The minister of finance, Arun Jaitley, did not make any changes in the tax slabs in the budget for 2016-2017 which was presented yesterday.

The basic exemption limit continued to be at Rs 2.5 lakh and other tax slabs also continued to remain the same. This is typically one section of the budget which excites the salaried middle class. But Jaitley had nothing to offer on this front.

Interestingly, when Jaitley was in the opposition he had demanded that the income tax ceiling be increased to Rs 5 lakh, from the Rs 2 lakh level that had prevailed, at that point of time. As he had said in April 2014 “Direct Tax should be reduced. If the Income-Tax limit is raised from Rs 2 lakh to Rs 5 lakh, 3 crore people will save Rs 24 crore which will lead to a small impact of 1 to 1.5 percent of National Tax Fund.”

On February 29, 2016, Jaitley presented his third budget as the finance minister. Nevertheless, even now the income tax limit is at Rs 2.5 lakh, half of the Rs 5 lakh limit that Jaitley had demanded when he was in opposition.

The question is why? The simple answer is—politicians in opposition behave very differently from those in power. But there is a better answer than this.

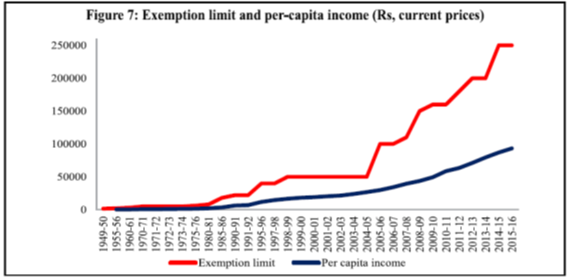

Take a look at the following chart reproduced from the Economic Survey for 2015-2016, which was released on February 26, 2016.

What does this tell us? It shows us very clearly that the income tax exemption limit has risen at a much faster rate in India than the per capita income.

As the Economic Survey points out: “We can calculate in some sense the “missing taxpayers” in India—not those who are evading taxes altogether or under-reporting taxes but those who have legitimately gone under the tax radar due to “generous” government policy.”

And who are these missing taxpayers? These are those taxpayers who got left out because the income tax threshold has been raised from the level of Rs 1.5 lakh in 2008-2009. As the Economic Survey points out: “If the threshold had been maintained at Rs. 1,50,000 (the threshold limit in 2008-2009)….we find that there would have been an additional 1.65 crore units incorporated within the taxation system (In 2012-2013 and an addition of about 39.5 percent) and tax revenues would have been about Rs 31,500 crores greater.” The tax to GDP ratio of the country would have gone up by 0.32% if the income tax exemption limit had not been raised.

The amount now, will be more than Rs 31,500 crore. And this is quite a lot of money for a government which is likely to see its expenses go up in 2016-2017, after the recommendations of the seventh pay commission increasing the salaries of central government employees and pensions of retired central government employees, are accepted.

What this also tells us is that Jaitley’s calculation of increasing the exemption limit to Rs 5 lakh, costing only Rs 24 crore, was basically wrong. When the tax-exemption limit went from Rs 1.5 lakh in 2008-2009 to Rs 2 lakh in 2012-2013, it cost the government Rs 31,500 crore. Increasing the limit to Rs 5 lakh would cost considerably more.

In fact, there is a lesson or two India can learn from China on this front, the Economic Survey points out: “Chinese success in bringing more citizens into the individual income tax net owes to setting a reasonable threshold for paying taxes and not changing it unduly. In contrast, in India, exemption thresholds for income taxes have been consistently raised.”

This has led to a situation where as many Indians are not paying income tax, as could have, if the exemption limit had not been raised at a much greater rate than the per-capita income.

Of course, Jaitley did not know all this when he was in the opposition. But now he is in the government and has access to the best possible economic brains in the country, as well as data, on which he can base his decisions on. Clearly his demand to increase the income tax exemption limit to Rs 5 lakh, when he was in the opposition, was just based on a whim and not any numbers.

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

The column originally appeared on Huff Post India on March 2, 2016