Have you ever heard someone call equity a short term investment class? Chances are no. “I have always had this notion for many years that people buy equities because they like to be excited. It’s not just about the returns they make out of it… You can build a case for equities on a three year basis. But long term investing is all rubbish, I have never believed in it,” says Shankar Sharma, vice-chairman & joint managing director, First Global. In this freewheeling

interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul.

Six months into the year, what’s your take on equities now?

Globally markets are looking terrible, particularly emerging markets. Just about every major country you can think of is stalling in terms of growth. And I don’t see how that can ever come back to the go-go years of 2003-2007. The excesses are going to take an incredible amount of time to work their way out. They are not even prepared to work off the excesses, so that’s the other problem.

Why do you say that?

If you look at the pattern in the European elections the incumbents lost because they were trying to push for austerity. And the more leftist parties have come to power. Now leftists are usually the more austere end of the political spectrum. But they have been voted to power, paradoxically, because they are promising less austerity. All the major nations in the world are democracies barring China. And that’s the whole problem. You can’t push through austerity that easily in a democracy, but that is what is really needed. Even China cannot push through austerity because of a powder-keg social situation. And I find it very strange when people criticise India for subsidies and all that. India is far less profligate than many nations including China.

Can you elaborate on that?

Every country has to subsidise, be it farm subsidies in the West or manufacturing subsidies in China, because ultimately whether you are a capitalist or a communist, people are people. They don’t necessarily change their views depending on which political ideology is at the centre. They ultimately want freebies and handouts. In a country like India, they don’t even want handouts they just want subsistence, given the level of poverty. The only thing that you can do with subsidies is to figure out how to control them. But a lot of it is really out of your control. If you have a global inflation in food prices or oil prices you are not increasing the quantum in volume terms of the subsidy. But because of price inflation, the number inflates. So why blame India? I find it absurd that the Financial Times or the Economist are perennially anti-India. They just isolate India and say that it has got wasteful expenditure programmes. A lot of countries hide things. India, unfortunately, is far more transparent in its reporting. It is easy to pick holes when you are transparent. China gives no transparency so people assume that whatever is inside the black box must be okay. That said, I firmly believe the UID program, when fully implemented, will make subsidies go lower by cutting out bogus recipients.

If increased austerity is not a solution, where does that leave us?

Increased austerity, while that is a solution, it is not achievable. If that is not possible what is the solution? You then have a continual stream of increasing debt in one form or the other, keep calling it a variety of names. But you just keep kicking the can down the road for somebody else to deal with it as long as the voter is happy. Given this, I don’t see how you can have any resurgence. Risk appetite is what drives equity markets. Otherwise you and I would be buying bonds all the time. In today’s environment and in the foreseeable future, we are overfed with risk. Where is the appetite to take more risk and go, buy equities?

So are you suggesting that people won’t be buying stocks?

Well you can get pretty good returns in fixed income. Instead of buying emerging-market stocks if you buy bonds of good companies, you can get 6-7% dollar yield, and if you leverage yourself two times or something, you are talking about annual returns of 14-15% dollar returns. You can’t beat that by buying equities, boss! Even if you did beat that by buying equities, let’s say you made 20%, it is not a predictable 20%, which has been my case for a long time against equities. Equities are a western fashion. I have always had this notion for many years that people buy equities because they like to be excited. It’s not just about the returns they make out of it: it is about the whole entertainment quotient attached to stock investing that drives investors. There is 24-hour television. Tickers. Cocktail discussions. Compared with that, bonds are so boring and uncool. Purely financially, shorn of all hype, equities have never been able to build a case for themselves on a ten-year return basis. You can build a case for equities on a three-year basis. But long-term investing is all rubbish, I have never believed in it.

So investing regularly in equities, doing SIPs, buying Ulips, doesn’t make sense?

I don’t buy the whole logic of long-term equity investing because equity investing comes with a huge volatility attached to it. People just say “equities have beaten bonds”. But even in India they have not. Also people never adjust for the volatility of equity returns. So if you make 15% in equity and let’s say, in a country like India, you make 10% in bonds – that’s about what you might have averaged over a 15-20 year period because in the 1990s we had far higher interest rates. Interest rates have now climbed back to that kind of level of 9-10%. Divide that by the standard deviation of the returns and you will never find a good case for equities over a long-term period. So equity is actually a short-term instrument. Anybody who tells you otherwise is really bluffing you. All the fancy graphs and charts are rubbish.

Are they?

Yes. They are all massaged with sort of selective use of data to present a certain picture because it’s a huge industry which feeds off it globally. So you have brokers like us. You have investment bankers. You have distributors. We all feed off this. Ultimately we are a burden on the investor, and a greater burden on society — which is also why I believe that the best days of financial services is behind us: the market simply won’t pay such high costs for such little value added. Whatever little return that the little guy gets is taken away by guys like us. How is the investor ever going to make money, adjusted for volatility, adjusted for the huge cost imposed on him to access the equity markets? It just doesn’t add up. The customer never owns a yacht. And separately, I firmly believe making money in the markets is largely a game of luck. Even the best investors, including Buffet, have a strike rate of no more than 50-60% right calls. Would you entrust your life to a surgeon with that sort of success rate?! You’d be nuts to do that. So why should we revere gurus who do just about as well as a coin-flipper. Which is why I am always mystified why so many fund managers are so arrogant. We mistake luck for competence all the time. Making money requires plain luck. But hanging onto that money is where you require skill. So the way I look at it is that I was lucky that I got 25 good years in this equity investing game thanks to Alan Greenspan who came in the eighties and pumped up the whole global appetite for risk. Those days are gone. I doubt if you are going to see a broad bull market emerging in equities for a while to come.

And this is true for both the developing and the developed world?

If anything it is truer for the developing world because as it is, emerging market investors are more risk-averse than the developed-world investors. We see too much of risk in our day to day lives and so we want security when it comes to our financial investing. Investing in equity is a mindset. That when I am secure, I have got good visibility of my future, be it employment or business or taxes, when all those things are set, then I say okay, now I can take some risk in life. But look across emerging markets, look at Brazil’s history, look at Russia’s history, look at India’s history, look at China’s history, do you think citizens of any of these countries can say I have had a great time for years now? That life has been nice and peaceful? I have a good house with a good job with two kids playing in the lawn with a picket fence? Sorry, boss, that has never happened.

And the developed world is different?

It’s exactly the opposite in the west. Rightly or wrongly, they have been given a lifestyle which was not sustainable, as we now know. But for the period it sustained, it kind of bred a certain amount of risk-taking because life was very secure. The economy was doing well. You had two cars in the garage. You had two cute little kids playing in the lawn. Good community life. Lots of eating places. You were bred to believe that life is going to be good so hence hey, take some risk with your capital.

The government also encouraged risk taking?

The government and Wall Street are in bed in the US. People were forced to invest in equities under the pretext that equities will beat bonds. They did for a while. Nevertheless, if you go back thirty years to 1982, when the last bull market in stocks started in the United States and look at returns since then, bonds have beaten equities. But who does all this math? And Americans are naturally more gullible to hype. But now western investors and individuals are now going to think like us. Last ten years have been bad for them and the next ten years look even worse. Their appetite for risk has further diminished because their picket fences, their houses all got mortgaged. Now they know that it was not an American dream, it was an American nightmare.

