Vivek Kaul

Life is a great leveller. The Russians thought they had found an easy way to launder money by simply moving it to banks in Cyprus.

The Cyprian banks thought they had found an easy way to make more money on that money by investing it in Greece.

Trouble started once the Greeks decided that the borrowed money was as good as their own, and did not have to be returned. This left the Cyprian banks reeling with big holes in their balance sheets.

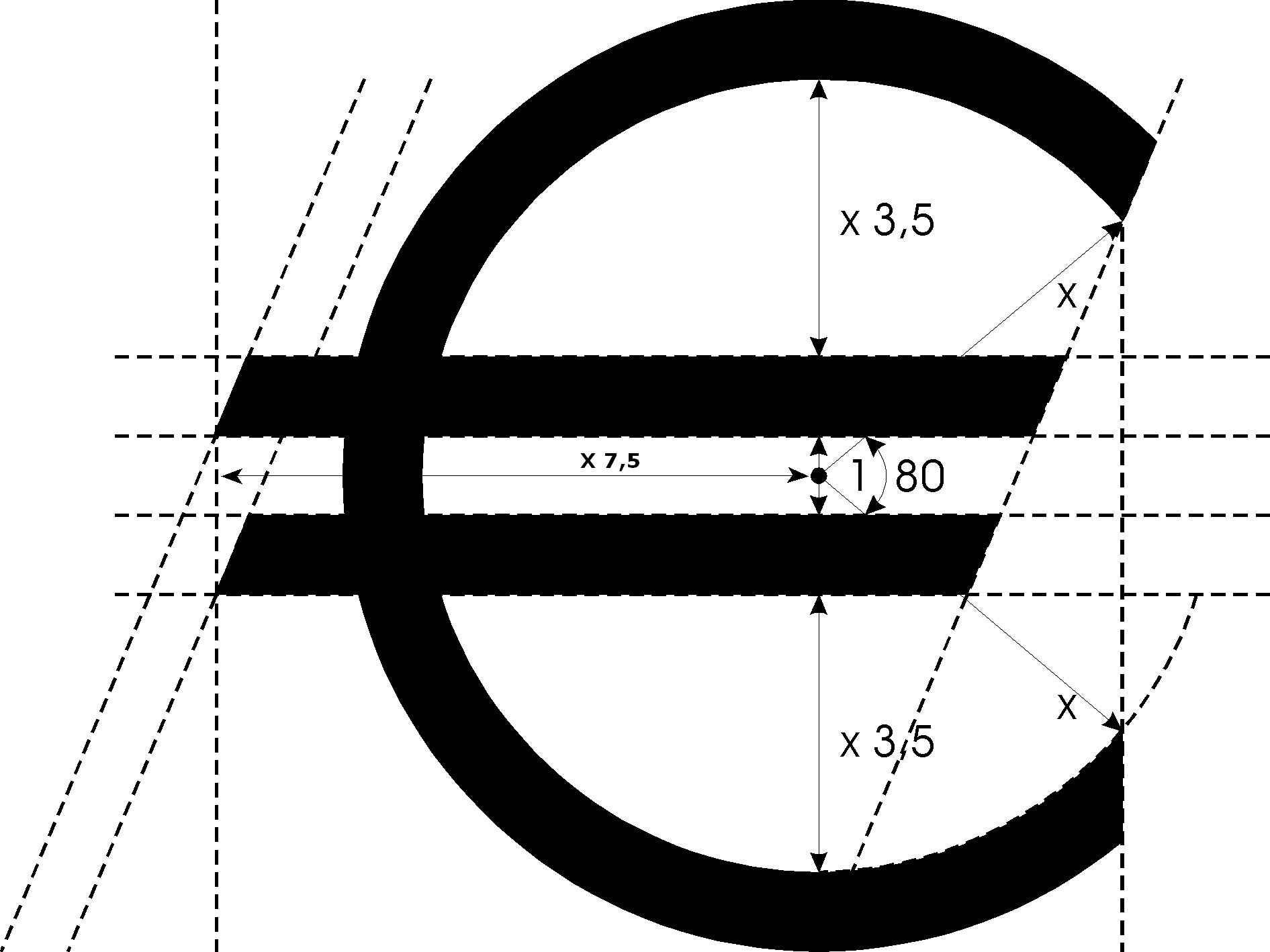

The Cyprian banks were too big to be rescued by the Cyprian government. Hence, they needed to be bailed out by an institution which was bigger than the Cyprian government. The International Monetary Fund(IMF) and the European Union(EU) moved in together and agreed to handover € 10 billion (or around $13billion) to the Cyprian government.

But there was the risk of the Cyprian government also deciding to behave like the Greeks had before them, and treat the € 10 billion bailout as their own money. So, the IMF and the EU demanded some sacrifices to be made by Cyprus as well.

A plan was made to forfeit a part of the deposits lying in Cyprian banks. A levy of 6.75% was proposed on deposits of less than €100,000 and 9.9% on deposits above that. Of course this did not go down well with the people of the country and they protested. So did its Parliament.

The plan was modified. And it was decided that the government will seize deposits greater than €100,000 lying in the Popular Bank of Cyprus (better known as Laiki Bank), the second largest bank in the country.

This move was accepted by Cyprus because deposits greater than €100,000 were largely held by the Russians. As The Huffington Post wrote “The country of about 800,000 people has a banking sector eight times larger than its gross domestic product, with nearly a third of the roughly 68 billion euros in the country’s banks believed to be held by Russians.” Hence, the move of seizing deposits greater than €100,000 did not impact citizens of Cyprus in a direct way. It ended up screwing the Russians. As I said at the beginning life is a great leveller.

