The devil, as they say, is in the detail.

On Page 195 of the Reserve Bank of India’s latest annual report released on August 30, 2017, lies the answer to the question, a large part of India has been asking for close to ten months.

Has demonetisation been a success or a failure? As per the RBI data released in the annual report, it is safe to say that demonetisation has been a failure of epic proportions.

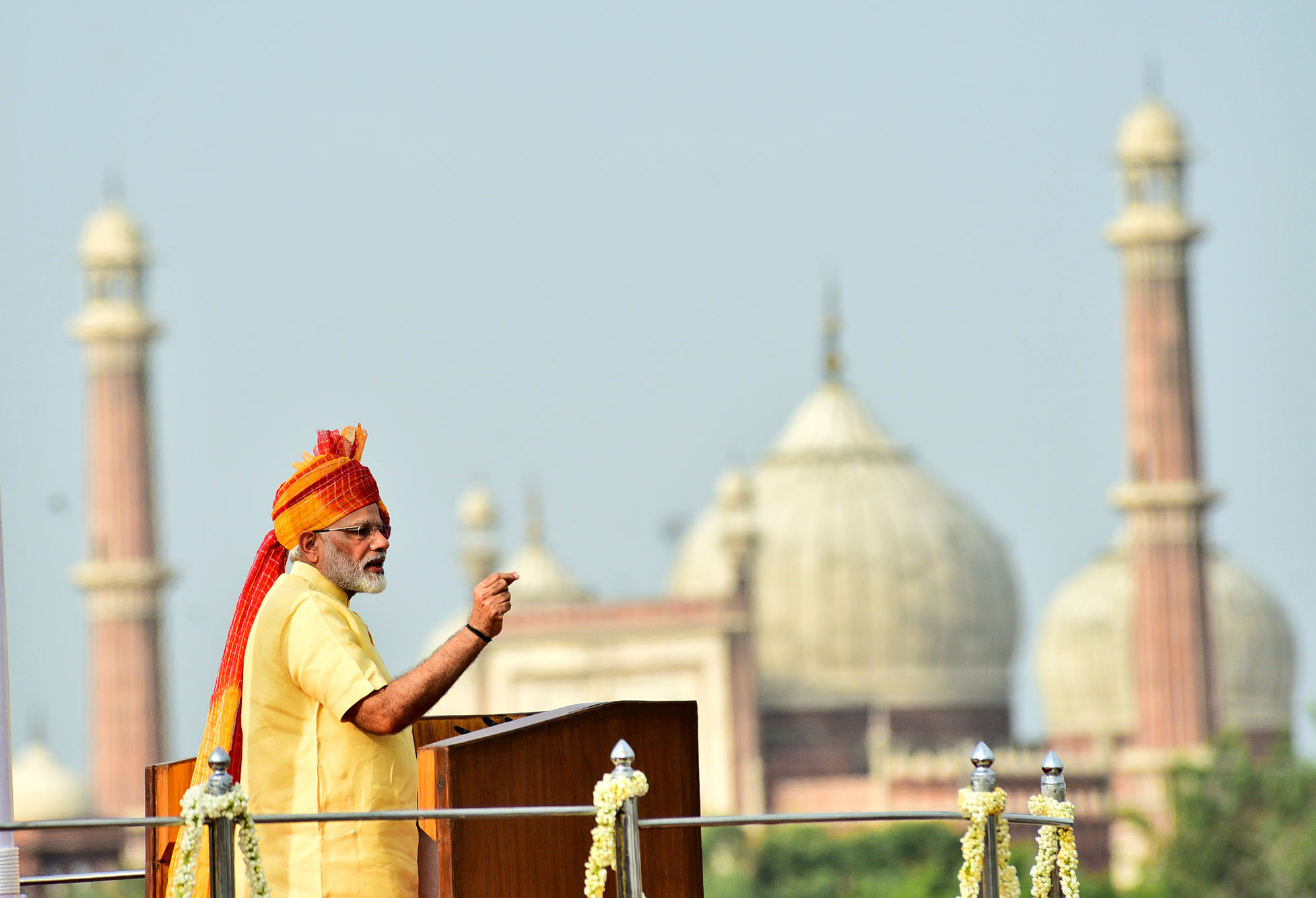

On November 8, last year, the Narendra Modi government decided to demonetise Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes, which were worth Rs 15.44 trillion notes in total. The idea was to attack both fake currency as well as black money or unaccounted wealth. The prime minister said so in his address to the nation announcing the demonetisation decision.