At the beginning of the year you said that the stock market in India will do really well…

At the beginning of the year our view was that this would be a breakaway year for India versus the emerging market pack. In terms of nominal returns India is up 13%. Brazil is down 3%. China is down, Russia is also down. The 13% return would not be that notable if everything was up 15% and we were up 25%. But right now, we are in a bear market and in that context, a 13-15% outperformance cannot be scoffed off at.

What about the rupee? Your thesis was that it will appreciate…

Let me explain why I made that argument. We were very bearish on China at the beginning of the year. Obviously when you are bearish on China, you have to be bearish on commodities. When you are bearish on commodities then Russia and Brazil also suffer. In fact, it is my view that Russia, China, Brazil are secular shorts, and so are industrial commodities: we can put multi-year shorts on them. So that’s the easy part of the analysis. The other part is that those weaknesses help India because we are consumers of commodities at the margin. The only fly in the ointment was the rupee. I still maintain that by the end of the year you are going to see a vastly stronger rupee. I believe it will be Rs 44-45 against the dollar. Or if you are going to say that is too optimistic may be Rs 47-48. But I don’t think it’s going to be Rs 60-65 or anything like that. At the beginning of the year our view that oil prices will be sharply lower. That time we were trading at around $105-110 per barrel. Our view was that this year we would see oil prices of around $65-75. So we almost got to $77 per barrel (Nymex). We have bounced back a bit. But that’s okay. Our view still remains that you will see oil prices being vastly lower this year and next year as well, which is again great news for India. Gold imports, which form a large part of the current account deficit, shorn of it, we have a current account deficit of around 1.5% of the GDP or maybe 1%. We imported around $60 billion or so of gold last year. Our call was that people would not be buying as much gold this year as they did last year. And so far the data suggests that gold imports are down sharply.

So there is less appetite for gold?

Yes. In rupee terms the price of gold has actually gone up. So there is far less appetite for gold. I was in Dubai recently which is a big gold trading centre. It has been an absolute massacre there with Indians not buying as much gold as they did last year. Oil and gold being major constituents of the current account deficit our argument was that both of those numbers are going to be better this year than last year. Based on these facts, a 55/$ exchange rate against the dollar is not sustainable in my view. The underlyings have changed. I don’t think the current situation can sustain and the rupee has to strengthen. And strengthen to Rs 44, 45 or 46, somewhere in that continuum, during the course of the year. Imagine what that does to the equity market. That has a big, big effect because then foreign investors sitting in the sidelines start to play catch-up.

Does the fiscal deficit worry you?

It is not the deficit that matters, but the resultant debt that is taken on to finance the deficit. India’s debt to GDP ratio has been superb over the last 8-9 years. Yes, we have got persistent deficits throughout but our debt to GDP ratio was 90-95% in 2003, that’s down to maybe 65% now. So explain that to me? The point is that as long as the deficit fuels growth, that growth fuels tax collections, those tax collections go and give you better revenues, the virtuous cycle of a deficit should result in a better debt to GDP situation. India’s deficit has actually contributed to the lowering of the debt burden on the national exchequer. The interest payments were 50% of the budgetary receipts 7-8 years back. Now they are about 32-33%. So you have basically freed up 17% of the inflows and this the government has diverted to social schemes. And these social schemes end up producing good revenues for a lot of Indian companies. The growth for fast-moving consumer goods, mobile telephony, two wheelers and even Maruti cars, largely comes from semi-urban, semi-rural or even rural India.

What are you trying to suggest?

This growth is coming from social schemes being run by the government. These schemes have pushed more money in the hands of people. They go out and consume more. Because remember that they are marginal people and there is a lot of pent-up desire to consume. So when they get money they don’t actually save it, they consume it. That has driven the bottomlines of all FMCG and rural serving companies. And, interestingly, rural serving companies are high-tax paying companies. Bajaj Auto, Hindustan Lever or ITC pay near-full taxes, if not full taxes. This is a great thing because you are pushing money into the hands of the rural consumer. The rural consumer consumes from companies which are full taxpayers. That boosts government revenues. So if you boost consumption it boosts your overall fiscal situation. It’s a wonderful virtuous cycle — I cannot criticise it at all. What has happened in past two years is not representative. It is only because of the higher oil prices and food prices that the fiscal deficit has gone up.

What is your take on interest rates?

I have been very critical of the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) policies in the last two years or so. We were running at 8-8.5% economic growth last year. Growth, particularly in the last two or three years, has been worth its weight in gold. In a global economic boom, an economic growth of 8%, 7% or 9% doesn’t really matter. But when the world is slowing down, in fact growth in large parts of the world has turned negative, to kill that growth by raising the interest rate is inhuman. It is almost like a sin. And they killed it under the very lofty ideal that we will tame inflation by killing growth. But if you have got a matriculation degree, you will understand that India’s inflation has got nothing to do with RBI’s policies. Your inflation is largely international commodity price driven. Your local interest rate policies have got nothing to do with that. We have seen that inflation has remained stubbornly high no matter what Mint Street has done. You should have understood this one commonsensical thing. In fact, growth is the only antidote to inflation in a country like India. When you have economic growth, average salaries and wages, kind of lead that. So if your nominal growth is 15%, you will 10-20% salary and wage hikes – we have seen that in the growth years in India. Then you have more purchasing power left in the hands of the consumer to deal with increased price of dal or milk or chicken or whatever it is. If the wage hikes don’t happen, you are leaving less purchasing power in the hands of people. And wage hikes won’t happen if you have killed economic growth. I would look at it in a completely different way. The RBI has to be pro-growth because they no control of inflation.

So they basically need to cut the repo rate?

They have to.

But will that have an impact? Because ultimately the government is the major borrower in the market right now…

Look, again, this is something that I said last year — that it is very easy to kill growth but to bring it back again is a superhuman task because life is only about momentum. The laws of physics say that you have to put in a lot of effort to get a stalled car going, yaar. But if it was going at a moderate pace, to accelerate is not a big issue. We have killed that whole momentum. And remember that 5-6%, economic growth, in my view, is a disastrous situation for a country like India. You can’t say we are still growing. 8% was good. 9% was great. But 4-5% is almost stalling speed for an economy of our kind. So in my view the car is at a standstill. Now you need to be very aggressive on a variety of fronts be it government policy or monetary policy.

What about the government borrowings?

The government’s job has been made easy by the RBI by slowing down credit growth. There are not many competing borrowers from the same pool of money that the government borrows from. So far, indications are that the government will be able to get what it wants without disturbing the overall borrowing environment substantially. Overall bond yields in India will go sharply lower given the slowdown in credit growth. So in a strange sort of way the government’s ability to borrow has been enhanced by the RBI’s policy of killing growth. I always say that India is a land of Gods. We have 33 crore Gods and Goddesses. They find a way to solve our problems.

So how long is it likely to take for the interest rates to come down?

