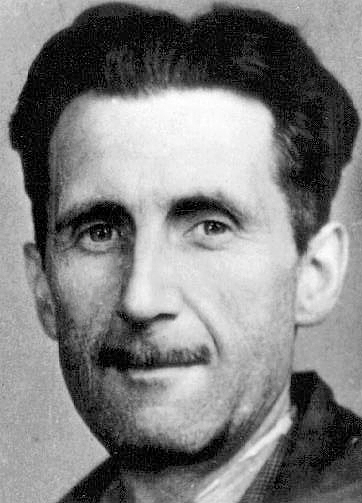

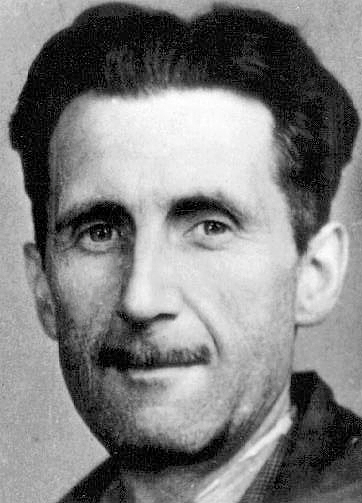

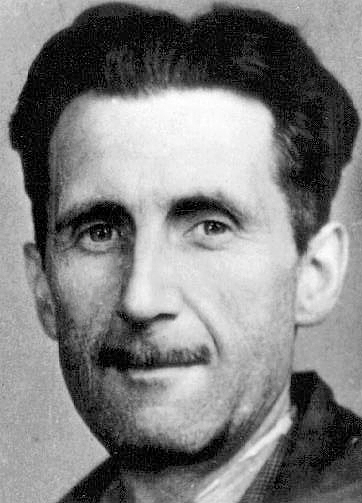

ओरवेल ने अपनी बात प्रोफेस्सर बरेलवी से काफी पहले कही थी. क्या ओरवेल की ये पंक्ति प्रोफेसर साब के शेर की प्रेरना है? अब ये तो वही बता सकते हैं.

ओरवेल ने अपनी बात प्रोफेस्सर बरेलवी से काफी पहले कही थी. क्या ओरवेल की ये पंक्ति प्रोफेसर साब के शेर की प्रेरना है? अब ये तो वही बता सकते हैं.

ओरवेल ने अपनी बात प्रोफेस्सर बरेलवी से काफी पहले कही थी. क्या ओरवेल की ये पंक्ति प्रोफेसर साब के शेर की प्रेरना है? अब ये तो वही बता सकते हैं.

There is a difference between making things simple and making them simplistic. In the zeal to make things simple a significant chunk of media’s coverage on the recently introduced Goods and Services Tax (GST) has turned out to be simplistic.

Here’s how.

There are two basic concepts at the heart of the GST. It has a self-policing feature built into it and it allows for an input tax credit. And both are linked.

Let’s start with the second feature first. What is input tax credit? Let’s say you are a manufacturer. The product you make needs different kinds of raw material. You buy this raw material from other suppliers. When you buy this raw material from other suppliers, they have already paid some indirect taxes on it and these indirect taxes are built into the price that you pay.

In the pre-GST era, you could not deduct for the taxes already paid down the value chain, while you paid your share of indirect taxes. In this way, you ended up paying a tax on tax and hence there was a cascading effect on the final price of the product.

GST subsumes many indirect taxes both at the level of the state governments as well as the central government. And that is a good thing because it actually reduces the number of taxes.

With the introduction of the GST, you can deduct the GST already paid as a part of your value chain, while paying your share of the GST. This is referred to as input tax credit.

And how do you get this input tax credit? As Section 16(2a) of the Central Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017, points out: “Notwithstanding anything contained in this section, no registered person shall be entitled to the credit of any input tax in respect of any supply of goods or services or both to him unless,–– (a) he is in possession of a tax invoice or debit note issued by a supplier registered under this Act, or such other tax paying documents as may be prescribed.”

What does this mean in simple English? It basically means that anyone claiming an input tax credit for the GST already paid down his value chain, needs to ensure that his suppliers have registered under this Act (i.e. they have a Goods and Services Tax Identification Number (GSTIN)). The individual also needs to ensure that he is in possession of an invoice from his suppliers.

This is the self-policing feature built into the GST. Anyone claiming an input tax credit needs to ensure that all his suppliers are a part of the GST as well. This basically ensures that if any supplier was operating in the informal economy, he now has to become a part of the formal economy by getting a GSTIN. Wherever this chain breaks, the government knows that somebody is not paying his fair share of taxes. So far so good.

