Vivek Kaul

The petrol prices were raised by Rs 6.28 per litre yesterday. With taxes the total comes to Rs 7.54 per litre. Let’s try and understand what impact this increase in prices will have.

The primary beneficiary of this increase will be the oil marketing companies like Indian Oil, Bharat Petroleum and Hindustan Petroleum. The companies had been losing Rs 6.28 per litre of petrol they sold. Since December, when prices were last raised the companies had lost $830million in total. With the increase in prices the companies will not lose money when they sell petrol.

The increase in price will have no impact on the fiscal deficit of the government. The fiscal deficit is the difference between what the government spends and what it earns. The government does not subsidize the oil marketing companies for the losses they make on selling petrol.

It subsidizes them for losses made on selling diesel, kerosene and LPG, below cost.

The losses on account of this currently run at Rs 512 crore a day. The loss last year to these companies because of selling diesel, kerosene and LPG below cost was at Rs 138,541crore. They were compensated for this loss by the government. Out of this the government got the oil and gas producing companies like ONGC, Oil India Ltd and GAIL to pick up a tab of Rs 55,000 crore. The remaining Rs 83,000 odd crore came from the coffers of the government.

What is interesting that when the budget was presented in March, the oil subsidy bill for the year 2011-2012 (from April 1, 2011 to March 31,2012) was expected to be at around Rs 68,500 crore. The final number was Rs 14,500 crore higher.

The losses for this financial year (from April 1, 2012 to March 31,2012) are expected to be at Rs Rs. 193,880 crore. If the losses are divided between the government and the oil and gas producing companies in the same ratio as last year, then the government will have to compensate the oil marketing companies with around Rs 1,14,000 crore. The remaining money will come from the oil and gas producing companies.

The trouble is in two fronts. It will pull down the earnings of the oil and gas producing companies. But that’s the smaller problem. The bigger problem is it will push up the fiscal deficit. If we look at the assumptions made in the budget for the current financial year, the oil subsidies have been assumed at Rs Rs 43,580 crore. If the government has to compensate the oil marketing companies to the extent of Rs 1,14,000 crore, it means that the fiscal deficit will be pushed up by around Rs 70,000 crore more (Rs 1,14,000crore minus Rs 43,580 crore), assuming all other expenses remain the same.

A higher fiscal deficit would mean that the government would have to borrow more. A higher government borrowing will ‘crowd-out’ the private borrowing and push interest rates higher. This would mean higher equated monthly installments(EMIs) for people who have loans to pay off or are even thinking of borrowing.

The only way of bringing down the interest rates is to bring down the fiscal deficit. The fiscal deficit target for the financial year 2012-2013 has been set at Rs 5,13,590 crore. The government raises this money from the financial system by issuing bonds which pay interest and mature at various points of time. Of this amount that the government will raise, it will spend Rs 3,19,759 crore to pay interest on the debt that it already has. Rs 1,24,302 crore will be spent to payback the debt that was raised in the previous years and matures during the course of the year 2012-2013. Hence a total of Rs 4,44,061 crore or a whopping 86.5% of the fiscal deficit will be spent in paying interest on and paying off previously issued debt. This is an expenditure that cannot be done away with.

The other major expenditure for the government during the course of the year are subsidies. The total cost of subsidies during the course of this year has been estimated to be at Rs Rs 1,90,015 crore. The subsidies are basically of three kinds: oil, food and petroleum. The food subsidy is at Rs 75,000 crore. This is a favourite with Sonia Gandhi and hence cannot be lowered. And more than that there is a humanitarian angle to it as well.

The fertizlier subsidies have been estimated at Rs 60,974 crore. This is a political hot potato and any attempts to cut this in the pst have been unsuccessful and have had to be rolled back. There are other subsidies amounting to Rs 10,461 crore which are minuscule in comparison to the numbers we are talking about.

This leaves us with oil subsidies which have been estimated to be at Rs 43,580 crore. This as we see will be overshot by a huge level, if oil prices continue to be current levels. Even if prices fall a little, the subsidy will not come down by much. .

Hence if the government has to even maintain its deficit (forget bringing it down) the only way out currently is to increase the price of diesel, LPG and kerosene. Diesel is a transport fuel and an increase in its price will push prices inflation in the short term. But maintain the fiscal deficit will at least keep interest rates at their current levels and not push them up from their already high levels.

If the government continues to subsidize diesel, LPG and kerosene, interest rates are bound to go up because it will have to borrow more. This will mean higher EMIs for sure. It would also mean businesses postponing expansion because higher interest rates would mean that projects may not be financially viable. It would also mean people borrowing lesser to buy homes, cars and other things, leading to a further slowdown in a lot of sectors. In turn it would mean lower economic growth.

That’s the choice the government has to make. Does it want the citizens of this country to pay higher fuel and gas prices? Or does it want them to pay higher EMIs? There is no way of providing both.