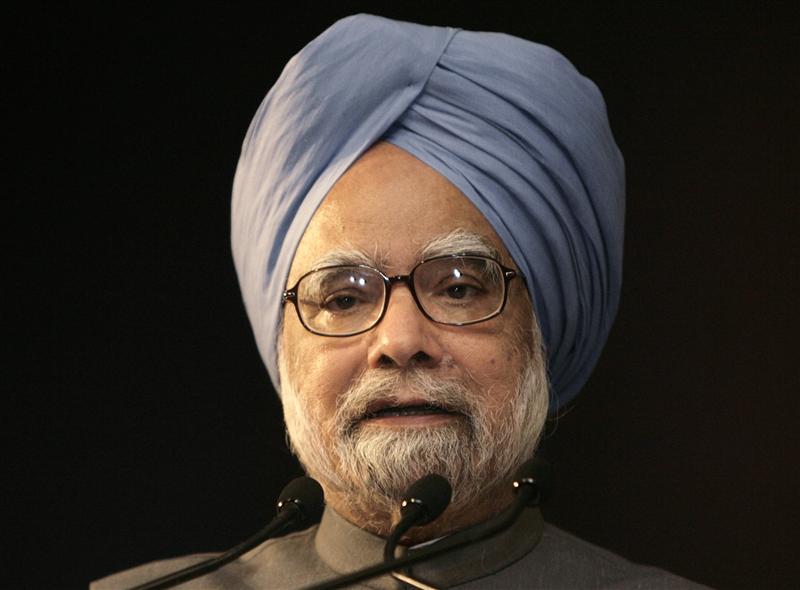

The interest rate cycle has peaked out. I don’t think we are going to see any hikes for a long time to come. And we should see aggressive cuts in the repo rate this year. Another 150 basis points, I would not rule out. Manmohan Singh might have just put in the ears of Subbarao that it’s about time that you woke up and smelt the coffee. You have no control over inflation. But you have control over growth, at least peripherally. At least do what you can do, instead of chasing after what you can’t do.

Manmohan Singh in his role as a finance minister is being advised by C Rangarajan, Montek Singh Ahulwalia and Kaushik Basu. How do you see that going?

I find that economists don’t do basic maths or basic financial analysis of macro data. Again, to give you the example of the fiscal deficit and I am no economist. All I kept hearing was fiscal deficit, fiscal deficit, fiscal deficit. I asked my economist: screw this number and show me how the debt situation in India has panned out. And when I saw that number, I said: what are people talking about? If your debt to GDP is down by a third, why are people focused on the intermediate number? But none of these economists I ever heard them say that India’s debt to GDP ratio is down. I wrote to all of them, please, for God’s sake, start talking about it. Then I heard Kaushik Basu talk about it. If a fool like me can figure this out, you are doing this macro stuff 24×7. You should have had this as a headline all the time. But did you ever hear of this? Hence I am not really impressed who come from abroad and try to advise us. But be that as it may it is better to have them than an IAS officer doing it. I will take this.

You talked about equity being a short-term investment class. So which stocks should an Indian investor be betting his money right now?

I am optimistic about India within the context of a very troubled global situation. And I do believe that it’s not just about equity markets but as a nation we are destined for greatness. You can shut down the equity markets and India would still be doing what it is supposed to do. But coming from you I find it a little strange…

I have always believed that equity markets are good for intermediaries like us. And I am not cribbing. It’s been good to me. But I have to be honest. I have made a lot of money in this business doesn’t mean all investors have made a lot of money. At least we can be honest about it. But that said, I am optimistic about Indian equities this year. We will do well in a very, very tough year. At the beginning of the year, I thought we will go to an all-time high. I still see the market going up 10-15% from the current levels.

So basically you see the Sensex at around 19,000?

At the beginning of the year, you would have taken it when the Sensex was at 15,000 levels. Again, we have to adjust our sights downwards. A drought angle has come up which I think is a very troublesome situation. And that’s very recent. In light of that I do think we will still do okay, it will definitely not be at the new high situation.

What stocks are you bullish on?

We had been bearish on infrastructure for a very long time, from the top of the market in 2007 till the bottom in December last year. We changed our view in December and January on stocks like L&T, Jaiprakash Industries and IVRCL. Even though the businesses are not, by and large, of good quality — I am not a big believer in buying quality businesses. I don’t believe that any business can remain a quality business for a very long period of time. Everything has a shelf life. Every business looks quality at a given point of time and then people come and arbitrage away the returns. So there are no permanent themes. And we continue to like these stocks. We have liked PSU banks a lot this year, because we see bond yields falling sharply this year.

Aren’t bad loans a huge concern with these banks?

There is a company in Delhi — I won’t name it. This company has been through 3-4 four corporate debt restructurings. It is going to return the loans in the next year or two. If this company can pay back, there is no problem of NPAs, boss. The loans are not bogus loans without any asset backing. There are a lot of assets. At the end of every large project there is something called real estate. All those projects were set up with Rs 5 lakh per acre kind of pricing for land. Prices are now Rs 50 lakh per acre or Rs 1 crore or Rs 1.5 crore per acre. If nothing else, dismantle the damn plant, you will get enough money from the real estate to repay the loans of the public sector banks. So I am not at all concerned on the debt part. If the promoter finds that is going to happen, he will find some money to pay the bank and keep the real estate.

On the same note, do you see Vijay Mallya surviving?

100% he will survive. And Kingfisher must survive, because you can’t only have crap airlines like Jet and British Airways. If God ever wanted to fly on earth, he would have flown Kingfisher.

So he will find the money?

Of course! At worst, if United Spirits gets sold, that’s a stock that can double or triple from here. I am very optimistic about United Spirits. Be it the business or just on the technical factor that if Mallya is unable to repay and his stake is put up for sale, you will find bidders from all over the world converging.

So you are talking about the stock and not Mallya?

Haan to Mallya will find a way to survive. Indian promoters are great survivors. We as a nation are great survivors.

How do you see gold?

I don’t have a strong view on gold. I don’t understand it well enough to make big call on gold, even though I am an Indian. One thing I do know is that our fascination with gold has very strong economic moorings. We should credit Indians for having figured out what is a multi century asset class. Indians have figured out that equities are a fashionable thing meant for the Nariman Points of the world, but for us what has worked for the last 2000 years is what is going to work for the next 2000 years.

What about the paper money system, how do you see that?

I don’t think anything very drastic where the paper money system goes out of the window and we find some other ways to do business with each. Or at least I don’t think it will happen in my life time. But it’s a nice cute notion to keep dreaming about.

At least all the gold bugs keep talking about the collapse of the paper money system…

I know. I don’t think it’s going to happen. But I don’t think that needs to happen for gold to remain fashionable. I don’t think the two things are necessarily correlated. I think just the notion of that happening is good enough to keep gold prices high.

(A slightly smaller version of the interview appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on July 31,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/money/interview_you-can-shut-the-equity-market-india-would-still-be-doing-fine_1721939)

(Interviewer Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Dollar

An interview with the mysterious, reclusive, FoFoA….

Half way through the interview, I ask him where does he see the price of gold reaching in the days to come. “Well, I don’t see gold’s trajectory being typical of what you’d expect to see in a bull market….And I expect that physical gold will be repriced somewhere around $55,000 per ounce in today’s purchasing power. I have to add that purchasing power part because it will likely be concurrent with currency devaluation,” he replies. Meet FOFOA, an anonymous blogger whose writings on fofoa.blogspot.com have taken the world by storm over the last few years. In a rare interview he talks to Vivek Kaul on paper money, the fall of the dollar, the coming hyperinflation and the rise of “physical” gold.

