The Economic Survey released by the ministry of finance every year before the budget is by far the best document on the ‘real’ state of the Indian economy. The latest Economic Survey released in late January, discusses the poor state of investment in India in great detail.

The investment to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio (a measure what part of the overall economy does investment form) peaked in 2007 at 35.6%. It has been falling ever since and in 2017, it had stood at 26.4%. No other country in the world has gone through such a huge investment bust, during the same period, the Survey suggests.

Further, the Survey remains pessimistic about whether India will be able to bounce back from here. For one, India’s investment slowdown is not yet over. As the Survey puts it: “Cross -country evidence indicates a notable absence of automatic bounce-backs from investment slowdowns. The deeper the slowdown, the slower and shallower the recovery.”

Evidence from other countries which have gone through a similar investment slowdown seems to suggest that a full recovery rarely happens. Further, a fall in private investment accounts for a bulk of the investment decline. This is something that can be seen from the fact that new projects announcement in the period of three months ending December 2017, came in at a 13-year low (as per data from Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy).

A fall in the investment to GDP ratio also suggests that enough jobs and employment opportunities are not be created. A recent estimate made by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy suggests that in 2017, two million jobs were created for 11.5 million Indians who joined the labour force during the year.

With sufficient jobs and employment opportunities not going around, it has impacted the earning capacity of many Indians, especially, the one million Indians entering the workforce every month.

Ultimately, enough jobs and employment opportunities not being created has translated itself into a lack of growth on the consumer demand front. This can be seen in the capacity utilisation of manufacturing firms which has varied between 70-72% for a while now. This lack of consumer demand has finally translated into falling corporate profits, over the last decade.

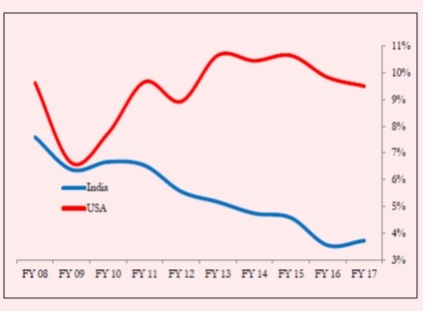

Take a look at Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Source: Economic Survey 2017-2018.

Figure 1 plots the corporate profits as a proportion of the GDP since 2008. The Indian profits are represented by the blue line, which has gone down. As the Economic Survey points out: “India’s current corporate earnings/GDP ratio has been sliding… falling to just 3½ percent.” Indian corporate profits have halved since 2008. This is a clear impact of a falling investment to GDP ratio.

Of course, no relationship in economics can be totally linear.

A falling investment rate leads to fewer jobs and employment opportunities, in turn leading to lower consumer demand and lower corporate profits.

Lower consumer demand obviously has a negative impact on the investment rate, which again has an impact on jobs, employment opportunities and corporates profits. And so the cycle works.

John Maynard Keynes, in the aftermath of the Great Depression of 1929, had suggested that when the private sector is not investing, the government needs to step in, up the ante, spend money and create consumer demand.

One of the best sectors to invest in, in order to create demand is housing. The sector has many forward and backward linkages, which can have a huge multiplier effect. As the finance minister Arun Jaitley said in his budget speech: “Under Prime Minister Awas Scheme Rural, 51 lakhs houses in year 2017-18 and 51 lakh houses during 2018-19 which is more than one crore houses will be constructed exclusively in rural areas. In urban areas the assistance has been sanctioned to construct 37 lakh houses.” A few months back, the government had announced a huge road building programme as well.

These programmes will definitely help. But the government can only do so much, given the fact that India’s investment to GDP ratio has been falling for more than a decade. The government doesn’t have access to an unlimited amount of money, and the private sector needs to start investing if the investment rate has to revive.

The private sector won’t do so, at least not immediately, because of a lack of consumer demand and also because it is just coming out of a huge borrowing binge. The government can only facilitate this situation by pushing through ease of doing business at every level.

As Jaitley said in his speech: “To carry the business reforms for ease of doing business deeper and in every State of India, the Government of India has identified 372 specific business reform actions.” These reforms need to be quickly implemented, if there has to be any hope of breaking India’s investment conundrum.

The column originally appeared in Daily News and Analysis on February 13, 2018.

Note: *T is the peak time Period *: A fifty percent recovery implies that the country attained an investment rate that reversed half of the 8.5 percentage point fall. The dots imply the percentage of the total fall that the median country namaged to reverse.

Note: *T is the peak time Period *: A fifty percent recovery implies that the country attained an investment rate that reversed half of the 8.5 percentage point fall. The dots imply the percentage of the total fall that the median country namaged to reverse.