If you shout loud enough someone is bound to hear.

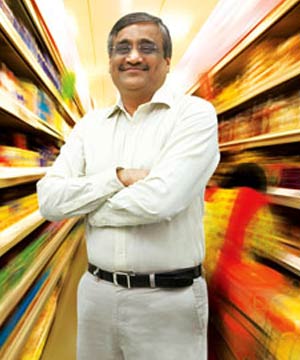

Over the last couple of days the offline retail players led by the likes of Kishore Biyani have been shouting from the rooftops about Flipkart and othe retail players indulging in predatory pricing and selling products below cost.

As a very patriotic sounding Biyani told The Economic Times “How can someone sell products below its manufacturing price? This is legally not allowed in the country. Someone can do such undercutting only to destroy competition. Just because they have foreign funding, they can’t kill local trade like that.”

He hasn’t been the only one whining against the discounts offered by the ecommerce companies like Flipkart. Praveen Khandelwal of Confederation of All India Traders (CAIT) said that the association has already approached the Ministry of Commerce. “We do not understand how online retailers gave 60-70% discounts. The prices at which they sold merchandise are lower than our purchase prices. This is a clear case of predatory pricing.”

These noises have reached the government. “We have received many inputs regarding Flipkart episode. Lot of concern have been expressed and we will look into it. Now there are many complaints. We will study the matter… Whether there is a need for a separate policy or some kind of clarification is needed, we will make it clear soon” Commerce and Industry Minister Nirmala Sitharaman said yesterday.

The first question is why should the government look into what is basically finally some healthy competition in the retail sector. Henry Hazlitt explains this beautifully in his book Economics in One Lesson. As he writes “The persistent tendency of men [is] to see only the immediate effects of a given policy, or its effects only on a special group, and to neglect to inquire what the long-run effects of that policy will be not only on that special group but on all groups.”

The offline retailers have managed to attract the attention of the government and now the government wants to look into the matter of discounts offered by ecommerce companies. Chances are that the government in the process of looking into the matter will fall victim to what Hazlitt calls the broken window fallacy.

So what exactly is the broken window fallacy? Hazlitt explains this through an example. A young hoodlum throws a stone and breaks a shop window. By the time the shopkeeper comes out, the boy has manage to disappear. A crowd starts to gather and a discussion starts. In sometime, the crowd decides rather philosophically that what happened was for the good.

As Hazlitt writes “After a while the crowd feels the need for philosophic reflection…It will make business for some glazier….After all, if windows were never broken, what would happen to the glass business?” The glazier will have more money to spend. And this will benefit other merchants. “The smashed window will go on providing money and employment in ever-widening circles. The logical conclusion from all this would be…that the little hoodlum who threw the stone, far from being a public menace, was a public benefactor,” writes Hazlitt.

On the face of it this sounds perfectly normal. But what it does not take into account is the fact that the shopkeeper will have to spend money in order to get the window repaired. And this money he could have spent on something else. In the example that Hazlitt has in his book the shopkeeper wanted to buy a suit. Now he can’t possibly buy the suit because the money has been spent on getting the window repaired.

As Hazlitt writes “The people in the crowd were thinking only of two parties to the transaction, [the shopkeeper] and the glazer. They had forgotten the potential third party involved, the tailor [who would have made the suit]. They forgot him precisely because he will not now enter the scene. They will see the new window in the next day or two. They will never see the extra suit, precisely because it will never be made. They see only what is immediately visible to the eye…It is the fallacy of overlooking secondary consequences.”

A similar thing seems to be playing out now in the battle between the ecommerce companies and the offline retailers. In the process the government, like the crowd in Hazlitt’s example, is likely to forget about the third party in the transaction i.e. the end consumer.

As I had explained in a piece yesterday, the end consumer has benefited from the discounts on offer by the ecommerce companies. While, there may have been problems with Flipkart’s recent Big Billion Day Sale, the discounts on offer on most days are genuine. And this benefits the consumers.