The world is printing a lot paper money to solve the economic problems. But that doesn’t seem to be happening. What are your views on that?

Paper money being printed to solve the problems… this was *always* on the cards. It doesn’t surprise me, nor does it anger me, because I understand that it was always to be expected. The monetary and financial system we’ve been living with—immersed in like fish in water—for the past 90 years uses the obligations of counterparties as its foundation. These obligations are noted on paper. In describing the specific obligations these papers represent, we use well-known words like dollars, euro, yen, rupees and yuan. But what do these purely symbolic words really mean? What are these paper obligations really worth in the physical world? Ultimately, after 90 years, we have arrived at our inevitable destination: the intractable problem of an unimaginably intertwined, interconnected Gordian knot of purely symbolic obligations. A Gordian knot is like an unsolvable puzzle. It cannot be untangled. The only solution comes from “thinking outside the box.” You’ve got to cut the knot to untangle it. So the endgame was always going to be debasing these purely symbolic units. Anyone who expected anything else simply fooled themselves into believing the rules wouldn’t be changed.

Do you see the paper money continuing in the days to come?

Yes, of course! Paper money, or today’s equivalent which is electronic currency, is the most efficient primary medium of exchange ever used in all of human history. To see this you only need to abandon the idea of accumulating these symbolic units for your future financial security. They aren’t meant for that! They are great for trading in the here-and-now, not for storing for the unknown future. To paraphrase Silvio Gesell, an economist in favor of symbolic currency almost a century ago, “All the physical assets of the world are at the disposal of those who wish to save, so why should they make their savings in the form of money? Money was not made to be saved!” In hindsight, this statement is true whether money is a hard commodity like gold or silver, or a symbolic word like dollar, euro or rupee. In both cases, saving in “money” leads to monetary tension between the debtors and the savers. When money was a hard commodity, this tension was sometimes even released through bloodshed, like the French Revolution. So no, I don’t think we’re swinging back to a hard currency this time.

Do you see the world going back to the gold standard?

No, of course not! “The gold standard” means different things depending on which period you are talking about. But in all cases it used gold to denominate credit, the economy’s primary medium of exchange. Today we have a really efficient and ultimately flexible currency. Bank runs like the 1930s are a thing of the past. But that’s not to say that gold will not play a central role in the future. It will! The signs of it already happening are everywhere! Gold is not going to replace our primary medium of exchange which is paper or electronic units with those names I mentioned above. Instead, physical gold will replace paper obligations as the reserves—or store of value—within the system. Physical gold in unambiguous ownership has no counterparty. This is a much more resilient foundation than the tangled web of obligations we have today.

Can you give an example?

If you’d like to see this change in action, go to the ECB (European Central Bank) website and look at the Eurosystem’s balance sheet. On the asset side gold is on line 1 and obligations from counterparties are below it. Additionally, they adjust all their assets to the market price every three months. I have a chart of these MTM (marked to market) adjustments on my blog. Over the last decade you can see gold rising from around 30% of total reserves to over 60% while paper obligations have fallen from 70% to less than 40%. I expect this to continue until gold is more than 90% of the reserves behind the euro.

Where do you see all this money printing heading to? Will the world see hyperinflation?

Yes, this will end. I am pretty well known for predicting dollar hyperinflation. As controversial as that prediction is, I think it is a fairly certain and obvious end. I don’t like to guess at the timing because there are so many factors to consider and I’m no supercomputer, but ever since I started following this stuff I’ve always said it is overdue in the same way an earthquake can be overdue. As for other currencies, I don’t know. Perhaps yes for the UK pound and the yen, but I don’t know about the rupee. The important things to watch are the balance of trade and the government’s control over the printing press. If you’re running a trade deficit and your government can (and will) print, then you are a candidate for hyperinflation.

In that context what price do you see gold going to?

Well, I don’t see gold’s trajectory being typical of what you’d expect to see in a bull market. Instead it will be a reset of sorts, kind of like an overnight revaluation of a currency. I’m sure some of your readers have experienced a bank holiday followed by a devaluation. This will be similar. And I expect that gold will be repriced somewhere around $55,000 per ounce in today’s purchasing power. I have to add that purchasing power part because it will likely be concurrent with currency devaluation. So, in rupee terms, I guess that’s about Rs3.2 million per ounce at today’s exchange rate.

The price of gold has been rather flat lately. What are the reasons for the same? Where do you see the price of gold going over the next couple of years?

“The price of gold” is an interesting turn of phrase because I use it often to express “all things goldish” in the gold market. In today’s market, “gold” is very loosely defined. What passes for “gold” in the financial market is mostly the paper obligations of counterparties. These include forward sales, futures contracts, swaps, options and unallocated accounts. I often use the abbreviation “$PoG” to refer to the going dollar price for this loose financial “gold”.

The LBMA (London Bullion Market Association) recently released a survey of the total daily trading volume of unallocated (paper) gold. That survey revealed a trading flow of such magnitude that it compares to every ounce of gold that has ever been mined in all of history changing hands in just three months, or about 250 times faster than gold miners are actually pulling metal out of the ground. Equally stunning were the net sales during the survey period. The rate at which the banking system created “paper gold” was 11 times faster than real gold was being mined.

What is the point you are trying to make?

The point is that gold is being used by the global money market as a hard currency. But it is being treated by the marketplace as both a commodity that gets consumed and also as a fiat currency that can be credited at will. It is neither, and gold’s global traders are in for a rude awakening when they find out that ounce-denominated credits will not be exchangeable for a price anywhere near a physical ounce of gold in extremis—ironically failing at the very stage where they were expected to perform.

So what are you predicting?

But don’t get me wrong. It is not a short squeeze that I am predicting. In a short squeeze, the paper price runs up until it draws out enough real supply to cover all of the paper. But this paper will not be covered by physical gold in the end. It will be cash settled, and it will be cash settled at a price much lower than the price of a real ounce of gold, like a check written by an overstretched counterparty. It is a tough job to make my case for the future of the $PoG in just a few paragraphs. The $PoG will fall and then some short time later we will find that the market has changed out of necessity into a physical-only market at a much higher price. If you were holding paper you will be sad. If you were holding the real thing you’ll be very happy

Why is the gold price so flat these days?

Today’s surprisingly stabilized $PoG tells me that someone is throwing money into the fire to delay the inevitable. Where do I see the $PoG going over the next couple of years? Maybe to $500 or less, but you won’t be able to get any physical at that price. I think that today’s price of $1,575 is still a fantastic bargain for physical gold.

Franklin Roosevelt had confiscated all the gold that Americans had in 1933. Do you see something similar happening in the days to come?

Not at all! The purpose of the confiscation was to stop the bank run epidemic at that time. There’s no need to do it again. The dollar is no longer defined as a fixed weight of gold, so the reason for the last confiscation—and subsequent devaluation—no longer exists. Gold that’s still in the ground is a different story, however. Gold mines will likely be considered strategically important national assets after the revaluation, and will therefore fall under tight government control.

The irony of the entire situation is that a currency like “dollar” which is being printed big time has become the safe haven. How safe do you think is the safe haven?

