Vivek Kaul

There’s nothing more thrilling than nailing an insurance company – Deck Shifflet (played by Danny DeVito) in The Rainmaker

Around three years back I suddenly got a call from my bank. “I am your relationship manager Sir,” the female voice at the other end said. “Since when did journalists start to have relationship managers,” was the first thought that came to my mind. It turned out she wanted to help me plan my finances.

Fair enough. But why did the bank have a sudden interest to plan my finances? I had been banking with them for close to four years and they hadn’t shown any such interest earlier. I checked my bank account and realised that there was a fair amount of cash lying around in my savings bank account. A friend had just repaid some money back and a fixed maturity plan which I had invested in had matured.

So the reason behind the bank’s sudden interest in planning my finances became clear to me. I asked my new relationship manager to come and meet me immediately. I was curious to see what financial plan she had in mind.

What she did not know was that my area of specialisation as a journalist was personal finance. The relationship manage soon turned up and within ten minutes she offered me the solution to all my financial problems in life, which as expected, turned out to be a unit linked insurance plan (Ulip).

The bank she worked for also has an insurance company and this particular Ulip was from that insurance company. I just checked the brochure she had brought along and was not surprised to find that the premium allocation charge for this Ulip for the first year was a whopping 60%. What this meant was that if I were to pay a premium of Rs 1 lakh, only Rs 40,000 would be actually invested. The remaining Rs 60,000 would be deducted as an expense.

A major part of the Rs 60,000 deducted as expense would be given to the insurance agent (in my case the bank) as commission. And it would help my relationship manager meet her rather stiff targets.

I pointed this out to my relationship manager and she realised that the game was over. I wouldn’t fall for her sales pitch. Then we got talking about other things and realised that we grew up in the same town. Before leaving she apologised for trying to sell me such a plan. She also told me that in the pressure to meet her target last year she had sold the same policy to her brother.

He had taken a policy with a premium of Rs 1 lakh of which Rs 40,000 had been invested. The stock markets had taken a beating since then and the value of the investment had fallen to Rs 32,000. “He doesn’t talk to me properly anymore,” she said, as she left with a tinge of regret in her voice.

Those were the heady days of mis-selling in insurance when even sisters sold Ulips to brothers so that they could earn a high commission and meet their targets. Since then commissions have been reduced and as a result the mis-selling has come down.

But if the finance minister P Chidambaram has his way with things,mis-selling is all set to return in the days to come. But before I get to that let me just share some numbers that the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority, the insurance regulator, has released in its September 2012 journal.

For the period April 1 to June 30, 2012, the insurance companies in India collected Rs 12015.5 crore as first year’s premium by selling around 67.9 lakh new policies. Given this the average premium per policy works out to around Rs 17,690 (Rs 12015.5 crore divided by 67.9 lakh).

The total sum assured (or what is in general terms referred to as a life cover i.e. essentially the money the nominee will get if the policyholder dies) on these policies was Rs 1,50.902.8 crore. So the average life cover per policy works out to around Rs 2.22 lakh (Rs 1,50,902.8crore divided by 67.9lakh).

Hence, for the first quarter of 2012, the average premium on a life insurance policy was Rs 17,690 and it had an average life cover of Rs 2.22 lakh. If a 35 year old were to just buy a pure life cover of Rs 2.22 lakh, the premium works out to around Rs 500-700 per year on a 25 year policy. Assuming that a pure life cover of Rs 2.22 lakh can be bought for a premium of Rs 700 per year that would mean a premium of Rs 17,000 is left over.

And this is the amount that is invested by insurance companies after deducting the commission paid. In the year 2010-2011(i.e. between April 1, 2010 and March 31, 2011), the average commission paid on the first year premium was 8.89%. This is the latest data that is available.

Assuming this to be rate of commission, the commission on a premium of Rs 17,690 works out to Rs 1573 (8.89% of Rs 17,690). Deducting this from Rs 17,000, around Rs 15,417 is left over. This is the amount that is invested depending upon the mandate chosen by the policyholder which could vary from 100% stocks to 100% debt.

So what this basically tells us is that Indian insurance companies do not sell life insurance, they sell high commission paying mutual funds. As my calculations show less than 4% (Rs 700 expressed as a % of Rs 17,690) of the total premium goes towards actual insurance. Around 9% is paid as commission and the remaining amount is invested depending on the mandate given by the policy holder.

The finance minister P Chidambaram now wants to encourage the sales of these high cost mutual funds masquerading as insurance policies. He is in the process of offering a series of sops to insurance companies so that they can sell more. Among the proposed sops are greater tax deductions on insurance premiums, banks being allowed to sell insurance policies of more than one insurance company etc.