(The article originally appeared at www.rediff.com on May 24,2012. http://www.rediff.com/business/slide-show/slide-show-1-special-higher-oil-prices-or-higher-emis-take-your-pick/20120524.htm)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Fiscal Deficit

Petrol bomb is a dud: If only Dr Singh had listened…

Vivek Kaul

The Congress led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government finally acted hoping to halt the fall of the falling rupee, by raising petrol prices by Rs 6.28 per litre, before taxes. Let us try and understand what will be the implications of this move.

Some relief for oil companies:

The oil companies like Indian Oil Company (IOC), Bharat Petroleum (BP) and Hindustan Petroleum(HP) had been selling oil at a loss of Rs 6.28 per litre since the last hike in December. That loss will now be eliminated with this increase in prices. The oil companies have lost $830million on selling petrol at below its cost since the prices were last hiked in December last year. If the increase in price stays and is not withdrawn the oil companies will not face any further losses on selling petrol, unless the price of oil goes up and the increase is not passed on to the consumers.

No impact on fiscal deficit:

The government compensates the oil marketing companies like Indian Oil, BP and HP, for selling diesel, LPG gas and kerosene at a loss. Petrol losses are not reimbursed by the government. Hence the move will have no impact on the projected fiscal deficit of Rs 5,13,590 crore. The losses on selling diesel, LPG and kerosene at below cost are much higher at Rs 512 crore a day. For this the companies are compensated for by the government. The companies had lost Rs 138,541 crore during the last financial year i.e.2011-2012 (Between April 1,2011 and March 31,2012).

Of this the government had borne around Rs 83,000 crore and the remaining Rs 55,000 crore came from government owned oil and gas producing companies like ONGC, Oil India Ltd and GAIL.

When the finance minister Pranab Mukherjee presented the budget in March, the oil subsidies for the year 2011-2012 had been expected to be at Rs Rs 68,481 crore. The final bill has turned out to be at around Rs 83,000 crore, this after the oil producing companies owned by the government, were forced to pick up around 40% of the bill.

For the current year the expected losses of the oil companies on selling kerosene, LPG and diesel at below cost is expected to be around Rs 190,000 crore. In the budget, the oil subsidy for the year 2012-2013, has been assumed to be at Rs 43,580 crore. If the government picks up 60% of this bill like it did in the last financial year, it works out to around Rs 114,000 crore. This is around Rs 70,000 crore more than the oil subsidy that the government has budgeted for.

Interest rates will continue to remain high

The difference between what the government earns and what it spends is referred to as the fiscal deficit. The government finances this difference by borrowing. As stated above, the fiscal deficit for the year 2012-2013 is expected to be at Rs 5,13,590 crore. This, when we assume Rs 43,580crore as oil subsidy. But the way things currently are, the government might end up paying Rs 70,000 crore more for oil subsidy, unless the oil prices crash. The amount of Rs 70,000 crore will have to be borrowed from financial markets. This extra borrowing will “crowd-out” the private borrowers in the market even further leading to higher interest rates. At the retail level, this means two things. One EMIs will keep going up. And two, with interest rates being high, investors will prefer to invest in fixed income instruments like fixed deposits, corporate bonds and fixed maturity plans from mutual funds. This in other terms will mean that the money will stay away from the stock market.

The trade deficit

One dollar is worth around Rs 56 now, the reason being that India imports more than it exports. When the difference between exports and imports is negative, the situation is referred to as a trade deficit. This trade deficit is largely on two accounts. We import 80% of our oil requirements and at the same time we have a great fascination for gold. During the last financial year India imported $150billion worth of oil and $60billion worth of gold. This meant that India ran up a huge trade deficit of $185billion during the course of the last financial year. The trend has continued in this financial year. The imports for the month of April 2012 were at $37.9billion, nearly 54.7% more than the exports which stood at $24.5billion.

These imports have to be paid for in dollars. When payments are to be made importers buy dollars and sell rupees. When this happens, the foreign exchange market has an excess supply of rupees and a short fall of dollars. This leads to the rupee losing value against the dollar. In case our exports matched our imports, then exporters who brought in dollars would be converting them into rupees, and thus there would be a balance in the market. Importers would be buying dollars and selling rupees. And exporters would be selling dollars and buying rupees. But that isn’t happening in a balanced way.

What has also not helped is the fact that foreign institutional investors(FIIs) have been selling out of the stock as well as the bond market. Since April 1, the FIIs have sold around $758 million worth of stocks and bonds. When the FIIs repatriate this money they sell rupees and buy dollars, this puts further pressure on the rupee. The impact from this is marginal because $758 million over a period of more than 50 days is not a huge amount.

When it comes to foreign investors, a falling rupee feeds on itself. Lets us try and understand this through an example. When the dollar was worth Rs 50, a foreign investor wanting to repatriate Rs 50 crore would have got $10million. If he wants to repatriate the same amount now he would get only $8.33million. So the fear of the rupee falling further gets foreign investors to sell out, which in turn pushes the rupee down even further.

