One of the pitfalls of writing on economics and finance is being regularly asked to predict how things will eventually turn out to be. Or to put it in Mumbai stock market lingo: “Kya lagta hai? (What do you feel?)”

While speaking on broad trends after one has looked through the numbers is relatively easy (like India has a real estate bubble right now) but predicting when a trend will end and how to profit from it, is very difficult (like when will the real estate bubble burst).

So, I can tell you with great confidence that prices in the real estate sector are in bubbly territory. This statement comes from the fact that the supply of real estate is way higher than its demand.

But if you were to ask me, when will prices crash and reach their lowest level, so that you can time your purchase accordingly, I wouldn’t be able to tell you that. So, in that sense my analysis is a tad useless, given that it doesn’t lead to an actionable information other than the fact that you should not be buying real estate right now. Hence, I am not in a positon to make a confident prediction about real estate or tell you exactly how I see it playing out and how you should go about profiting from it.

There is some doubt in what I write and say, and that shall always be there.

Nevertheless, despite the pitfalls, it pays to sound confident and cocksure about everything in the business of forecasting (if you don’t believe me try watching business TV for a few hours and you will know what I am exactly trying to say here).

As Dan Gardner writes in Future Babble—Why Expert Predictions Fail and Why We Believe Them Anyway: “Researchers have also shown that financial advisers who express considerable confidence in their stock forecast are more trusted than those who are less confident, even when their objective records are the same…If someone’s confidence is high, we believe they are probably right; if they are less certain, we feel they are less reliable.”

What does this mean? As Gardner writes: “This means we deem those who are dead certain the best forecasters, while those who make “probabilistic” calls…must be less accurate.” In the days of the social media and the internet this problem is even more accentuated. Not only are the so-called experts making confident predictions, so is every Jai, Vijay and Ajay.

But the thing is that just because someone is confident doesn’t mean he or she will turn out to be right. One reason is the fact that there are way too many variables at play, and keeping track of all variables and making sense of them, is not an easy task.

This is where the concept of bounded rationality comes in. As The Economist puts it: “Not only can they [human beings] not get access to all the information required, but even if they could, their minds would be unable to process it properly.” This makes making predictions a risky business.

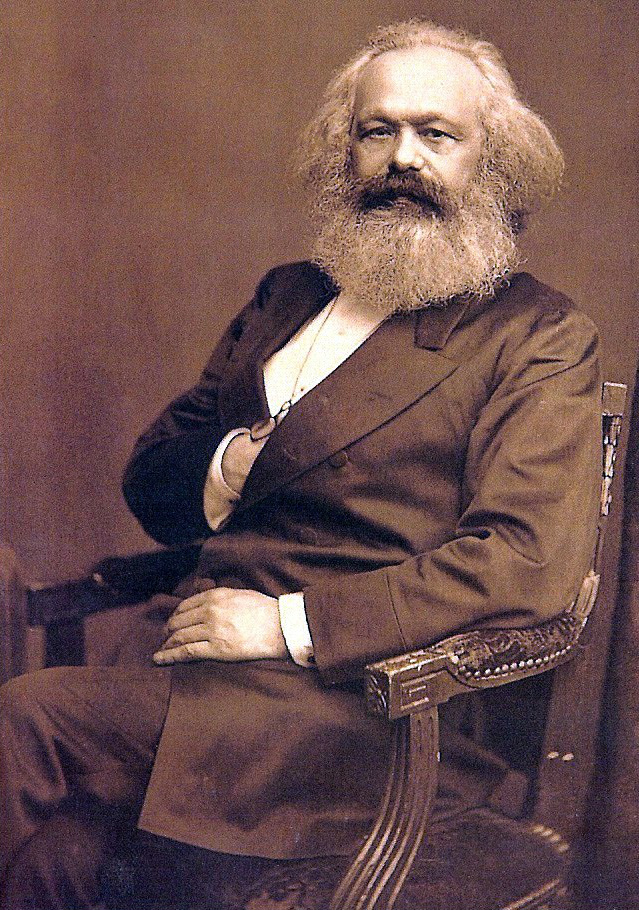

In other cases, the prediction turns out to be wrong simply because people decide to act on it. Take the case of Karl Marx. In the middle of the 19th century, working in London, Marx came up with economic insights, which have caught the imagination of every generation since then. But the thing is that Marx has turned out to be wrong.

As Yuval Noah Harari writes in Homo Deus—A Brief History of Tomorrow: “[Marx] predicted an increasingly violent conflict between the proletariat [the working class] and the capitalists, ending with the inevitable victory of the former and the collapse of the capitalist system.” In fact, Marx was certain that countries like Great Britain, United States and France, would see an industrial revolution that would spread to other parts of the world.

But Marx turned out to be wrong. Or to put it in a better way, he hasn’t turned out to be right, as yet. Does that mean his basic assertion was wrong? As Harari writes: “Marx forgot that capitalists know how to read. At first only a handful of disciples took Marx seriously and read his writing. But as these socialist firebrands gained adherents and power, the capitalists became alarmed. They too perused Das Kapital, adopting many of the tools and insights of Marxist analysts.”

And once the capitalists read what Marx had written, they started working on ensuring that what he had said does not come out to be true. As Harari writes: “Capitalists in countries such as Britain and France strove to better the lot of the workers, strengthen their national consciousness and integrate them into the political system. Consequently, when workers began voting in elections and Labour gained power in one country after another, the capitalists could still sleep soundly in their beds.”

And that is how Marx went wrong, despite being right. This is the paradox of knowledge. It is very important to understand this in the context of forecasts and predictions that have become an important part of this era that we live in.

As Harari writes: “Knowledge that does not change behaviour is useless. But knowledge that changes behaviour quickly loses its relevance. The more data we have and the better we understand history, the faster history alters its course, and the faster our knowledge becomes outdated.”

And that is something worth thinking about.

The column originally appeared in Vivek Kaul’s Diary on September 20, 2016