Vivek Kaul

“So there is yet another inflation piece that I need to write,” he said, in a rather disappointed tone.

“Oh, but didn’t you just write one a few days back,” she replied. “And I was so looking forward to spending the afternoon at Phoenix Mills.”

“Ah. Safes me the trouble,” he said. “And for once I don’t have to eat that fancy, expensive and bland pasta in white sauce, that you make me eat.”

“But how come you need to write something on inflation so soon?” she asked ignoring the pasta jibe. “Didn’t you write one on Friday?”

“Yes I did. But that was a piece around consumer price inflation (CPI). Today the wholesale price inflation number has come out.”

“Oh,” she said. “And how bad is it?”

“The wholesale price inflation(WPI) number for November 2013 came in at 7.52%. In comparison the number was at 7% in October 2013. Interestingly, the WPI number for September 2013 was revised to 7.05%, from the earlier 6.46%.”

“And what does that tell us?”

“What that tells us is that the WPI numbers after September are also likely to be revised upwards,”he said.

“Hmmm. So inflation might be more than what we are being told right now?”

“Yes. Also, the food inflation was at 19.93%. Within it, onion prices rose by 190.3% and vegetable prices rose by 95.3$. Interestingly, the onion prices have fallen by 5.1% between October and November 2013. But potato prices have risen by 30.8% in the same period.”

“Yeah. I bought both onions and potatoes recently and realised that.”

“But food inflation at nearly 20% is what is making the scenario difficult for most people. Half of the expenditure of an average Indian household in India is on food. In case of the poor it is 60%. Over the last few years the government has gone on a spending spree in rural India, in the hope of tackling poverty. It has led to wages in rural India going up by 15% per year, over the last five years.”

“But isn’t that good?”

“Well, not in an environment where food prices are going up by 20%. You must remember that half of the expenditure of an average Indian family is on food.”

“And that is having other economic repercussions?” she asked.

“Yes. When people spend significantly more money on food, they are likely to cut down on other expenditure. And this also reflects in inflation data.”

“How?”

“Manufactured products form a little under 65% of the wholesale price inflation index. The inflation in case of manufactured products stands at 2.64%. So inflation is primarily being driven by food articles. The other big contributors to inflation have been cooking gas and diesel, which have risen by 10.9% and 15.7% respectively.”

“Oh, is that really the case. I did not know that,” she replied. “But why are the prices of manufactured products not going up as fast as of the food articles and fuel?”

“I think I have already explained that to you.”

“Really?”

“Yes. When people are spending more and more money on buying food. They are likely to be left with less money to buy everything else. In this scenario they are likely to cut down on other expenditure.”

“Other expenditure?”

“It could be anything. From buying consumer durables to cars to everything without which one can do without in the immediate future.”

“And this has an impact on businesses?” she asked.

“Yes. When the demand is not going up, businesses are not in a position to increase prices. And that is reflected in the manufacturing products inflation of just 2.64%. It was at 5.41% in November 2012.”

“Interesting.”

“Yes, what this really means is that business growth is slowing down and this in turn will be reflected in slow economic growth as well.”

“Hmmm. Thanks for explaining this to me.”

“My pleasure.”

“So why don’t you finish writing this and then we will go increase the other expenditure.”

“You mean pasta in white sauce?” he asked.

“Yes. Remember we are doing this for the nation.”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on December 16, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