Norman Loayza, an economist with the Development Research Group of the World Bank defines informality as “a term used to describe the collection of firms, workers, and activities that operate outside the legal and regulatory frameworks or outside the modern economy.” And given this, governments are not able to collect tax from firms operating in the informal economy. The GST is a way of ensuring that these firms become a part of the formal economy and they pay taxes.

Much of the writing in the media has focused on this and passed it as a good effect of the GST, which it is. But saying that it is only a good effect and does not have any negative sides to it, is making things simplistic instead of simple.

Let me explain.

Loayza estimates that in a typical developing country the informal economy employs 70 per cent of the labour force and produces around 35 per cent of the GDP. India has multiple estimates of the size of the informal economy.

Take a look at the following figure.

Source: Boosting Growth and Employment in the BRICS’ Prepared by ILO and VV Giri National Labour Institute, INDIA. September 15, 2016.

As per Figure 1, nearly 67 per cent of India’s labour force works in the informal economy. This touches nearly 85 per cent, if we take the informal workers in the formal economy into account as well. Many formal firms under declare the total number of people they employ.

The India Employment and Labour Report of 2014 states: “An overwhelmingly large percentage of workers (about 92 per cent) are engaged in informal employment and a large majority of them have low earnings with limited or no social protection.”

There are other estimates as well. Nevertheless, most of these estimates put the size of the labour force working in the informal economy at around 75 per cent or more of the total labour force. Also, depending on which estimate you believe the informal economy contributes 35 to 45 per cent of the GDP, which is huge.

The question is why are the firms operating in the informal economy, and not formal? The simplistic answer is that they want to avoid paying tax. And GST will make them compliant on that front.

Many Indian firms operating in the informal economy do so because going formal means following a whole host of rules and regulations, which they simply do not have the wherewithal to follow. The National Manufacturing Policy of 2011 estimates that, on an average, a manufacturing unit needs to comply with nearly 70 laws and regulations. At the same time, these units sometimes need to file as many as 100 returns a year.

Furthermore, India has 150 state level-labour laws and 44 central-level labour laws.

GST will force informal firms to go formal, the question is, will they? It really depends on whether it will be viable for them to do so. Instead of going formal, they may simply decide to shutdown. This is also a possibility, which the media seems to have taken great care not to talk about. How this will play out, no one really knows and only time will tell.

If GST has to be a real success then the ease of doing business in India needs to start improving as well. Nothing much has happened on that front.

If the informal firms shutdown, how is the situation likely to play out? Many people will end up losing jobs and this will have an impact on consumption and economic growth.

Will the smaller formal firms cash in on the situation by expanding their production and recruiting more people? Again, it’s not so easy. The average Indian manufacturing firm is very small. In many cases, it employs even less than ten people.

Many formal firms continue to want to stay small so that they don’t come under the ambit of labour laws. As Jagidsh Bhagwati and Arvind Panagariya write in India’s Tryst with Destiny: “The costs due to labour legislations rise progressively in discrete steps at seven, ten, twenty, fifty and 100 workers. As the firm size rises from six regular workers towards 100, at no point between the two thresholds is the saving in manufacturing costs sufficiently large to pay for the extra costs of satisfying these laws.” Panagariya is currently the Vice Chairman of the NITI Aayog.

The situation will end up benefitting the larger firms who will end up capturing a larger portion of the market. And this will give them pricing power as well. Of course, it will mean more taxes for the government, which can then continue with its many boondoggles or create newer ones.

Also, it is worth mentioning here that while the owners of firms working in the informal economy don’t pay taxes, those working in these firms do pay their share. Most of these workers earn lesser than Rs 2.5 lakh. Hence, they don’t come under the ambit of income tax. When they spend the money that they earn they pay indirect taxes. Also, the money they spend is income for firms operating in the formal economy, which then pay their share of income tax.

Given this, simply arguing that all informal economy is bad, is basically a very simplistic way of looking at things. Ultimately, it provides jobs to three-fourths of the labour force and that can’t be ignored. Hence, it is important that the media, economists and analysts, try to explore this other side of the GST as well.

The article originally appeared on Newslaundry on July 12, 2017.

One of the things that I have written about in the past is the fact that the Bhartiya Janata Party(BJP) led National Democratic Alliance(NDA) government is likely to continue to be in a minority in the Rajya Sabha until 2019. The next Lok Sabha elections are due in 2019.

Even if one were to be very optimistic, the NDA would touch around 100 seats in the Rajya Sabha by 2019. Why is that? Unlike the Lok Sabha, the Rajya Sabha is not elected all at once. A certain section of the members keeps retiring, elections are held for these seats and new members are elected. Hence, the composition of the Rajya Sabha keeps changing gradually unlike that of the Lok Sabha, which changes all at once.