Indeed, everyone seems to be piling into the dollar. Especially on the short end of the curve, helping drive interest rates ridiculously low. The dollar is as safe as a bomb shelter that’s rigged to blow up once everyone is “safely” inside. You can go check it out if you want to (sure, from the outside it might look like shelter), but you don’t want to be in there when it blows up. You’ve got to realize that it is both economically and politically undesirable for any currency to appreciate against its peer currencies due to its use as a safe haven. Remember the Swiss franc? As soon as it started rising due to safe haven use they started printing it back down. The dollar is no different except that it’s got a whole world full of paper obligations denominated in it. So when it blows, the fireworks will be something to behold.

What will change the confidence that people have in the dollar? Will there be some catastrophic event?

That’s the $55,000 question. It is impossible to predict the exact pin that will pop the bubble in a world full of pins, but I have an idea that it will be one of two things. I think the two most likely proximate triggers to a catastrophic loss of confidence are a major failure in the London gold market, or the U.S. government’s response to an unexpected budget crisis due to consumer price inflation. Most people who expect a catastrophic loss of confidence in the dollar seem to think it will begin in the financial markets, like a stock market crash or a Treasury auction failure or something like that. But I think it is more likely to come from where, as I like to say, the rubber meets the road. And here I’m talking about what connects the monetary world to the physical world: prices. I think these “worlds” are connected in two ways. The first is the general price level of goods and services and the second is the price of gold. If one of these two connections is broken by a failure to deliver the real-world items at the financial-system prices, then we suddenly have a real problem with the monetary side. So I think it will be a relatively quick and catastrophic event, but maybe not as dramatic as a major stock market crash. It will be confusing to most of the pundits as to what it really means, so it will take a little while for reality to sink in.

The Romans debased the denarius by almost 100% over a period of 500 years. The dollar on the other hand has lost more than 95% of its purchasing power since the Federal Reserve of United States was established in 1913, nearly 100 years back. Do you think the Federal Reserve has been responsible for the dollar losing almost all of its purchasing power in hundred years?

Yes, inflation was a lot slower in Roman times because it entailed the physical melting and reissuing of coins of a certain face value with less metal content than previous issues. This was a physical process so it occurred on a much longer time scale. The dollar, on the other hand, has lost nearly 97% of its purchasing power in roughly a hundred years. Do I think the Federal Reserve is responsible for this? Well, given that the lending/borrowing dynamic causes expansion of the money supply, I think the government and the people of the world share in the responsibility. But just because the dollar has lost 97% of its purchasing power doesn’t mean that any individual lost that much. How many people do you think are still holding onto dollars today that they earned a hundred years ago? How long would you hold dollars today? As long as the prices of things you want to buy don’t change during the time you are holding the currency, what have you lost? So imagine that you simply use currency for earning, borrowing and spending, but not for saving. Will it matter how much it falls over a hundred years? Your earning and spending will happen within a month or so, and prices won’t change much in a month. Also, your borrowing will be made easier on you as your currency depreciates. And your gold savings will rise. So with the proper use of money, there is no need for alarm if the currency is slowly falling at, say, 2% or 3% per year.

Do you see America repaying all the debt that they have taken from the rest of the world? Or will they just inflate it away by printing more and more dollars?

The debts that exist today can never be repaid in real terms. And as I mentioned before, they are all denominated in symbolic words like dollars, euro, yen, yuan and rupees. The debt of the U.S. Treasury, most of all, will of course be inflated away.

What are your views about the crisis in Europe? Will the euro hold?

Contrary to most of what we read in the Anglo-American press, I don’t think the euro currency is at risk from the sovereign debt crisis in Europe. They are two different things, the debt crisis and the euro. The euro currency faces none of the usual devaluation risks. Trade between the Eurozone and the rest of the world is balanced and the ECB has plenty of reserves. So aside from devaluation risk, which the euro doesn’t face, the only other risk is if the people decide to abandon the euro. Procedurally this would be so difficult for any country to do on a whim that I can confidently say it is virtually impossible aside from the most extreme situations like a revolutionary war or something like that. And I don’t see that happening. I think the euro survives come what may.

What does FOFOA stand for?

I remain anonymous because my blog is not about me. It is a tribute to “Another” and “Friend of Another” or “FOA” who wrote about this subject from 1997 through 2001. So FOFOA could stand for Friend of FOA or Follower of FOA or Fan of FOA. I never really stated what it stands for, so you can decide for yourself. 😉 Sincerely, FOFOA.

(The interview was originally published in the Daily News and Analysis(DNA) on July 2,2012)

(Interviewer Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Higher Oil Prices or Higher EMIs? Take your pick

Vivek Kaul

The petrol prices were raised by Rs 6.28 per litre yesterday. With taxes the total comes to Rs 7.54 per litre. Let’s try and understand what impact this increase in prices will have.

The primary beneficiary of this increase will be the oil marketing companies like Indian Oil, Bharat Petroleum and Hindustan Petroleum. The companies had been losing Rs 6.28 per litre of petrol they sold. Since December, when prices were last raised the companies had lost $830million in total. With the increase in prices the companies will not lose money when they sell petrol.

The increase in price will have no impact on the fiscal deficit of the government. The fiscal deficit is the difference between what the government spends and what it earns. The government does not subsidize the oil marketing companies for the losses they make on selling petrol.

It subsidizes them for losses made on selling diesel, kerosene and LPG, below cost.

The losses on account of this currently run at Rs 512 crore a day. The loss last year to these companies because of selling diesel, kerosene and LPG below cost was at Rs 138,541crore. They were compensated for this loss by the government. Out of this the government got the oil and gas producing companies like ONGC, Oil India Ltd and GAIL to pick up a tab of Rs 55,000 crore. The remaining Rs 83,000 odd crore came from the coffers of the government.

What is interesting that when the budget was presented in March, the oil subsidy bill for the year 2011-2012 (from April 1, 2011 to March 31,2012) was expected to be at around Rs 68,500 crore. The final number was Rs 14,500 crore higher.

The losses for this financial year (from April 1, 2012 to March 31,2012) are expected to be at Rs Rs. 193,880 crore. If the losses are divided between the government and the oil and gas producing companies in the same ratio as last year, then the government will have to compensate the oil marketing companies with around Rs 1,14,000 crore. The remaining money will come from the oil and gas producing companies.

The trouble is in two fronts. It will pull down the earnings of the oil and gas producing companies. But that’s the smaller problem. The bigger problem is it will push up the fiscal deficit. If we look at the assumptions made in the budget for the current financial year, the oil subsidies have been assumed at Rs Rs 43,580 crore. If the government has to compensate the oil marketing companies to the extent of Rs 1,14,000 crore, it means that the fiscal deficit will be pushed up by around Rs 70,000 crore more (Rs 1,14,000crore minus Rs 43,580 crore), assuming all other expenses remain the same.

A higher fiscal deficit would mean that the government would have to borrow more. A higher government borrowing will ‘crowd-out’ the private borrowing and push interest rates higher. This would mean higher equated monthly installments(EMIs) for people who have loans to pay off or are even thinking of borrowing.