CPI

November CPI at 11.24: Here is why we have got those inflation blues

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

Hey, Mr. President,

All your congressmen too,

You got me frustrated,

And I don’t know what to do

I’m trying to make a living,

I can’t save a cent,

It takes all of my money,

Just to eat and pay my rent

I got the blues,

Got those inflation blues

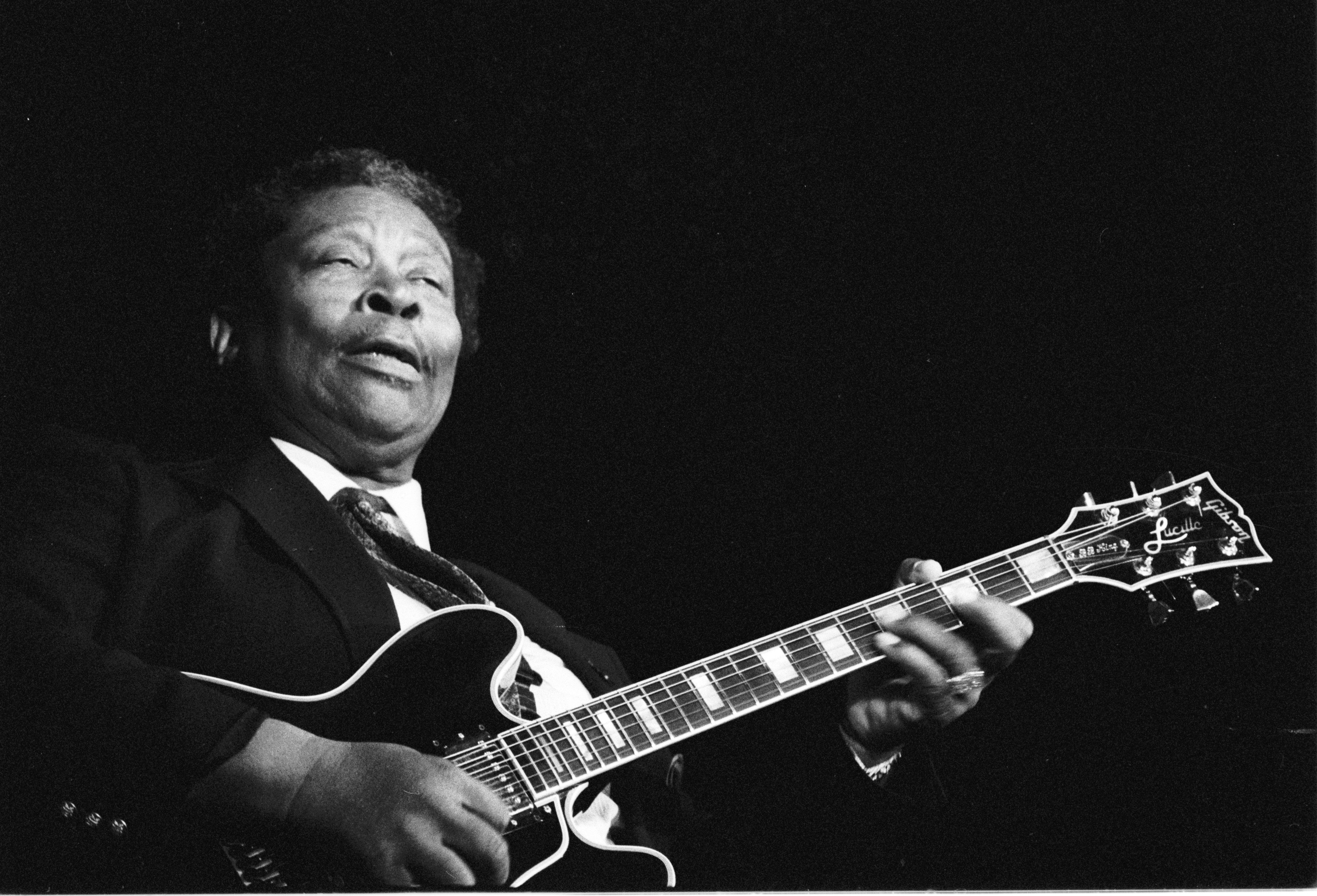

Or so go the lines of a song sung by the American blues musician BB King. (You can hear the complete song here). The United States and other parts of the Western world are currently going through an environment of very low inflation. But India definitely has got what King called the inflation blues.

The consumer price inflation(CPI) for the month of November 2013 was at 11.24%. In comparison the number was at 10.17% in October 2013. Within CPI, the food inflation was at 14.72%. And within food inflation, vegetable prices rose by 61.6% and fruit prices rose by 15%, in comparison to November 2012.