But that does not mean that Cyprus would not have to bear any cost of such a move. Cyprus had positioned itself as a tax haven, to attract money from all over the world. And with the government moving to seize deposits greater than €100,000, it has lost its core industry of banking. Russians and other investors across the world who used Cyprian banks to launder money, will think twice before moving any money into the country. They will also move out the money they have in the country, once the capital controls are relaxed. As Ambrose Evans-Pritchard writes in The Telegraph “The country has just lost its core industry, a banking system with assets equal to eight times GDP, and has little to replace it with.”

What this means is that with its core industry gone, its economy is bound to slowdown in the days to come. The financial sector makes up for around 18% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). “I wouldn’t be surprised to see a 20% all in real GDP,” Noble Prize winning economist Paul Krugman told Pritchard.

There are other estimates of the Cyprian economy slowdown which are equally scary. As Matthew O’ Brien writes in The Atlantic “the International Institute of Finance thinks Cypriot real GDP could fall as much as 20 % over the next few years…And remember, unemployment is already 14.7% n Cyprus. It could easily climb to 25%.”

To cut a long story short, Cyprus is going to be in a much bad shape than it was in the past. So what is the way out for the country? It needs something to replace its banking and financial sector. The manufacturing sector forms just 7% of its GDP.

Tourism is the other big employer in Cyprus. But since Cyprus moved onto the euro as its currency, on January 1, 2008, tourism has become very expensive. “Cyprus cannot hope to claw its way back to viability with a tourist boom because EMU(Economic and monetary union of the European union) membership has made it shockingly expensive. Turkey, Croatia or Egypt are all much cheaper….The IMF says the labour cost index has risen even faster than in Greece, Spain or Italy since the late 1990s,” writes Pritchard.

In the past countries which end up in such a mess have devalued their currency and exported their way out of trouble. When a country devalues its currency its exports become more competitive. Let me explain this in an Indian context. Let us say an Indian exporter exports a certain good at a price of $100 per unit. When one dollar is worth Rs 50, he gets Rs 5000 per unit. Lets say the value of the rupee against the dollar falls to Rs 60 per dollar. In this case the exporter gets Rs 6000 per unit. So with the value of the rupee falling against the dollar an exporter makes more money.

