Almost one month back prime minister Narendra Modi announced the decision to demonetise Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes. In the initial communication, the nation was told that the objective of this decision was twofold—to tackle fake currency notes as well as black money.

Somewhere down the line the communication changed and we are now being told that the objective of demonetisation is to help the country where 98 per cent of consumer transactions happen in cash, go cashless. Why did this objective suddenly change?

As on November 8, 2016, 685.80 crore Rs 1,000 notes were in circulation. Over and above this, 1716.50 crore of Rs 500 notes were in circulation. These notes were demonetised and suddenly had no value.

These demonetised notes have to be submitted with banks and post offices, by December 30, 2016. The amount will be credited into the bank

or the post office savings account. This is where things get interesting.

The hope was that many people would not deposit their black money held in the form of cash into bank accounts because it would generate an audit trail for the income tax department. In the process, black money held in the form of cash would be destroyed. Many experts suggested that black money to the extent of Rs 3,00,000 crore would be destroyed. This is what caught the attention of the people and they largely supported the decision, and to some extent still are.

But the way things are going, chances are that nothing of this sort will eventually happen. The question is why? Between November 10 and November 27, almost 53 per cent of the demonetised currency had already been deposited with banks. No new numbers have been declared since then, but media reports suggest that more than Rs 11 lakh crore has already made it back to the banking system, three weeks before the last date of depositing.

The more the money that comes back to the banks, the lesser will be the black money destroyed. The lesser is the black money destroyed, more the demonetisation plan will look like an ill-thought out decision on part of the government, which it already is to some extent.

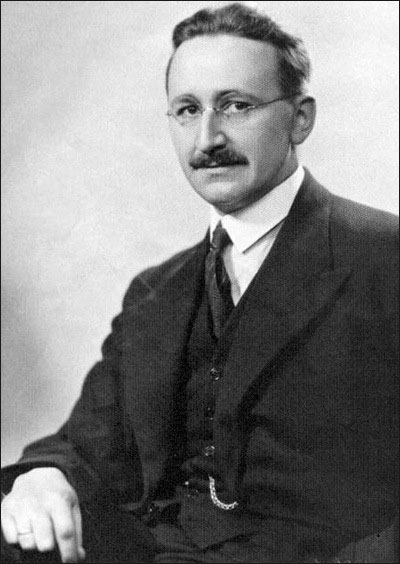

The question is what happened? The government became a victim of what the economist Friedrich Hayek has called the knowledge problem. As he wrote in a seminal article called The Use of Knowledge in Society “The economic problem of society…is a problem of the utilization of knowledge which is not given to anyone in its totality.”

This basically means that whenever the government makes a big decision like demonetisation, it thinks that it has all the knowledge required. But it never does. As Matt Ridely writes in The Evolution of Everything: “The knowledge required to organise human society is bafflingly voluminous. It cannot be held in a single human head”.

This is precisely where the government got caught out. It didn’t realise that the people will figure out various ways of turning their black money into white. This is the knowledge that Hayek talked about. Smaller merchants simply handed over their black money to their employees and asked them to deposit it, into their bank accounts. The merchants will adjust this against the salaries of their employees in the months to come.

Some black money has made it into Jan Dhan accounts. The hope here is that even if all this generates an audit trail, how many people can the Income Tax department really go after.

The bigger ones, who have black money, have been actively helped by our banking system in converting it into white. With a spate of bank managers being dismissed across banks, there is enough evidence of the same.

Still others, have been encouraged by former tax officials as well as chartered accounts, to deposit their black money into their bank accounts, show it as the income for the current year, and pay tax on it. If the income tax department has a problem with it, they can litigate. And we all know the speed at which our judicial system works.

Now only if Mr Modi had read Hayek. It would have saved all of us from so much trouble.

The column originally appeared in the Bangalore Mirror on December 7, 2016