Gross domestic product or GDP, is one of the most used or perhaps abused terms in economics. The trouble is that too many people use it without realising that it is ultimately a theoretical construct and not a real number.

In the simplest terms GDP is defined as the value of goods and services produced in a country during the course of a year. The trouble is in defining what has a value and what doesn’t. As the old GDP joke goes, when a man or a woman marries his or her housekeeper, the GDP of the country goes down. This happens simply because the housekeeper was paid for doing the house work. The spouse clearly won’t be.

On a serious note, this joke shows a big loophole in the way the GDP is calculated. The calculation takes only paid work into account. The trouble is that unpaid work forms a very important as well as large part of the economy, though this is something that most people do not realise.

As Kate Raworth writes in Doughnut Economics—Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist: “If you have never really thought of it before, then it’s time you met your inner housewife (because we all have one). She lives in the daily dealings of making breakfast, washing the dishes, tidying the house, shopping for groceries, teaching the children to walk and to share, washing clothes, caring for elderly parents, emptying the rubbish bins, collecting kids from school, helping the neighbours, making the dinner, sweeping the floor, and lending an ear.”

Most of us do these things and don’t get paid for it. Nevertheless, they are a very important part of the lives that we live.

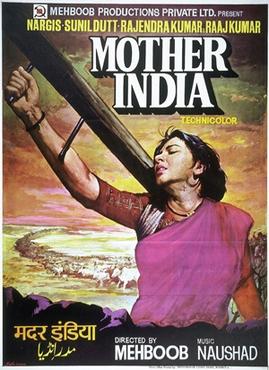

Raworth is British and hence, invocates the term inner housewife. In India, there are real housewives (not that they are not there in Britain) who just take care of the home. As per the National Sample Survey (NSS), for women in the age of 25-54, the labour force participation rate varies between 26 to 28 per cent in urban areas and 44 per cent in rural areas. Hence, most Indian women don’t work, in the conventional sense of the term. But they run their homes. Even young girls who are not married are expected to contribute towards house work.

All this never gets counted towards the GDP. As Raworth writes: “In sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia… when the state fails to deliver, and the market is out of reach, householders have to make provisions for many more of their needs directly. Millions of women and girls spend hours walking miles each day, carrying their body weight in water, food or firewood on their heads, often with a baby strapped to their back – and all for no pay.” And given that there is no pay, the work does not reflect in the GDP.

In fact, economists have even put numbers to this unpaid work. “A 2014 survey of 15,000 mothers in the USA calculated that, if women were paid the going hourly rate for each of their roles – switching between housekeeper and daycare teacher to van driver and cleaner – then stay-at-home mums would earn around $120,000 each year. Even mothers who do head out to work each day would earn an extra $70,000 on top of their actual wages.”

This unpaid work which is a very important part of a running a household smoothly as well as bringing up a child, is not reflected in the GDP. And that is a real problem. This patriarchal attitude of economics as it is practiced, needs to be corrected in the years to come.

The column originally appeared in the Bangalore Mirror on June 9, 2017.