Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

A few months back I stopped going to the local supermarket. There were two reasons for the same. The first reason was the fact that finding a cab that would drop me home, proved to be a tad difficult on occasions in the evenings. Like the autowallahs of Delhi, the taxiwallahs of Mumbai are also a little finicky, when it comes to small distances (though I must add that this happens only in the evenings in Mumbai, unlike Delhi, where it is a perpetual phenomenon). Given this, I had to walk home on occasions, carrying the stuff that I had bought. And that was not very pleasant.

The second reason was the fact that the amount of choice overwhelmed me. It left me confused on what to buy and what not to buy. Even buying something as simple as biscuits could involve a few minutes of decision making. I figured out that calling up my local banya and getting stuff home delivered was easier.

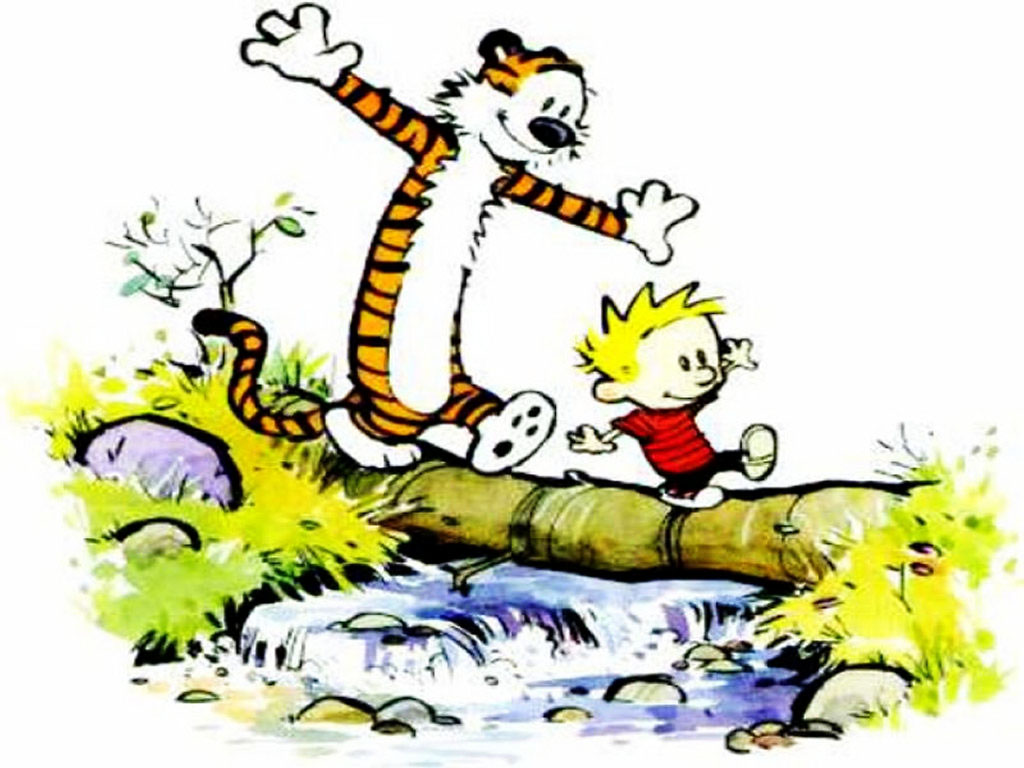

In fact the situation reminded me of a Calvin and Hobbes comic strip that I had read a while back. And this is how the rant from the comic strip goes:

Look at this peanut butter! There must be three sizes of five brands of four consistencies! Who demands this much choice? I know! I’ll quit my job and devote my life to choosing peanut butter! Is “chunky” chunky enough or do I need EXTRA chunky? I’ll compare ingredients! I’ll compare brands! I’ll compare sizes and prices! Maybe I’ll drive around and see what other stores have! So much selection, and so little time.

But this set me thinking on whether I was the only one having problems with more choice or was there something more to it? At a basic level we call love more choice, there is no doubt about that. As Sheena Iyengar writes in The Art of Choosing “Whatever our reservations about choice, we have continued to demand more of it.”

But is more choice helpful? “An abundance of choice doesn’t always benefit us…The expansion of choice has become the explosion of choice, and while there is something beautiful and immensely satisfying about having all this variety at our fingertips, we also find ourselves beset by it,” writes Iyengar.

She says this on the basis of a very interesting experiment on jams, she carried out with Mark R. Lepper . This study was finally published under the title When Choice is Demotivating: Can One Desire Too Much of a Good Thing?

Barry Schwartz summarises this experiment in The Paradox of Choice: Why More is Less, very well. As he writes “Researchers set up a display featuring a line of exotic, high-quality jams, customers who came by could taste samples, and they were given a coupon for a dollar off if they bought a jar. In one condition of the study, 6 varieties of the jam were available for tasting. In another 24 varieties were available. In either case, the entire set of 24 varieties was available for purchase.”

The results were surprising and conclusively proved that choice beyond a point essentially ends up confusing people, rather than making their lives easy, which should be the case. As Schwartz points out “The large array of jams attracted more people to the table rather than the small array, though in both cases people tasted about the same number of jams on average. When it came to buying, however, a huge difference became evident. Thirty percent of the people exposed to the small array of jams actually bought a jar; only 3 percent of those exposed to the large array of jams did so.”

As Iyengar and Lepper conclude in their research paper “. Thus, consumers initially exposed to limited choices proved considerably more likely to purchase the product than consumers who had initially encountered a much larger set of options.”

The logical question to ask is why is that the case? “A large array of options may discourage consumers because it forces an increase in the effort that goes into making a decision. Or if they do, the effort that the decision requires detracts from the enjoyment derived from the results,” writes Scwartz.

In fact, less choice is more beneficial for companies as well. As Iyengar and Lepper point out in their study “Several major manufacturers of a variety of consumer products have have been streamlining the number of options they provide customers. Proctor & Gamble, for example, reduced the number of versions of its popular Head and Shoulders shampoo from 26 to 15, and they, in turn, experienced a 10% increase in sales.”

This does not mean that choice should be done away with completely. The lesson here is that beyond a point choice confuses rather than helping people. When people are given a limited choice they are more likely to make a choice. As Iyengar writes in The Art of Choosing “Since the publication of the jam study, I and other researchers have conducted more experiments on the effects of assortment size. These studies, many of which were designed to replicate real-world choosing contexts, have found fairly consistently that when people are given a moderate number of options (4 to 6) rather than a large number (20 to 30), they are more likely to make a choice, are more confident in their decisions, and are happier with what they choose.”

Interestingly, the rise of the internet was helped to make choosing easier. But it hasn’t. It has introduced one more level of choice. As Schwartz explains “The Internet can give us information that is absolutely up-to-the-minute, but as a resource, it is democratic to a fault—everyone with a computer and an Internet hookup can express their opinion, whether they know anything or not. The avalanche of electronic information we now face is such that in order to solve the problem of choosing from among 200 brands of cereal or 5000 mutual funds, we must first solve the problem of choosing from 10,000 websites offering to make us informed consumers.”

The article originally appeared on www.FirstBiz.com on February 12, 2014

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)