This is being done so that insurance companies are able to sell more policies and in the process more money from the domestic investors is channelised into the stock market. Since the beginning of the year domestic institutional investors have sold stocks worth around Rs 38,475 crore. The government wants to turn this tide in order to ensure that the stock market continues to go up.

This is very important if the government hopes to divest its stake in a lot of public sector companies. The disinvestment target for the year is Rs 30,000 crore. But a lot more shares will have to be sold if the government wants to control the burgeoning fiscal deficit. (you can read a detailed argument on this here).

So the higher the stock market goes the more the number of shares that the government will be able to sell. And for that happen more and money from domestic investors needs to come into the stock market. And that will only happen if the insurance companies are able to sell more policies.

As anybody who does not make money selling insurance policies or is honest enough, will tell you that mutual funds remain a better investment option. So the question that crops up here is why does Chidambaram want to encourage only insurance companies to sell more and not mutual funds?

Mutual funds are much more transparent. There performance when it comes to generating returns is much better than insurance companies. They don’t pay 9% commissions to their agents. And it is very easy to figure out which are the best mutual funds going around in the market. I haven’t seen anybody who makes a living out of selling insurance talk about returns generated by insurance policies till date.

There are a couple of reasons for Chidambaram encouraging insurance companies and not mutual funds. One is that commission offered by mutual funds is very low compared to the commission offered by insurance companies. Hence, agents of all kinds prefer to sell insurance rather than mutual funds. Chidambaram needs a lot of money to enter the stock market and he needs it to come quickly. That being the case, it’s easier for insurance companies to do this than mutual funds.

The second and more important reason is the fact that Life Insurance Corporation(LIC) of India which is India’s biggest insurance company, is government run. Between April and July of this financial year LIC collected 76.5% of the total first year’s premium. So three fourths of insurance in India is basically LIC.

The money collected by LIC can be directed by the government into specific stocks. If the stock market does not how enough interest in shares of a company being divested by the government, LIC can be instructed to pick up those shares.

If Chidambaram had encouraged mutual funds instead of insurance companies he wouldn’t have had this flexibility. So once these measures to help insurance companies are pushed through, insurance companies and agents will be back to doing what they do best i.e. mis-sell. Don’t be surprised if in the days to come you run into insurance agents promising you the moon, from your investment doubling in three years to you having to pay premiums only for five years.

And in this case this renewed attempt at mis-selling will be a result of the Finance Minister P Chidambaram encouraging insurance at the cost of mutual funds. The more insurance agents mis-sell, the greater will be the money invested in the stock market which will lead to the stock markets rallying and thus help the government sell more shares than it had originally planned.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on October 5, 2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/why-chiddu-wants-insurance-agents-to-mis-sell-480473.html

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

LIC

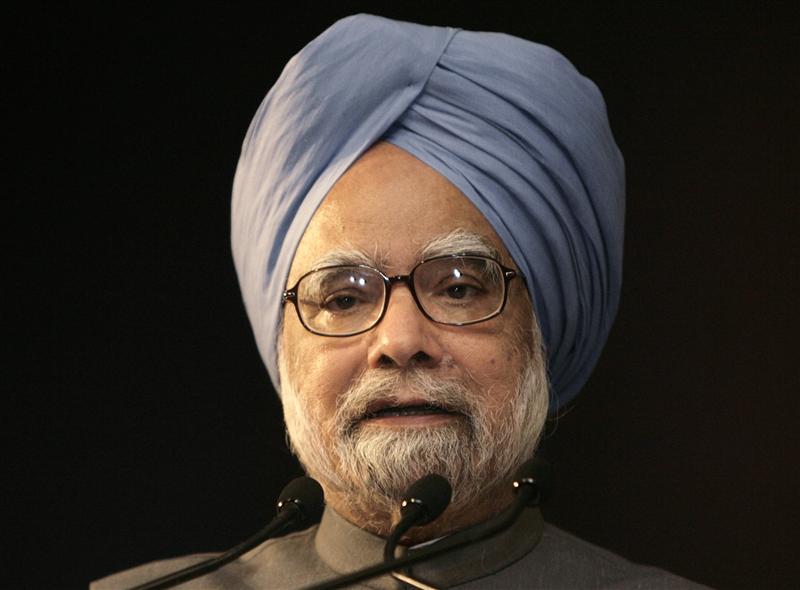

Why Manmohan Singh was better off being silent

Vivek Kaul

So the Prime Minister (PM) Manmohan Singh has finally spoken. But there are multiple reasons why his defence of the free allocation of coal blocks to the private sector and public sector companies is rather weak.