What the exporter can also do is cut his price in dollar terms. If he cuts his price to $90, he will end up with Rs 5400 ($90 x 60), which is greater than the Rs 5000 he was making in the past. At a lower price, his goods will become more competitive in the international market and thus he will be able to sell more.

Iceland is a very good example of the same. A country of 300,000 people which went financially bust a few years back has been able to get its exports going at some level because its currency the Icelandic Krona, fell in value against the other currencies. “What saved Iceland from mass unemployment after its banks blew up – was a currency devaluation that brought industries back from the dead. Iceland’s krona has fallen low enough to make it worthwhile growing tomatoes for sale in greenhouses near the Arctic Circle,” writes Pritchard.

As The Washington Post reports “Iceland experienced a banking collapse in 2008 during which its currency fell in half, from 60 krona to the dollar to 120. It was a horrible series of events for Iceland, but the collapse in the krona also led to surge in exports and tourism that kept unemployment contained.”

But Cyprus cannot do that given that it does not have a currency of its own. It is a part of a monetary union and euro is used as a currency by sixteen other nations . Cyprus can only devalue its way out of trouble if it chooses to move out of the euro and go back to the Cyprian pound which was its currency before it decided to move to the euro.

As O’Brien puts it “The euro isn’t terribly popular in Cyprus right now. Only 48 % of Cypriots were in favour of the common currency last November…compared to 67 % of Irish, 65 % of Greeks, 63 % of Spaniards, and 57 % of Italians. The euro is actually less popular in Cyprus than anywhere else in the euro zone — and it’s only going to get less so as their economy disintegrates.”

It makes great sense for Cyprus to leave the euro in the hope of getting its export going. Moving back to the Cyprian pound will also get its tourism sector up and running again. Let me explain this by extending the example used above. A tourist looking to visit India is more likely to come when one dollar is worth Rs 60, than when its worth Rs 50. At Rs 60 to a dollar, the tourist can consume goods and services worth Rs 6000 in India, whereas at Rs 50 to a dollar his consumption will be limited to Rs 5000. The same logic works for Cyprus as well if the country decides to leave the euro and move back to the Cyprian pound and devalue the pound against the international currencies.

One fear that has constantly been raised about leaving the euro is the fact that once people find out that there is a threat of a country is leaving the euro and moving on to its own currency, they will rapidly pull out money from the country. This argument works to some extent. In case of Cyprus though, international investors who have put their money in the country will pull out (and have already pulled out) their money irrespective of the fact whether the country remains on the euro or not. As O’ Brien puts it “Countries can’t leave the euro because its banks would collapse and there would be massive capital flight, and … wait. These things have already happened in Cyprus. Its banks just got restructured, and it just instituted capital controls. There’s not much left to lose from euro-exit. And plenty to gain.”

The danger of Cyprian citizens moving out their savings is not very strong. As Albert Edwards of Societe Generale writes in his recent report titled The eurozone is working just fine

…as far as Germany is concerned “I know from first-hand experience the extreme difficulty for a European citizen to open an account in another European country it is nigh on impossible for the man in the street.” Given this its highly unlikely that people of Cyprus will be able to move their money out of the country. But that is no guarantee that money will continue to remain in Cyprian banks. As Edwards put it, people have the “choice of stuffing” their “money under the mattress or buying safe financial assets (maybe overseas mutual funds or gold?), or indeed spending the money on goods and services.” (For a more detailed argument on how a country should move out of the euro in a somewhat orderly manner click here).

The country has no plans of leaving the euro currently. Nicos Anastasiades , the President of Cyprus said on March 29, 2013 that “We have no intention of leaving the euro…In no way will we experiment with the future of our country.”

If Cyprus does decide to leave the euro that might encourage other countries to do so as well. There are several countries which could face a Cyprus type of bailout in the days to come. As Guy Verhoftstadt, a former prime minister of Belgium writes in The New York Times “Perhaps Malta, which has an even bigger banking sector than Cyprus relative to G.D.P., much of it highly reliant on offshore depositors. Or maybe Latvia, fast becoming the destination of choice for Russian funds flowing out of Cyprus and now on course to join the euro zone. Even Spain or Italy could be vulnerable to a similar bailout, now that the Dutch finance minister, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, who is president of the Euro Group of finance ministers, has hinted that Cyprus could provide a model for the resolution of future banking crises.”