What could have helped is dollars coming into India through the foreign direct investment route, where multinational companies bring money into India to establish businesses here. But for that the government will have to open up sectors like retail, print media and insurance (from the current 26% cap) more. That hasn’t happened and the way the government is operating currently, it is unlikely to happen.

The Reserve Bank of India does intervene at times to stem the fall of the rupee. This it does by selling dollars and buying rupee to ensure that there is adequate supply of dollars in the market and the excess supply of rupee is sucked out. But the RBI does not have an unlimited supply of dollars and hence cannot keep intervening indefinitely.

What about the trade deficit?

The trade deficit might come down a little if the increase in price of petrol leads to people consuming less petrol. This in turn would mean lesser import of oil and hence a slightly lower trade deficit. A lower trade deficit would mean lesser pressure on the rupee. But the fact of the matter is that even if the consumption of petrol comes down, its overall impact on the import of oil would not be that much. For the trade deficit to come down the government has to increase prices of kerosene, LPG and diesel. That would have a major impact on the oil imports and thus would push down the demand for the dollar. It would also mean a lower fiscal deficit, which in turn will lead to lower interest rates. Lower interest rates might lead to businesses looking to expand and people borrowing and spending that money, leading to a better economic growth rate. It might also motivate Multi National Companies (MNCs) to increase their investments in India, bringing in more dollars and thus lightening the pressure on the rupee. In the short run an increase in the prices of diesel particularly will lead higher inflation because transportation costs will increase.

Freeing the price

The government had last increased the price of petrol in December before this. For nearly five months it did not do anything and now has gone ahead and increased the price by Rs 6.28 per litre, which after taxes works out to around Rs 7.54 per litre. It need not be said that such a stupendous increase at one go makes it very difficult for the consumers to handle. If a normal market (like it is with vegetables where prices change everyday) was allowed to operate, the price of oil would have risen gradually from December to May and the consumers would have adjusted their consumption of petrol at the same pace. By raising the price suddenly the last person on the mind of the government is the aam aadmi, a term which the UPAwallahs do not stop using time and again.

The other option of course is to continue subsidize diesel, LPG and kerosene. As a known stock bull said on television show a couple of months back, even Saudi Arabia doesn’t sell kerosene at the price at which we do. And that is why a lot of kerosene gets smuggled into neighbouring countries and is used to adulterate diesel and petrol.

If the subsidies continue it is likely that the consumption of the various oil products will not fall. And that in turn would mean oil imports would remain at their current level, meaning that the trade deficit will continue to remain high. It will also mean a higher fiscal deficit and hence high interest rates. The economic growth will remain stagnant, keeping foreign businesses looking to invest in India away.

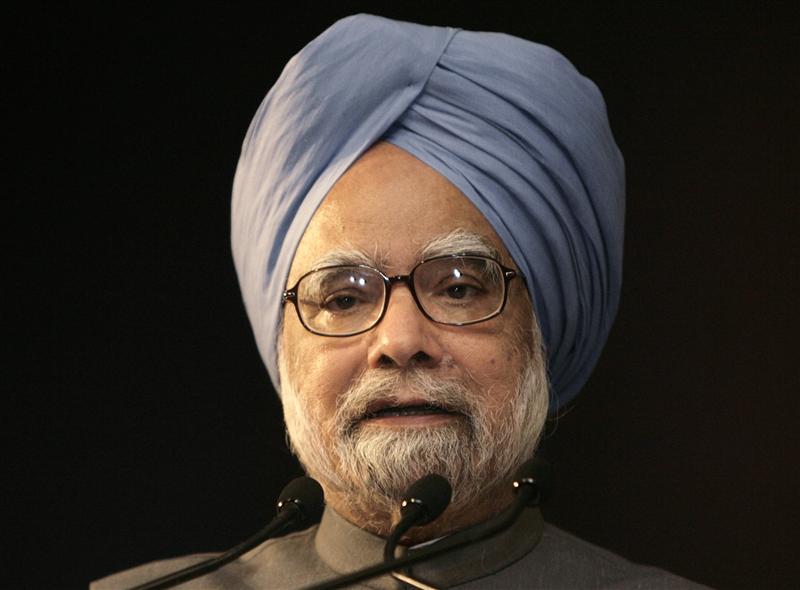

Manmohan Singh as the finance minister started India’s reform process. On July 24, 1991, he backed his “then” revolutionary proposals of opening up India’s economy by paraphrasing Victor Hugo: “No power on Earth can stop an idea whose time has come.”

Good economics is also good politics. That is an idea whose time has come. Now only if Mr Singh were listening. Or should we say be allowed to listen..

(The article originally appeared at www.firstpost.com on May 24,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/petrol-bomb-is-a-dud-if-only-dr-singh-had-listened-319594.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

It’s not Greece: Cong policies responsible for rupee crash

Vivek Kaul

All is well in India under the rule of the “Gandhi” family. That’s what the Finance Minister Pranab Mukjerjee has been telling us. And the rupee’s fall against the dollar is primarily because of problems in Greece. And Spain. And Europe. And other parts of the world. As I write this one dollar is worth around Rs 55 (actually Rs 54.965 to be precise, but we can ignore a few decimal points). The rupee has fallen around 22% in value against the dollar in the last one year.