Given that NDA does not have numbers in the Rajya Sabha, it has not been able to get key legislation passed. In a recent research report titled GST, The Way Forward, analysts Sheela Rathi and Ridham Desai of Morgan Stanley, suggest that this is about to change and by July 2016, the government may be able to push through key economic legislation like the Goods and Services Tax (GST), through the Rajya Sabha.

So what is it that Rathi and Desai are seeing which others can’t. Before we get into this, it is important to understand how the composition of the Rajya Sabha will change in the months to come. Every two years around one-third of the total members of the Rajya Sabha retire and new ones are elected.

Between March and July 2016, 75 members will retire from the Rajya Sabha. New members will be elected. These members are elected indirectly through an electoral college consisting primarily of the elected members of the state legislative assemblies. So you and me, dear readers, elect the members of legislative assemblies (MLAs) who in turn elect the members of the Rajya Sabha.

After these elections, the numbers of seats the BJP led NDA has in Rajya Sabha will go up. As Akhilesh Tilotia(the author of The Making of India), Sanjeev Prasad and Sunita Baldawa of Kotak Institutional Equities, write in a research note titled Wheels of Rajya Sabha Turn Slowly: “[In July 2016] core NDA allies will have 68 Rajya Sabha MPs (currently 61), almost similar in number to what the INC is expected to have (65)…After this round of elections in the Rajya Sabha, the next large round of elections will be in April 2018 and by then the NDA government at the Center would have completed four years of its tenure. The government will continue to have a minority position in RS until late in its term.”

So, the NDA will have 68 members in the Rajya Sabha by July 2016. While this is better than the 61 members they currently have, it is too small in a house of 245. It also needs to be mentioned here that in order to get a Constitution Amendment Bill, like the GST, passed, the approval of two-thirds of the members of both the Rajya Sabha and the Lok Sabha is needed.

A joint sitting of both the houses of Parliament cannot be called in order to get a such a Bill passed, if the houses do not agree on the Bill. Article 368 of the Indian Constitution basically mandates that both the houses pass the Bill separately with a two-thirds majority.

Currently, the Rajya Sabha has 242 members instead of the sanctioned strength of 245. A two thirds majority would mean getting the support of 163 members. So how will NDA with 68 members in the Rajya Sabha get a constitutional amendment which needs the support of 163 members passed?

Rathi and Desai make a huge leap of faith here. As they write: “Currently, BJP and its allies have 60 seats in the Upper House, and, along with parties supporting GST, there are 97 votes in favour of the bill. This count increases to 110 by the end of July with the upcoming retirements…In the first scenario, all members participate in voting. The BJP and its allies see their seat membership increase to 110 from 97 seats. There are another 44 members that are currently supporting the bill. Supporting votes add up to 154. There are another nine who are neutral at this point and could swing either way. If the government can garner support from these members, then getting to the 163 vote mark becomes likely by July 2016.”

QED.

One of the parties which Rathi and Desai list as supporting the BJP on GST is AIADMK. The party currently has 12 members in the Rajya Sabha. The Kotak analysts expects the party to continue to have 12 members even after July 2016.

Further, the AIADMK is against the GST. As AIADMK leader A. Navaneethakrishnan said in November 2015: “The GST in its present form will have a huge impact on the fiscal autonomy of States and the revenue loss it is likely to cause to Tamil Nadu will be considerable.”

Also, the party’s main leader J Jayalalitha is known to be mercurial.

Rathi and Desai also list Samajwadi Party as one of the supporters of the GST Bill. The party currently has 15 seats in the Rajya Sabha. This is expected to rise to 19 by July 2016. Samajwadi Party is the biggest party in the Rajya Sabha after Congress and the BJP.

Does the Samajwadi Party actually support GST? As Akhilesh Yadav said in early December 2015: “Without thinking much, anyone is expressing support to GST Bill in the parliament. State would be at loss.”

The analysts also assume that the Peoples Democratic Party(PDP) of Kashmir is in the NDA camp when it comes to GST. If that was the case, why haven’t the BJP and the PDP been able to form a government in Jammu and Kashmir, after the death of the chief minister and PDP leader, Mufti Mohammed Sayeed.

Also, the state finance minister Haseeb Drabu has spoken against GST in the past. As he had said in May 2015: “Jammu and Kashmir is unlikely to implement GST regime as it compromises its special position…. J&K is the only state that has the authority to legislate on all taxes and this will go with the new GST regime.”

Given this, I really don’t know how Rathi and Desai have assumed that AIADMK, PDP and SP are supporting the NDA on GST. Also, the assumption here is that the Congress party will keep sitting and not do anything about the BJP led NDA trying to get other parties in favour of GST.