The purchasing power of rupee has gone down. In simple terms, a rupee buys significantly lesser stuff than it did a year back. Or as King put it:

Now you take that paper dollar,

It’s only that in name,

The way that buck has shrunk,

It’s a lowdown dirty shame.

Why has this happened? In the first seven months of the current financial year i.e. the period between April 1, 2013 and October 31, 2013, the government of India spent around 99% more money than it earned. Yes, you read it right. During the period it earned Rs 4,64,123 crore and it spent Rs 9,22,009 crore, which is 98.7% more.

It has followed this practice, where it has spent much more than it has earned, over the last few years. This increase in spending has largely been account of government doles like a higher minimum support price being offered for rice and wheat being sold by farmers to the government.

These doles are being handed out to the citizens of this country, in the hope that they will continue to vote for Congress led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government.

This excessive government spending has not been matched by an increase in production. This means, that an increased amount of money has been chasing a similar number of goods and services and that has led to higher prices i.e. inflation.

The jhollawallahs who think they have their heart in the right place (and everyone else is a bourgeois) have often made the argument that the government is only spending money on the poor. This spending has led to rural wages rising at 15% per year, over the past five years. This is the fastest in Asia.

The trouble is that productivity has not risen at the same rate. Hence, the amount of goods and services being produced have not risen at the same rate as income. This, as explained earlier, has led to more money chasing the same number of goods and services, leading to high inflation.

And this hurts the poor the most. In fact, rural inflation for November 2013, stood at 11.74%, significantly higher than the urban inflation of 10.53%. What is worse is the fact that food inflation is close to 15% and vegetable prices have risen by greater than 60% in the last one year.

As I have often pointed out in the past, half of the expenditure of an average household in India is on food. In case of the poor it is 60% (NSSO 2011). So, inflation hurts the poor the most. If that was not the case, the Congress party wouldn’t have lost the recent state assembly elections so badly. Yes, rural wages have gone up, but the question is whether they have gone up enough to compensate for higher prices?

A higher inflation also leads to the regular expenditure of people as a proportion of income going up. Given this, they need to cut down on expenditure on non essential items like consumer durables, cars etc, in order to ensure that they have enough money in their pockets to pay for food and other essentials. Or as King put it:

And things are going up and up and up and up,

And my cheque remains the same,

That’s why I got the blues,

Got those inflation blues.

This ultimately reflects in the index of industrial production(IIP), a measure of industrial activity. For October 2013, IIP fell by 1.8% in comparison to the same period last year. If people are not buying as many things as they used to, there is no point in businesses producing them. This is reflected in the slowdown in manufacturing which forms 75% of the IIP. It fell by 2% in October 2013.

When we look at IIP from the use based point of view, the production of basic goods, which have most weight, fell by 1.6%. The production of consumer goods and consumer durables fell by 5.1% and 12% respectively.

All this ultimately leads to slower economic growth. Given this, if India needs to get back to the high economic growth rates of the past, it first needs to kill high inflation. But that is easier said than done.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on December 13, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

If only Raghuram Rajan could control onion prices too

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

On November 12, the rupee touched 63.70 to a dollar. On November 13, Raghuram Rajan, the governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) decided to address a press conference. “There has been some turmoil in currency markets in the last few days, but I have no doubt that volatility may come down,” Rajan told newspersons.

Rajan was essentially trying to talk up the market and was successful at it. As I write this, the rupee is quoting at at 63.2 to a dollar. The stock market also reacted positively with the BSE Sensex going up to 20,568.99 points during the course of trading today (i.e. November 14, 2013), up by 374.6 points from yesterday’s close.

But the party did not last long. The wholesale price inflation (WPI) for October 2013 came in at 7%, the highest in this financial year. In September 2013 it was at 6.46%. In August 2013, the WPI was at 6.1%, but has been revised to 7%. The September inflation number is also expected to be revised to a higher number. The stock market promptly fell from the day’s high.