The larger view among analysts and experts who track the foreign exchange market is that a dollar will soon be worth Rs 60. And by then there might be problems in some other part of the world and the rupee’s fall might be blamed on the problems there. As a late professor of mine used to say, with a wry smile on his face “Since we are all born on this mother earth, there is some sort of symbiosis between us.”

So let’s try and understand why the underlying logic to the rupee’s fall against the dollar is not as simple as it is made out to be.

Dollar is the safe haven

As economic problems have come to the fore in Europe (As I have highlighted in If PIIGS have to fly they will have to exit the Euro http://www.firstpost.com/world/if-piigs-have-to-fly-they-will-need-to-exit-the-euro-314589.html) the large institutional investors have moved out of the Euro into the dollar. A year back one dollar was worth €0.71, now it’s worth €0.78. So the dollar has gained against the Euro, no doubt.

But the argument being made is that this is global trend and that dollar has gained in value against lot of other major currencies. Is that true? A year back one dollar was worth 0.88 Swiss Francs, now it is worth 0.93 Swiss Francs. So it has gained in value against the Swiss currency.

What about the British pound? A year back the dollar was worth £0.62, now it’s worth £0.63. Hence the dollar has barely moved against the pound. A dollar was worth around 82 Japanese yen around a year back. Now it’s worth around 79.5yen. It has lost value against the Japanese yen. The dollar has gained in value against the Brazilian Real. It was worth around 1.63real a year back. It is now worth over 2 real. So yes, the dollar has gained in value against the other currencies but not against all currencies.

What is ironic is that the world at large is considering dollar to be a safe haven and moving money into it, by buying bonds issued by the American government. The debt of the US government is now around $14.6trillion, which is almost equal to the US gross domestic product of $15trillion. But since everyone considers it to be a safe haven it has become a safe haven.

But let’s get back to the point at hand. So, not all currencies have lost value against the dollar and those that have lost value, have lost it in varying degrees. This tells us that there are other individual issues at play as well when it comes to currencies losing value against the dollar.

What is happening in India?

The Indian government has been spending much more money than it has been earning over the last few years. In other words the fiscal deficit of the government has been on its way up. For the financial year 2007-2008 (i.e. the period between April 1,2007 and March 31, 2008) the fiscal deficit stood at Rs 1,26,912 crore. This shot up to Rs 5,21,980 crore for the financial year 2011-2012. In a time frame of five years the fiscal deficit has shot up by nearly 312%. During the same period the income earned by the government has gone up by only 36% to Rs 7,96,740 crore. The fiscal deficit targeted for the current financial year 2012-2013(i.e. between April 1, 2012 and March 31,2013) is a little lower at Rs 5,13,590 crore. The huge increase in fiscal deficit has primarily happened because of the subsidy on food, fertilizer and petroleum.

The tendency to overshoot

Also it is highly likely that the government might overshoot its fiscal deficit target like it did last year. In his budget speech last year Pranab Mukherjee had set the fiscal deficit target for the financial year 2011-2012, at 4.6% of GDP. He missed his target by a huge margin when the real number came in at 5.9% of GDP. The major reason for this was the fact that Mukherjee had underestimated the level of subsidies that the government would have to bear. He had estimated the subsidies at Rs 1,43,750 crore but they ended up costing the government 50.5% more at Rs 2,16,297 crore.

Generally all the three subsidies of food, fertilizer and petroleum are underestimated, but the estimates on the oil subsidies are way off the mark. For the year 2011-2012, oil subsidies were assumed to be at Rs 23,640crore. They came in at Rs 68,481 crore. This has been the case in the past as well. In 2010-2011 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2010 and March 31, 2011) he had estimated the oil subsidies to be at Rs 3108 crore. They finally came in 20 times higher at Rs 62,301 crore. Same was the case in the year 2009-2010 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2009 and March 31, 2010). The estimate was Rs 3109 crore. The real bill came in nearly eight times higher at Rs 25,257 crore (direct subsidies + oil bonds issued to the oil companies).

The increasing fiscal deficit

The fiscal deficit has gone up over the years primarily because an increase in expenditure has not been matched with an increase in revenue. Revenue for the government means various forms of taxes and other forms of revenue like selling stakes in public sector enterprises.

The fact of the matter is that Indians do not like to pay income tax or any other kind of tax. This a throw back from the days of the high income tax rate in the 60s, 70s and the 80s, when a series of Finance Ministers (from C D Deshmukh to Yashwantrao Chavan and bureaucrats like Manmohan Singh) implemented high income tax rates in the hope that taxing the “rich” would solve all of India’s problems.

In the early 1970s the highest marginal rate of tax was 97%. The story goes that JRD Tata sold some property every year to pay taxes (income tax plus wealth tax) which worked out to be more than his yearly income. Of course everybody was not like the great JRD, and because of the high tax rates implemented by various Congress governments over the years, a major part of the Indian economy became black. Dealings were carried out in cash. Transactions were made but they were never recorded, because if they were recorded tax would have to be paid on them.