“The policy of allocation of coal blocks to private parties…was not a new policy introduced by the UPA (United Progressive Alliance). The policy has existed since 1993,” the PM said in a statement to the Parliament yesterday.

But what the statement does not tell us is that of the 192 coal blocks allocated between 1993 and 2009, only 39 blocks were allocated to private and public sector companies between 1993 and 2003.

The remaining 153 blocks or around 80% of the blocks were allocated between 2004 and 2009. Manmohan Singh has been PM since May 22, 2004. What makes things even more interesting is the fact that 128 coal blocks were given away between 2006 and 2009. Manmohan Singh was the coal minister for most of this period.

Hence, the defence of Manmohan Singh that they were following only past policy falls flat. Given this, giving away coal blocks for free is clearly UPA policy. Also, we need to remember that even in 1993, when the policy was first initiated a Congress party led government was in power.

The PM further says that “According to the assumptions and computations made by the CAG, there is a financial gain of about Rs. 1.86 lakh crore to private parties. The observations of the CAG are clearly disputable.”

What is interesting is that in its draft report which was leaked earlier in March this year, the Comptroler and Auditor General(CAG) of India had put the losses due to the free giveaway of coal blocks at Rs 10,67,000 crore, which was equal to around 81% of the expenditure of the government of India in 2011-2012.

Since then the number has been revised to a much lower Rs 1,86,000 crore. The CAG has arrived at this number using certain assumptions.

The CAG did not consider the coal blocks given to public sector companies while calculating losses. The transaction of handing over a coal block was between two arms of the government. The ministry of coal and a government owned public sector company (like NTPC). In the past when such transactions have happened revenue from such transactions have been recognized.

A very good example is when the government forces the Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) of India to forcefully buy shares of public sector companies to meet its disinvestment target. One arm of the government (LIC) is buying shares of another arm of the government (for eg: ONGC). And the money received by the government is recognized as revenue in the annual financial statement.

So when revenues from such transactions are recognized so should losses. Hence, the entire idea of the CAG not taking losses on account of coal blocks given to pubic sector companies does not make sense. If they had recognized these losses as well, losses would have been greater than Rs 1.86lakh crore. So this is one assumption that works in favour of the government. The losses on account of underground mines were also not taken into account.

The coal that is available in a block is referred to as geological reserve. But the entire coal cannot be mined due to various reasons including those of safety. The part that can be mined is referred to as extractable reserve. The extractable reserves of these blocks (after ignoring the public sector companies and the underground mines) came to around 6282.5 million tonnes. The average benefit per tonne was estimated to be at Rs 295.41.

As Abhishek Tyagi and Rajesh Panjwani of CLSA write in a report dated August 21, 2012,”The average benefit per tonne has been arrived at by first, taking the difference between the average sale price (Rs1028.42) per tonne for all grades of CIL(Coal India Ltd) coal for 2010-11 and the average cost of production (Rs583.01) per tonne for all grades of CIL coal for 2010-11. Secondly, as advised by the Ministry of Coal vide letter dated 15 March 2012 a further allowance of Rs150 per tonne has been made for financing cost. Accordingly the average benefit of Rs295.41 per tonne has been applied to the extractable reserve of 6282.5 million tonne calculated as above.”

Using this is a very conservative method CAG arrived at the loss figure of Rs 1,85,591.33 crore (Rs 295.41 x 6282.5million tonnes).

Manmohan Singh in his statement has contested this. In his statement the PM said “Firstly, computation of extractable reserves based on averages would not be correct. Secondly, the cost of production of coal varies significantly from mine to mine even for CIL due to varying geo-mining conditions, method of extraction, surface features, number of settlements, availability of infrastructure etc.”

As the conditions vary the profit per tonne of coal varies. To take this into account the CAG has calculated the average benefit per tonne and that takes into account the different conditions that the PM is referring to. So his two statements in a way contradict each other. Averages will have been to be taken into consideration to account for varying conditions. And that’s what the CAG has done.

The PM’s statement further says “Thirdly, CIL has been generally mining coal in areas with

better infrastructure and more favourable mining conditions, whereas the coal blocks offered for captive mining are generally located in areas with more difficult geological conditions.”

Let’s try and understand why this statement also does not make much sense. As The Economic Times recently reported, in November 2008, the Madhya Pradesh State Mining Corporation (MPSMC) auctioned six mines. In this auction the winning bids ranged from a royalty of Rs 700-2100 per tonne.

