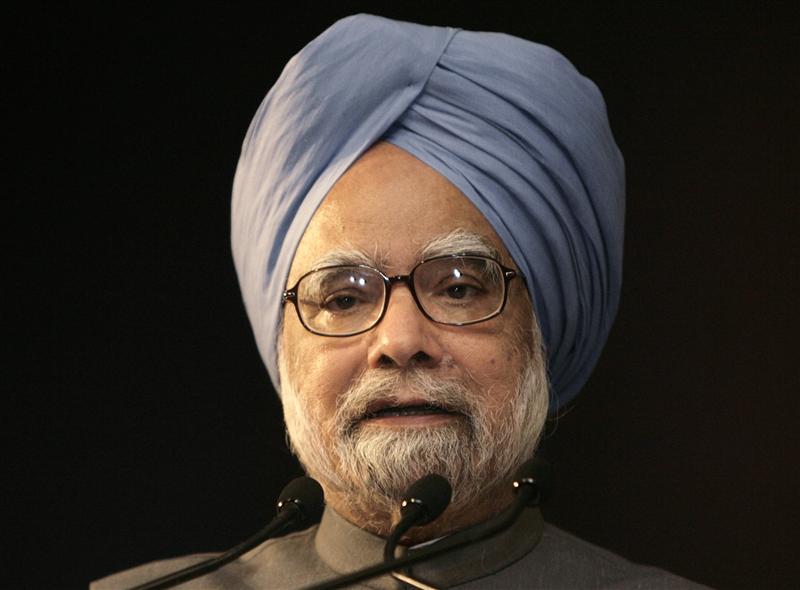

In January 2014, towards the end of his second term, Manmohan Singh spoke to the media for the third time in a decade. On this occasion he said “I honestly believe that history will be kinder to me than the contemporary media.”

While speaking to the media Singh also said “I feel somewhat sad, because I was the one who insisted that spectrum allocation should be transparent, it should be fair, it should be equitable. I was the one who insisted that coal blocks should be allocated on the basis of auctions. These facts are forgotten.”

If that was the case then why did the allocation of 2G(second generation) telecom licenses and coal blocks end up in a mess? This Singh did not elaborate on during the course of his interaction with the media in January, earlier this year. Neither has he chosen to elaborate on these points since then.

Vinod Rai, the former Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG), analyses both these issues and the role Singh played in them, threadbare, in his new book Not Just an Accountant—The Diary of the Nation’s Conscience Keeper. In this piece we shall look at the mess that the issuance of 2G telecom licenses ended up in and leave the discussion on what came to be called coalgate, for sometime later this week.

Rai in his book through a series of documented evidence shows how Singh was fully aware of what was going on, but still chose to not to do anything about it. Instead, he even went to the extent of distancing himself from the decisions made by the communications minister A Raja.

As Rai writes “You [Manmohan Singh] engaged in a routine and ‘distanced’ handling of the entire allocation process, in spite of the fact that the then communications minister A Raja, had indicated to you, in writing, the action he proposed to take. Insistence on the process being fair could have prevented the course of events during which canons of financial propriety were overlooked, unleashing what probably is the biggest scam in the history of Independent India.”

Before we get into the details of what probably led Rai to make such a strong statement, we need to take a brief look at how the Indian telecom sector evolved from the 1990s.

The telecom sector was opened up to the private players in a phased manner after the announcement of the National Telecom Policy (NTP) in 1994. Licenses were initially allotted to private companies in 1995, through the competitive bidding route. These licenses allowed private companies to launch mobile phone telephony in India.

The policy was revised in 1999 and existing mobile phone operators were allowed to migrate to a revenue sharing regime with the government. “The upfront payment was an entry fee, with the annual license fee to be paid separately. The entry fee was fixed on the basis of the highest bid received in the 2001 auction of licenses. It was Rs 1,651 crore for pan-India licenses,” writes Rai. The then prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee constituted a group of ministers on telecom in September 2003. The recommendations of this group were added to the National Telecom Policy of 1999. The existing system of issuing licenses were replaced by an automatic authorization regime.