Given this, the future of the euro looks very dicey. As Martin Wolf, one of the foremost economic commentators of the world, wrote in a recent column in the Financial Times “Old fears that the euro would undermine European unity rather than strengthen it seem more plausible.” Nobody could have put it better.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Cyprus

Cyprus’ financial repression: when people bail out govts

Vivek Kaul

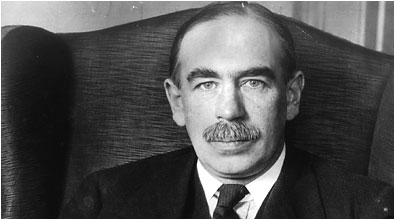

John Maynard Keynes (pictured above) was a rare economist whose books sold well even among the common public. The only exception to this was his magnum opus, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, which was published towards the end of 1936.

In this book Keynes discussed the paradox of thrift or saving. What Keynes said was that when it comes to thrift or saving, the economics of the individual differed from the economics of the system as a whole. An individual saving more by cutting down on expenditure made tremendous sense. But when a society as a whole starts to save more then there is a problem. This is primarily because what is expenditure for one person is income for someone else. Hence when expenditures start to go down, incomes start to go down, which leads to a further reduction in expenditure and so the cycle continues. In this way the aggregate demand of a society as a whole falls which slows down economic growth.

This Keynes felt went a long way in explaining the real cause behind The Great Depression which started sometime in 1929. After the stock market crash in late October 1929, people’s perception of the future changed and this led them to cutting down on their expenditure, which slowed down different economies all over the world.

As per Keynes, the way out of this situation was for someone to spend more. The best way out was the government spending more money, and becoming the “spender of the last resort”. Also it did not matter if the government ended up running a fiscal deficit doing so. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what the government earns and what it spends.

What Keynes said in the General Theory was largely ignored initially. Gradually what Keynes had suggested started playing out on its own in different parts of the world.

Adolf Hitler had put 100,000 construction workers for the construction of Autobahn, a nationally coordinated motorway system in Germany, which was supposed to have no speed limits. Hitler first came to power in 1934. By 1936, the Germany economy was chugging along nicely having recovered from the devastating slump and unemployment. Italy and Japan had also worked along similar lines.

Very soon Britain would end up doing what Keynes had been recommending. The rise of Hitler led to a situation where Britain had to build massive defence capabilities in a very short period of time. The Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was in no position to raise taxes to finance the defence expenditure. What he did was instead borrow money from the public and by the time the Second World War started in 1939, the British fiscal deficit was already projected to be around £1billion or around 25% of the national income. The deficit spending which started to happen even before the Second World War started led to the British economy booming.

This evidence left very little doubt in the minds of politicians, budding economists and people around the world that the economy worked like Keynes said it did. Keynesianism became the economic philosophy of the world.

Lest we come to the conclusion that Keynes was an advocate of government’s running fiscal deficits all the time, it needs to be clarified that his stated position was far from that. What Keynes believed in was that on an average the government budget should be balanced. This meant that during years of prosperity the governments should run budget surpluses. But when the environment was recessionary and things were not looking good, governments should spend more than what they earn and even run a fiscal deficit.

The politicians over the decades just took one part of Keynes’ argument and ran with it. The belief in running deficits in bad times became permanently etched in their minds. In the meanwhile they forgot that Keynes had also wanted them to run surpluses during good times. So they ran deficits even in good times. The expenditure of the government was always more than its income.

Thus, governments all over the world have run fiscal deficits over the years. This has been largely financed by borrowing money. With all this borrowing governments, at least in the developed world, have ended up with huge debts to repay. What has added to the trouble is the financial crisis which started in late 2008. In the aftermath of the crisis, governments have gone back to Keynes and increased their expenditure considerably in the hope of reviving their moribund economies.

