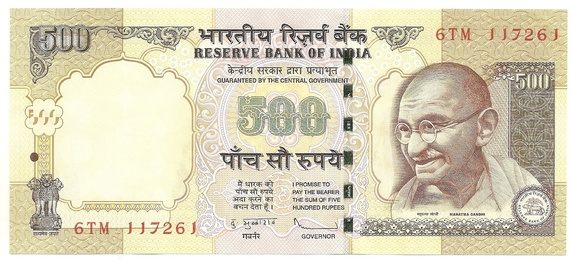

The prime minister Narendra Modi communicated the decision to demonetise Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes to the nation, on the evening of November 8, 2016. The idea was to tackle black money as well as fake notes.

As the government press release accompanying the decision said: “ Use of high denomination notes for storage of unaccounted wealth[black money] has been evident from cash recoveries made by law enforcement agencies from time to time. High denomination notes are known to facilitate generation of black money.”

Between then and now, a lot of analysis has happened on how much black money the government will be able to bring back in the public domain. And once the money is back in the public domain, how much money the government will be able to earn by taxing it.

Many economists and analysts have written research reports on this. These research reports have been turned into WhatsApp forwards which have been widely shared. People have passionately argued on WhatsApp groups, Facebook, Twitter and even in personal communications, as to how successful the demonetisation decision will eventually turn out for the government and in turn, for the nation.

Often big diagrams and flow-charts have been made as to show the thousands of crore that will come into the government kitty, at the end of the day. Any analysis along these lines starts with a basic assumption around the total amount of black money that the Indian financial system has. Black money is the money which has been earned through legal as well as illegal means but on which taxes have not been paid.

As it turns out that the government has no estimation of the total amount of black money in the financial system. This is something that the finance minister Arun Jaitley told the Lok Sabha in a written reply to a question that had been asked by Anant Kumar Hegde, a BJP Lok Sabha MP from Karnataka.

As Jaitley said: “There is no official estimation of the amount of black money either before or after the Government’s decision of 8th November 2016 declaring that bank notes of denominations of the existing series of the value of five hundred rupees and one thousand rupees shall cease to be legal tender with effect from 9th November 2016.”

What does this mean? It basically means that while taking the decision to demonetise Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes, the Modi government did not take into account any estimate of the total amount of black money in the Indian financial system. It further means that the government has no idea of how much money it expects to gain through this entire manoeuvre.

It is amazing that such a huge decision that impacts every citizen of this country was made, even without taking a basic estimate of black money into account. Of course, all big decisions in life, require some leap of faith. The perfect data and the perfect conditions are never there. But at the same time there should be some analytical basis to them as well. There must be some expectations of a payoff for the government that will make it worth all the trouble that the people of India have been be put through.

The surprising thing is that in 2011, the Congress-led UPA government had asked three institutes, the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), the National Institute of Financial Management (NIFM) and the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER), to estimate the total amount of black money in India.

An October 2016 PTI newsreport points out that: “Replying to an RTI query, the Ministry said study reports of NIPFP, NCAER and NIFM were received by the government on December 30, 2013, July 18, 2014 and August 21, 2014 respectively.”

The reports from these institutes have still not been put up in the public domain. “Reports received from these institutes are under examination of the government,” Finance Minister Jaitley had told the Rajya Sabha in May 2015.

Hence, the government has access to three estimates of black money. There must be some explanation behind why it chose not to take any of these reports into account while deciding to demonetise high denomination notes.

In fact, in May 2015, Jaitley had also told the Rajya Sabha: “There is no official estimation regarding the amount of black money generated in the country. Varying estimations of the amount of black money have been reported by different persons/institutions. Such estimations are based upon different sets of facts, data, methods, assumptions, etc. leading to varying inferences. However, sectoral analysis of seizure of valuables and admission of undisclosed income in the searches conducted by the Income Tax Department in the last three financial years indicates that the main sectors in this regard are real estate, trading & manufacturing, contractors, gems & jewellery, services [emphasis added], etc.”

To conclude, the question is how did the government decide to go about to demonetise Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes, and put the citizens of this country through great trouble, without even having a basic estimate of black money in place. On what pretext was such a disruptive decision made? This is a question that Modi and Jaitley need to answer to this nation.

The column originally appeared in Equitymaster on December 19, 2016