A Raja took over as the communications minister in May 2007. He decided to continue with the first-come-first served(FCFS) policy for allocation of licenses to telecom companies. On September 25, 2007, a press release was issued and applications were invited for telecom licenses. The last date was set to October 1, 2007, a week later.

In total 575 applications for 22 service areas were received by the communications ministry. This led to the ministry of communications writing to the law ministry and sought its opinion on how to deal with the situation of so many applicants. The law ministry suggested that the issue be referred to the empowered group of ministers(eGOM). Raja did not like this suggestion and on November 1, 2007, wrote a letter to Manmohan Singh.

In this letter Raja complained that the suggestion of the law ministry “is totally out of context”. He then went on to coolly inform the prime minister that he had decided to advance the cut off date for licenses to September 25,2007, the date on which the press release was issued for the allocation of licenses, instead of October 1, 2007.

Raja further told Singh that “the procedure for processing the remaining applications will be decided at a later date, if any spectrum is left available after processing the applications received up to September 25, 2007.”

The rules of the game were changed after it had started. Singh responded immediately on the same day. In his letter, Singh seemed to be concerned over the fact that a large number of applications for new licenses had been received. Given the fact that the spectrum was limited, it would not be possible to give spectrum to all of them, even over the next few years, Singh wrote. He further pointed out that the National Telecom Policy of 1999 had specifically stated that the new licenses be issued subject to the availability of spectrum.

In this scenario, Singh suggested that the communications ministry consider the introduction of a transparent methodology of auction, wherever it was legally and technically feasible. This needed to be done in order to ensure that spectrum was used efficiently.

Also, the entry fee for these licenses was the same as in 2001, i.e. Rs 1,651 crore. Hence, Singh suggested that the entry fee be revised. This was a logical suggestion to make given that six years had passed since 2001 and if not anything at least inflation had to be taken into account.

Raja responded within hours of receiving this letter from Singh. He ruled out an auction stating that “the issue of auction of spectrum was considered by TRAI[the telecom regulator] and the telecom commission and was not recommended as the existing license holders..have got it without any spectrum charge.” Raja went on to add that the holding an auction would thus be “unfair, discriminatory, arbitrary and capricious”.

Meanwhile, Kamal Nath, wrote to Singh on November 3, 2007, and suggested that a group of ministers should be asked to comprehensively study all the issues facing the telecom sector. Raja responded to this on November 15, and said that the Indian telecom industry was doing very well and was adding seven million new customers every month. The shares of the telecom companies listed on the stock market were also doing very well. And given these reasons the suggestion of Kamal Nath of setting up a group of ministers was again “out of context,” as had been the case with the law ministry earlier.

Singh responded on November 21, by sending what former CAG Rai calls a “template response”. In this letter Singh acknowledged that he had received Raja’s recent letter on the recent developments in the telecom sector. Raja wrote to the prime minister again on December 26, 2007. Singh again responded with the same templated response on January 3,2008.

All that has been discussed till now raises a series of questions. As Rai writes “[Manmohan Singh] failed to direct his minister[i.e. A Raja] to follow his advice…Why under what compulsion, did the prime minister allow Raja to have his way, which permitted a finite national resource [i.e. the telecom spectrum] to be gifted at throwaway price to private companies—private companies that, going by the minister’s own admission, were ‘enjoying the best results […] which was also reflected in their increasing share prices?”

Also, why was the entry price fixed at Rs 1,651 crore, which was a price set way back in 2001. As mentioned earlier this price should have at least taken inflation into account. The telecom market had also expanded since 2001. The National Telecom Policy of 1999 had set a teledensity target of providing 15 telephone connections per 100 of population. The teledensity in 2001 had stood at 3.58. In September 2007, a teledensity of 18.22 had been reached. “Was this data not available with the government..to counter Raja’s consistent and constant refrain?” asks Rai.

Further, even if increasing teledensity was the main goal, given that the spectrum is finite, didn’t it call for a “balance between revenue generation and achieving social objectives?” In fact, the tenth plan document clearly mentions this, when it comes to spectrum allocation: “pricing needs to be based on relative demand and supply over space and time in a dynamic manner, [with] opportunity cost to reflect relative scarcity of the resource in a given situation.”

