be cleared more expeditiously, a process that has already begun. Where bottlenecks are due to coal and gas supplies, the planned reforms of the coal sector and the auctioning of coal blocks de-allocated by the Supreme Court as well as the increase in the price of gas which should boost gas supply, will help. Speedier environmental clearances, reforming land and labour laws will also be critical,” the analysis points out. But even this will not be enough, given that the PPP model hasn’t really delivered. In this scenario Subramanian suggests that “it seems imperative to consider the case for reviving public investment as one of the key engines of growth going forward, not to replace private investment but to revive and complement it.” The question that crops up here is on what should the government be spending money on? Subramanian suggests “there may well be projects for example roads, public irrigation, and basic connectivity–that the private sector might be hesitant to embrace.” He further suggests that one of the main lessons from PPP not working is that “India’s weak institutions there are serious costs to requiring the private sector taking on project implementation risks.” Hence, risks like “delays in land acquisition and environmental clearances, and variability of input supplies (all of which have led to stalled projects) are more effectively handled by the public sector.” And above all weak infrastructure (lack of power supply and poor connectivity) remains a major reason as to why the manufacturing sector hasn’t taken off in India. Increased spending by the government could address all these issues. The reasons presented by Subramanian for increased government spending make sense. One cannot argue against them. Nevertheless, he doesn’t address the most important question, which is, where is the money for all this going to come from? All he says in Mid Year Economic Analysis is that: “consideration should be given to address the neglect of public investment in the recent past and also review medium term fiscal policy to find the fiscal space for it(Italics in the original).” What he means here is that the government will have to somehow figure out how to finance the increased spending in the budgets to come. A document which runs into 148 pages could have done slightly better than that. So, let’s look at the options that the government has? It is not in a position to raise the tax rates, given the economic scenario that we are in. The other possible option is to cut down on non-plan expenditure which makes up for around 68% of the total expenditure of the government and use the money saved to increase public spending. Interest payments on debt, pensions, salaries, subsidies and maintenance expenditure are all non-plan expenditure. As is obvious a lot of non-plan expenditure is largely regular expenditure that cannot be done away with. The government needs to keep paying salaries, pensions and interest on debt, on time. Hence, slashing this expenditure is easier said than done. Another option for the government is to sell its assets, put that money into some sort of an infrastructure fund and use that money to finance higher public spending. But as we have seen over the last few years the disinvestment process has been a non starter. Now that leaves the government with only one option i.e. to finance the higher expenditure by borrowing more. This will lead to several other issues. As T N Ninan writes in the Business Standard: “The government could borrow more and invest, but the history of public sector investment is that, outside of sectors like oil marketing, the return on capital employed is lower than the government’s cost of borrowing.” While return on capital employed is not the best way to judge increased public spending, there are other issues that need to thought through as well. The government of India had managed to push its fiscal deficit down to 2.7% of GDP in 2007-2008. In 2008-2009, it decided to start increasing its expenditure to finance social schemes like NREGA and to give out subsidies as well. This pushed up the fiscal deficit to 6.4% of the GDP in 2009-10. This increased spending by the government helped the country grow at greater than 8% during a time when growth was collapsing all around the world in the aftermath of the financial crisis which started in September 2008. But it also led to a scenario of high interest rates and inflation, and a huge fall in household financial savings. The household financial savings have fallen dramatically over the last few years. The household financial savings rate was at 7.2% of the gross domestic product in 2013-2014, against 7.1% of GDP in 2012-2013 and 7% in 2011-2012. It had stood at 12% in 2009-2010. Household financial savings is essentially the money invested by individuals in fixed deposits, small savings scheme, mutual funds, shares, insurance etc. A fall in these savings led to high interest rates. The government was not creating any physical infrastructure through this increased spending. It was basically doling out money to asection of the population. As this money chased the same amount of goods and services it led to high inflation. Subramanian’s plan on the other hand is to use the increased government spending to create some physical infrastructure. Hence, increased government spending will not directly translate into inflation, as was previously the case. Nevertheless, all government spending in India has leakages and these leakages are likely to lead to some inflation. Further, there has been sharp fall in productivity over the last couple of years. As Swaminathan Aiyar puts it in his today’s column in The Economic Times: “After 2012, the investment needed to produce one unit of output has gone up from four to seven units.” Long story short—these issues need to be thought through. Further, an increase in spending can push up fiscal deficit again to a level, which the international rating agencies as well as foreign investors may not like. If the rating agencies downgrade India or even threaten to downgrade India that will lead to a huge amount of foreign money leaving the debt and the equity market. If the foreign investors see the Indian fiscal deficit going out of control they can also choose to exit India. This will lead to the rupee falling to levels which are not health for the Indian economy. And since we import more than we export any fall in the value of the rupee tends to hurt us more. This is something that the country went through only last year, and it should not be so forgotten so quickly. Even if a part of the money invested in the debt market starts to leave the country, the rupee will crash against the dollar. This is precisely what happened between June and November 2013, when foreign institutional investors sold debt worth Rs 78,382.2 crore. The rupee crashed to almost 69 to a dollar. Over the last five years economists and columnists have been complaining about a high fiscal deficit, high interest rates and high inflation. A major part of this came out because of the huge jump in government spending starting in mid 2008. Ironically, the same guys are now recommending that the government needs to increase its spending to create economic growth. In fact, this noise is only going to get louder in the new year. What this tells us is that economists and columnists (who also fancy themselves as economists) basically have two ides: cut interest rates (an idea which came from Milton Friedman) and increase government spending (an idea which came from John Maynard Keynes). These two ideas keep repeating themselves in cycles. And now that Raghuram Rajan hasn’t obliged with an interest rate cut, the economists have jumped on to the increasing public spending idea. A version of the second idea is when the government decides to increase spending through printing money. The conspiracy theory going around is that is exactly what the government may be planning. Meanwhile, I am waiting for the day when an economist comes up with a third idea. The column appeared on www.equitymaster.com as a part of The Daily Reckoning, on December 23, 2014