The only way of bringing down the interest rates is to bring down the fiscal deficit. The fiscal deficit target for the financial year 2012-2013 has been set at Rs 5,13,590 crore. The government raises this money from the financial system by issuing bonds which pay interest and mature at various points of time. Of this amount that the government will raise, it will spend Rs 3,19,759 crore to pay interest on the debt that it already has. Rs 1,24,302 crore will be spent to payback the debt that was raised in the previous years and matures during the course of the year 2012-2013. Hence a total of Rs 4,44,061 crore or a whopping 86.5% of the fiscal deficit will be spent in paying interest on and paying off previously issued debt. This is an expenditure that cannot be done away with.

The other major expenditure for the government during the course of the year are subsidies. The total cost of subsidies during the course of this year has been estimated to be at Rs Rs 1,90,015 crore. The subsidies are basically of three kinds: oil, food and petroleum. The food subsidy is at Rs 75,000 crore. This is a favourite with Sonia Gandhi and hence cannot be lowered. And more than that there is a humanitarian angle to it as well.

The fertizlier subsidies have been estimated at Rs 60,974 crore. This is a political hot potato and any attempts to cut this in the pst have been unsuccessful and have had to be rolled back. There are other subsidies amounting to Rs 10,461 crore which are minuscule in comparison to the numbers we are talking about.

This leaves us with oil subsidies which have been estimated to be at Rs 43,580 crore. This as we see will be overshot by a huge level, if oil prices continue to be current levels. Even if prices fall a little, the subsidy will not come down by much. .

Hence if the government has to even maintain its deficit (forget bringing it down) the only way out currently is to increase the price of diesel, LPG and kerosene. Diesel is a transport fuel and an increase in its price will push prices inflation in the short term. But maintain the fiscal deficit will at least keep interest rates at their current levels and not push them up from their already high levels.

If the government continues to subsidize diesel, LPG and kerosene, interest rates are bound to go up because it will have to borrow more. This will mean higher EMIs for sure. It would also mean businesses postponing expansion because higher interest rates would mean that projects may not be financially viable. It would also mean people borrowing lesser to buy homes, cars and other things, leading to a further slowdown in a lot of sectors. In turn it would mean lower economic growth.

That’s the choice the government has to make. Does it want the citizens of this country to pay higher fuel and gas prices? Or does it want them to pay higher EMIs? There is no way of providing both.

(The article originally appeared at www.rediff.com on May 24,2012. http://www.rediff.com/business/slide-show/slide-show-1-special-higher-oil-prices-or-higher-emis-take-your-pick/20120524.htm)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Petrol bomb is a dud: If only Dr Singh had listened…

Vivek Kaul

The Congress led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government finally acted hoping to halt the fall of the falling rupee, by raising petrol prices by Rs 6.28 per litre, before taxes. Let us try and understand what will be the implications of this move.

Some relief for oil companies:

The oil companies like Indian Oil Company (IOC), Bharat Petroleum (BP) and Hindustan Petroleum(HP) had been selling oil at a loss of Rs 6.28 per litre since the last hike in December. That loss will now be eliminated with this increase in prices. The oil companies have lost $830million on selling petrol at below its cost since the prices were last hiked in December last year. If the increase in price stays and is not withdrawn the oil companies will not face any further losses on selling petrol, unless the price of oil goes up and the increase is not passed on to the consumers.

No impact on fiscal deficit:

The government compensates the oil marketing companies like Indian Oil, BP and HP, for selling diesel, LPG gas and kerosene at a loss. Petrol losses are not reimbursed by the government. Hence the move will have no impact on the projected fiscal deficit of Rs 5,13,590 crore. The losses on selling diesel, LPG and kerosene at below cost are much higher at Rs 512 crore a day. For this the companies are compensated for by the government. The companies had lost Rs 138,541 crore during the last financial year i.e.2011-2012 (Between April 1,2011 and March 31,2012).

Of this the government had borne around Rs 83,000 crore and the remaining Rs 55,000 crore came from government owned oil and gas producing companies like ONGC, Oil India Ltd and GAIL.

When the finance minister Pranab Mukherjee presented the budget in March, the oil subsidies for the year 2011-2012 had been expected to be at Rs Rs 68,481 crore. The final bill has turned out to be at around Rs 83,000 crore, this after the oil producing companies owned by the government, were forced to pick up around 40% of the bill.

For the current year the expected losses of the oil companies on selling kerosene, LPG and diesel at below cost is expected to be around Rs 190,000 crore. In the budget, the oil subsidy for the year 2012-2013, has been assumed to be at Rs 43,580 crore. If the government picks up 60% of this bill like it did in the last financial year, it works out to around Rs 114,000 crore. This is around Rs 70,000 crore more than the oil subsidy that the government has budgeted for.

Interest rates will continue to remain high

The difference between what the government earns and what it spends is referred to as the fiscal deficit. The government finances this difference by borrowing. As stated above, the fiscal deficit for the year 2012-2013 is expected to be at Rs 5,13,590 crore. This, when we assume Rs 43,580crore as oil subsidy. But the way things currently are, the government might end up paying Rs 70,000 crore more for oil subsidy, unless the oil prices crash. The amount of Rs 70,000 crore will have to be borrowed from financial markets. This extra borrowing will “crowd-out” the private borrowers in the market even further leading to higher interest rates. At the retail level, this means two things. One EMIs will keep going up. And two, with interest rates being high, investors will prefer to invest in fixed income instruments like fixed deposits, corporate bonds and fixed maturity plans from mutual funds. This in other terms will mean that the money will stay away from the stock market.

The trade deficit

One dollar is worth around Rs 56 now, the reason being that India imports more than it exports. When the difference between exports and imports is negative, the situation is referred to as a trade deficit. This trade deficit is largely on two accounts. We import 80% of our oil requirements and at the same time we have a great fascination for gold. During the last financial year India imported $150billion worth of oil and $60billion worth of gold. This meant that India ran up a huge trade deficit of $185billion during the course of the last financial year. The trend has continued in this financial year. The imports for the month of April 2012 were at $37.9billion, nearly 54.7% more than the exports which stood at $24.5billion.

These imports have to be paid for in dollars. When payments are to be made importers buy dollars and sell rupees. When this happens, the foreign exchange market has an excess supply of rupees and a short fall of dollars. This leads to the rupee losing value against the dollar. In case our exports matched our imports, then exporters who brought in dollars would be converting them into rupees, and thus there would be a balance in the market. Importers would be buying dollars and selling rupees. And exporters would be selling dollars and buying rupees. But that isn’t happening in a balanced way.

What has also not helped is the fact that foreign institutional investors(FIIs) have been selling out of the stock as well as the bond market. Since April 1, the FIIs have sold around $758 million worth of stocks and bonds. When the FIIs repatriate this money they sell rupees and buy dollars, this puts further pressure on the rupee. The impact from this is marginal because $758 million over a period of more than 50 days is not a huge amount.

When it comes to foreign investors, a falling rupee feeds on itself. Lets us try and understand this through an example. When the dollar was worth Rs 50, a foreign investor wanting to repatriate Rs 50 crore would have got $10million. If he wants to repatriate the same amount now he would get only $8.33million. So the fear of the rupee falling further gets foreign investors to sell out, which in turn pushes the rupee down even further.