A series of exemptions were granted to corporate India as well, and companies like Reliance Industries did not pay any income tax for years. As a result of this India and Indians did not and do not like paying tax.

Various lobbies have also emerged which have ensured that those that they represent are not taxed. As Professor Amartya Sen wrote in a column in The Hindu earlier this year “It is worth asking why there is hardly any media discussion about other revenue-involving problems, such as the exemption of diamond and gold from customs duty, which, according to the Ministry of Finance, involves a loss of a much larger amount of revenue (Rs.50,000 crore per year)”.

As he further points out “The total “revenue forgone” under different headings, presented in the Ministry document, an annual publication, is placed at the staggering figure of Rs.511,000 crore per year. This is, of course, a big overestimation of revenue that can be actually obtained (or saved), since many of the revenues allegedly forgone would be difficult to capture — and so I am not accepting that rosy evaluation.”

But even with the overestimation the fact of the matter is that a lot of tax that can be collected from those who can pay is not being collected, and that of course means a higher fiscal deficit.

The twin deficit hypothesis

The hypothesis basically states that as the fiscal deficit of the country goes up its trade deficit (i.e. the difference between its exports and imports) also goes up. Hence when a government of a country spends more than what it earns, the country also ends up importing more than exporting.

But why is that? The fiscal deficit goes up because the increase in expenditure is not matched by an increase in taxes. This leaves people with a greater amount of money in their hands. Some portion of this money is used towards buying goods and services, which might be imported from abroad. This leads to greater imports and thus a higher trade deficit. The situation in India is similar. The government of India has been spending more than it has been earning without matching the increase in income with higher taxes, which in turn has led to increasing incomes and that to some extent has been responsible for an increase in Indian imports. But that could have hardly been responsible for the trade deficit of $185billion that India ran in 2011-2012. The imports for the month of April 2012 were at $37.9billion, nearly 54.7% more than the exports which stood at $24.5billion. So the trend has continued even in this financial year.

The golden oil shock

India exports a major part of its oil needs. On top of that it is obsessed with gold. Last year we imported 1000 tonnes of it. Very little of both these commodities priced in dollars is dug up in India. So we have to import them.

This pushes up our imports and makes them greater than our exports. These imports have to be paid for in dollar. When payments are to be made importers buy dollars and sell rupees. When this happens, the foreign exchange market has an excess supply of rupees and a short fall of dollars. This leads to rupee losing value against the dollar. In case our exports matched our imports, then exporters who brought in dollars would be converting them into rupees, and thus there would be a balance in the market. Importers would be buying dollars and selling rupees. And exporters would be selling dollars and buying rupees. But that isn’t happening in a balanced way.

This to some extent explains the current rupee dollar rate of $1 = Rs 55. The Reserve Bank of India does intervene at times to stem the fall of the rupee. This it does by selling dollars and buying rupee. But the RBI does not have an unlimited supply of dollars and hence cannot keep intervening indefinitely.

As mentioned earlier the major part of the trade deficit is because of the fact that we need to import oil. Oil prices have been high for the last few years, though recently they have fallen. Oil is sold in dollars. Hence when India needs to buy oil it needs to pay in dollars. But with the rupee constantly losing value against the dollar, it means that Indian companies have to more per barrel of oil in rupees.

The government of India does not pass on a major part of the increase in the price of oil to the end consumer and hence subsidizes the prices of diesel, LPG, kerosene etc. This means that the oil companies have to sell these products at a loss to the consumer. The government in turn compensates these companies for the loss. This leads to the expenditure of the government going up and hence it incurs a higher fiscal deficit.

No passing the buck

If the government had not subsidized prices of oil products and passed them onto the end consumer, their consumption would have come down. With prices of oil products not rising as much as they should people have not adjusted their consumption accordingly. An increase in price typically leads to a fall in demand. If the increased price of oil had been passed onto the end consumer, the demand for oil would have come down. This would have meant that a fewer number of dollars would have been required to pay for the oil being imported, in turn leading to a lower trade deficit and hence lesser pressure on the rupee-dollar rate.

So let me summarise the argument I am making. The higher fiscal deficit in the form of subsidies has pushed up the trade deficit which in turn has led to rupee losing value against the dollar. The solution is to get consumers to pay the “right” price. With this the fiscal deficit can be brought down to some extent. If these products are priced correctly, their consumption is likely to come down as well in the near future, given that their prices will go up. Lower consumption is likely to lead to lower imports and thus a lower trade deficit. A lower trade deficit would also mean that the fall of the rupee against the dollar may stop. This in turn would mean a lower price for the oil we import in rupee terms and that in turn help overall economic growth. A lower fiscal deficit will lead to lower government borrowing and hence lesser “crowding out” and so lower interest rates, which might get corporates and individuals interested in borrowing again.