A major reason for the high WPI number is the massive rise in food prices. Overall food prices rose by 18.19% in October 2013, in comparison to the same period last year. Vegetable prices rose by 78.38%, whereas onion prices rose by 278.21%.

Controlling inflation is high on Rajan’s agenda. “Food inflation is still worryingly high,” he had told the press yesterday. In late October, while announcing the second quarter review of the monetary policy Rajan had said “With the more recent upturn of inflation and with inflation expectations remaining elevated… it is important to break the spiral of rising price pressures.”

If Rajan has to control inflation, food inflation needs to be reined in. The trouble is that there is very little that the RBI can do in order to control food inflation.

A lot of vegetable growing is concentrated in a few states. As Neelkanth Mishra and Ravi Shankar of Credit Suisse write in a report titled Agri 101: Fruits & vegetables—Cost inflation dated October 7, 2013, “While the Top 10 vegetable producing states contribute 78% of national production, the contribution of West Bengal, Orissa and Bihar is much higher than their contribution to overall GDP. For example, despite being just 2.7% of India’s land area and 7.5% of population, West Bengal produces 19% of India’s vegetables, dominating the production of potatoes, cauliflowers, aubergines and cabbage. In fact, for almost each crop, the four largest states are 60% or more of overall . In particular, Maharashtra dominates the onion trade (45% of national production by value), while West Bengal produces 38% of India’s potatoes, 49% of India’s cauliflower and 27% of India’s aubergines (brinjal). ”

The same stands true for fruits as well. As the Credit Suisse analysts point out “Maharashtra (MH) dominates citrus fruits (primarily oranges), Tamil Nadu (TN) produces nearly 40% of India’s bananas, Andhra Pradesh (AP) is Top 3 in all the three major fruits, and Uttar Pradesh (UP) produces a fifth of India’s mangoes.”

Hence, the production of vegetables as well as fruits is geographically concentrated. What this means is that if there is any disruption in supply, there is not much that can be done to stop prices from goring up. Given the fact that the production is geographically concentrated, hoarding is also easier. Hence, it is possible for traders of one area to get together, create a cartel and hoard, which is what is happening with onions. (As I argue here). There is nothing that the RBI can do about this. What has also not helped is the fact that the demand for vegetables has grown faster than supply. As Mishra and Shankar write “Supply did respond, as onion and tomato outputs grew the most. But demand rose faster, with prices supported by rising costs.” Hence, even if food inflation moderates, there is very little chance of it falling sharply, feel the analysts.

This is something that Sonal Varma of Nomura Securities agrees with. As she writes in a note dated November 12, 2013 “On inflation, vegetable prices have not corrected as yet and the price spike that started with onions has now spread to other vegetables. Hence, CPI (consumer price inflation) will likely remain in double-digits over the next two months as well.” The consumer price inflation for the month of October was declared a couple of days back and it was at 10.09%.

Half of the expenditure of an average household in India is on food. In case of the poor it is 60% (NSSO 2011). The rise in food prices over the last few years, and the high consumer price inflation, has firmly led people to believe that prices will continue to rise in the days to come. Or as economists put it the inflationary expectations have become firmly anchored. And this is not good for the overall economy.

As Varma puts it “For a sustainable decline in inflation to pre-2008 levels, the vicious link between high food price inflation and elevated inflation expectations has to be broken. The persistence of retail price inflation near double-digits for over five years has firmly anchored inflationary expectations at an elevated level. The role of monetary policy in tackling food price inflation is debateable.”

What she is saying in simple English is that there not much the RBI can do to control food inflation. It can keep raising interest rates but that is unlikely to have much impact on food and vegetable prices.

Varma of Nomura, as well as Mishra and Shankar of Credit Suisse expect food inflation to moderate in the months to come. But even with that inflation will continue to remain high.

As Varma put it in a note released on November 14, “Looking ahead, we expect vegetable prices to further moderate from December, which should lower food inflation. However, this is likely to be offset by other factors. Domestic fuel prices remain suppressed and the release of this suppressed inflation (especially in diesel) will continue to drive fuel prices higher. Also, manufacturer margins remain under pressure and hence the risk of further pass-through of higher input prices to output prices, i.e., higher core WPI inflation, is likely.”

