Over the Republic Day long-weekend, I was having a discussion with a friend on what might seem to be a rather trivial topic. We got into a discussion on why progeny of famous parents are never really as good and as famous, as their parents.

There are many examples of this phenomenon. Dev Anand’s son Suneil never ever came close to the stardom of his father. He acted in a few films over a period of two decades. All of these movies flopped. Sunil Gavaskar’s son Rohan represented India in one day international matches but never got around to playing a Test match. None of Bob Dylan’s progeny have come close to making music that is as good as what Mr Zimmerman (Robert Zimmerman is Bob Dylan’s real name) has over the years. The popularity of the Gandhi family with the citizens of this country has gone down with every generation, and so has their political acumen. There are many more examples that one could come up with.

This is basically what we were discussing. My friend firmly believed that progeny of famous parents never came to be anywhere close to be as famous as their parents were. I said there are always exceptions to everything.

My friend who had aspirations of studying economics, until the more practical considerations of getting an MBA degree took over, felt that what we were discussing was an excellent example of what economists and mathematicians call regression to the mean.

And this brings us to Francis Galton who lived in the nineteenth and the early twentieth century, and among other things was also a statistician. Galton measured the height of children and came across what was then a remarkable discovery.

As Jordan Ellbenberg writes in How Not to Be Wrong – The Hidden Maths of Everyday Life: “As Galton and everyone else already knew, tall parents tend to have tall children…But now here is Galton’s remarkable discovery: those children are not likely to be as tall as their parents. The same goes for short parents, in the opposite direction; their kids will tend to be short, but not as short as they themselves are. Galton had discovered the phenomenon now called regression to the mean.”

As Galton wrote in Natural Inheritance: “However paradoxical it may appear at first sight, it is theoretically a necessary fact, and one that is clearly confirmed by observation, that the Stature of the adult offspring must on the whole, be more mediocre than the stature of their Parents.”

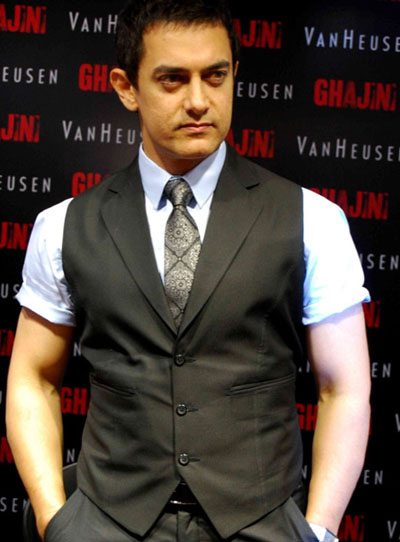

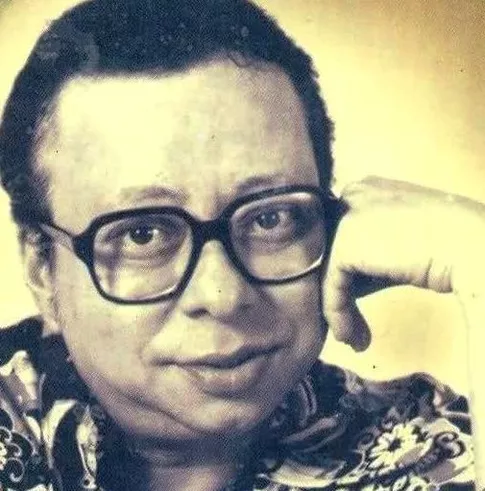

Galton further reasoned that what was true for height must also be true for mental achievement. As Ellenberg writes: “And this conforms with common experience; the children of a great composer, or scientist, or political leader, often excel in the same field, but seldom so much as their illustrious parents.” A rare exception to this is the music director RD Burman, who achieved as much as his father SD Burman did, if not more.

Interestingly, there are examples in the other direction as well or as Ellenberg puts it, the children of short parents are not as short as their parents. This also works when it comes to achievement. Here are a few examples.

The test cricketer Cheteshwar Puajara’s father Arvind played a few Ranji trophy matches but did not make it to the big league. And so did his uncle Bipin. The Bollywood actor Govinda’s father Arun Ahuja starred as a hero in films in the late 1930s and forties, but never came to achieve the stardom that his son eventually did.

The music director AR Rahman’s father RK Shekhar was a music director of some repute having composed music for more than fifty films. He was also a music conductor. He never came close to achieving the kind of success that Rahman has, both nationally as well as internationally.

And that, dear reader, is something worth thinking about.

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He can be reached at [email protected])

The column originally appeared in the Bangalore Mirror on February 3, 2016