In comparison the CAG has estimated a profit of only Rs 295.41 per tonne from the coal blocks it has considered to calculate the loss figure. Also the mines auctioned in Madhya Pradesh were underground mines and the extraction cost in these mines is greater than open cast mines. The profit of Rs 295.41was arrived at by the CAG by considering only open cast mines were costs of extraction are lower than that of underground mines.

The fourth point that the PM’s statement makes is that “Fourthly, a part of the gains would in any case get appropriated by the government through taxation and under the MMDR Bill, presently being considered by the parliament, 26% of the profits earned on coal mining operations would have to be made available for local area development.”

Fair point. But this will happen only as and when the bill is passed. And CAG needs to work with the laws and regulations currently in place.

A major reason put forward by Manmohan Singh for not putting in place an auction process is that “major coal and lignite bearing states like West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Orissa and Rajasthan that were ruled by opposition parties, were strongly opposed to a switch over to the process of competitive bidding as they felt that it would increase the cost of coal, adversely impact value addition and development of industries in their areas.”

That still doesn’t explain why the coal blocks should have been given away for free. The only thing that it does explain is that maybe the opposition parties also played a small part in the coal-gate scam.

To conclude Manmohan Singh might have been better off staying quiet. His statement has raised more questions than provided answers. As he said yesterday “Hazaaron jawabon se acchi hai meri khamoshi, na jaane kitne sawaalon ka aabru rakhe”.For once he should have practiced what he preached.

(The article originally appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on August 29,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/analysis/column_why-manmohan-singh-was-better-off-being-silent_1734007))

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

LIC money: Is it for investors’ benefit, or Rahul's election?

Vivek Kaul

“We’re slowly learning that fact. And we’re very, very pissed off.”

—Lines from the movie Fight Club

The government’s piggybank is in trouble. Well not major trouble. But yes some trouble.

The global credit rating agency Moody’s on Monday downgraded the Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) of India from a Baa2 rating to Baa3 rating. This is the lowest investment grade rating given by Moody’s. The top 10 ratings given by Moody’s fall in the investment grade category.

Moody’s has downgraded LIC due to three reasons: a) for picking up stake in the divestment of stocks like ONGC, when no one else was willing, to help the government reduce its fiscal deficit. b) for picking up stakes in a lot of public sector banks. c) having excessive exposure to bonds issued by the government of India to finance its fiscal deficit.

While the downgrade will have no impact on the way India’s largest insurer operates within India, it does raise a few basic issues which need to be discussed threadbare.

From Africa with Love

The wives of certain African dictators before going on a shopping trip to Europe used to visit the central bank of their country in order to stuff their wallets with dollars. The African dictators and their extended families used the money lying with the central banks of their countries as their personal piggybank. Whenever they required money they used to simply dip into the reserves at the central bank.

While the government of India has not fallen to a similar level there is no doubt that it treats LIC like a piggybank, rushing to it whenever it needs the money.

So why does the government use LIC as its piggybank? The answer is very simple. It spends more than what it earns. The difference between what the government earns and what it spends is referred to as the fiscal deficit.

In the year 2007-2008 (i.e. between April 1, 2007 and March 31,2008) the fiscal deficit of the government of India stood at Rs 1,26,912 crore. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what the government earns and what it spends. For the year 2011-2012 (i.e. between April 1, 2011 and March 31, 2012) the fiscal deficit is expected to be Rs 5,21,980 crore.

Hence the fiscal deficit has increased by a whopping 312% between 2007 and 2012. During the same period the income earned by the government has gone up by only 36% to Rs 7,96,740 crore. The expenses of the government have risen more than eight and half times faster than its revenues.

What is interesting is that the fiscal deficit numbers would have been much higher had the government not got LIC to buy shares of public sector companies it was selling to bring down the fiscal deficit.

Estimates made by the Business Standard Research Bureau in early March showed that LIC had invested around Rs 12,400 crore out of the total Rs 45,000 crore that the government had collected through the divestment of shares in seven public sector units since 2009. The value of these shares in March was around Rs 9,379 crore. Since early March the BSE Sensex has fallen 7.4%, which means that the LIC investment would have lost further value.

Over and above this the government also forced LIC to pick up 90% of the 5% follow-on offer from the ONGC in early March this year. This after the stock market did not show any interest in buying the shares of the oil major. The money raised through this divestment of shares went towards lowering the fiscal deficit of the government of India.

News reports also suggest that LIC was buying shares of ONGC in the months before the public issue of the insurance major hit the stock market, in an effort to bid up its price. Between December and March before the public offer, the government first got LIC to buy shares of ONGC and bid up the price of the stock from around Rs 260 in late December to Rs 293 by the end of February. After LIC had bid up the price of ONGC, the government then asked it to buy 90% of the shares on sale in the follow on public offer.