In fact the increase in expenditure has been so huge that its not been possible to meet all of it through borrowing money. So several governments have got their respective central banks to buy the bonds they issue in order to finance their fiscal deficit. Central banks buy these bonds by simply printing money.

All this money printing has led to the Federal Reserve of United States expanding its balance sheet by 220% since early 2008. The Bank of England has done even better at 350%. The European Central Bank(ECB) has expanded its balance sheet by around 98%. The ECB is the central bank of the seventeen countries which use the euro as their currency. Countries using the euro as their currency are in total referred to as the euro zone.

The ECB and the euro zone have been rather subdued in their money printing operations. In fact, when one of the member countries Cyprus was given a bailout of € 10 billion (or around $13billion), a couple of days back, it was asked to partly finance the deal by seizing deposits of over €100,000 in its second largest bank, the Laiki Bank. This move is expected to generate €4.2 billion. The remaining money is expected to come from privatisation and tax increases, over a period of time.

It would have been simpler to just print and handover the money to Cyprus, rather than seizing deposits and creating insecurities in the minds of depositors all over the Euro Zone.

Spain, another member of the Euro Zone, seems to be working along similar lines. Loans given to real estate developers and construction companies by Spanish banks amount to nearly $700 billion, or nearly 50 percent of the Spain’s current GDP of nearly $1.4 trillion. With homes lying unsold developers are in no position to repay. And hence Spanish banks are in big trouble.

The government is not bailing out the Spanish banks totally by handing them freshly printed money or by pumping in borrowed money, as has been the case globally, over the last few years. It has asked the shareholders and bondholders of the five nationalised banks in the country, to share the cost of restructuring.

The modus operandi being resorted to in Cyprus and Spain can be termed as an extreme form of financial repression. Russell Napier, a consultant with CLSA, defines this term as “There is a thing called financial repression which is effectively forcing people to lend money to the…government.” In case of Cyprus and Spain the government has simply decided to seize the money from the depositors/shareholders/bondholders in order to fund itself. If the government had not done so, it would have had to borrow more money and increase its already burgeoning level of debt.

In effect the citizens of these countries are bailing out the governments. In case of Cyprus this may not be totally true, given that it is widely held that a significant portion of deposit holders with more than €100,000 in the Cyprian bank accounts are held by Russians laundering their black money.

But the broader point is that governments in the Euro Zone are coming around to the idea of financial repression where citizens of these countries will effectively bailout their troubled governments and banks.

Financing expenditure by money printing which has been the trend in other parts of the world hasn’t caught on as much in continental Europe. There are historical reasons for the same which go back to Germany and the way it was in the aftermath of the First World War.

The government was printing huge amounts of money to meet its expenditure. And this in turn led to very high inflation or hyperinflation as it is called, as this new money chased the same amount of goods and services. A kilo of butter cost ended up costing 250 billion marks and a kilo of bacon 180 billion marks. Interest rates as high as 22% per day were deemed to be legally fair.

Inflation in Germany at its peak touched a 1000 million %. This led to people losing faith in the politicians of the day, which in turn led to the rise of Adolf Hitler, the Second World War and the division of Germany.

Due to this historical reason, Germany has never come around to the idea of printing money to finance expenditure. And this to some extent has kept the total Euro Zone in control(given that Germany is the biggest economy in the zone) when it comes to printing money at the same rate as other governments in the world are. It has also led to the current policy of financial repression where the savings of the citizens of the country are forcefully being used to finance its government and rescue its banks.

The question is will the United States get around to the idea of financial repression and force its citizens to finance the government by either forcing them to buy bonds issued by the government or by simply seizing their savings, as is happening in Europe.

Currently the United States seems happy printing money to meet its expenditure. The trouble with printing too much money is that one day it does lead to inflation as more and more money chases the same number of goods, leading to higher prices. But that inflation is still to be seen.