What could have helped is dollars coming into India through the foreign direct investment route, where multinational companies bring money into India to establish businesses here. But for that the government will have to open up sectors like retail, print media and insurance (from the current 26% cap) more. That hasn’t happened and the way the government is operating currently, it is unlikely to happen.

The Reserve Bank of India does intervene at times to stem the fall of the rupee. This it does by selling dollars and buying rupee to ensure that there is adequate supply of dollars in the market and the excess supply of rupee is sucked out. But the RBI does not have an unlimited supply of dollars and hence cannot keep intervening indefinitely.

What about the trade deficit?

The trade deficit might come down a little if the increase in price of petrol leads to people consuming less petrol. This in turn would mean lesser import of oil and hence a slightly lower trade deficit. A lower trade deficit would mean lesser pressure on the rupee. But the fact of the matter is that even if the consumption of petrol comes down, its overall impact on the import of oil would not be that much. For the trade deficit to come down the government has to increase prices of kerosene, LPG and diesel. That would have a major impact on the oil imports and thus would push down the demand for the dollar. It would also mean a lower fiscal deficit, which in turn will lead to lower interest rates. Lower interest rates might lead to businesses looking to expand and people borrowing and spending that money, leading to a better economic growth rate. It might also motivate Multi National Companies (MNCs) to increase their investments in India, bringing in more dollars and thus lightening the pressure on the rupee. In the short run an increase in the prices of diesel particularly will lead higher inflation because transportation costs will increase.

Freeing the price

The government had last increased the price of petrol in December before this. For nearly five months it did not do anything and now has gone ahead and increased the price by Rs 6.28 per litre, which after taxes works out to around Rs 7.54 per litre. It need not be said that such a stupendous increase at one go makes it very difficult for the consumers to handle. If a normal market (like it is with vegetables where prices change everyday) was allowed to operate, the price of oil would have risen gradually from December to May and the consumers would have adjusted their consumption of petrol at the same pace. By raising the price suddenly the last person on the mind of the government is the aam aadmi, a term which the UPAwallahs do not stop using time and again.

The other option of course is to continue subsidize diesel, LPG and kerosene. As a known stock bull said on television show a couple of months back, even Saudi Arabia doesn’t sell kerosene at the price at which we do. And that is why a lot of kerosene gets smuggled into neighbouring countries and is used to adulterate diesel and petrol.

If the subsidies continue it is likely that the consumption of the various oil products will not fall. And that in turn would mean oil imports would remain at their current level, meaning that the trade deficit will continue to remain high. It will also mean a higher fiscal deficit and hence high interest rates. The economic growth will remain stagnant, keeping foreign businesses looking to invest in India away.

Manmohan Singh as the finance minister started India’s reform process. On July 24, 1991, he backed his “then” revolutionary proposals of opening up India’s economy by paraphrasing Victor Hugo: “No power on Earth can stop an idea whose time has come.”

Good economics is also good politics. That is an idea whose time has come. Now only if Mr Singh were listening. Or should we say be allowed to listen..

(The article originally appeared at www.firstpost.com on May 24,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/petrol-bomb-is-a-dud-if-only-dr-singh-had-listened-319594.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

It’s not Greece: Cong policies responsible for rupee crash

Vivek Kaul

All is well in India under the rule of the “Gandhi” family. That’s what the Finance Minister Pranab Mukjerjee has been telling us. And the rupee’s fall against the dollar is primarily because of problems in Greece. And Spain. And Europe. And other parts of the world. As I write this one dollar is worth around Rs 55 (actually Rs 54.965 to be precise, but we can ignore a few decimal points). The rupee has fallen around 22% in value against the dollar in the last one year.

The larger view among analysts and experts who track the foreign exchange market is that a dollar will soon be worth Rs 60. And by then there might be problems in some other part of the world and the rupee’s fall might be blamed on the problems there. As a late professor of mine used to say, with a wry smile on his face “Since we are all born on this mother earth, there is some sort of symbiosis between us.”

So let’s try and understand why the underlying logic to the rupee’s fall against the dollar is not as simple as it is made out to be.

Dollar is the safe haven

As economic problems have come to the fore in Europe (As I have highlighted in If PIIGS have to fly they will have to exit the Euro http://www.firstpost.com/world/if-piigs-have-to-fly-they-will-need-to-exit-the-euro-314589.html) the large institutional investors have moved out of the Euro into the dollar. A year back one dollar was worth €0.71, now it’s worth €0.78. So the dollar has gained against the Euro, no doubt.

But the argument being made is that this is global trend and that dollar has gained in value against lot of other major currencies. Is that true? A year back one dollar was worth 0.88 Swiss Francs, now it is worth 0.93 Swiss Francs. So it has gained in value against the Swiss currency.

What about the British pound? A year back the dollar was worth £0.62, now it’s worth £0.63. Hence the dollar has barely moved against the pound. A dollar was worth around 82 Japanese yen around a year back. Now it’s worth around 79.5yen. It has lost value against the Japanese yen. The dollar has gained in value against the Brazilian Real. It was worth around 1.63real a year back. It is now worth over 2 real. So yes, the dollar has gained in value against the other currencies but not against all currencies.

What is ironic is that the world at large is considering dollar to be a safe haven and moving money into it, by buying bonds issued by the American government. The debt of the US government is now around $14.6trillion, which is almost equal to the US gross domestic product of $15trillion. But since everyone considers it to be a safe haven it has become a safe haven.

But let’s get back to the point at hand. So, not all currencies have lost value against the dollar and those that have lost value, have lost it in varying degrees. This tells us that there are other individual issues at play as well when it comes to currencies losing value against the dollar.

What is happening in India?

The Indian government has been spending much more money than it has been earning over the last few years. In other words the fiscal deficit of the government has been on its way up. For the financial year 2007-2008 (i.e. the period between April 1,2007 and March 31, 2008) the fiscal deficit stood at Rs 1,26,912 crore. This shot up to Rs 5,21,980 crore for the financial year 2011-2012. In a time frame of five years the fiscal deficit has shot up by nearly 312%. During the same period the income earned by the government has gone up by only 36% to Rs 7,96,740 crore. The fiscal deficit targeted for the current financial year 2012-2013(i.e. between April 1, 2012 and March 31,2013) is a little lower at Rs 5,13,590 crore. The huge increase in fiscal deficit has primarily happened because of the subsidy on food, fertilizer and petroleum.

The tendency to overshoot

Also it is highly likely that the government might overshoot its fiscal deficit target like it did last year. In his budget speech last year Pranab Mukherjee had set the fiscal deficit target for the financial year 2011-2012, at 4.6% of GDP. He missed his target by a huge margin when the real number came in at 5.9% of GDP. The major reason for this was the fact that Mukherjee had underestimated the level of subsidies that the government would have to bear. He had estimated the subsidies at Rs 1,43,750 crore but they ended up costing the government 50.5% more at Rs 2,16,297 crore.

Generally all the three subsidies of food, fertilizer and petroleum are underestimated, but the estimates on the oil subsidies are way off the mark. For the year 2011-2012, oil subsidies were assumed to be at Rs 23,640crore. They came in at Rs 68,481 crore. This has been the case in the past as well. In 2010-2011 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2010 and March 31, 2011) he had estimated the oil subsidies to be at Rs 3108 crore. They finally came in 20 times higher at Rs 62,301 crore. Same was the case in the year 2009-2010 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2009 and March 31, 2010). The estimate was Rs 3109 crore. The real bill came in nearly eight times higher at Rs 25,257 crore (direct subsidies + oil bonds issued to the oil companies).

