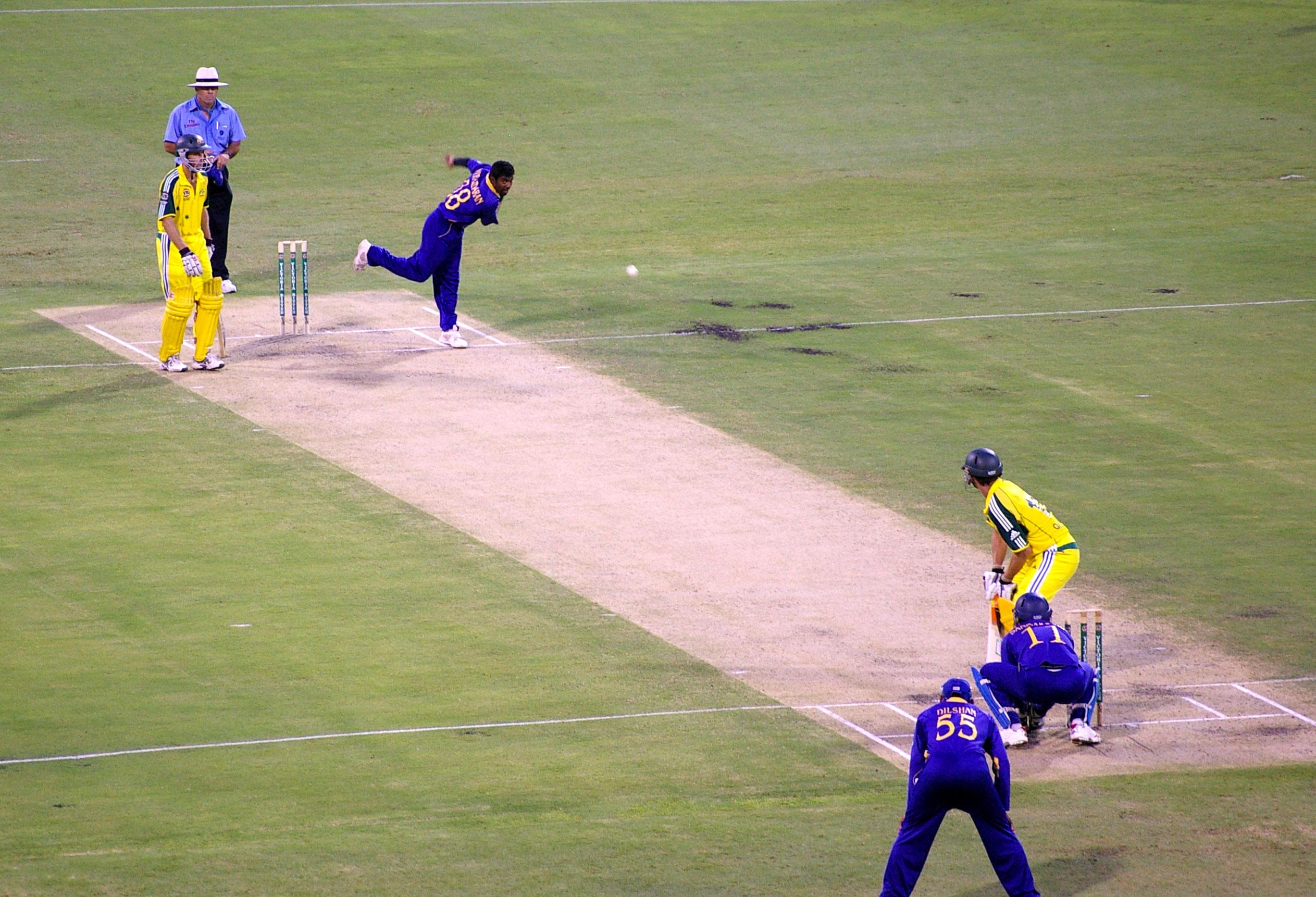

Over the four-day long weekend between March 24 and March 27, two exciting cricket matches were played. The Indian cricket team won both the matches.

I saw both these cricket matches end to end, but I had my TV on mute. I do this because I strongly feel that on most occasions TV commentary does not add any value to the visuals on the screen. And honestly, if there was an option which allowed me to just listen to the noise coming from the stadium, without the commentary, I would choose it.

Most cricket commentary and analysis is full of hindsight bias. And what is hindsight bias? As Jason Zweig writes in The Devil’s Financial Dictionary: “Only perhaps a half dozen market pundits saw the financial crisis coming before 2008, but you can’t swing a Hermès necktie on Wall Street without hitting someone who claims to have predicted it. That is typical of hindsight bias, the mechanism in the human mind that makes surprises vanish. Once you learn what did happen, your mind tricks you into believing that you knew it would happen.”