Further, the Morgan Stanley analysts write: “In the second scenario, the INC (i.e., 67 current Upper House members) abstains from voting, and then the government needs 123 votes. In this situation, the bill can even pass during the second part of the budget session, between April and May. By April, we think the BJP and parties supportive of the bill will have 107 seats. in Rajya Sabha; they need another 16 seats to get the votes in the favour of the bill, which are already available to them.”

This is a politically naïve assumption which has been made to arrive at the conclusion that the NDA will get the numbers to get the GST Bill passed. Why would the Congress party give a walkover to the NDA? Beats me.

Further, the report does not take into account the state assembly elections which are due to happen in April and May 2016. The counting for four assembly elections (Assam, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Assam) and one union territory election(Puducherry) will happen on May 19.

The results of these elections will also have an impact on whether political parties will continue to support the BJP in its bid to get the GST Bill passed in the Rajya Sabha. If the BJP performs well (i.e. it wins in Assam, does well in West Bengal and manages to open its account in Kerala) the hawa will be in its favour.

If it doesn’t do well, the hawa will go against it. In this scenario, many small political parties who are in the ‘supporting’ camp may decide to desert it. Even if the BJP does well, some parties might still want to stay away, in order to portray that they are not giving in, to the BJP. This is something that cannot be known in advance.

Once these factors are taken into account it is safe to say that there are way too many holes in Morgan Stanley’s prediction of the BJP led NDA being able to get the GST Bill passed in July 2016. It’s a nice story, but on the current evidence, it doesn’t seem plausible.

The column originally appeared in the Bangalore Mirror on March 9, 2016

As I write this on the morning of September 8, 2015, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his team are meeting the top businessmen of this country along with the governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Raghuram Rajan.

The press release put out by the Prime Minister’s office pointed out that “a wide-ranging discussion is expected on the impact of recent economic events, and how best India can take advantage of them.” For a meeting which is expected to last over two hours, this is as general an agenda as it can get. Since it chooses to address everything, it will end up addressing nothing.

As far as representatives of Indian business are concerned they have constantly blamed high interest rates for investment as well as economic growth not picking up. But the point is who is responsible for high interest rates? The conventional wisdom on this matter is that the Reserve Bank of India has not been reducing the repo rate, or the rate at which it lends to banks.

Only if it was as simple as that. The repo rate is at best an indicator of which way the interest rates are headed. At the end of the day banks need to decide the interest rates they charge on their loans. A major reason that has been stopping them from lowering interest rates is the massive amount of bad loans that have been accumulated over the years.

Take the case of the State Bank of India, it has a bad loan ratio of greater than 10%, when lending to corporates. This means for every Rs 100 that the bank lends to corporates, more than Rs 10 has turned into a bad loan.

A standard explanation for these defaults is that businesses have got hit during what are bad economic times and hence, are unable to repay the loans they had taken on. While that may be true in a large number of cases, it is not totally true.

As a recent report brought out by Ernst and Young and titled Unmasking India’s NPA issues – can the banking sector overcome this phase? points out: “While corporate borrower have repeatedly blamed the economic slowdown as the primary factor behind it[i.e. defaulting on bank loans], periodic independent audits on borrowers have revealed diversion of funds or wilful default leading to stress situations.”

The question is will Modi and his team crack the whip on these defaulters and ask them to pay up? From past evidence the answer is no. If they had to, they would have already done so by now. Hence, calling the corporates for a meeting and listening to the same old things all over again, is basically a sheer of waste of time.

Further, as far Modi is concerned he has a lot of explaining to do on the economic reform front, something he had promised during the course of the election campaign last year. During the course of the last year he has come up with slogans like Make in India, Digital India etc., with very little changing on the ground.

For businesses to make in India, different things like the ease of land acquisition and electric supply, need to improve. Many state electricity boards all over the country, continue to remain in a mess. Further, the inspector raj that small businesses face, needs to be unshackled. Labour laws which stop favouring the incumbents (i.e. the labour in the organised sector) need to be brought in. Very little seems to have happened on this front.

Further, the government hasn’t been able to push through a goods and services tax either, despite making a lot of noise on that front.

The basic point is that what was Modi’s strength has now become his weakness. During the course of the election campaign last year, Modi came across as a man of action—a man who got things done. The bar was set very high with slogans like “acche din aane waale hain”.

For acche din to come Modi needs to create jobs for the 13 million Indians who are entering the workforce every year. And for that to happen he needs to unshackle many things that are holding back the economy.

The ease of doing business has to improve, if India wants to take advantage of the current economic scenario where the Chinese economy is in doldrums. Just coming up with new slogans and meeting corporates regularly won’t help on that front.

The column appeared on Firstpost on Sep 8, 2015

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)