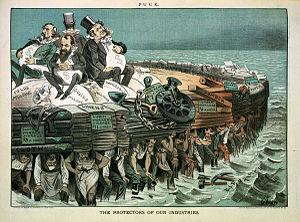

In his latest book Other People’s Money—Masters of the Universe or Servants of the People?, the British economist John Kay talks about the robber barons of the United States, who lived through the late nineteenth and the early twentieth century.

As Kay writes: “The late nineteenth century is described as ‘the gilded age’ of American capitalism. The dominant figures of that era – men such as Henry Clay Frick, Jay Gould, J.P. Morgan, John D. Rockefeller and Cornelius Vanderbilt – are often called the ‘robber barons.’”

These robber barons helped build the railroads, oil supply systems and steel mills of the United States. As Kay writes: “They were both industrialists and financers, in varying degrees…But their immense personal wealth was as much the product of financial manipulation as of productive activity.”

Now replace United States with India, and you can see the similarities. While the United States had robber barons in the nineteenth and the early twentieth century, India has had them in the twentieth and the twenty-first century.

The Reserve Bank of India governor explained the finance skills of Indian businessmen in great detail in a speech he made in November 2014. As Rajan said: “The reason so many projects are in trouble today is because they were structured up front with too little equity, sometimes borrowed by the promoter from elsewhere. And some promoters find ways to take out the equity as soon as the project gets going, so there really is no cushion when bad times hit.”

What Rajan was essentially saying here is that many Indian businessmen start a project with very little of their own money invested in it. Further, some of them even manage to tunnel out this small investment as soon as the project starts. This is typically done by over stating the cost of the project, borrowing against the higher number and then tunnelling out a portion of the debt that has been taken on to get the project going.

Also, in the last few years, many Indian businessmen have taken on more bank loans than they could have possibly repaid. They have subsequently defaulted on it or renegotiated the terms, leaving the banks in a lurch. Interestingly, even after defaulting on their loans, they have continued to be in positions of control.

As Rajan said during the course of his speech: “In much of the globe, when a large borrower defaults, he is contrite and desperate to show that the lender should continue to trust him with management of the enterprise. In India, too many large borrowers insist on their divine right to stay in control despite their unwillingness to put in new money. The firm and its many workers, as well as past bank loans, are the hostages in this game of chicken — the promoter threatens to run the enterprise into the ground unless the government, banks, and regulators make the concessions that are necessary to keep it alive.”

And if after all this, the business comes back to health, the businessmen tends to benefit the most. As Rajan said: “The promoter retains all the upside, forgetting the help he got from the government or the banks – after all, banks should be happy they got some of their money back! No wonder government ministers worry about a country where we have many sick companies but no “sick” promoters.”

These businessmen over the years have survived on essentially manipulating the system (or what we like to call jugaad) and surviving on multiple doles from the government. This is something that Rajan clearly pointed out in a recent speech, where he said: “India must resist special interest pleas for targeted stimulus, additional tax breaks and protections, directed credit, subventions and subsidies, all of which have historically rendered industry uncompetitive, government over-extended, and the country incapable of regaining its rightful position amongst nations.”

But this is easier said than done, given that India’s businessmen have always operated like this. The question is how can this change? Kay has a possible answer in his book Other People’s Money, where he suggests that the United States went from strength to strength after the links between finance and business were loosened.

As he writes: “While the ‘robber barons’ were both financers and businessmen, the leading industrialists of the first half of the twentieth century – men such as Alfred Sloan of General Motors and Harry McGowan of ICI – were primarily businessmen. Their skill was in developing the systems and cadre of professional managers needed to run a modern corporation.”

This is possible if banks go after corporates defaulting on loans with great zeal, which they currently lack. Further, a new class of capitalists needs to flourish.

The Prime Minister Narendra Modi in a recent meeting with India’s biggest businessmen asked them to increase their risk taking appetite. As the president of the Confederation of Indian Industry, a business lobby, told the media after the meeting with Modi: “Prime Minister has said that industry must take risk and increase investments…we must go out and invest.”

The trouble is India’s incumbent businessmen are not the risk taking type. As Dipankar Gupta wrote in a recent column in The Times of India: “Till the 1980s Indian businesses were shielded from foreign competition, and they returned this favour by not introducing a single innovation above street-corner jugaad…Even after liberalisation came to India in the 1990s, this risk aversion among Indian capitalists stayed firm and remained protected by a friendly state. This can best be seen in the advocacy and implementation of the current Public Private Partnership (PPP) model.”

Hence, expecting such businessmen to suddenly start taking risk is a tad absurd. That ain’t happening. So what is the way out? As I said earlier, India needs a new class of capitalists. And for that to happen, as Rajan said the other day, it is important “to improve regulation by focusing on what is absolutely necessary to create a sound business environment.”

The column originally appeared in The Daily Reckoning on Sep 22, 2015