As Nicholas NassimTaleb puts it in Anti Fragile “central banks can print money; they print print and print with no effect (and claim the “safety” of such a measure), then, “unexpectedly,” the printing causes a jump in inflation.”

It is when this inflation appears that the United States is likely to resort to financial repression and force its citizens to fund the government. As Russell Napier of CLSA told this writer in an interview “I am sure that if the Federal Reserve sees inflation climbing to anywhere near 10% it would go to the government and say that we cannot continue to print money to buy these treasuries and we need to force financial institutions and people to buy these treasuries.” Treasuries are the bonds that the American government sells to finance its fiscal deficit.

“May you live in interesting times,” goes the old Chinese curse. These surely are interesting times.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on March 27,2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Question after Cyprus: Will govts loot depositors again?

Vivek Kaul

So why is the world worried about the Cyprus? A country of less than a million people, which accounts for just 0.2% of the euro zone economy. Euro Zone is a term used in reference to the seventeen countries that have adopted the euro as their currency.

The answer lies in the fact that what is happening in Cyprus might just play itself out in other parts of continental Europe, sooner rather than later. Allow me to explain.

Cyprus has been given a bailout amounting to € 10 billion (or around $13billion) by the International Monetary Fund and the European Union. As The New York Times reports “The money is supposed to help the country cope with the severe recession by financing government programs and refinancing debt held by private investors.”

Hence, a part of the bailout money will be used to repay government debt that is maturing. Governments all over the world typically spend more than they earn. The difference is made up for by borrowing. The Cyprian government has been no different on this account. An estimate made by Satyajit Das, a derivatives expert and the author of Extreme Money, in a note titled The Cyprus File suggests that the country might require around €7-8billion “for general government operations including debt servicing”.

But there is a twist in this tale. In return for the bailout IMF and the European Union want Cyprus to make its share of sacrifice as well. The Popular Bank of Cyprus (better known as the Laiki Bank), the second largest bank in the country, will shut down operations. Deposits of up to € 100,000 will be protected. These deposits will be shifted to the Bank of Cyprus, the largest bank in the country.

Deposits greater than € 100,000 will be frozen, seized by the government and used to partly pay for the deal. This move is expected to generate €4.2 billion. The remaining money is expected to come from privatisation and tax increases.

As The Huffington Post writes “The country of about 800,000 people has a banking sector eight times larger than its gross domestic product, with nearly a third of the roughly 68 billion euros in the country’s banks believed to be held by Russians.” Hence, it is widely believed that most deposits of greater than € 100,000 in Cyprian banks are held by Russians. And the move to seize these deposits thus cannot impact the local population.

This move is line with the German belief that any bailout money shouldn’t be rescuing the Russians, who are not a part of the European Union. “Germany wants to prevent any bailout fund flowing to Russian depositors, such as oligarchs or organised criminals who have used Cypriot banks to launder money. Carsten Schneider, a SPD politician, spoke gleefully about burning “Russian black money,”” writes Das.

It need not be said that this move will have a big impact on the Cyprian economy given that the country has evolved into an offshore banking centre over the years. The move to seize deposits will keep foreign money way from Cyprus and thus impact incomes as well as jobs.

The New York Times DealBook writes “Exotix, the brokerage firm, is predicting a 10 percent slump in gross domestic product this year followed by 8 percent next year and a total 23 percent decline before nadir is reached. Using Okun’s Law, which translates every one percentage point fall in G.D.P. (gross domestic product) to half a percentage point increase in unemployment, such a depression would push the unemployment rate up 11.5 percentage points, taking it to about 26 percent.”

But then that is not something that the world at large is worried about. The world at large is worried about the fact “what if”what has happened in Cyprus starts to happen in other parts of Europe?

The modus operandi being resorted to in Cyprus can be termed as an extreme form of financial repression. Russell Napier, a consultant with CLSA, defines this term as “There is a thing called financial repression which is effectively forcing people to lend money to the…government.” In case of Cyprus the government has simply decided to seize the money from the depositors in order to fund itself, albeit under outside pressure.