The increasing fiscal deficit

The fiscal deficit has gone up over the years primarily because an increase in expenditure has not been matched with an increase in revenue. Revenue for the government means various forms of taxes and other forms of revenue like selling stakes in public sector enterprises.

The fact of the matter is that Indians do not like to pay income tax or any other kind of tax. This a throw back from the days of the high income tax rate in the 60s, 70s and the 80s, when a series of Finance Ministers (from C D Deshmukh to Yashwantrao Chavan and bureaucrats like Manmohan Singh) implemented high income tax rates in the hope that taxing the “rich” would solve all of India’s problems.

In the early 1970s the highest marginal rate of tax was 97%. The story goes that JRD Tata sold some property every year to pay taxes (income tax plus wealth tax) which worked out to be more than his yearly income. Of course everybody was not like the great JRD, and because of the high tax rates implemented by various Congress governments over the years, a major part of the Indian economy became black. Dealings were carried out in cash. Transactions were made but they were never recorded, because if they were recorded tax would have to be paid on them.

A series of exemptions were granted to corporate India as well, and companies like Reliance Industries did not pay any income tax for years. As a result of this India and Indians did not and do not like paying tax.

Various lobbies have also emerged which have ensured that those that they represent are not taxed. As Professor Amartya Sen wrote in a column in The Hindu earlier this year “It is worth asking why there is hardly any media discussion about other revenue-involving problems, such as the exemption of diamond and gold from customs duty, which, according to the Ministry of Finance, involves a loss of a much larger amount of revenue (Rs.50,000 crore per year)”.

As he further points out “The total “revenue forgone” under different headings, presented in the Ministry document, an annual publication, is placed at the staggering figure of Rs.511,000 crore per year. This is, of course, a big overestimation of revenue that can be actually obtained (or saved), since many of the revenues allegedly forgone would be difficult to capture — and so I am not accepting that rosy evaluation.”

But even with the overestimation the fact of the matter is that a lot of tax that can be collected from those who can pay is not being collected, and that of course means a higher fiscal deficit.

The twin deficit hypothesis

The hypothesis basically states that as the fiscal deficit of the country goes up its trade deficit (i.e. the difference between its exports and imports) also goes up. Hence when a government of a country spends more than what it earns, the country also ends up importing more than exporting.

But why is that? The fiscal deficit goes up because the increase in expenditure is not matched by an increase in taxes. This leaves people with a greater amount of money in their hands. Some portion of this money is used towards buying goods and services, which might be imported from abroad. This leads to greater imports and thus a higher trade deficit. The situation in India is similar. The government of India has been spending more than it has been earning without matching the increase in income with higher taxes, which in turn has led to increasing incomes and that to some extent has been responsible for an increase in Indian imports. But that could have hardly been responsible for the trade deficit of $185billion that India ran in 2011-2012. The imports for the month of April 2012 were at $37.9billion, nearly 54.7% more than the exports which stood at $24.5billion. So the trend has continued even in this financial year.

The golden oil shock

India exports a major part of its oil needs. On top of that it is obsessed with gold. Last year we imported 1000 tonnes of it. Very little of both these commodities priced in dollars is dug up in India. So we have to import them.

This pushes up our imports and makes them greater than our exports. These imports have to be paid for in dollar. When payments are to be made importers buy dollars and sell rupees. When this happens, the foreign exchange market has an excess supply of rupees and a short fall of dollars. This leads to rupee losing value against the dollar. In case our exports matched our imports, then exporters who brought in dollars would be converting them into rupees, and thus there would be a balance in the market. Importers would be buying dollars and selling rupees. And exporters would be selling dollars and buying rupees. But that isn’t happening in a balanced way.

This to some extent explains the current rupee dollar rate of $1 = Rs 55. The Reserve Bank of India does intervene at times to stem the fall of the rupee. This it does by selling dollars and buying rupee. But the RBI does not have an unlimited supply of dollars and hence cannot keep intervening indefinitely.

As mentioned earlier the major part of the trade deficit is because of the fact that we need to import oil. Oil prices have been high for the last few years, though recently they have fallen. Oil is sold in dollars. Hence when India needs to buy oil it needs to pay in dollars. But with the rupee constantly losing value against the dollar, it means that Indian companies have to more per barrel of oil in rupees.

The government of India does not pass on a major part of the increase in the price of oil to the end consumer and hence subsidizes the prices of diesel, LPG, kerosene etc. This means that the oil companies have to sell these products at a loss to the consumer. The government in turn compensates these companies for the loss. This leads to the expenditure of the government going up and hence it incurs a higher fiscal deficit.

No passing the buck

If the government had not subsidized prices of oil products and passed them onto the end consumer, their consumption would have come down. With prices of oil products not rising as much as they should people have not adjusted their consumption accordingly. An increase in price typically leads to a fall in demand. If the increased price of oil had been passed onto the end consumer, the demand for oil would have come down. This would have meant that a fewer number of dollars would have been required to pay for the oil being imported, in turn leading to a lower trade deficit and hence lesser pressure on the rupee-dollar rate.

So let me summarise the argument I am making. The higher fiscal deficit in the form of subsidies has pushed up the trade deficit which in turn has led to rupee losing value against the dollar. The solution is to get consumers to pay the “right” price. With this the fiscal deficit can be brought down to some extent. If these products are priced correctly, their consumption is likely to come down as well in the near future, given that their prices will go up. Lower consumption is likely to lead to lower imports and thus a lower trade deficit. A lower trade deficit would also mean that the fall of the rupee against the dollar may stop. This in turn would mean a lower price for the oil we import in rupee terms and that in turn help overall economic growth. A lower fiscal deficit will lead to lower government borrowing and hence lesser “crowding out” and so lower interest rates, which might get corporates and individuals interested in borrowing again.

The long term solution

What has been suggested above is a short term solution, which given the way the Congress led UPA government operates is unlikely to be implemented. The main problem is that while it’s quite a noble idea to provide subsidies in the form of food, fertilizer, kerosene etc to the India’s poor, it has to be matched with an increase in taxes. An increase in income taxes rates isn’t going to help much because only a minuscule portion of India pays income tax (basically the salaried class).

What is needed is to get larger number of people to pay tax to pay for all the subsidies that are doled out. This can be done by simplifying the income tax act. This was tried when the government tried to come up with the Direct Taxes Code(DTC), which was very simple and straightforward and had done away with most exemptions. In its original form the DTC was a pleasure to read. But of course if it had been implemented scores of people who do not pay income tax would have to pay income tax. In its current form the DTC is another version of Income Tax Act.

Another way is to target specific communities of people who do not pay income tax even though they earn a huge amount of money, but all in “black”. For starters the targeting property dealers that line up almost every street in Delhi might be a good idea. Once, people see that the government is serious about collecting taxes, they are more likely to pay up than not. And there is no better way than starting with the capital.

(The article originally appeared at www.firstpost.com on May 23,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/dont-blame-greece-cong-policies-responsible-for-rupees-crash-318280.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and he can be reached at [email protected])