Also, why was the cut-off date for the last date to receive applications arbitrarily advanced from October 1, 2007 to September 25,2007? As Rai writes “Though Raja clearly indicated this to the prime minister in his letter of 2 November 2007, the PMO chose not to object. Why it chose not to, remains unclear.”

Interestingly, thirteen applicants seem to have known of this change in date, in advance. How else do you explain the fact that certain applicants appeared with demand drafts amounting to thousands of crore, which had been issued even before the press release inviting applications for telecom licenses was put out on September 25, 2007.

Then there is the question of first-come-first served. It essentially means those who applied for a license first, would be given a license first. But that wasn’t the case. “One would be surprised to learn that even this procedure, which was repeatedly reiterated to the prime minister by Raja, was given the go-by, and all applications submitted between March 26 and 25 September 2007 were considered together,” writes Rai.

Pulok Chatterjee, a bureaucrat known to be close to the Gandhi family, was an additional secretary in the prime minister’s office at that point of time. In a note that was presented to prime minister Singh on January 6, 2008, Chatterjee concluded that “ideally in a situation where the spectrum is scarce it should be auctioned”. But by that time the licenses had already been issued.

Joint secretary Vini Mahajan recorded that the prime minister wanted Chaterjee’s note to be only “informally shared within the Dept”. She further noted that the prime minister “does not want a formal communication and wants PMO to be at arm’s length.” As Rai asks “How can the office of the prime minister distance itself from such major decisions? Arm’s length from the action of his own government?”

Also, it needs to be noted here that Raja suggested that TRAI was against auction of telecom spectrum. This is untrue. In August 2007, the telecom regulator had clearly stated that: “In today’s dynamism and unprecedented growth of telecom sector, the entry fee determined in 2001 is also not the realistic price of obtaining a license. Perhaps it needs to be reassessed by a market mechanism.”

The companies which got these licenses cheap, cashed in on it almost immediately. “In case of Unitech, which had no previous experience in the telecom business, Telenor, a Norwegian company, agreed to acquire 67.25 per cent stake for Rs 6,120 crore. Tata Teleservices sold 27.31 per cent stake to NTT Docomo at a value of Rs 12,924 crore. Even Swan Telecom sold 44.73 per cent stake to Etisalat International at Rs 3,217 crore. Is that not clearly indicative of the value the market attached to the 2G spectrum license. Even a cursory back-of-the-envelope calculation will indicate that licenses which could have fetched between Rs 8,000 to Rs 9,000 crore were priced at Rs 1,658,” writes Rai.

On February 2, 2012, the Supreme Court cancelled all the licenses that had been issued by A Raja.

On a slightly different note, Rai also points out it was a ruling party MP (Rai does not give out his name in the book) who seems to have first suggested that losses that the government faced from giving out licenses cheaply, needed to be calculated.

As Rai puts it “He [i.e. the MP] went on to reiterate that it was obvious how much the government of India could have secured by transparent bidding and asserted that even a section officer in the government would be able to make this computation.” In a recent interview Rai revealed that the name of the MP was KS Rao, who has since quit the Congress protesting against the bifurcation of Andhra Pradesh and joined the BJP.

Rai writes that this was one of the reasons why the CAG decided to compute a loss figure arising out of the 2G telecom licenses being issued cheaply. As he writes “Now if an MP, and of the ruling party, makes such a strong assertion, obviously the audit department has to take cognizance of that parameter for computation.”

The CAG used various methods to compute a loss figure and arrived at a four numbers ranging from Rs 57,666 crore to Rs 1,76,645 crore. All this could have been avoided only if Singh had chosen to respond differently and instead said to Raja that “I have received your letter…Please do not precipitate any action till we or the GoM[group of ministers] have discussed this.”

To conclude, on an earlier occasion I had written that if he wants history to treat him kindly, Singh needs to write his autobiography and put forward his side of the story as well. Whether he does that or not, remains to be seen. But Vinod Rai’s thoroughly researched book makes me now believe that whatever Singh might do, history will not be kind to him, his hopes notwithstanding.

The article appeared originally on www.Firstpost.com on Sep 15, 2014

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)