The long term solution

What has been suggested above is a short term solution, which given the way the Congress led UPA government operates is unlikely to be implemented. The main problem is that while it’s quite a noble idea to provide subsidies in the form of food, fertilizer, kerosene etc to the India’s poor, it has to be matched with an increase in taxes. An increase in income taxes rates isn’t going to help much because only a minuscule portion of India pays income tax (basically the salaried class).

What is needed is to get larger number of people to pay tax to pay for all the subsidies that are doled out. This can be done by simplifying the income tax act. This was tried when the government tried to come up with the Direct Taxes Code(DTC), which was very simple and straightforward and had done away with most exemptions. In its original form the DTC was a pleasure to read. But of course if it had been implemented scores of people who do not pay income tax would have to pay income tax. In its current form the DTC is another version of Income Tax Act.

Another way is to target specific communities of people who do not pay income tax even though they earn a huge amount of money, but all in “black”. For starters the targeting property dealers that line up almost every street in Delhi might be a good idea. Once, people see that the government is serious about collecting taxes, they are more likely to pay up than not. And there is no better way than starting with the capital.

(The article originally appeared at www.firstpost.com on May 23,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/dont-blame-greece-cong-policies-responsible-for-rupees-crash-318280.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and he can be reached at [email protected])

Why rupee is on a freefall …

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

“Free Fallin!” is an old American country song sung by Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. The rupee surely is now on a free “heartbreaking” fall. The last that I looked at the numbers, the dollar was worth around Rs 54.7, the lowest level ever for it has ever reached against the dollar. It is well on its way to touching Rs 55 against the dollar. Some analysts have even predicted that it will soon touch Rs 60 against the dollar.

So what is making the rupee fall? There are several interlinked reasons for the same. Let me offer a few here.

Trade deficit

India ran a trade deficit of nearly $185billion in the financial year 2011-2012 (i.e. between April 1, 2011 and March 31,2012). Trade deficit refers to a situation where a country imports more than it exports. So in the last financial year India’s import of goods and services was $185billion more than its exports.

This trend has continued in the current financial year as well. The Indian imports for the month of April 2012 were at $37.9billion, almost 55% more than its exports at $24.5bilion.

Imports have to be paid for in dollars because that is the international currency that everybody accepts. They cannot be paid for in rupees. Now when payments have to be made in dollars, the importers sell rupees and buy dollars. When this happens the foreign exchange market suddenly has an excess supply of rupees and a short fall of dollars. This leads to rupee losing value against the dollar. This is the basic reason why rupee has been losing value against the dollar because we have been importing much more than we have been exporting. In case our exports matched our imports, then exporters who brought in dollars would be converting them into rupees, and thus there would be a balance in the market. Importers would be buying dollars and selling rupees. And exporters would be selling dollars and buying rupees. But that isn’t happening in a balanced way.

The RBI intervention

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) tries to stem the fall of the rupee at times. It does this by selling dollars and buying rupees to ensure that there is an adequate supply of dollars in the market and at the same time any excess supply of rupees is sucked out. This is done in order to ensure that the rupee either maintains or gains value against the dollar. But the RBI cannot do this indefinitely for the simple reason that it has a limited amount of dollars. The RBI can print rupees and create them out of thin air, but it cannot do the same with the dollar.

But that still doesn’t answer the basic question of why does India import more than it exports.

Why does India run a trade deficit?

India runs a trade deficit on two accounts. One is that it has to import oil to meet a major portion of its domestic needs. And the second is the fact that Indians have a huge fascination for gold. Last year India imported around 1000 tonnes of gold. So we do not produce enough of the oil that we use and the gold that we buy. This in turn means that we have to import this from abroad. Both oil and gold are internationally sold in dollars. The price of both oil and gold has been going up for a while (though very recently it has been falling). This means more and more dollars have to be paid for importing them. This, as explained above, leads to a glut of rupees and an increased demand for the dollars, thus pushing down the value of the rupee against the dollar.

On April 1, 2011, one dollar was worth Rs 44.44. Between then and March 31, 2012, India ran a trade deficit of $185billion. And it has continued that in the month of April 2012 as well. This has led to one dollar being currently worth Rs 54.7.

Subsidies

What has also happened is that the government of India has not allowed the oil companies to pass on the increased cost of oil to the end consumer. Hence products like kerosene, diesel and LPG continued to be subsidized. The government in turn pays the oil companies for the losses leading to an increased fiscal deficit. But more than that with prices not rising as much as they should people have not adjusted their consumption accordingly. An increase in price typically leads to a fall in demand. If the increased price of oil had been passed onto the end consumer, the demand for oil would have come down. This would have meant that a fewer number of dollars would have been required to pay for the oil being imported, in turn leading to a lower trade deficit and hence lesser pressure on the rupee-dollar rate.

To conclude

When imports are more than exports what it means is that the country is paying more dollars for the imports than it is earning from the exports. This difference obviously comes from the foreign exchange reserves that India has accumulated over the years. But that clearly isn’t healthy given our imports are more than 50% of our exports and there is a limited supply of foreign exchange reserves.