Take the match between India and Bangladesh. Bangladesh had almost won the match and needed to score two runs of three balls. They lost three wickets of the last three balls and India won the match by one run. Of these three wickets, two batsman got out trying to finish the game by hitting a six.

I think the Indian captain Mahindra Singh Dhoni summarised the situation best in what he said after the match: “At times, you look to finish it with a big shot. When you are batting well, you go for it. It is a learning for him [Mahmudullah] and others who finish games. That is what cricket is all about. If it had gone for six, everybody would have said what a shot.”

The trouble is that the Bangladeshi batsman Mahmudullah got out trying to hit a six and win the game for his team. And the commentators immediately pounced on him and declared that he should not have gone for the glory shot. The Bangladeshi cricketers were also called chokers. Nevertheless, if Mahmudullah had been able to hit a six, the same set of commentators would have had good things to say about him.

As Dhoni further said: “In-form batsmen often try to play big shots to finish the game. If that shot by Mahmudullah had crossed the ropes, he would have been hailed as a courageous gutsy batsman. Now he will face criticism for playing such a shot.”

An almost similar thing was at view when Virat Kohli single-handedly helped India beat Australia. After India won, the commentators kept talking about his aggression and how it helped him play the innings that he did. The point is that if he had gotten out, the same aggression would have been blamed for his and the Indian team’s downfall.

The outcome of the game determines the analysis that follows. And the confidence with which the commentators speak makes you believe that they had really seen it coming. Of course, the fact that they have played the game in the past, adds to the confidence that they are able to project. But do they really see it coming? I don’t think so.

They day batsmen get out trying to hit shots, the analysis blames them for hitting rash shots. On days these shots come off, the commentators feel that taking a certain amount of risk is a very important part of modern day cricket.

In fact, hindsight bias impact even the commentary that accompanies every ball that is bowled and not just the analysis accompanying the overall result of the match. In the India versus Australia game, I was listening to the Hindi commentary and I think Shoaib Akhtar was speaking (though I am not sure about this) at that point of time. Virat Kohli hit a ball in the air and from the initial looks of it, it seemed that the ball would not cross the boundary and an Aussie fielder would take the catch.

So the first thing Akhtar said was “Kharab shot (A bad shot)”. Just a second later the ball had sailed across the boundary, Kohli had hit a six, and Akhtar said: “behtareen shot (what a good shot)”. Akhtar’s commentary immediately took into account the end result (i.e. Kohli hitting a six) and what was a bad shot suddenly became a terrific one.

The question is why does this happen? The Nobel Prize winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman has an answer for this in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow. As he writes: “The mind that makes up narratives about the past is a sense-making organ. When an unpredicted event occurs we immediately adjust our view of the world to accommodate the surprise. Imagine yourself before a football game between two teams…Now the game is over, and one team trashed the other. In your revised model of the world, the winning team is much stronger than the loser, and your view of the past as well as the future has been altered by that new perception.”

Then there is this other point that Dan Gardener writes about in Future Babble: “After a football team wins a game, for example, all fans are likely to remember themselves giving the teams better odds to win than they actually did. But researchers found that they could amplify this bias simply by asking fans to construct explanations for why the team won.”

This is precisely what happens to cricket commentators and the analysis that they have to offer after any game of cricket is over. Given that they have offer explanations of why the team wining, actually won, they end up amplifying the hindsight bias.

Depending on the result, the commentators offer an analysis. Some of it can be as banal as the winning side fielded better, batted better and bowled better (Something that Mohammed Azharuddin used to say all the time in his post-match comments when he was the India captain).

This is not to say that this analysis is incorrect, but why do we need a commentator to tell us this. It is very obvious. On most occasions a team that bats better, bowls better and fields better, is likely to win.

The hindsight bias also impacts stock market experts and analysts who try and make sense of the stock market on a regular basis. After a crash you will hear all kinds of pundits trying to claim they had seen it coming all along. And believe me they will make a very compelling case for it.

Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind what Jason Zweig says. As he writes: “Contrary to popular cliché, hindsight is not 20/20; it is barely better than legally blind. If you don’t record and track your forecasts, you shouldn’t say that you knew all along what would happen in the end. And if you can’t review all predictions of pundits, you should never believe that they foresaw the future.”

And that is something worth remembering.

The column originally appeared on the Vivek Kaul Diary on March 29, 2016