What this means is that increasing fuel prices will lead to higher inflation. Also, as margins of companies come under threat, due to high inflation, they are likely to increases prices, and thus create further inflation.

All this impacts economic growth primarily because in a high inflationary scenario, people have been cutting down on expenditure on non essential items like consumer durables, cars etc, in order to ensure that they have enough money in their pockets to pay for food and other essentials. And people not spending money is bad for economic growth.

If India has to get back to high economic growth, inflation needs to be reined in. As Rajan wrote in the 2008 Report of the Committee on Financial Sector Reforms “The RBI can best serve the cause of growth by focusing on controlling inflation.” The trouble is that there is not much that the RBI can do about it right now.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on November 14, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

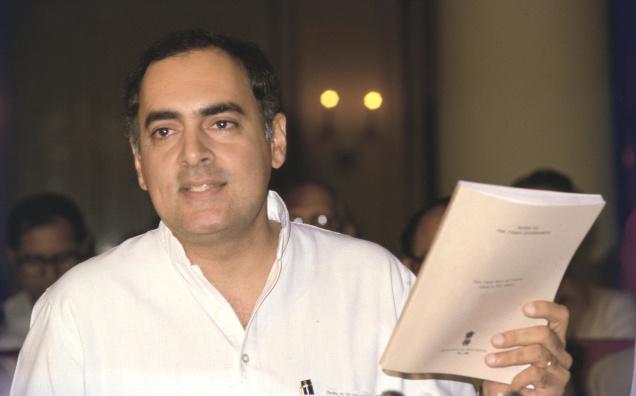

Inflation over 10%: India needs a Rajiv Gandhi Inflation Control Yojana

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

“But Ma I want to become an economist,” said the son.

“An economist?” asked the mother. “Why in the world do you want to do that? You are already a politician.”

“Aren’t they kind of cool?” asked the son.

“Care to explain?”

“Look at Rajan at the Reserve Bank, the women are just swooning over him,” said the son. “Mrs De even wrote a column on how hot he is.”

“Yes. But do you remember the one before Rajan? No woman would have fallen for him, even though he did try and learn the salsa dance,” said the mother, puncturing the bubble.

“Ah, trust you to spoil the fun as always,” said the son. “I was so looking forward to the women swooning over me.”

“Aren’t they already,” replied the mother, trying to do some damage control. “Look at the number of responses we have got to that advertisement we placed on globalshadi.com. Wanted a fair, convent educated, homely girl who respects her elders and can cook.”

“He He.”

“But why do you suddenly want to become an economist?”

“Oh, every other day the media talks about inflation, index of industrial production and what not,” said the son. “And I don’t understand any of it.”

“But you don’t have to understand all that beta,” said the mother. “What else do we have mauni baba for?”

“Oh yeah, mauni baba is an economist, I had almost forgotten, given that he rarely speaks these days.”

“Yes. Let me just call him for you.”

Five minutes later, mauni baba is hurried in through the door.

“What happened madam?” he asked. “Hope all is well.”

“Nothing really,” she replied. “My son here just had a few small doubts. I’ll leave the two of you alone to have a man to man talk.”

Saying this, the mother left the room and the son decided to brush up on his economics.

“You know sir, the index of industrial production(IIP) number came in earlier in the day and it rose by 2%.”

“Yes, it did beta. What do you want to know about it?” asked mauni baba rather lovingly.

“Why is the number so low?”

“We are going through tough times. You know the IIP essentially measures the level of the industrial activity in the country.”

“But isn’t 2% very low?”

“Yes it is. In fact, if we look at just manufacturing which forms 75% of the IIP, it grew by only 0.6%.”

“Oh, so low?”

“Yes,” said mauni baba. “The industrial activity in the country has come to a standstill.”

“But why is that?” asked the son.

“People are not buying as many cars as they were. Neither are they buying consumer durables, which fell by 10% during September 2013, in comparison to the same period last year,” said mauni baba, without answering the question.