So the market is now worried about this and is further pushing down the value of the rupee. The only way to control the fall of the rupee for the government is show the market that it serious about cutting down the trade deficit. And this can only be done by pricing the various oil products like diesel and kerosene, correctly. This in turn will lead to a lower demand for these products and help bring down the trade deficit. It will also push down the fiscal deficit, given that the subsidy burden of the government will be eliminated or come down. On the flip side an increase in the price of oil products will lead to increased inflation, at least in the short term.

In the end the only way to stem the fall of the rupee against the dollar is to eliminate and if not that, at least bring down, oil subsidy. Will that happen? Will the allies of the Congress led United Progressive Alliance government allow that to happen?

I remain pessimistic.

(This post originally appeared on Rediff.com on May 18,2012. http://www.rediff.com/business/slide-show/slide-show-1-column-why-the-rupee-is-on-a-freefall/20120518.htm)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Yesterday, once more! Is the world economy going the Japan way?

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

High risk means high returns.

Or does it?

Not always.

When more risk does not mean more return

The ten year bond issued by the United States (US) government currently gives a return of around 1.8% per year. Bonds are financial securities issued by governments to finance their fiscal deficits i.e. the difference between what they earn and what they spend.

Returns on similar bonds issued by the government of United Kingdom (UK) are at1.9% per year.

Nearly five years back in July 2007 before the start of the financial crisis the return on the US bonds was at 5.1% per year. The return on British bonds was at 5.5% per year.

The return on German bonds back then was around 4.6% per year. Now it stands at 1.44% per year.

Since the start of the financial crisis governments all over the world have been running huge fiscal deficits in order to try and create some economic growth. They have been financing these deficits through increasing borrowing.

In 2007, the deficit of the US government stood at $160billon. This difference was met through borrowing. The accumulated debt of the US government at that point of time was $5.035trillion.

In 2012, the deficit of the US government is expected to be at $1.327trillion or around 8.3times more than the deficit in 2007. The accumulated debt of the US government is also around three times more now and has crossed $14trillion.

The situation in the United Kingdom is similar. In 2007 the fiscal deficit was at £9.7billion. The projected deficit for 2012 is around 9.3times more at £90billion. The government debt as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) has gone up from around 37% of GDP to around 67% of GDP.

The same trend seems to be happening throughout the countries of Western Europe as well. Hence we can conclude that it is more risky to lend to the governments of United States, United Kingdom and countries like Germany and France in Western Europe. Though to give Germany the due credit it doesn’t run fiscal deficits as large as US or UK for that matter. Its fiscal deficit in 2010 had stood at €100billion but was cut to around €25.8billion in 2011.

Even though the riskiness of lending to these countries has gone up, the investors have been demanding lower returns from the governments of these countries. Why is that?

The answer might very well lie in what happened in Japan in the late 1980s.

The Japan story

The Japanese central bank started running a low interest policy to help exports from the mid 1980s. This other than helping exports fuelled massive bubbles in both the stock market as well as the real estate market. The Nikkei 225, Japan’s premier stock market index, returned 237% from the start of 1985 to December 29,1989, the day it peaked at a level of 38,916 points. The real estate prices also shot through the roof. As Paul Krugman points out in The Return of Depression Economics “Land, never cheap in crowded Japan, had become incredibly expensive…the land underneath the square mile of Tokyo’s Imperial Palace was worth more than the entire state of California.”

This was the mother of all bubbles.

Yasushi Mieno took over as the 26th governor of the Bank of Japan, the Japanese central bank, on December 17, 1989. Eight days later on December 25, 1989, he shocked the market by raising the interest rate. And more than that, he publicly declared that he wanted the land prices to fall by 20%, which he later upped to 30%. Mieno didn’t stop and kept raising interest rates.

The stock market crashed. And by October 1990 it was down nearly 40%. Since then the stock market has largely been on its way down. And it currently quotes at 8,900 points down 77% from the peak.

The real estate prices also fell but not at the same fast rate as the stock market. As Ruchir Sharma writes in Breakout Nations – In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracle “ “The greatest bubble in human history” burst in 1990 with no pain at all, like falling off Everest without breaking a bone. At its peak Japan accounted for 40 percent of the property value of the planet, but instead of collapsing, the price of real estate slowly declined at a 7% annual rate for two decades, ultimately falling by a total of about 80%. There was never a major round of foreclosures or bankruptcies, as the government kept bailing out debtors, ruining its own finances.”

The GDP growth rate collapsed from 3.32% in 1991 to -0.14% in 1999. In the next ten years i.e. between 2000 and 2009, the GDP growth rate never went beyond 2.74% and was at -5.37% in 2009.

The balance sheet depression

Japan has been in what economist Richard Koo calls a balance sheet recession. What this means in simple English is that after bubbles burst, specially real estate bubbles, the private sector companies as well as individuals and families who had speculated on the bubble end up with a lot of excessive debt and an asset (like land or stocks) which is losing value. The excessive debt has to repaid. Given this individuals and companies try to save, in order to repay the debt. But what is good for the individual is not always good for the overall economy.