Ecommerce companies can offer these discounts because they do not require to maintain the massive physical infrastructure that offline retailers need to do. Over and above this, they do not need to maintain massive physical inventory and at the same time can cut through the distribution chain. These things help keep costs low, which in turn leads to discounts.

The end consumer benefits through discounts. He also now has more choice. Take the case of books. I am a big fan of crime fiction in general and Scandinavian crime fiction (translated into English) in particular. I can now buy almost all the Scandinavian crime fiction that has been translated into English from websites selling books. At the same time the choice of crime fiction available at a book store is fairly limited.

Let’s take another example shared by a friend who lives in a small town and has recently had a baby. The supply of quality diapers in his town is rather patchy. He now simply orders them online.

Further, the consumer also has more choice now when it comes to spending his money. If a consumer buys a product that costs Rs 1,000 offline at Rs 800 online, he is left with Rs 200. That money he can spend somewhere else. This will also benefit some business at the end of the day. The trouble of course is that no one knows where the consumer will end up spending the Rs 200 that he saves by buying online. Hence, a coherent argument in favour of the consumer cannot be made.

So, the likes of Biyani and his ilk may be complaining but the end consumer has benefited from the ecommerce revolution that is taking place. Another argument being offered is that ecommerce companies are taking over the business of offline retailers. As a retailer told The Hindu Business Line “The consuming class in India is in the age group of 18-30. Incidentally, they are also the ones who are driving up sales in the online space. This may erode our customer base.”

The next level of this argument will be that if this continues, then the offline retailers will have to start firing people. Hence, many people will end up losing jobs. The problem with this argument is that it again does not take the consumer into account.

Take the case of mobile phone retailers who are facing a tough time because of the discounts offered on mobile phones by ecommerce companies. The question is how many mobile phone consumers does this country have in comparison to mobile phone retailers. The number of mobile phone users is many many times the number of mobile phone retailers. So yes, mobile phone retailers are having a tough time, but the mobile phone users are benefiting (or have the potential to benefit) from the discounts being offered by the ecommerce companies and this cannot be ignored.

Further, the offline retailers have accused ecommerce companies of dumping their goods as well as predatory pricing. Sunil Jain demolishes these arguments in today’s edition of The Financial Express.

The question that Jain asks is that does Flipkart have the market power to dump goods? The entire e-retail sector in this country is selling goods worth around $4 billion, as per data from consulting firm Technopack. This is not even 1% of the $500 billion consumer market. And Flipkart is a fraction of that 1%. So, it doesn’t really have the market power to dump goods?

Further, Flipkart and other websites have been accused to selling things below cost. As Jain writes “Biyani and the others making this case will have to prove it. Just because a sale is taking place below the maximum retail price (MRP) doesn’t make it below-cost. Let’s say an article costs Rs 100 but has an MRP of Rs 200—that’s a pretty standard thing for most goods. The difference between the two is what comprises trade margins, shared between wholesalers and retailers. So as long as Flipkart is selling at over Rs 100, it is difficult to make a case for it selling below-cost—though…that is also permissible till such time that Flipkart is a dominant player.”

Also, if the selling below cost argument is taken to its logical conclusion then the “loss-leader” concept in retail chains will also have to come to an end. Investopedia defines this as a strategy “ in which a business offers a product or service at a price that is not profitable for the sake of offering another product/service at a greater profit or to attract new customers.” Airline seats being sold on a discount at the last minute will also have to stop.

It is worth remembering here that technical progress always throws people out of jobs and puts the incumbents in tough situations. Ecommerce is doing precisely that with offline retail. So does that mean there should be no ecommerce?

Hazlitt explains it best when he writes: “The technophobes, if they were logical and consistent, would have to dismiss all this progress and ingenuity as not only useless but vicious. Why should freight be carried from Chicago to New York by railroad when we could employ enormously more men, for example, to carry it all on their backs?”

PS: The irony is that Kishore Biyani who built a good part of his business by offering huge discounts over long weekends and thus created troubles for many a kirana shop, is now having problems with the same strategy.

The article originally appeared on www.FirstBiz.com on Oct 9,2014

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)