“But what is the problem?”

“The problem is inflation. The consumer price inflation for the month of October 2013 was at 10.09%.”

“Oh, yes I saw that on television,” said the son. “They keep going on and on about onion and tomato prices going up. I am so bored of watching that.”

“Yes, you should watch Star World Premiere HD.”

“And if they can’t eat onions and tomatoes, why don’t they try pasta and pizza,” said the son. “Or even caviar.”

“Doesn’t go down well with the Indian taste, you know,” said mauni baba. “We need our dal, rice and rasam.”

“So you were telling me something about inflation.”

“Yes. So inflation is greater than 10%. Food inflation is higher. Consumer price inflation number suggests that food inflation is at 12.56%. As per the wholesale price inflation number, the food inflation is at 18.4%.”

“And what does that mean?”

“Half of the expenditure of an average Indian household goes towards food. Given the rate at which food prices are rising, more and more money is being spent on paying for food and other essentials.”

“Oh.”

“Hence, there is very little money left to buy non essential items like consumer durables and cars. And this leads to low industrial activity. When the demand falls, so does the supply.”

“But where does this inflation come from?” asked the son. “Why can’t we just stop it by launching a RGICLY?”

“RGICLY?” asked mauni baba. “What is that?”

“Rajiv Gandhi Inflation Control Yojana,” explained the son, very seriously.

“We can try, we can try,” said mauni baba going with the flow.

“But where does this inflation come from?”

“Well, over the last few years, the government has increased its expenditure. All this money being spent lands up in the hands of people. And they go out and spend that money. When a greater amount of money chases the same amount of goods and services, prices rise. Food prices particularly work along these lines.”

“Ah. So basically we need to grow more onions and tomatoes.”

“Yes, yes,” said mauni baba. “Its an opportune time to launch IGKTUY.”

“IGKTUY?” asked, the confused son. “What is that?”

“Indira Gandhi Kaandha Tamatar Ugaao Yojana.”

“Kaandha why not just Pyaaz or Pyaaj?” asked the son. “No one understands Kaandha in North India.”

“Oh, I just though IGK comes in a sequence and thus, sounds better,” mauni baba explained.

“IGK or IJK?” asked the son.

“Oh, never mind.”

“But now I get it. Basically inflation is killing growth,” said the son.

“Yes, in fact there is even a term for it.”

“And what is that?”

“Stagflation, which is a combination of stagnation and inflation.”

“Ah, stagflation,” said the son. “I quite like the term. Reminds me of all the stag parties I used to attend.”

“So can I go now?” asked mauni baba.

“Wait, wait, wait,” said the son. “I just understood what you were really trying to say.”

“What?”

“That, mother is essentially responsible for everything. She was the one who got the government to increase its expenditure and spend much more than it earned, which is what finally led to inflation.”

“But I didn’t say that,” mauni baba protested.

“You did not. But that was what you meant,” said a confident son. “Mother won’t like listening to this.”

“Ah. You are making the same mistake as other people.”

“What?”

“They don’t call me mauni baba just for nothing,” said mauni baba and walked out confidently from the room.

The mother soon came back into the room and the son told her everything. As he finished, the mother burst out into a hearty laugh.

“You know, this is quite unbelievable,” she said. “You want me to believe that for the last half an hour mauni baba was speaking and you were listening?”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on November 13, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Dear Beni Prasad, it’s govt, not farmer, who benefits from inflation

Vivek Kaul

“Beni Prasad Verma is not a particularly bright fellow,” said Mohan Guruswamy, Chairman of Centre for Policy Alternatives, a New Delhi based think tank, on Times Now late last night.

The remark was in reference to Beni Prasad Verma’s comment that “dal (pulses), aatta (flour), rice and vegetables have become expensive. The more the prices, the better it is for farmers. I am happy with this inflation…Media says the cost of food has increased, but it is benefiting farmers… and the government is in favour of farmers’ profit.” Verma is the union minister of steel.