The paradox of thrift

John Maynard Keynes unarguably the greatest economist of the twentieth century called this the paradox of thrift. What Keynes said was that when it comes to thrift or saving, the economics of an individual differs from the economics of the system as a whole.

If one person saves more then saving makes tremendous sense for him. But as more and more people start doing the same thing there is a problem. This is primarily because what is expenditure for one person is an income for someone else. Hence, when everybody spends less, businesses see a fall in revenue. This means lower aggregate demand and hence slower or even no growth for the overall economy.

The Japanese savings rate at the time when the bubble popped was around 0%. After this the Japanese started to save more and the savings rate of the Japanese private sector and households increased. It reached around 16% of the GDP in the year 2000.

All this money was being used to pay off the excess debt that had been accumulated. This meant slower growth for Japan. The government in turn tried to pump economic growth by spending more and more money. For this it took on more debt and now the Japanese government debt to GDP ratio is around 240%.

Ironically as the government debt went up the return on the government debt kept coming down. As Martin Wolf of Financial Times points out in a recent column “At the end of 1990, when its “bubble economy” went pop, the Japanese government’s 10-year bond was yielding 6.7 per cent…But yields on 10-year Japanese government bonds (JGBs) fell to close to 2 per cent in 1997 and then, with sizeable fluctuations, to troughs of 0.8 per cent in 1998, 0.4 per cent in 2003 and, recently, to 0.9 per cent. In short, the worse the Japanese government’s present and prospective debt position has become, the lower the interest rates on JGBs has also become.” (All returns per year)

The reason for this in retrospect is very straightforward. As the Japanese individuals and companies were saving more they did not want to risk their savings in either the stock market which had been continuously falling or the real estate market which was also falling, though at a slower rate. Hence a major part of the savings went into JGBs which they thought were safer. Given that there was great demand for JGBs the Japanese government could get away with offering lower returns on its bonds, even though over the years they became riskier.

The Japan Way

Richard Koo believes that what happened in Japan over the last twenty years is now happening in the US, UK and parts of Europe. Individuals in these countries are saving more to pay off their excess debts. An average American in the month of March 2012 saved 3.8% of his disposable income in March 2012. Before the crisis the American savings rate had become negative. . The same stands true for Great Britain where savings of household were -3% at the time the crisis struck. They have since gone up to 3% of GDP. The corporate sector was saving 3% of GDP is now saving 5% of GDP. Same stands true for Spain, Ireland and Portugal where savings were in negative territory (i.e. the people were borrowing and spending) before the crisis struck, and are now going up. In the case of Ireland the savings have gone up from -10% of GDP to around 5% of the GDP since the crisis struck.

Hence companies and individuals across countries are saving more to pay off the excess debt they had accumulated. This in turn has meant that they are spending lesser money than they used to. This has led to slower economic growth. A large part of these savings is going into government bonds keeping returns low. Retail investors have taken out nearly $260billion out of equity mutual funds in the United States since 2008, even though the stock market has doubled in the last three years. At the same time they have invested nearly $800billion in bond funds, which give very low returns.

ZIRP – Zero interest rate policy

The governments of these countries have cut interest rates to almost 0% levels and are also borrowing and spending more money. That as was the case in Japan has resulted in some economic growth, but nowhere as much as they had expected. Even though governments want their citizens and companies to borrow and spend money in order to revive economic growth, they are in no mood to do that.

The citizens would rather pay off their existing debt than take on new debt. And the companies need to feel that the economic opportunity is good enough to invest, which it clearly isn’t. That explains to a large level why US companies are sitting on more than $2trillion of cash.

The banks are also not willing to take on the risk of lending at such low interest rates, as was the case in Japan. What has also not helped is the case of continuously bailing out the financial sector like was the case in Japan. Hence real estate prices in countries like Spain still need to fall by 35% to come back at normal levels.

Slow growth

All in all most of the Western world is headed towards the Japan way, which means slow economic growth in the years to come. As Sharma writes “Over the next decade, growth in the United States, Europe and Japan is likely to slow…owing to the large debt overhang”. This will impact exports out of countries like China, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, India etc. The Chinese exports for the month of April 2012 grew at 4.9% in comparison to 8.9% during the same period last year. This in turn has pushed down imports. Imports grew at a negligible 0.33% against the expected 11%.

A slowdown in Chinese imports immediately means lower prices for commodities. As Sharma puts it “It’s my conviction that the China-commodity connection will fall apart soon. China has been devouring raw materials at a rate way out of line with the size of its economy… Since 1990, China’s share of global demand for commodities ranging from aluminum to zinc has skyrockected from the low single digits to 40,50,60 % – even though China accounts for only 10% of total global output.” .

Over a longer term slower growth in the Western World will also means slower and lower stock markets. As the old Chinese curse goes “may you live in interesting times”. The interesting times are upon us.

(This post originally appeared on Firstpost.com on May 17,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/japan-disease-is-spreading-high-risk-and-low-returns-311952.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])