This is a unique investment philosophy where institutional investor managing money for the small retail investor, first bid up the price of the stock by buying small chunks of it, and then bought a large chunk at a higher price. Stock market gurus keep repeating the investment philosophy of “buy low-sell high” to make money in the stock market. The government likes LIC to follow precisely the opposite investment philosophy of “buying high”.

Estimates made by Business Standard suggest that LIC in total bought ONGC shares worth Rs 15,000 crore. The stock is since down more than 10%.

The bank bang

LIC again came to the rescue of the cash starved government during the first three months of this year, when it was force to buy shares of several government owned banks which needed more capital. It is now sitting on losses from these investments.

Take the case of Viajya Bank. It issued shares to LIC at a price of Rs 64.27 per share. Since then the price of the stock has fallen nearly 19%.

The same is case with Dena Bank. The stock price is down by almost 10% since allocation of shares to LIC. The share price of Indian Overseas Bank is down by almost 19.7% since it sold shares to LIC to boost its equity capital. While the broader stock market has also fallen during the period it hasn’t fallen as much as the stock prices of these shares have.

There are more than a few issues that crop up here. This special allotment of shares to LIC to raise capital has pushed up the ownership of LIC in many banks beyond the 10% mandated by the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India, the insurance regulator. As any investment professional will tell you that having excessive exposure one particular company or sector isn’t a good strategy, especially when managing money for the retail investor, which is what LIC primarily does. What is interesting is that the government is breaking its own laws and thus not setting a great precedent for the private sector.

If LIC hadn’t picked up the shares of these banks, the fiscal deficit of the government would have gone up further. The third issue here is why should the government run so many banks? The government of India runs twenty six banks (20 public sector banks + State Bank of India and its five subsidiaries).

While given that banking is a sensitive sector and some government presence is required, but that doesn’t mean that the government has to run 26 banks. It is time to privatise some of these banks.

Gentlemen prefer bonds

As of December 31, 2011, the ratio of government securities to adjusted shareholders’ equity in LIC was 764%. This is understandable given that the subsidy heavy budget of the Congress led UPA government has seen its fiscal deficit balloon by 312% over the last five years. Again basic investment philosophy tells us that having a large exposure to one investment isn’t really a great idea, even if it’s a government.

The Rahul factor

But the most basic issue here is the fact that the government is using the small savings of the average Indian who buys LIC policies to make loss making investments. This is simply not done.

LIC has turned into the behemoth that it has over the years by offering high commissions to its agents over the years. It sells very little of “term insurance”, the real insurance. What it basically sells are investment policies with very high expenses which are used to pay high commissions to it’s the agents. The high commissions in turn ensure that these agents continue to hard-sell LIC’s extremely high cost investment policies to normal gullible Indians. The premium keeps coming in and the government keeps using LIC as a piggybank.

The high front-loading of commissions is allowed by The Insurance Act, 1938. The commission for the first can be a maximum of 40 per cent of the premium. In years two and three, the caps are 7.5 per cent, and 5 per cent thereafter. These are the maximum caps and serve as a ceiling rather than a floor.

The Committee on Investor Protection and Awareness led by D Swarup, the then Chairman of Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority, had proposed in September 2009 to do away with commissions across financial products. “All retail financial products should go no-load by April 2011,” the committee had proposed in its reports.

The National Pension Scheme(NPS) was already on a no commission structure. And so were mutual funds since August 1, 2009. But LIC and the other insurance companies were allowed to pay high commissions to their agents. “Because there are almost three million small agents who will have to adjust to a new way of earning money, it is suggested that immediately the upfront commissions embedded in the premium paid be cut to no more than 15 per cent of the premium. This should fall to 7 per cent in 2010 and become nil by April 2011,” the committee had further proposed.

Not surprisingly the government quietly buried this groundbreaking report.

While insurance commissions have come down on unit linked insurance plans, the traditional insurance policies in which LIC remains a market leader continue to pay high commissions to their agents. These traditional insurance policies typically invest in debt (read government bonds which are issued to finance the fiscal deficit).

This is primarily because the Congress led UPA government needs the premium collected by LIC to run LIC like a piggybank. The piggybank money can and is being used to run subsidies in the hope that the beneficiaries vote for Rahul Gandhi in 2014.

Is the objective of LIC to generate returns and ensure the safety of the hard earned money of crores of it’s investors? Or is it to let the UPA government run it like a piggybank in the hope that Rahul baba becomes the Prime Minister?

The country is waiting for an answer.

(This post originally appeared on Firstpost.com on May 15,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/politics/lic-money-is-it-for-investors-benefit-or-rahul-election-309545.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])