This was backed up by the government press release accompanying the decision. Black money is essentially money that has been earned but on which taxes haven’t been paid.

From the midnight between November 8 and November 9, 2016, the Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes, were not worth anything. The people holding these notes had to deposit them in their bank accounts. This money could later be withdrawn, though there were restrictions on the amount of the money that could be withdrawn immediately.

The hope was that black money held in the form of cash wouldn’t be deposited into banks, given that people holding this money wouldn’t want to be identified. In the process, a humongous amount of black money would be destroyed.

The RBI Annual Report on Page 195 says that demonetised notes worth Rs 15.28 trillion were deposited into banks, up to June 30, 2017. This basically means that almost 99 per cent of the demonetised money was deposited into banks. Hence, almost all the black money held in the form of cash, also made it back into the banks and wasn’t really destroyed, as had been hoped.

The conventional explanation for this is that most people who had black money found other people, who did not have black money, to deposit money into the banking system.

As far as detecting fake currency is concerned, nothing much seems to have happened on this front. Data from the RBI annual report tells us that the number of fake Rs 500 (old series) and Rs 1,000 notes detected between April 2016 to March 2017 was 5,73,891. The total number of demonetised notes stood at 24.02 billion. This basically means that as a proportion the fake notes identified between April 2016 to March 2017 stands close to 0 per cent of the demonetised notes.

The total number of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 fake notes detected between April 2015 and March 2016, stood at 4,04,794. And this happened without any demonetisation. Hence, demonetisation has failed on its two major objectives.

The funny thing is that there were no estimates of how much of black money was held in the form of cash. The government admitted to the same as well, after having made the decision to demonetise. The finance minister Arun Jaitley said so in a written reply to a question in the Lok Sabha (one of the Houses of the Indian Parliament) on December 16, 2016, where he said: “There is no official estimation of the amount of black money either before or after the Government’s decision of 8th November 2016 declaring that bank notes of denominations of the existing series of the value of five hundred rupees and one thousand rupees shall cease to be legal tender with effect from 9th November 2016.”

The search and seize operations carried out by the Income Tax Department (popularly referred to as Income Tax raids) suggested that people tend to hold around 5 per cent of their black money in the form of cash.

But even this lack of data in public, did not stop economists from coming up with their own set of numbers, trying to defend this decision of the Modi government. Leading this charge was Columbia University economist Jagdish Bhagwati (along with two co-authors), who in a column in the Mint newspaper on December 27, 2016, wrote: “Suppose we accept the estimate that one-third of the approximately Rs15 trillion in demonetised notes is black money.” These economists did not bother to explain, what logic did they base their assumption on.

Demonetisation has badly hit India’s large cash economy. As per the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (the labour wing of the Bharatiya Janata Party, which currently governs the country): “As many as 2.5 lakh units in unorganised sector were closed and the real estate sector was badly affected where a large number of workers got unemployed.”

Agriculture trade, a sector which largely operates on cash, has been badly impacted as well, with farmers not getting adequate compensation primarily for vegetables and pulses, they had grown. This has led to farmers protests across the country, which has in turn led to several state governments waiving off farm loans.

Over and above this, demonetisation caused a huge cash shortage with people having to spend many days standing in ATM lines trying to withdraw their own money. Many people even died in the process.

As far as the Modi government is concerned they are unlikely to admit that demonetisation was a big mistake and will continue to put a positive spin around it, as they have from November 2016. Things will not change on that front.

To conclude, no relatively healthy economy in the past, has carried out demonetistaion. As the latest Economic Survey of the government of India points out: “India’s demonetisation is unprecedented in international economic history, in that it combined secrecy and suddenness amidst normal economic and political conditions. All other sudden demonetisations have occurred in the context of hyperinflation, wars, political upheavals, or other extreme circumstances.”

And the real costs of this unprecedented event are only just starting to come out.

A slightly shorter version of this column appeared on BBC.com.