There are several logical inconsistencies in what Verma said during the course of the day yesterday. An increase in price and the farmer benefitting from it are two very different things. As we know the farmer does not sell his produce directly to the consumers. His produce goes through a series of middlemen. That being the case it’s the middlemen who buy agriculture produce from the farmers, who might be gaining the most from a rise in price. And not the farmer. This has been the case in the past whenever India has seen a shortage of onions.

But what if the farmer is benefitting from the rise in price? This means that the farmer is actually able to sell his produce at a higher price. Even then Verma’s statement does not make sense.

It does not take into account the fact that a normal farmer does not produce all the goods he consumes. So a rice farmer may not be farming vegetables. And a vegetable farmer may not be producing dal and so on. Hence, a rice farmer might gain when the government announces a higher minimum support price for rice, but he loses out because he also needs to buy dal, vegetables, sugar and so on. And the prices of these food products have also been going up.

The latest inflation number based on the consumer price index was released today. The inflation for the month of July 2012 came in at 9.86%. This means that prices on the whole were up by 9.86% in the month of July 2012 in comparison to July 2011.

The inflation for July 2012 was marginally down from the inflation of 9.93% experienced in the month of June, 2012. Within this the food price inflation stood at 11.53%. The number was at 10.71% in June, 2012.

The point I am trying to make is that farmers other than growing what others eat, also eat what other farmers grow. This is a basic fact that Beni Prasad Verma did not realize while making the statement that he did. And if food prices on a whole went up by 11.53% in July 2012, it surely does not benefit farmers because other than being producers of food products, they are its consumers as well.

Now that’s one part of the argument.

A high inflation also hurts consumers at all levels, which includes farmers. They cut down on their planned spending as prices rise and this in turns hurts businesses and the overall economy. Businesses do not like to spend money on newer projects as consumers cut down on consumption.

So the question is who benefits in an environment when the inflation is high? “The most obvious beneficiary of higher inflation, at least in the short term, is the government. Since…the government will always be able to pay its debt, at least domestically since higher inflation effectively reduces the long-term cost of borrowing money,” writes Kyle Bumpus in an article titled Who Benefits From Inflation? (you can read the whole article here)

Let’s take a look at this statement in the context of India. The return on a ten year government bond as I write this is around 8.22%. The government essentially issues bonds to finance its fiscal deficit or the difference between what it earns and what it spends.

The consumer price inflation for the month of July 2012 has come in at 9.86%. What does this mean? This means that the government can effectively raise money from the market at the rate of 8.22% when inflation is at 9.86%. This effectively means that the real rate of interest is negative (the nominal rate of interest i.e. 8.22% minus the inflation i.e. 9.86%).

Hence the interest that the government offers on its bonds is even lower than the rate of inflation. So technically investors who are buying government bonds are effectively losing money, given that the interest they get paid is lower than the rate of inflation.

The question is why are investors then ready to buy government bonds which pay an interest lower than the prevailing rate of inflation? “So negative real rates may simply indicate that savers are incredibly cautious, and that businesses are reluctant to invest in new projects,” wrote The Economist in a recent edition. “When an economy is growing rapidly, there should be an abundance of profitable investment opportunities. Businesses are happy to borrow at high real rates, confident that they can still earn an even higher return,” it added.

But given the state of the economy right now the businesses and savers would rather buy government bonds and lose a little money on it, rather than invest it anywhere else. This demand for government bonds, allows the government to pay a rate of interest which is lower than the prevailing rate of inflation. In the strictest sense of the term the government gets paid to borrow. Hence, it benefits from inflation.

And not the farmer. This is something that Beni Prasad Verma either does not understand or is simply catering to vote bank politics with the assumption that higher food prices benefit farmers. Its time he heard the only Hindi film song written on inflation from the movie Roti, Kapda Aur Makan, written by Verma Malik, “Baakee Kuch Bacha Toh Mehangayi Maar Gayi”.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 21,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/dear-beni-prasad-its-govt-nor-farmer-who-benefits-from-inflation-424931.html

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])