The question is will this become a model for other parts of the European Union where banks and governments are in trouble. Take the case of Spain, a country which forms 12% of the total GDP of the European Union. Loans given to real estate developers and construction companies by Spanish banks amount to nearly $700 billion, or nearly 50 percent of the Spain’s current GDP of nearly $1.4 trillion. With homes lying unsold developers are in no position to repay. Spain built nearly 30 percent of all the homes in the EU since 2000. The country has as many unsold homes as the United States of America which is many times bigger than Spain.

And Spain’s biggest three banks have assets worth $2.7trillion, which is two times Spain’s GDP. Estimates suggest that troubled Spanish banks are supposed to require anywhere between €75 billion and €100 billion to continue operating. This is many times the size of the crisis in Cyprus which is currently being dealt with.

The fear is “what if” a Cyprus like plan is implemented in Spain, or other countries in Europe, like Greece, Portugal, Ireland or Italy, for that matter, where both governments as well as banks are in trouble. “For Spain, Italy and other troubled euro zone countries, Cyprus is an unnerving example. Individuals and businesses in those countries will probably split up their savings into smaller accounts or move some of their money to another country. If a lot of depositors withdraw cash from the weakest banks in those countries, Europe could have another crisis on its hands,” The New York Times points out.

Given this there can be several repercussions in the future. “The Cyprus package highlights the increasing reluctance of countries like Germany, Finland and the Netherlands to support weaker Euro-Zone members,” writes Das. The German public has never been in great favour of bailing out the weaker countries. But their politicians have been going against this till now simply because they did not want to be seen responsible for the failure of the euro as a currency. Hence, they have cleared bailout packages for countries like Ireland, Greece etc in the past. Nevertheless that may not continue to happen given that Parliamentary elections are due in September later this year. So deposit holders in other countries which are likely to get bailout packages in the future maybe asked to share a part of the burden or even fully finance themselves.

This becomes clear with the statement made by Jeroen Dijsselbloem, the Dutch finance minister who heads the Eurogroup of euro-zone finance ministers “when failing banks need rescuing, euro-zone officials would turn to the bank’s shareholders, bondholders and uninsured depositors to contribute to their recapitalization.”

“He also said that Cyprus was a template for handling the region’s other debt-strapped countries,” reports Reuters. In the Euro Zone deposits above €100,000 are uninsured.

Given this likely possibility, even a hint of financial trouble will lead to people withdrawing their deposits. As Steve Forbes writes in The Forbes “After this, all it will take is just a hint of a financial crisis to send Spaniards, Italians, the French and others scurrying to ATMs and banks to pull out their cash.” Even the most well capitalised bank cannot hold onto a sustained bank run beyond a point.

It could also mean that people would look at parking their money outside the banking system.

“Even in the absence of a disaster individuals and companies will be looking to park at least a portion of their money outside the banking system,” writes Forbes. Does that imply more money flowing into gold, or simply more money under the pillow? That time will tell.

Also this could lead to more rescues and further bailouts in the days to come. As Das writes “If depositors withdraw funds in significant size and capital flight accelerates, then the European Central Bank, national central banks and governments will have intervene, funding affected banks and potentially restricting withdrawals, electronic funds transfers and imposing cross-border capital controls.” And this can’t be a good sign for the world economy.

The question being asked in Cyprus as The Forbes magazine puts it is “if something goes wrong again, what’s stopping the government from dipping back into their deposits?” To deal with this government has closed the banks until Thursday morning, in order to stop people from withdrawing money. Also the two largest banks in the country, the Bank of Cyprus and the Laiki Bank have imposed a daily withdrawal limit of €100 (or $130).

It will be interesting to see how the situation plays out once the banks open. Will depositors make a run for their deposits? Or will they continue to keep their money in banks? That might very well decide how the rest of the Europe behaves in the days to come.

Watch this space.

This article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on March 26, 2013.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)